Editor’s Note, This interview was conducted over the period of months. Federico and I would ping pong ideas back and forth. Being a busy artist, Clavarino had already moved into several different territories from my principal point of trying to tackle Hereafter, his great opus about power, family, archive and how history is activated through process. Within that framework, our conversation grew and expanded to cover quite a few of his books and projects. To say that Federico is competent would belittle the true value of his intellectual position.

“Let us start with History”.

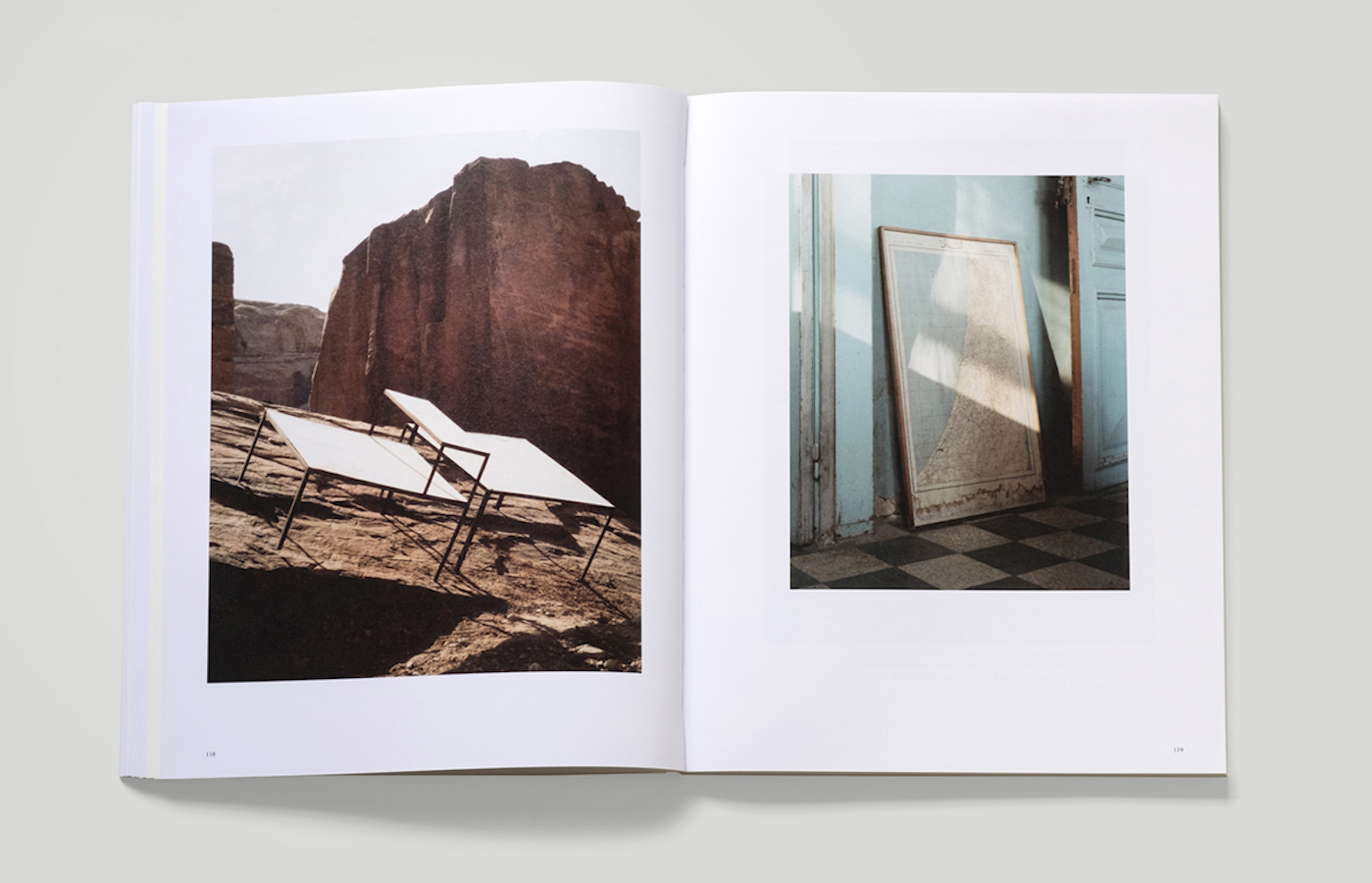

BF: It’s been quite a busy year for you. I know that I am catching you with this interview just before you print a new book, but I wanted to spend a bit of time having a general interview, but also speaking with you about Hereafter (Skinnerboox) and your process in general terms. We met this summer in Poland during a blasted and corrupt heat wave of somewhat epic proportions. It was an albeit too short conversation. I have been gravitating towards your work for some time. I feel that perhaps you are a bit more flexible in terms of process than I had realized. I particularly enjoyed your collaboration “Eel Soup” with Tami Izko during the Fotofestiwal lodz which we both visited and had work in. It was a stark contrast to the book Hereafter, which we were also discussing. The playful physicality of material coupled with the illusory use of mirrors and paralyzed optics formed from the photographs and the sculptural elements felt less enabled by a sense of historical nihilism that I had felt in The Castle for example.

The use of color we had also discussed as being more part of your work than the monochrome as we will see with this book, but also your next offering Alvalade, due out this autumn. On that note of nihilism that I mentioned, perhaps it is too strong of a word and that the elements within your books border on the combative-I feel that somehow in that books that you are at war with symbols, desperate to shatter them, but that you are also looking at these symbols through the course of a European history that is perhaps indicative of the 20th Century, but also possibly knocking on our door again…Do you feel there is a sense of nihilism in some of your work? I would suggest that “elegy” is probably a better word when we discuss Hereafter. In short, are you able to digress a pattern, in reductive terms of course, about the drive that your various bodies of work share or are enabled by? History certainly has be one root element….

FC: It has been a busy year indeed, and there are quite a few things you have mentioned that I feel are worth discussing. One thing is history as a recurring theme, as you have justly pointed out, another one is process, and how it may change from one body of work to another, then there is the Symbolic, i.e. photography’s “textuality” and how I try to work with it and against it. Finally, there is this note of nihilism that you already brought up in Lodz. You are not the first one to do it, so I guess I will have to address such a reading of my work even if I don’t necessarily share it. I will try to go through all of this using Hereafter as my main example, but I am also going to digress into some of the other work and speak more generally about my practice and my ideas.

Let us start with History.

As you suggest, this might be the main drive behind my work. As such, it is also something I find hard to define in general terms, it is more something I am working through, and I believe I am doing so slightly differently in every body of work, I would dare say more and more consciously. Looking at my background, I can see where it comes from: both of my parents studied history, my aunt Elizabeth is a historian, and my brother is very passionate about it too. I also believe class to be a very important factor in the recording of history. Both of my families possessed an exhaustive record of their genealogy because they belonged to the upper classes of their societies for a long time. The abundance of such material, coupled with a progressive loss of privilege and historical prominence, can easily lead to ancestor worship, conservative political views and a general feeling of nostalgia, especially as Europe lapsed into decline in the second half of the XX century. Looking into the past has always been a family thing, but there are ways and ways of doing it, and of investing into it emotionally. It is one thing to sit back and mourn the loss of things like wealth or historical agency, another thing to try to forcefully bring those things back, and quite another to engage in a more complex assessment of the past in order to work towards overcoming present historical contradictions. As someone coming from a mostly conservative family background, I have always had to defend my left-wing views, and at the same time deconstruct the narrative that pervaded family lore. I think this is one of the main forces at work within Hereafter, where it is more evident, but I also think similar mechanisms can be found in Italia o Italia and The Castle. If in Italy I was at odds with the monumental presence of the country’s glorious past and its grotesque re-enactments brought about by fascism and tourism, then in the following book I was trying to deal with the ghosts of Europe by means of a conflation of Totalitarianism and Modernism, in Hereafter the main issue was that of maintaining a tension between elegy and indictment when dealing with narrative material in which family record and colonial epic co-existed.

There is also another thing that runs through all of these works, and this is power.

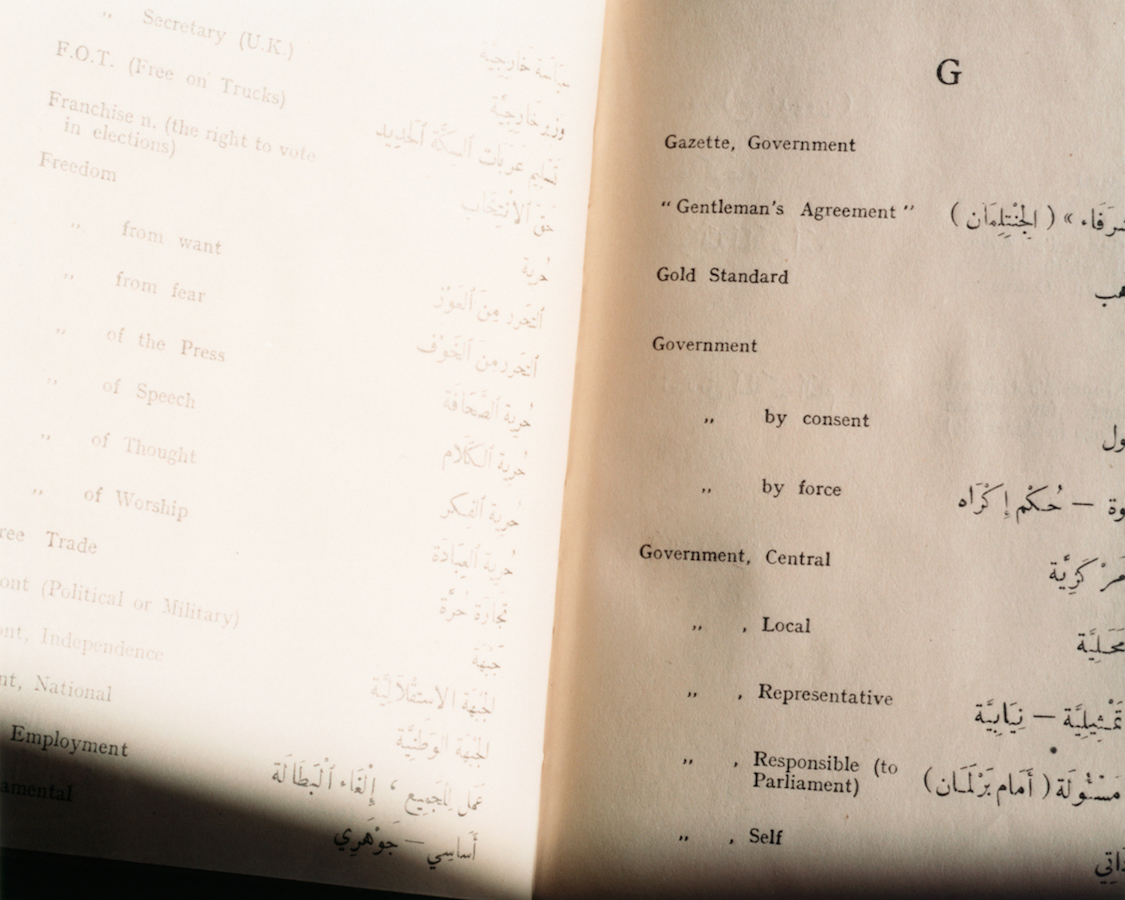

I believe power to be deeply tied to the workings of history, both as one of its driving dialectic forces, and as a constitutive element of the symbolic order that allows for its signification. The metamorphoses of power are the also the transformations in the webs of meaning that we are caught in. Power is what determines us as subjects and it does it through language. I have a fascination for power. It attracts and repels me, and this contradiction is always present in my work. It is there in the ambiguous relationship with form in the two previous works: a love for modernist formal utopias that lives alongside historical trauma and a desire to shatter the symbols of authority. It is a lot more straightforward in Hereafter, as this opposition is dramatised by the figure of my maternal grandfather John. A very authoritative figure, he is the prototype of the imperialist administrator. He is also the locus of a break in communication within the family, the source of an emotional void. At the same time he is the object of an elegy, there is a longing for a missed encounter between him and me as an adult.

“in Hereafter the main issue was that of maintaining a tension between elegy and indictment when dealing with narrative material in which family record and colonial epic co-existed”.

If I look at all three works I can see how I might be struggling with a male figure, a certain kind of subject, who might be roughly defined as the XX century European “fascistic” subject, his self armoured against otherness, defined by his conflictive relationship with both his unconscious and external primitivised forces, caught in between psychology and anthropology. I might have found this subject in my grandfather. He might have been the object of this attraction and repulsion in the first place, but that might just be me making an attempt at some cheap form of psychoanalysis.

The different approaches found in each work might reflect shifts in my struggle with things that I stage in the fields of history and politics but that are also deeply linked with my emotional life, with my private anxieties. I cannot really make myself separate such things. It is in this way that I want to frame the issue of Process.

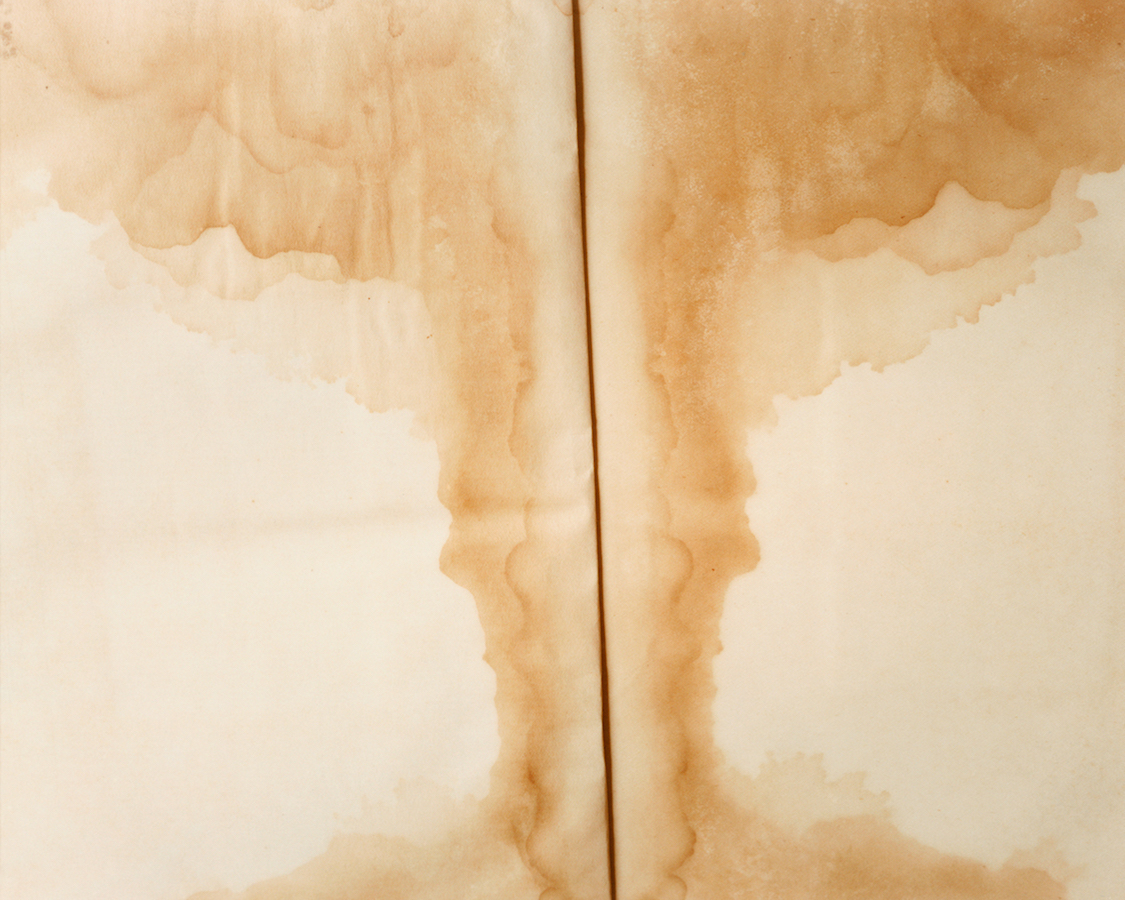

I have noticed that I always start working in response to something happening in my life. It is never a conscious elaboration of a given problem, rather, I need to work through something that presents itself as a powerful yet very vague intuition, something formless, a fever. It’s like a large object sitting in a dark corner, exerting a magnetic impulse on me. It is also similar to what I feel when I experience vertigo: the empty space beckons to me, I feel I want to jump, and at the same time this feeling blocks me. Cameras are the tools I have been using to frame such an emptiness, to play into this dialectic of formlessness and form, or, put in Nietzschean terms, of a Dionysian impulse and an Apollonian harnessing of that potentially destructive force.

Every one of these encounters is part of my own experience, but at the same time it goes beyond me, it exists in history, the unconscious forces at work within me as an individual who experiences a culture are necessarily connected to the forces at work within a broader political unconscious. It is this connection that is complex and tricky. It is also subject to constant change.

My feeling is that I need new tools every time, although some of them remain constant. Walking, for example, has always been part of my practice. It enables me to experience the unexpected as a Flâneur, or its Benjaminian counterpart, the Rag picker, who recovers what was discarded, overlooked or forgotten. It is through a thorough process of editing that I then patch these found fragments together to make sense of them, to map them out in a state of dynamic tension. I work with constellations by mapping out my photographs on large surfaces. Again, there is a contradictory movement that I repeat over time until I feel that the work is finished: a need for openness and randomness followed by an impulse to control and order, in a loop. Hereafter, in this sense, was the largest challenge I have faced up to now: there was an immense amount of material, in the form of existing documents, hours of recorded conversations, and photographs, all of it gathered in the course of three very intense years. The content was heterogeneous, controversial, and very personal. I had to rent a studio just to deal with all of that.

Eel Soup, the work you saw in Łódź, is something rather different. First and foremost it is the collaboration with another artist, and this brought in the elements of her practice into the equation. But I also feel it is a break with the rest of the work, it is something more joyous, more open. I had to relinquish a lot of control. It was also the first time I felt happy about showing work in an exhibition, the rest of my work is more at home in books, while this one is a device that works in space. It creates a space of its own. I am very excited by it, as I am also very excited about collaborations, it makes me feel I can be so many more versions of myself.

This could be a good stone to throw in the face of Nihilism.

“Cameras are the tools I have been using to frame such an emptiness, to play into this dialectic of formlessness and form, or, put in Nietzschean terms, of a Dionysian impulse and an Apollonian harnessing of that potentially destructive force”.

Of course, it would be impossible here to talk exhaustively about what nihilism is in Western culture, and I am ill equipped to do it, but I will try to articulate my understanding of it in order to express what my position is. For how I see it, nihilism is something powerfully present in nineteenth and twentieth century European philosophy. It was central to Nietzsche’s thought, and present in its re-readings by Heidegger and Deleuze. It also takes up different forms: we can speak of a moral nihilism, of an existential nihilism, of an epistemological nihilism, an ontological nihilism and so on. To put it bluntly, it has to do with the denial of things such as the good/evil binary, but also value, meaning, and existence itself. Nietzsche’s view on nihilism is particularly interesting and ambiguous: on the one hand he would condemn a “passive” nihilism that he detected as part of our culture and in the foundations of Christian religion and metaphysics, on the other hand he would call for some sort of “active” nihilism in which oppressive moral values would be overcome by a new mankind capable of existing beyond good and evil and the dissolution of the previous categories of meaning. Seen through this lens, the history of the twentieth century in Europe can be seen as the playing out of a similar “transvaluation of all values” throughout fields as different as politics, economy, and the arts. Its most positive effect has been the unmasking of a lot of positions that seemed fixed. Its most disastrous consequence has been annihilation, in so many different forms.

Baudrillard, for example, speaks about our postmodern condition in terms of fascination: “Fascination (in contrast to seduction, which was attached to appearances, and to dialectical reason, which was attached to meaning) is a nihilistic passion par excellence, it is the passion proper to the mode of disappearance. We are fascinated by all forms of disappearance, of our disappearance. Melancholic and fascinated, such is our general situation”. As a millennial individual prone to melancholia, to a certain extent I identify with such feelings, and I understand how that might come through in my work. Today’s post-truth regime of simulation seems to be where nihilism and capitalist cynical reason have taken us. I believe there is no single answer to all of these problems, and I obviously see myself unfit to suggest a way out of such a predicament, but I do feel that as a general rule, relating to each other in ways that lie beyond the prescriptions of our society’s system could be a productive way of starting something new, or at least to manage to see things somewhat differently. If I then relate all of this back to my practice, that means, among other things, various forms of collaboration.

BF: This is an incredible amount of dialogue/nuanced answer to think through and I thank you for exploring the road to or perhaps from nihilism with me. I think historically speaking, to cover nihilism, or appreciate or at least pay attention to its contrivances and its status as bourgeois tool for the distribution of morality/hierarchy is a great jumping point and though if we look at this history, the history of ideas, I think it would also be important to think through the object-oriented possibility of nihilism within a particular object- be it archive (fever) or other with a particular locus of formality that may govern a reaction such as my own. Without the symbolism you speak of, it would be harder to distort this notion into a malleable conversation.

What I propose to you regarding The Castle and perhaps Italia O Italia is that the nihilism I see in the work functions as an ambassador to the historical ontology , the weight of historical being that you have spoken about as an author-the site lines of physical, if arcane structures enabling the philosophical underpinnings or gravity of your images. Being able to wander, effectively through the morass of civilization’s remnants almost as a strange purveyor of ruin porn, but in doing so being able to fashion a dialectical conversation regarding the image-object that you decide to “record” with your camera. This is of course, in regards to authorship clearly defined in your answer above as to the political economy of your family tree and the nihilistic penchant for watching decay, even if in family mythologies. There is a certain fundament of wonder and fascination that I see in your work and has now been exemplified by the tradition of walking that you speak of-European walking for certain. I think my decidedly anti-virtuous imposition of nihilism on your work stems from the Emanuel Severino and Nietzschean version of it, which abhors the moral plight-the argumentative folly between Christian dogma and the right for (my thoughts imposed) for an object or image to condition its right to existence and its right to declare this position as mutable though time and developing histories, but also to render such an attempt within the larger notions of an event, history and the elasticity of the sacred or its inverse as valid. I would rather speculate as to the chaos of nihilism as it relates to object-hood, but also how we cross-purpose an object’s representation with our seething position as author. We have not even spoken of light lest we wonder flatly into a dialogue with mysticism that I believe concerned Luigi Ghirri and Vilhelm Flusser-the pact of which is to speak, but never to name. So, I am rambling a bit as such.

I want to ask you though in regards to “the historical” which factors in your work, perhaps de facto, are you not (the nihilist spake) intolerant of historical bribery? The imposition (again) of delineated truth to push your will to past truths into an image? We share some common ground here with the discussion of history and my question is perhaps more of a personal inquiry into myself through your work-I find the whole historical mode for understanding what we are drawn to and what we want to speculate upon conditioned too closely to our condition as author-namely for example seeing fascism in Italian Architecture, the stylized and often light accommodating method building quasi-mystic temples such as the (ahem) Mystic Temple in Palermo as an act, when perpetrated upon visually by our cameras as an inherent act of defiance perhaps, but adversely, we could also assert that the object’s will to be recorded is in itself a heretical monumentilization of said history, no matter the position we believe we rally against. Can we make images of terrible things without perpetuating and ultimately preserving their arrogance as object of projected ideological formation? If so, perhaps the valid question then is “What shall we do with history”? Can we trust its intentions?

FC: I would be tempted to turn your last question around here: “What shall History do with us?”

I do believe, with Fredric Jameson, that historical processes are far from being reducible to the accounts we might make of them. There is something like a historical Real. At the same time this is accessible to us only through our constant re-textualisations, and these are inseparable from the ideological horizon of the epoch they belong to. History exists beyond language and ideology, but it is unknowable to us without them. Nevertheless, these cannot be wrenched apart from their historical context, hence the Jamesonian motto: “always historicize!”

When you asked whether we could make images of terrible things without perpetuating the ideologies that caused them, your question made me think about Freud and his idea of a “compulsion to repeat”, according to which a past situation is acted out unconsciously and repetitively instead of being remembered. In this sense, it is by tracing things back to the past that we free the present from being a site of continuous repetition. That is somewhat similar to my idea of historical work: we need to revisit the sites of trauma in order to consign them to the past, which paradoxically means to remember things, and not to forget them.

On the other hand, simply producing images of things is not enough. Technical images such as photographs can quote rather freely from reality, they can extract things out of their context and present them as a series of emptied-out stylisations. In order for them to be productive we must do something to them. One option is to insert them in a field of dynamic tensions that will put their meanings back into motion. I’ll try to elaborate a bit more on this. Images are endowed with a complex temporality, similar in a way to that of memory. As Walter Benjamin wrote, in images “what has been comes together with the now to form a constellation”. What’s more, genuine images for Benjamin are always dialectical, they are the site of the sudden emergence of a tension between two terms that overcome their apparent opposition. Such images become tools to counteract accepted modes of perception and cognition. I would take this definition of image not to define single images as much as networks of them. In this sense, individual photographs, for example, could work as the raw material for the construction of images, which would spring forth in the mind by way of their association. This is in a way similar to Didi-Huberman’s idea of montage, and of his reading of Aby Warburg’s Atlas Mnemosyne as an iconology that “works by disassembly of the figurative continuum, by shots of disjointed details, and by the reassembly of this material in original visual rhythms”.

“History exists beyond language and ideology, but it is unknowable to us without them. Nevertheless, these cannot be wrenched apart from their historical context, hence the Jamesonian motto: “always historicize!”

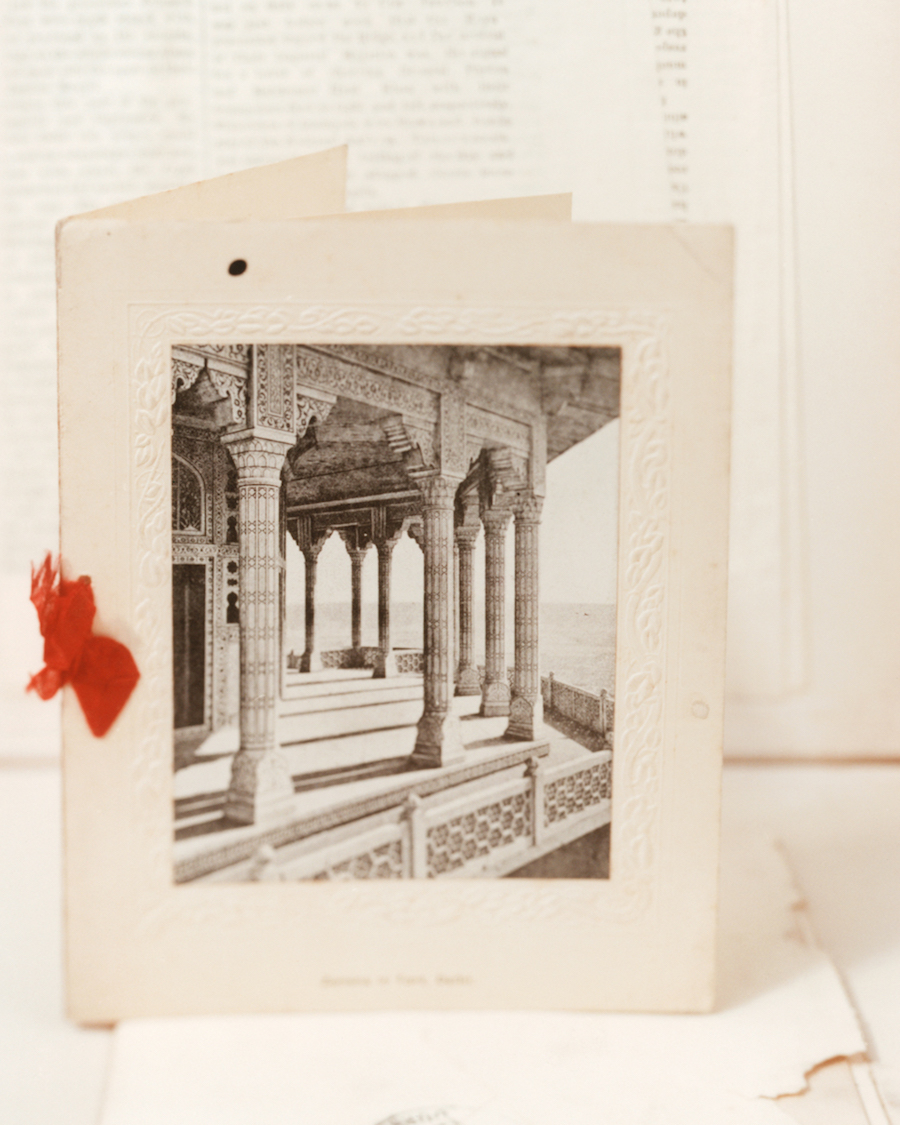

This is what I tried to do in Hereafter. When I decided to revisit the history of my family it was like stepping into a crime scene: something had happened and the only key I had to that thing which had happened were bits and pieces of evidence I had to piece together. In this case it was photographs, letters, drawings, shells, all sorts of other objects, and obviously personal accounts, mostly in the form of anecdotes. This was what I had, and all the rest was not there. In Didi-Huberman’s words, it was “a question of looking at things which are present with an eye to absent things, which, nevertheless, determine, like phantoms, the formers’ genealogy and the very form of their present state”. It is something akin to what happens in detective stories, or in archaeology. The point is that even if I had a lot of material to work with, there still were a lot of unknowns, of amnesia, of emptiness, and the main void at the centre of the story was my grandfather, who had died in 1998. What’s more, the private story of my family was impossible to disentangle from a broader historical account, in this case that of British presence in East Africa and the Middle East. To make a long story short, I was faced with two main narrative lines that were intertwined within the family archive and lore, one of them personal and the other one political, and both of them were haunted by the ghost of Empire. Both were sites of repression: my grandfather was buried without a gravestone, and mechanisms of forgetfulness and denial lie at the heart of Europe’s relationship with its colonial past. There were so many loose threads, and what I tried to do was to piece them together, not by fashioning a continuous account as in so many films, biographies and TV series, but by allowing the discontinuous temporality of the images to play out across the pages of the book, with all of its contradictions and hiatuses. It is precisely in these empty areas that meaning is constructed. These are the openings in which the reader is invited to enter, to dwell and to think.

BF: How does one look at the family history in a forensic matter? That is really interesting. I suspect that the forces of this start with the familiar and in your case have ended in the examination of colonial history as you have mentioned. I found Hereafter super successful in the way in which your aesthetic blended with historical documents etc. That is such a rare pursuit. As someone who works with historical material and reviews books, I find that 90% of that combination fails as people do not understand the material they are working with, nor the way in which contemporary images interplay both visually and polemically etc.

I want to end this by asking what you are up to presently. Since we began this, You had that incredible body of work Eel Soup with Tami and now you have a new book out. Would you want to give me a heads up on what that’s about? I will of course find a copy this November.

FC: I like to draw parallels between what I do and forensics because of the way both narratives are built retrospectively, and also because that retrospection is rooted in absence. All you have is traces and most of what you are looking for, which is how events unfolded, is not there. I am interested in the narrative potential of such a situation, and on how it can relate to history: more specifically, on how a reading of the present conditions our image of the past. On the other hand, the goal of my work is different from that of a forensic investigation: I am interested in putting history back into motion, and not to crystallize it into an indictment. I am more interested in bringing out contradictions and ambiguities than in exercising some kind of power over truth by means of the technology I use or the kind of knowledge I produce. In a moment characterised by a crisis in historicity that translates into ceaseless formal repetition and pastiche on one side, and the reawakening of dormant totalities on the other, I am interested in disentangling the knots of our past in order to reconnect it to the present in some other, and hopefully meaningful, way. My hope is that there might be unexpected forgotten futures lying hidden in the rubble of history. But this is just the more abstract background thinking, the more concrete instance, what goes on in Hereafter, exists between all this and a more personal need to come to terms with my family’s past.

This last consideration might have something to do with what you mentioned about the aesthetics of the work. That is probably one of the trickiest aspects of Hereafter, and maybe its potential failure. I was baffled to see how two well-known bloggers responded to this particular issue in diametrically opposite ways in their reviews of the book, and this might provide us with an interesting example. According to both critics the found material and my own photographs were at odds with each other. One of them, Jörg Colberg, wrote that he enjoyed my photographs very much, but that the archive work was uninteresting in comparison, and text unpleasant to read. The other one, Colin Pantall, would have suppressed my own photographic work and used only the text alongside the family album pictures. I couldn’t take such a coincidence lightly. While Colberg appears to be interested by my photographic vision, and regards the rest as supplementary (or directly off-putting in the case of the text), Pantall is instead interested in the historical content of the archival material and in how it plays with the more contemporary text, but finds my photographs colder and removed from the narrative. The temptation would be now that of considering this as an example of the age-old “form versus content” argument, or at least of some kind of friction between these two somewhat outmoded concepts.

“I like to draw parallels between what I do and forensics because of the way both narratives are built retrospectively, and also because that retrospection is rooted in absence”.

BF: Sure, but if you follow Colin’s work for example, this becomes more clear as someone who makes work about his own family and its German history. So that is clear, whereas Jörg would certainly, in his interest in the formal images be at odds with the archival if it were not by itself. Knowing both fairly well, I am not surprised by this…

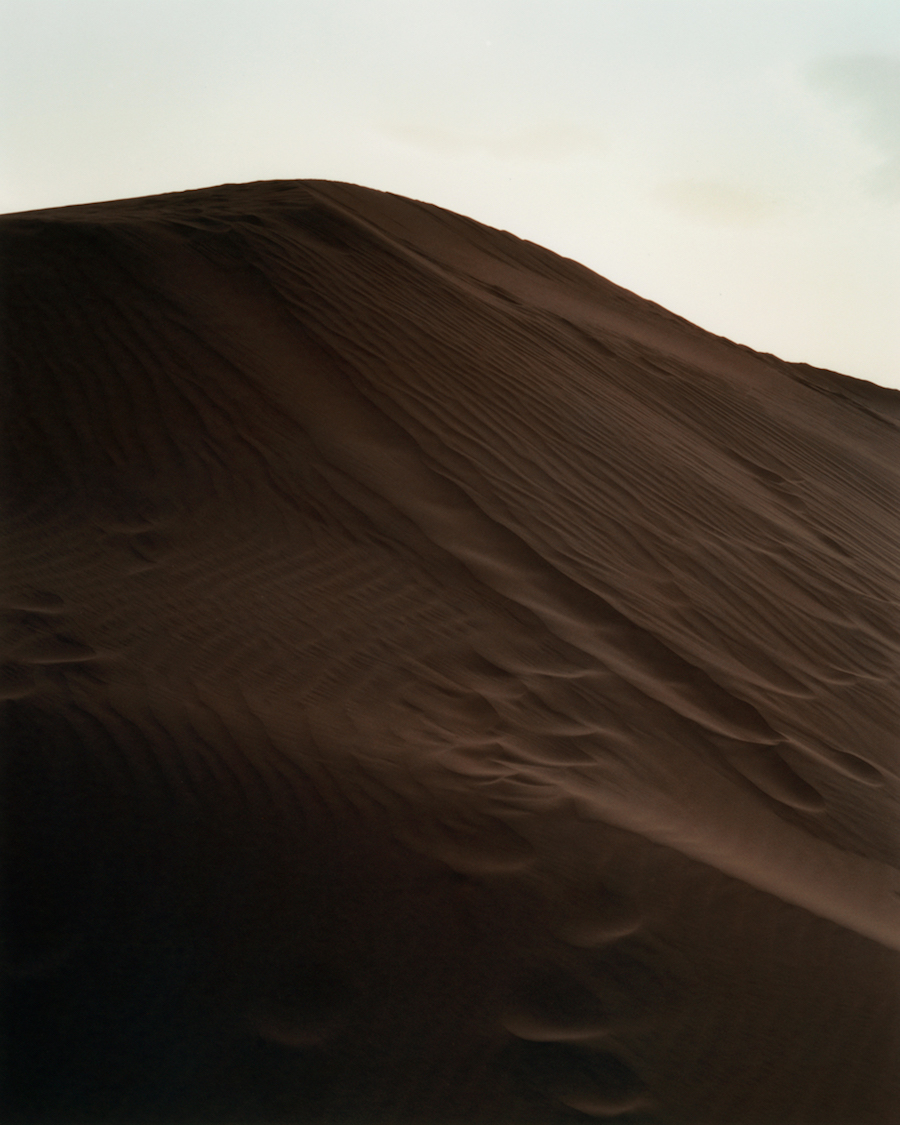

FC: My point here, I guess, is that there is no such thing as a formless content or an empty form, and this is the way the aesthetics of Hereafter are meant to address its subject matter (if I have succeeded in doing so is a wholly different matter). The form of my imagery is meant to echo something present within the archival material, but in doing so, and here is my gamble, it is not meant to be an ironic comment nor a nostalgic re-enactment. Both forms are meant, rather, to enter some kind of productive relationship. I am not interested in addressing my family’s account of its experience from a safe ironic distance, and I cannot do so, for that matter, at least not honestly, as the imagery they produced also produced me. On the other hand, my intellectual honesty and political ideas mean I cannot align myself with the ideological content the form of that imagery implies, which is why am not interested in reproducing it. This is no new dilemma: on the one hand there is no outside position I can occupy, while on the other any inside position seems to be set within a limited and undesirable horizon. This means the only option I am left with is that of failing to occupy either of them, which in this particular case means creating an imagery in which, for example, both a certain “orientalism” and its critique are contained. This doesn’t mean I am trying to get the best of both worlds, but rather to force viewers to adopt an uncomfortable position. I wanted the images to be alluring and troubling at the same time. The viewer, in my hopes and Benedetta Casagrande’s words, is thus “suspended between affection and reflection”.

Within this economy, my own photographs could not exist by themselves without giving up much of their reflexive potential, and the archival images couldn’t exist alone alongside the text without losing much of their affective implications. A more concrete example would be to look at the first chapter of the book. In this case, to disentangle the domestic space of my grandparents’ house from the “imperial phantoms awakened within it” would be to miss the point of the chapter completely, which has to do with the link between that place and the historical processes that made it and that brought those objects (i.e. the “archive”) there. In short, you cannot approach the history of domesticity in Britain without considering its ties with the country’s colonial past, and at the same time you cannot approach colonial ideology without considering the affective spaces it thrived on (as well as those it wrecked, although this is something that lies beyond the scope of my book).

As for the newer work, there is a lot I could say, and the two projects you mention, Eel Soup and Alvalade, are two among many that I am working on. So I will try to write briefly about them by focusing on what they share, and that is an interest I have developed for the body and portraiture. Alvalade is about a neighborhood in Lisbon, where I lived for two years, and the way in which its architecture, its flora and its people, especially young people, share the same space. In the book they end up standing for different kinds of timescales and historical dimensions. Again, it is about using different “ingredients” to reflect on some kind of anachronism, and again there are speculations about power and history (the neighborhood in question was built during Salazar’s “Estado Novo”). I am very happy with the result, although it is a work of a small scale I think it succeeds in creating a consistent atmosphere and in articulating a limited but meaningful set of thoughts. It’s something I have wanted to do for some time. It was also a laboratory I could use to start working more consistently with people, by stopping them in the street, asking them to pose for portraits, and trying out different strategies. Now I feel that when it works it does so because of a particular balance I am interested in between staging and chance. My favorite images are the ones in which there is a slight contradiction between the statuary solidity of the traditional portrait form and the randomness of the street shot. There are a couple of images in the book that do that. It also might be the best I have achieved in terms of color, but that’s another story.

In Eel Soup I tried working within a more comfortable environment, which on the other hand was something I had never done, that is, to take pictures of my more private everyday life. It started out as a game, and as a response to a need I felt to take happier pictures. I wanted to do something joyous and even funny or cheesy if I could. Tami started inevitably appearing in the pictures, and she wouldn’t let that happen without participating in some way. At first she would just come up with ideas for photographs or start “taking over” from inside the frame, playing with me. I wasn’t used to it, and it was huge fun, it took a lot of seriousness out of the portraiture, I didn’t feel the pressure to resolve the pictures or negotiate them because of the power I was joyously letting go of. The work soon became about us, in a way, and when Tami started working with ceramics it was all taken to another level. Both of us kept on exploring what was coming out of the photographs of her on our own. I would drift around and take pictures and she would work on ceramic sculptures. We knew what we were working on but couldn’t pin it down in words. We would talk about “entanglement”, “multiplicity”, “viscosity”, “pressure”, and so on, but above all we would look at pictures and jot down ideas for sculptures. I have never been used to working at such a material level. The fascinating thing for me is the feeling of approaching something we feel is the same object but by means of very different material processes, one of them optical and the other haptic, one of them 2D and the other one 3D, and so on. The way we decided to show the work in Poland plays with these differences by installing mirrors on top of the plinths we used for the ceramic pieces. Our idea was to transform the sculptures themselves into some kind of optical device capable of framing the prints. I have never been so happy with an exhibition. Any of this would have been unthinkable for me if it hadn’t been for such an unexpected collaboration.

Federico Clavarino

Skinnerboox

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Brad Feuerhelm. Images @ Federico Clavarino.)