“You know, the way that if you can stay curious about something, and keep attending to what it is in this moment of encountering it, there’s always more to discover”

ZD: I wanted to kick this off with a fairly straightforward question, but it might turn out not to be one. You mentioned your interest in the idea of how the more you get to know something, such as a place, a person, a concept, the more mysterious it actually becomes rather than the vice-versa, which is a popular misconception. Can you elaborate a bit on this, what role does curiosity play in your work in general and what do you think photography’s part in becoming familiar with something or someone is? It’s such an interesting tool, photography, it influences memory in particular in a way that no other medium (painting, for instance) does; not only does it record but I also find that the more you photograph a face, for example, the more comfortable you become around that person, not merely because you spend time together but also the image itself rather than the person starts living in your mind’s eye. I feel like this idea of the nature of photography at its very core is crucial to your work, especially nowadays when most photographs are shared online, which is enabled in a way by the subject of your pictures.

AS: Ha! Something that seems straightforward but turns out not to be. I think this is what keeps me engaged with photography.

That relationship you mention, between attention and mystery, feels really important. I’ve always found there’s something weird about looking at things. You know, the way that if you can stay curious about something, and keep attending to what it is in this moment of encountering it, there’s always more to discover. I think it’s only when our curiosity runs out and we accept an idea about something—an object, a person, a place—that this mystery diminishes. The sprawling strangeness gets tidied up and reduced to the idea we have of it.

One of the things I love about walking around with a camera is the way it helps me let go of some of my assumptions about things, to disrupt the ideas and images that have formed in my head and to loosen my grip a little on the categories I use to order and navigate the world.

As you say there is something comfortable about familiar concepts and images. They are essential in many ways, allowing us to create meaning and achieve a feeling of stability in a world which would otherwise be totally overwhelming! But things are always more mysterious and expansive than the categories we put them into. It seems to me that a desire to hang on tightly to straightforward answers—to believe things maintain fixed identities and fit within rigid boundaries—is linked to so many of the problems we face right now.

The photographs I love most point into and outside of themselves towards a world of indeterminacy and entanglement. They manage to capture the strangeness of becoming aware of what is in front of us. To convey a relationship between lucidity and mystery.

ZD: I love how the design of your book, Known and Strange Things Pass, gives a hint of what’s contained inside. Its size (not too huge but certainly not as small as I thought it would be!) manifests that it’s quite a complex body of work but also the way the cover gives away some of the content (entanglement, grid-like structures, etc.) and the form it takes (the little strips on the top and right hand side). It’s great that you’ve managed to make a cover which reflects the work without actually using any pictures.

AS: Thanks, Zak. Yeah, I really like how the cover introduces some of the tensions that play out inside the book. For example, the grid. This is something I’m actively working with and against when thinking about how things exceed the patterns and categories we fit them into. Nicolas Polli, the designer I collaborated with on the book, references this in his cover design. We see a grid—the grid that was used and deviated from when laying out the book—with these black pictures pressed into the cover that don’t quite sit within the lines. And as you hold the book the glossy surface of these black pictures pick up your fingerprints—echoing the signs of touch and contact that are another theme of the work.

I also love the paper we have bound the book in, it has a fleck running through it that feels a bit like white noise, a bit like sand, a bit like concrete.

ZD: The concept of time and its passage appears to be central to the work – the strips signifying the fragmentation of memory and the way we perceive reality but also the pictures that were seemingly taken only moments apart, they kind of remind me of Paul Graham’s A Shimmer of Possibility, almost cinematic and maybe referring to the 24fps (or 30fps or whatever current filmmakers use). I think you mentioned peripheral vision to explain how the strips work visually, could you elaborate on it? I get the same impression, to me they both appear to be showing what I saw moments ago on previous pages, so as if a visual residue, but also point at what’s to come next – some of the pictures appear again later in a slightly different form so they’re almost the same as when you close your eyes but for a few seconds you still see what you’ve been staring at before, in my mind at least.

AS: You’re right, the concept of time is central—especially our experience of it and the way different times intermingle. And time, of course, is always inextricably bound up with space. For me the space and time between things is a really important part of this work.

In the book layout I was looking for a feeling of fluidity and interrelation where the size and position of each picture feels shaped by those around it. I wanted the design to help articulate the strange and complex way things are entangled with each other. So, instead of each picture being contained by the fixed edges of the page, they move across this boundary, spilling from one page onto another and implying a bigger set of connections beyond those we can currently see.

Something people have told me, after looking through the book, is that they feel like they’ve been at an exhibition. I really like this response. The way the design conveys an experience of moving around. And of how, when we look at one thing, the edges of others are always in our peripheral vision. People have also picked up on the way the design helps to reinforce the spatial relationship that exists between the ocean and the Internet. The way they aren’t just good metaphors but that they are also directly and mysteriously part of each other.

And as you say another element is the way the work’s structured through these intermeshing sequences. A kind of cinematic crosscutting allowing things in different times and spaces to intertwine and coexist. Really, in a way, this is what the work is all about—developing relationships that feel important and real but can’t really be expressed in analytic terms.

I like what the repetition of pictures with barely perceptible differences does to the flow and rhythm of the work. At first they read like a glitch. Haven’t I seen that already? They send the viewer back to the previous instance to compare it against. When viewing photographs in a book, unlike when watching a film, we are in charge of the temporality. We can go back, we can flip forward, and in doing so we can jump over the pictures in between. The near repetitions in Known and Strange Things Pass encourage this jumping and when we do so we skip over pictures which are themselves often linked to others that come later. These spatial and temporal links—the collapsing and opening up of relationships—are important to the core themes of the work and to its cohesion. They help to form threads that bring things into relation we normally think of as separate.

“I like what the repetition of pictures with barely perceptible differences does to the flow and rhythm of the work. At first they read like a glitch. Haven’t I seen that already”

Paul Graham, as you say, is an influence. I love A Shimmer of Possibility, the sense it conveys of moving through a space and noticing what is there. And there are other influences too, Guido Guidi and Robert Adams, for example, who have made great use of repetition and sequences that unfold over time.

ZD: I imagine it was quite an educational project for you, presumably it taught you a lot about the way the Internet works. Have you noticed any change in the way you use it or think about it since finishing the work?

AS: Yeah, I guess all projects are a kind of education. You know how it is, there’s this kind of gradual realisation—ah, ok, so I’m attracted to this or repealed by that. What’s that all about? Why do these things, these pictures, excite me or make me anxious or confused. A project is a way of learning about these feelings.

I also did end up learning a lot about the infrastructure of the internet. I needed to research where these cables were, how to get access to them, etc. But I also did a lot of thinking and reading about the Internet more generally, about the sea, about Victorian telegraph cables, about embodiment and disembodiment and how technology affects these feelings, about how very large objects like the sea or the internet affect us, about Kant’s ideas of the sublime, about Deleuze’s rhizome, about Morton’s Hyperobjects, about how we hold ourselves in relation to the world around us, about touch and trace and entanglement and vulnerability and power and the indeterminate . . . All of this is fed by the pictures I’m making and feeds into what the work becomes.

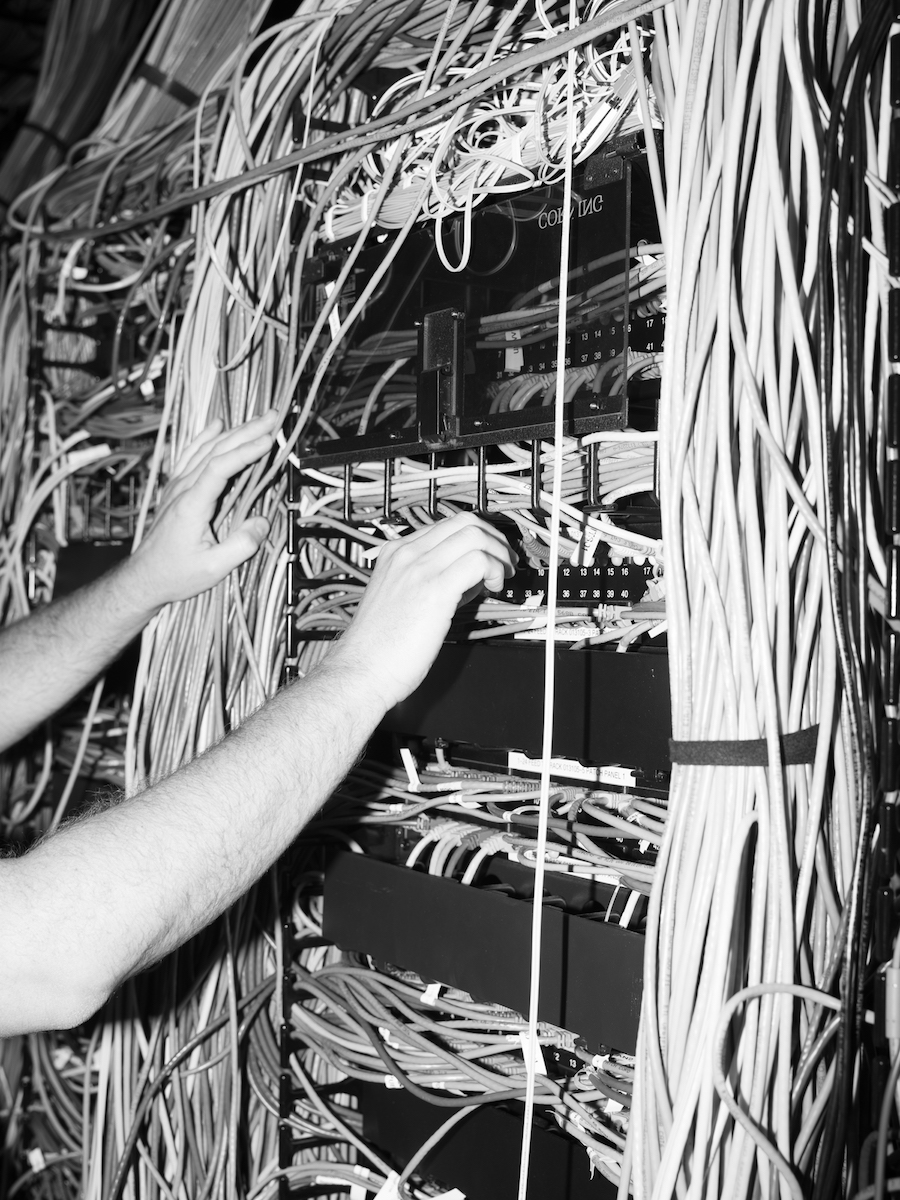

And of course all of this changes how I think about the Internet and many other things. I do remember when I first read about the cables – finding the idea of them really surprising. I guess until that point I’d assumed data was flying around in the air and bouncing off satellites or something like that. The material existence of the cables (that they are tangible things) combined with the knowledge of what they are (points of concentration through which almost everything we do online passes) felt so strange, both super abstract and deeply grounded.

The ocean and the Internet often get spoken about in terms of the sublime but they are not just useful metaphors for each other, they are physically entangled. In a way this is what I’m trying to figure out—how to use metaphor to speak about something that is more straightforward but perhaps harder to grasp. A materiality, a complex spatial and temporal proximity. And vice versa, how to use the slippery straightforwardness of photography to speak of things that are hard to picture.

There were questions I was trying to articulate. How do these vast, unknowable objects – the ocean and the Internet – speak to each other, and to us? How do they relate, these things we think of as being completely separate, but that when we look closer, are literally and metaphorically enmeshed with each other.

ZD: Could you tell me a bit more about the way you worked with text, both in the book itself and in the small booklet? There’s the essay but I’m more interested in the other text with its unusual layout, upside down, sideways, etc. It goes quite nicely with the cover!

AS: Yeah, I like how the text and the layout of the pictures echo each other in different ways.

With the text there was a balance I was negotiating. I knew that I needed to give the audience enough to set up the idea that frames the work— that all the pictures are taken in places where the internet is concentrated, where the fibres of the network come together, and almost everything we do online passes down a few impossibly narrow tubes, stretching along the seabed, connecting one continent to another. But obviously text can really close down our reading of pictures and I was conscious of not wanting the work to be reduced to a discussion of infrastructure or any other single idea.

I suppose what I’m always searching for is something that feels expansive. That always has within it the possibility of new meanings. Something seductive, which feels meaningful and pulls the viewer in, but doesn’t resolve easily.

So in the book itself there are just two captions. The first telling the viewer they are looking at “One end of submarine fibre optic cable carrying the Internet between Europe and America. England, SW Coast” and the second stating this is “The other end of submarine fibre optic cable carrying the Internet between Europe and America. USA, East Coast”.

When thinking about what text we should include, Nicolas said he’d enjoyed hearing the behind the scenes stories—the encounters I’d had and ideas I’d been grappling with. He suggested I should have a go at writing some of these down and we talked about creating a text that echoed the structure of the book. Fragments, lines of thought, and recollections, that would intertwine with each other in a similar way to crosscutting that happens with the pictures.

This was something new to me, this way of writing, but I liked the idea and we were in lockdown so I had time! I really enjoyed putting it together and think it adds something to the work. For me the text both pins down and opens up the what’s happening in the book. And vice-versa, the book opens up and pins down what’s happening in text.

Andy Sewell

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Zak R. Dimitrov. Images @ Andy Sewell.)