Alejandro Acin

The Rest is History

ICVL Studio and supported by

Sala Kursala Programa Cultural

The machinations of history are in constant flexes of exchange. They are impermanent, their concept a flux, or are often a mess of contradictions. We are taught history as if it were permanent, an established and often binary set of positions best exemplified by winners and losers, victories and defeats. There are the alleged key players, whose names are scribbled on parchment and at the base of statues that come to be seen as godheads for whichever episode of time, collective insistence declares them relevant. Some are reviled. Rarely is history taught as an aggregate of voices or positions, though multitudes take part in their notification.

The challenge of history is not that it exists as such through the written word, oral tradition, or memory, however imperfect, but rather that history exists at all. Perhaps all that can be afforded is that the measure of civilization and its histories are best left buried under sand, with all remaining quills broken before the attempt to define a moment as historical can be attempted. I suggest this because I disagree with all of history and that I am dismissive of its ascribed point of value.

The second token missive of history is that as a civilization, we believe that it can be informative, that in recording the travails of the people who suffer or prosper under it, the ontological capacity of history should be seen as educative. Yet, I see no example where humans have ever made the best of their misfortune by never repeating their tragedies. In fact, history is a poor educator. In fact, these moments of historical infamy and declaration instead seem to imply a cartographic resonance, a way for humans to re-engage with similar paradigms, no matter the human fodder caught in the gears of its machine, all gristle, bone mash, and burgundy lubricant, only to come out of the grinder and repeat. History is not only a fallacy but also a dirty aggressor.

Like language, history is something closer to a virus, a living and amorphous concept that, like a succubus, needs another being, or better, multitudes, to feed its condition. It is conceived somewhere at the back of the throat, in the basement of the human mind, where the primordial tenet that fears above all mortality without consequence resides. The place where nothingness chips away reason, one hammer strike at a time, slowly so as not to raise too much awareness of its presence and actions. Any parasite knows to drink blood slowly and over an expanse of time to not kill its food supply or make it aware of its feeding.

Fear is the most realistic term for defining history and its concepts as the winners do not write it; it is written by the temporarily fortunate, and those who project an infantile need to be part of some moment, with all disregard to the fact that they were and inconsequently shat out of the polluted womb of the universe into one place over one very unnoticeable moment in time only to scream back from where it came from that it exists and demands in as much, to be noticed amongst all the other excrement shouting back the same inane buffoonery. The basis for fear as historical analogism is not that we end tragically but that we end without a testament. Therefore, the invention of history is nothing more than an absurdly painful concept that doubles down against humanity, suggesting something lasting, irreverent, Godlike, and war-oriented. It is inhumane and cruel and should be seen as the tapeworm that it is, lodged in the bowels of human consciousness as a possibility.

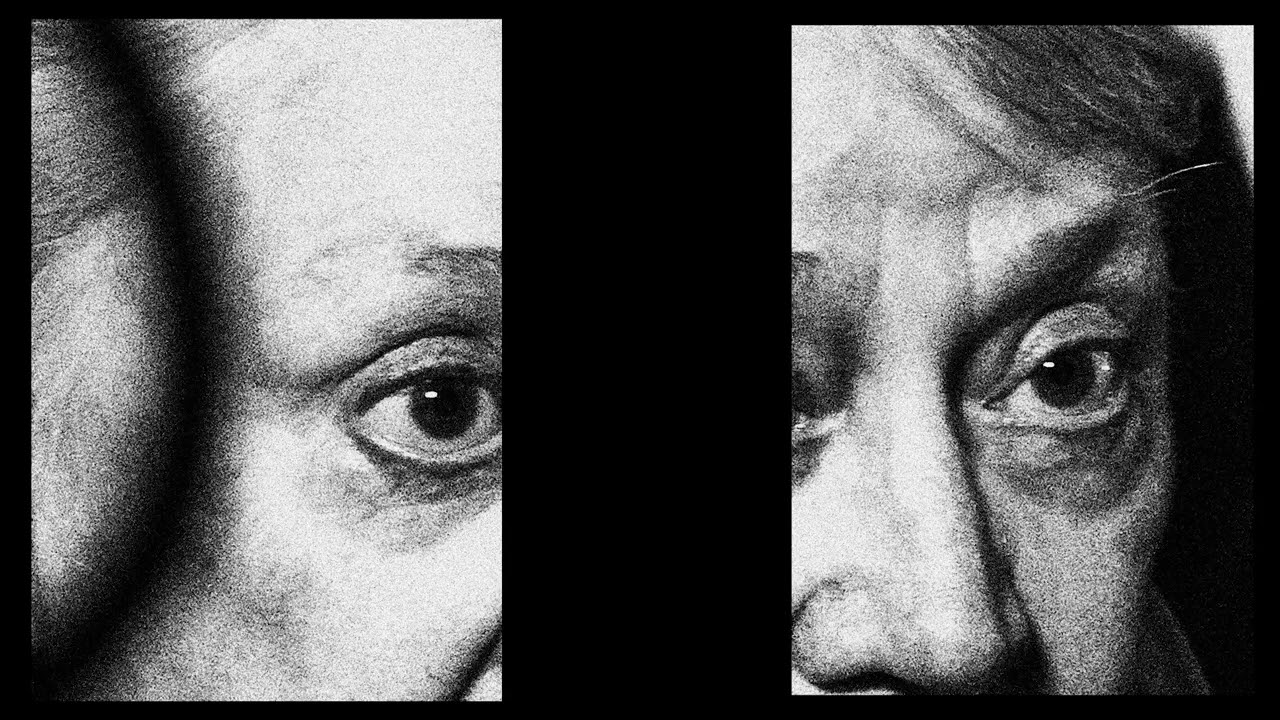

Alejandro Acin’s The Rest is History, published by ICVL Labs, is an anti-testament to history. Throughout, the artist uses indexical means and timestamps to document Brexit Day in the United Kingdom, the last day and minutes before its secession from the European Union. The book seethes with a palpable anger and yields a purpose-built investigation of the alarming nihilism found in such “historical” moments. The photographs of people on the street caught by high contrast nighttime light remind one of the great protest books of the 70s, particularly the Provoke Era in Japan. I am reminded of a mix of the aims of Shomei Tomatsu’s Oh! Shinjuku, Frank’s The Americans, and perhaps Christopher Anderson’s later photobook Stump. The focus is on the listless amounts of people coagulating in public places, presaged by presumed marches, celebrations, and an errant form of toxic colonial nostalgia filtered through the gritty implied criticism of the artist, a non-native British resident.

Though there is an implication that Acin is focused on the moment as history, what I derive from the book is that it is feverishly impossible to calculate a valid type of history with so many moving parts to the machine. In some ways, to have anger is to hold onto hope as the encroaching headwaters of nihilism break the shoreline. In this sense, one ponders if such a book can have a resolution as it still wants to be involved in the conversation surrounding political economy and change. Though I have sincere reservations about history as an idea, I enjoy the work more as it captures something unattainable, the atmosphere of the human motivation to be included in something and to be defined by that position, however unheard the actual reality is.

I would say that the most vital aspects of the book are more technical than conceptual, and that is not a criticism of the conceptual grounding. The diminutive and solid book motivates the viewer towards enlightenment by conveying atmosphere through intelligent and minimal design. The uncoated paper and the deep-set black inks remind one of the eras of gravure printing. It is as close as one can get to that technique with offset printing, and the overburdening black thickly etched across its pages pull the viewer into the void, looking for clues, glimpses of the recognizable. The edit itself is from a collaboration between the artist/designer Acin and noted artists and writer Julian Baron and Isaac Blease.

An excerpt from the full interview with Alejandro…

BF) Photography and History are often intertwined by the motivations of photography and its (un) reliability as a document. It is meant to convey a moment or a time, yet, around every corner, it eludes the realms of representation. How important was it for you to make the work to treat your photographs like documents, or were you interested in destroying the notion? I will admit I see the images as something that accentuates the problems associated with documenting history…

AA) The premise for this work was very simple, to document the last day of a historical relationship. I wanted to establish a dialogue between the past and the present, and to do that; I focussed on two very symbolic places in London: The British Museum and Parliament Square. One for being the historiographic factory of the nation and one of the world’s largest and most comprehensive collections of antiquities from the Classical world. And the other, for being a public space – originally designed to inspire the Victorian public with remainders of Parliament’s glory and monumentalised examples of statesmanship – which in recent decades has been the arena for public demonstrations about political events such as the suffragettes, the miners strikes and now the Brexitiers.