It embodies Campany’s belief, “that photographs don’t have meanings: they have potential for meaning. It’s a question of how they’re used.” Or rather how we decide to see them.

THE AMERICAN TEMPLE

By Vladimir Gintoff for ASX, October 2013

History often reveals itself in unexpected places. Take Salt, Mark Kurlansky’s non-fiction opus on how a mineral was able to alter trade routes, construct cities, provoke wars, secure empires, prompt revolutions, and even be used as a currency. In our globalized era the influence of commodities is even more pronounced. Look at Dubai, before oil was discovered in the UAE during the 1950s it was a port town of low lying structures, now it is home to the world’s tallest building.

David Campany – artist, writer, curator, and Reader in Photography at the University of Westminster – recently published Gasoline (Mack, 2013), a book of newspaper photographs depicting gas-related events between 1944 and 1995. It is a sampling of twentieth century car-culture, filling stations, and other accouterments, primarily in the United States. The prints were collected from North American newspapers in the process of liquidating their print archives.

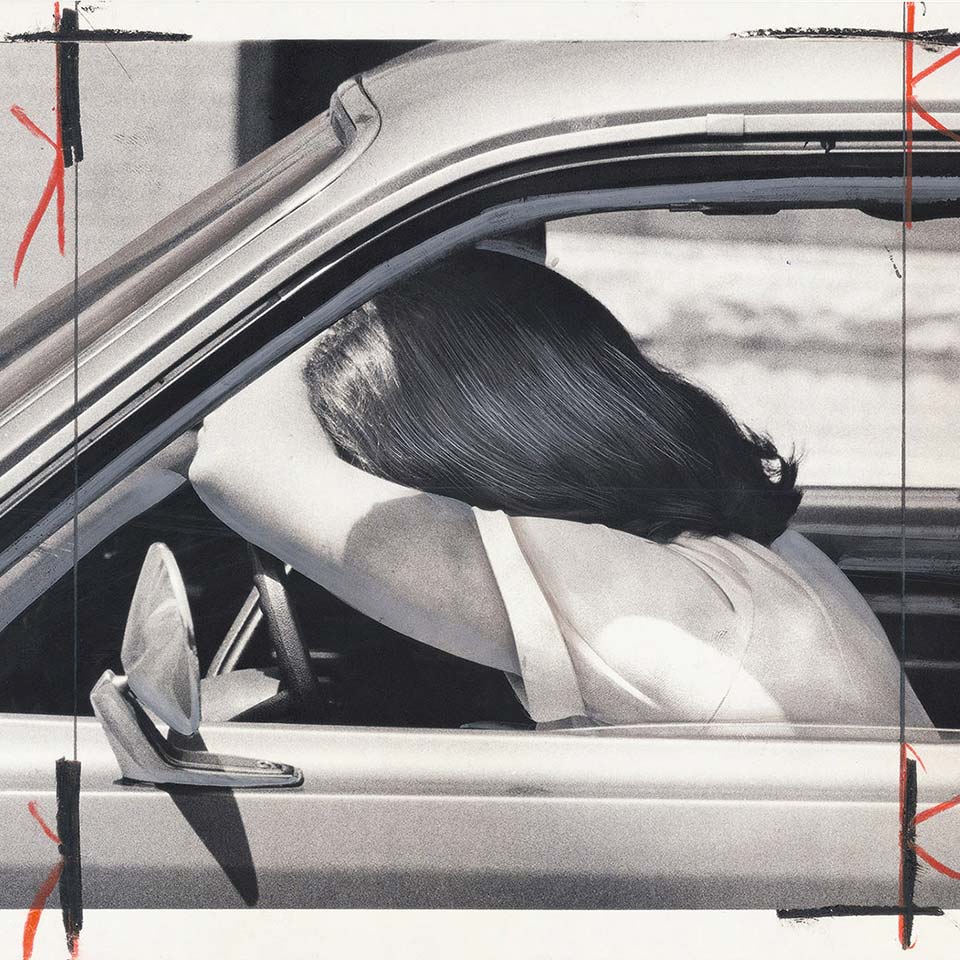

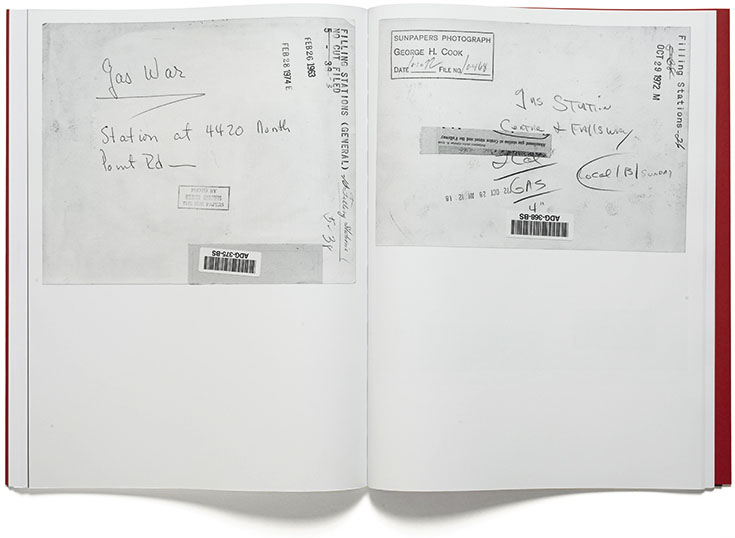

Gasoline is split into two sections – fronts and backs of the photographs – separated by a short interview with Campany, printed in silver text on toothy black paper. The book is soft-cover, but stiff, with a red paper dust-jacket, similar in size and color to a school folder. The title shares the cover with a photograph of a woman in her vehicle, arm draped across the steering wheel with her face obscured. The car, the woman’s hair, and the sunlight are all airbrushed to perfection. It could be an advertisement or a fragment from an early Rosenquist painting.

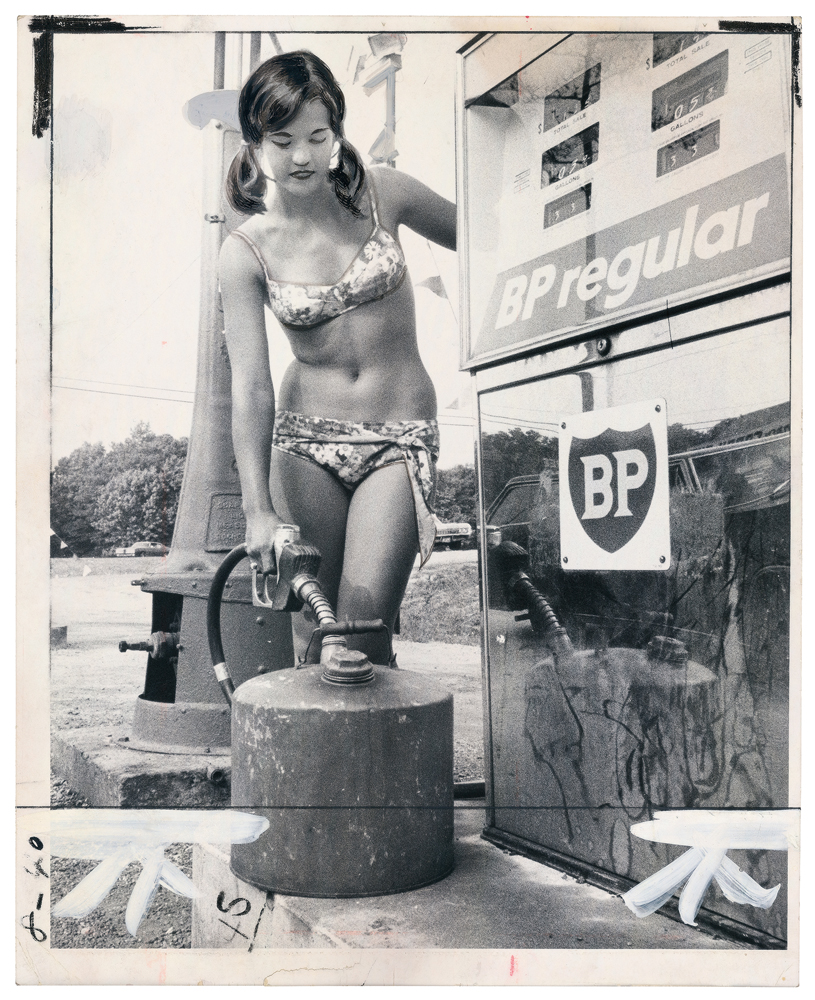

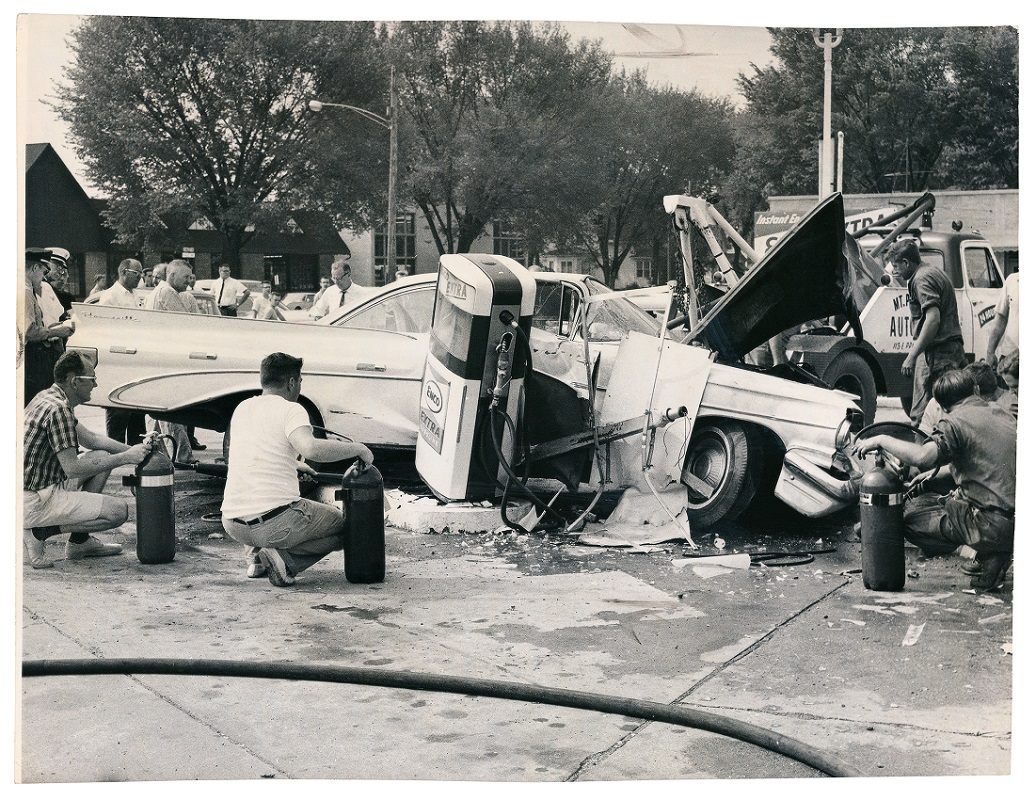

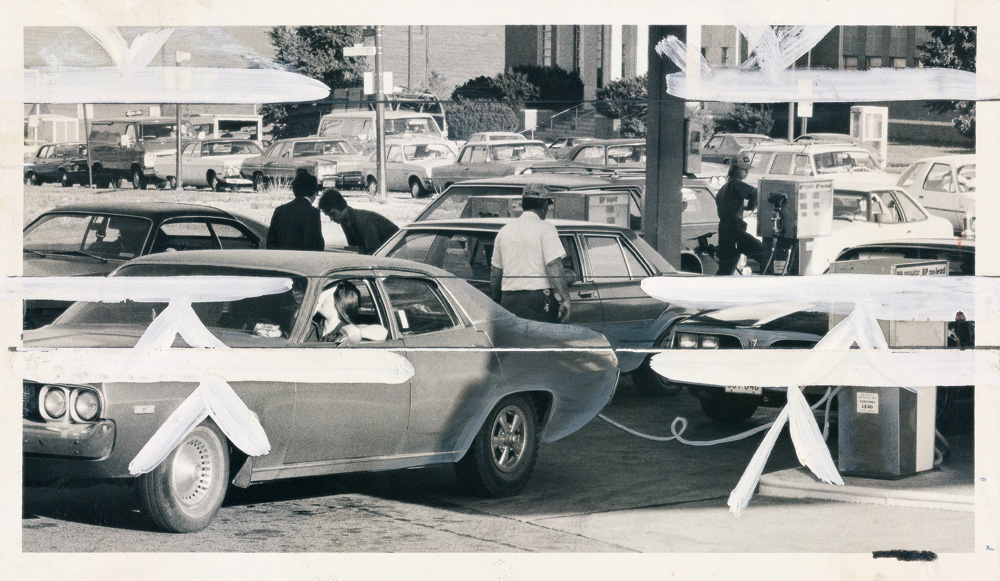

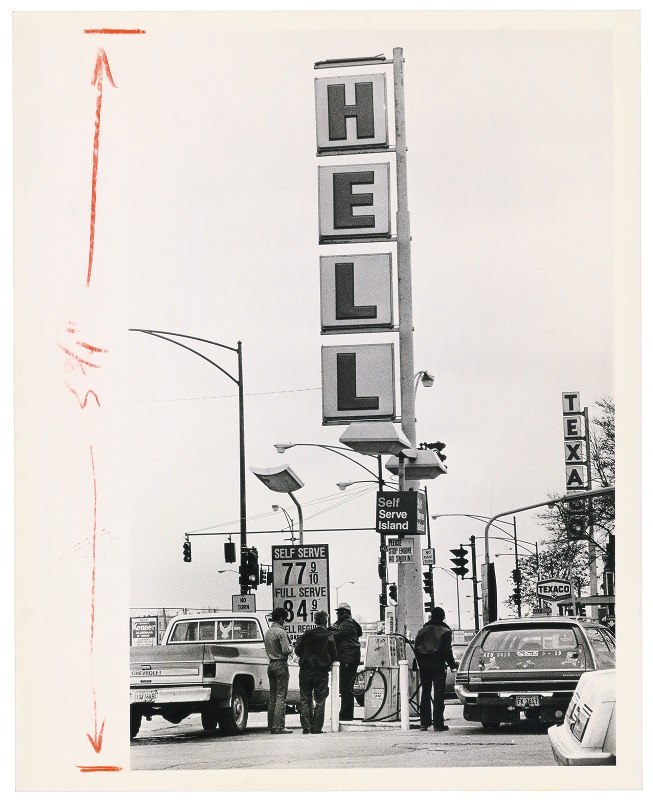

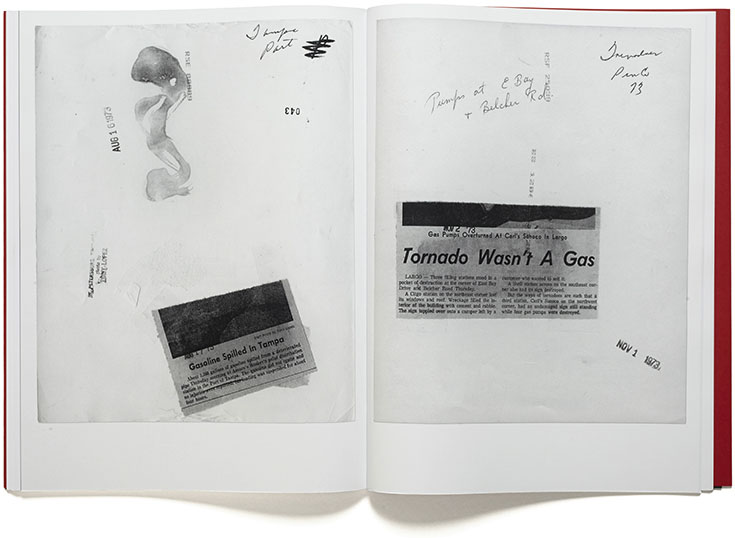

Many of the photographs are annotated with grease pencil. A combination of crop-marks, cross-outs, and beautification, all to achieve a journalistic bent. The markings are evidence of a mediation process that alters the documentary eye of the photographer into the demands of the newspapers, and finally, to a reflection on history, media, and photographic objects by Campany. This evolution of meaning and intention arrives at a time when postmodern art practices are strongly resurgent with the likes of Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, Erin Shirreff, Anne Collie and numerous others. Campany does not take credit for these photographs, but as a curator and author, he reveals nuances of culture through an unlikely source.

Today, the virtual world has increasingly taken the place of the open-road as the source of ultimate freedom.

What appears to be a visual history of a commodity, Gasoline yields many levels of appreciation, including photo-journalism, nostalgia, period aesthetics and photo-books. It embodies Campany’s belief, “that photographs don’t have meanings: they have potential for meaning. It’s a question of how they’re used.” Or rather how we decide to see them. The argument brings to mind Sultan and Mandel’s Evidence (Clatworthy Colorvues, 1977), where photographs of government agencies, public institutions and corporations, are displayed without their original context, and requiring interpretation. In Gasoline, the backs of images share some facts – headlines, names, numbers, and bar-codes – but the information is often obtuse, and, like Evidence, it’s more refreshing to be left in the dark with our imagination and assumptions.

(From Gasoline © David Campany, 2013, courtesy MACK)

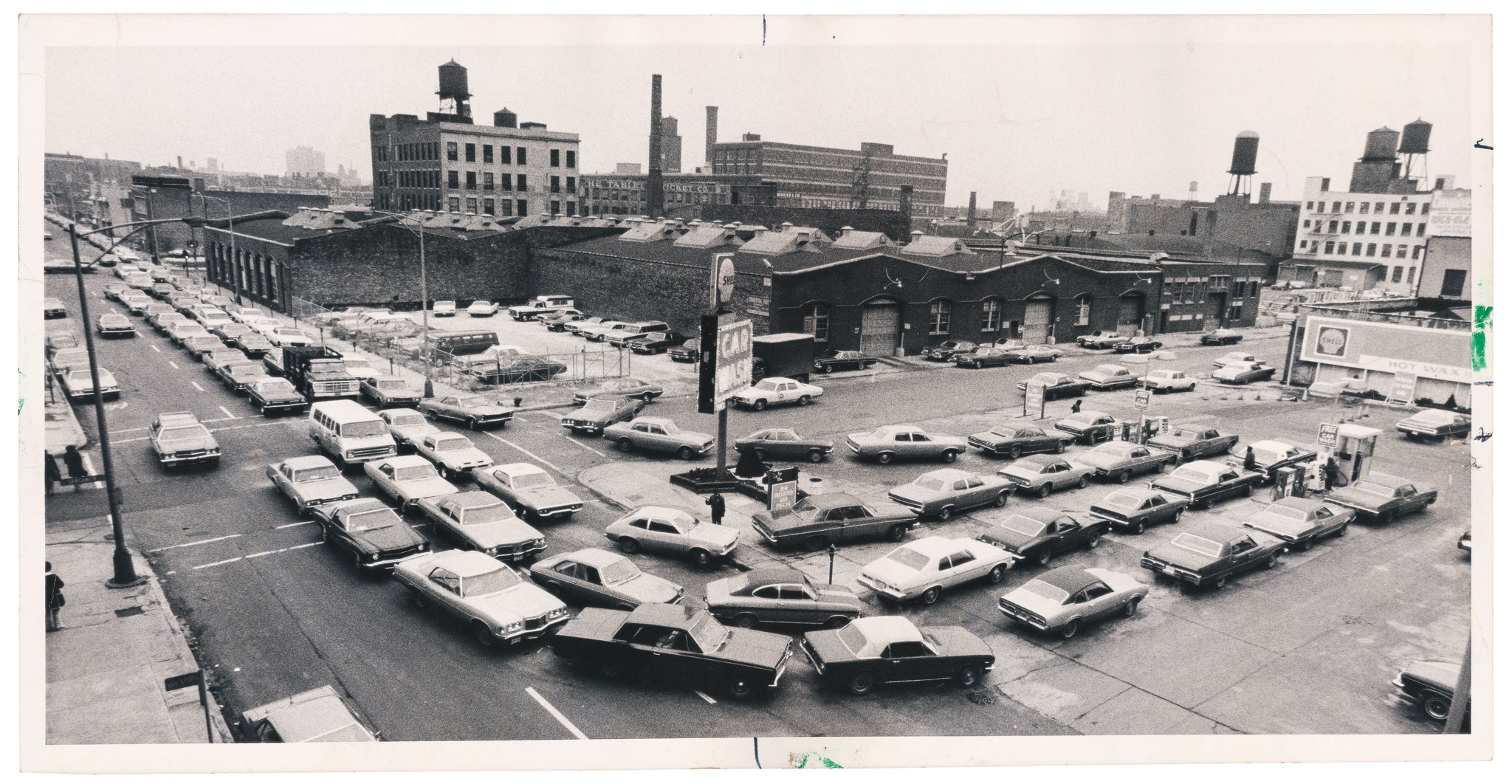

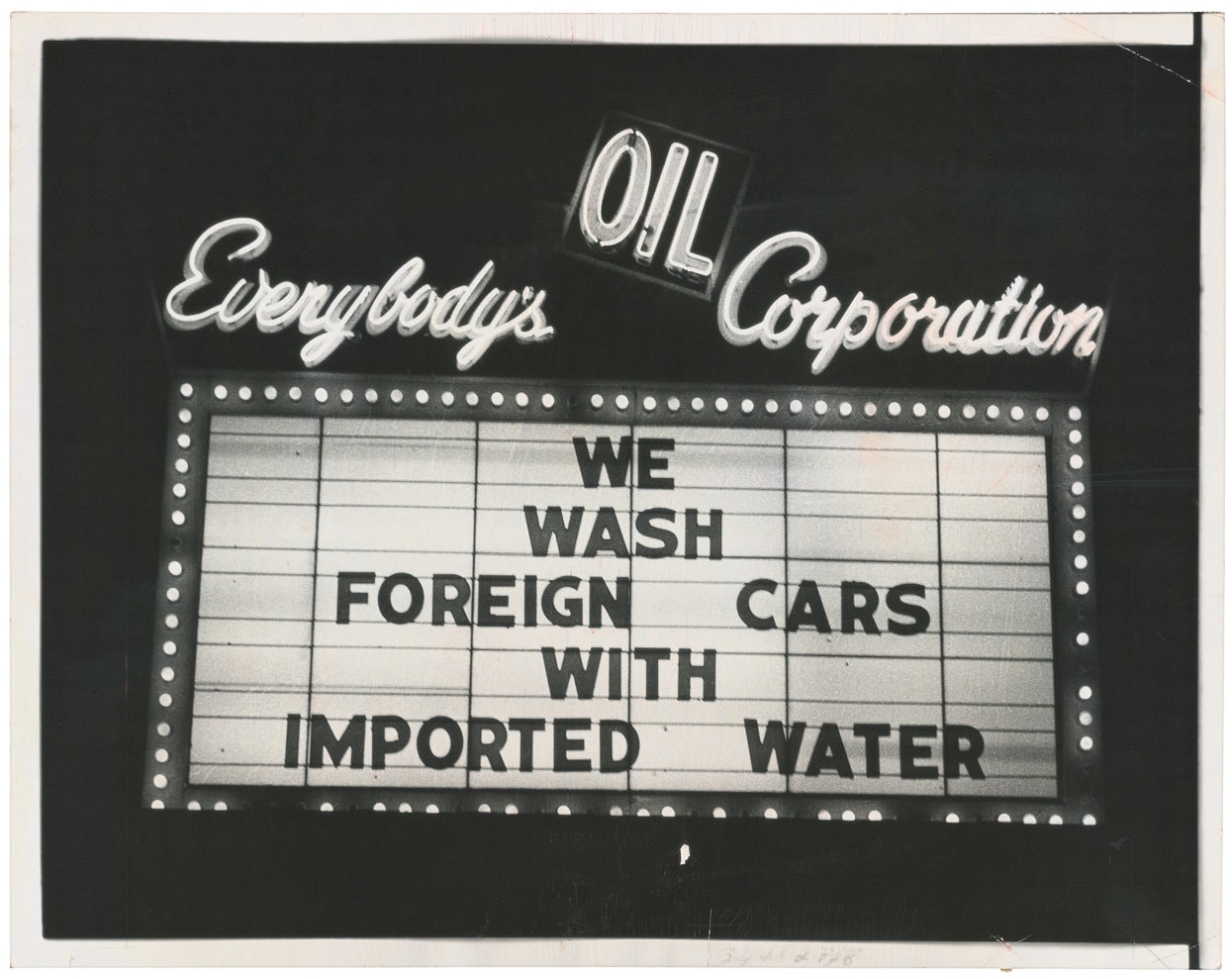

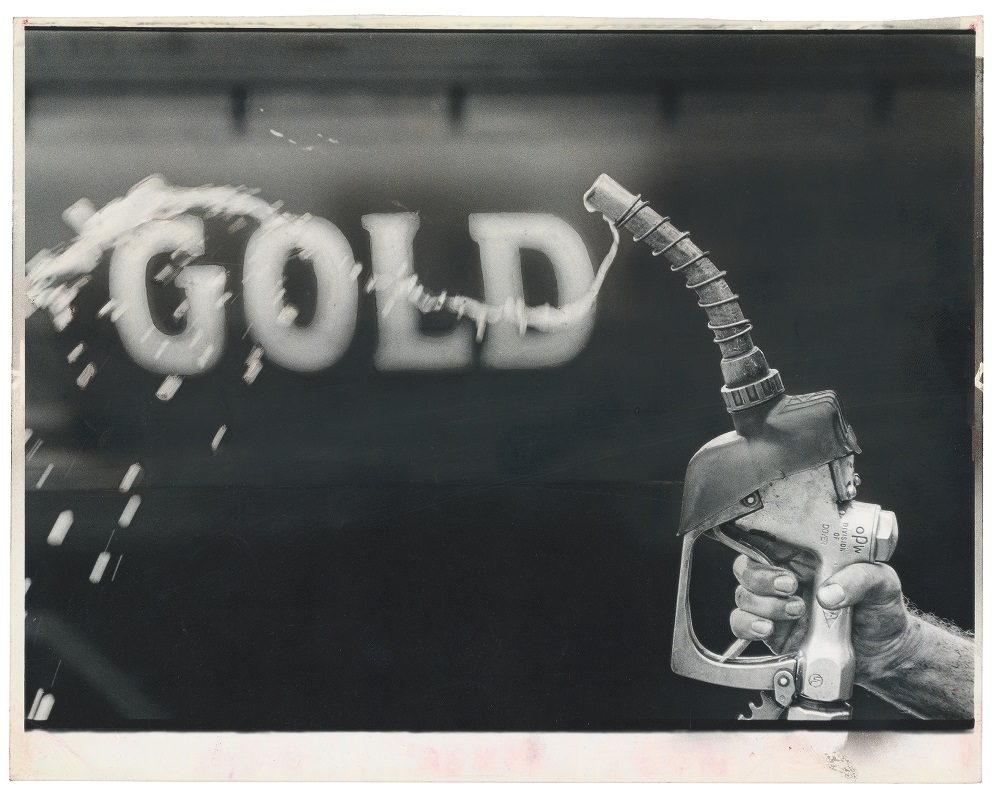

There is also the looming precedent of Ed Ruscha’s, Twentysix Gasoline Stations (self-published, 1963). A book, says Campany, that “describe[s] a world without events, a sort of modern pastoral.” Gasoline is nothing like this. What is shown is a world of accidents, crimes, gas shortages, and economic crises. Like Ruscha’s book, the focus is on the signs and symbols of our culture, and the news is secondary. Our twenty-first century eyes are enthralled by the bold fonts, cheap gas prices, company logos, attendants in uniform, patrons, gas station architecture, lines of automobiles, and the attention-seeking, “folded paper” designs of 1970s American muscle-cars.

It was a time when Americans still revered the car. An era when driving was our newfangled religion and the gas station our temple.

It was a time when Americans still revered the car. An era when driving was our newfangled religion and the gas station our temple. The relationship began to sour during the 1970s – which Gasoline covers liberally – when gas went from a given to a privilege, no longer presenting the illusion that there was an infinite supply. Today, the virtual world has increasingly taken the place of the open-road as the source of ultimate freedom.

(From Gasoline © David Campany, 2013, courtesy MACK)

The word “gasoline” intentionally simplifies a broad topic, by bringing a range of events into a common category. While the photographs were ordered and selected by Campany, the resulting eclecticism is similar to searching for images online, where keywords and algorithms supplant subjectivity in a visual grab bag. Gasoline, like the web, exposes the volume of photographs that exist, but instead of falling victim to the magnitude, it provides a tight, organized edit of pictures, which reveals the nuances of society through a topic of global ramifications.

Gasoline by David Campany

Softcover with dustjacke

24 cm x 32 c

100 pages

37 colour and 37 black and white images

ASX CHANNEL: DAVID CAMPANY

(All rights reserved. Text @ ASX and Vladimir Gintoff, Images © David Campany, 2013, courtesy MACK / www.mackbooks.co.uk)