“When I began to take photographs, I never imaged that my photos would travel around the world.”

Interview in Madrid for the PHotoEspaña Baume & Mercier 2009 Award

Since 1960, Malick Sidibé (Mali, 1936) has produced photographs in his studio, Studio Malick, located in Bamako. These images with their pure gaze document popular culture in his city. As a result, Sidibé has achieved producing photographs far removed from the prejudices of a Western gaze cast upon other cultures.

Malick Sidibé waits for us sitting in Oliva Arauna Gallery, wearing a long green tunic with white abstract drawings. When we arrive, he greets us with a wide smile as if his eyes were smiling, too.

Right away, his presence fills the room, captivating us. He’s the kind of person that doesn’t leave you indifferent. He speaks with enthusiasm from the start, remembering every minute detail in his photographs even though fifty years have gone by since then.

At times, he seems to be far away as if he were suddenly taken back to his studio in Bamako. He speaks with his eyes closed, remembering those days when he took portraits of his country’s history, which turned him into one of the most influential photographers at the time.

PHE- Today you’re a renowned photographer, and your photos have traveled all over the world. How did you start out in photography?

Malick Sidibé- I studied at the school of arts because I liked to draw. Then I began in photography by working with a French photographer in 1957. At the time, I was the youngest photographer in the city.

“Young people enjoyed having their photo taken in their best attire, with their new earrings, curled hair, showing off their best watch, their bracelets… Everyone likes to be beautiful in photographs.”

Luckily, I was the only one who had a flash, so I began to take photographs of parties at night. I was at the studio until midnight or one in the morning until I went out to take photos at parties. I would go back to my studio, develop the film, and on Mondays and Tuesdays I would hang the photos in my shop so young people could come and choose the ones they liked the most.

My studio was always lively because all the young people would come to see photos of the parties. I got to know all of them, and today I still remember the faces and names of a majority of them.

PHE- Mali’s independence came about in 1960. How did the new political situation influence your own work?

MS- It wasn’t so much our independence as it was Western music that changed many things during that time. Music was really the revolution because after 1957, rock music, hula-hoop, swing, etc., came to the country. Music was a true revolution in Mali.

PHE- Aside from the photos of parties, you have a large quantity of studio portraits…

MS- I began to photograph young people at parties after 1957, and then I went on to portraits since photography has a wide tradition in Mali. For people in my country, it’s important to have photographs of themselves to be able to show them to their family, their friends… It’s a kind of social gesture.

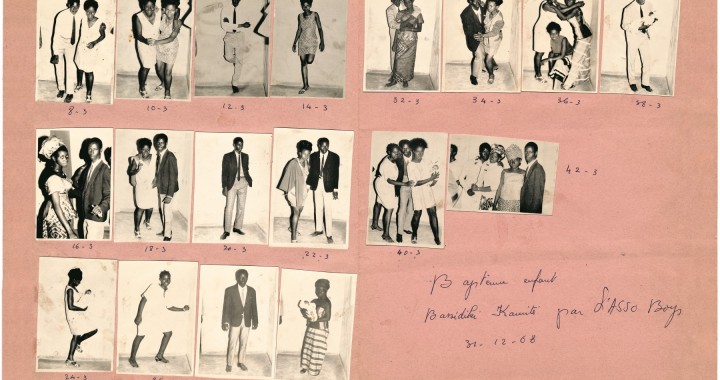

Ever since the 1960s, I started to take photos in my own studio. Everyone went there because taking a portrait at that time was very inexpensive. More than anyone else, young people enjoyed having their photo taken in their best attire, with their new earrings, curled hair, showing off their best watch, their bracelets… Everyone likes to be beautiful in photographs.

There were people who wanted to have their individual portrait taken to send it to their friends, always wearing new shoes, a tie… There were also people who wanted to have their photo taken with their herd of livestock, with their motorbike… to show their possessions to everyone else, to show their lives to others.

PHE- How would you assess the evolution of your work since you began until now?

MS- When I began to take photographs, I never imaged that my photos would travel around the world after only a few years. I took photographs for people, for my country… I never could have imagined what happened next. My photographs are a kind of tourism because it’s as if you’re traveling to Mali when you see them. Photographs are reality: they never lie, and that’s important to me. I’ve developed all of my own negatives and have them categorized in my studio.

PHE- The means for photography have changed a lot in recent years. However, you continue to be faithful to analog photography…

MS- I understand that digital photography is simpler and much less expensive, but it’s not a true photograph for me. In analog photography, you have to focus the image, go to the lab, develop and work at it. Analog photography can’t trick you since it shows all of reality. In digital, you can manipulate the images.

For example, with analog photography, you take a photo of a dog, and then you can see how the dog was wagging its tail… All of this is reality.

PHE- In your extensive career in photography, many of your photos have made history, turning into true icons for an important era in your country…

“In the 1960s, girls would sneak out of their houses to go dance. They would put something in their father’s glass of water so he would sleep and not notice when they left the house.”

MS- I’m very satisfied with my professional life. It’s difficult to choose a good moment. I have a lot of photo negatives, and there are many photos that I like quite a bit. For example, I like the portraits of small children, the ones in which they’re smiling. That gives me great satisfaction. This photo with a dancing couple is among those that people like the most, and it’s the most well known. It’s called “Christmas Eve” (1963). It’s not the one I like the most.

In one of my favorite photographs a very elegant boy is dancing with the daughter of Mali’s Prime Minister. Today this woman is Muslim, and she wears a veil. If she were to see the photo, I’m sure she would say, “That’s not me”.

I remember the names of almost all the people who appear in my photographs. If I can’t remember their name, I remember their father, what they’re doing now, if they have children… I also like the photograph of a Nigerian boy who used to be a designer. In this photo, the boy opens his arms and says: “Life is marvelous”.

PHE- Your studio in Mali is still in operation today. Do you still take photographs there?

MS- Today, foreigners—mostly from Europe—are the ones who go to my studio to meet me because they’re people who know the history of photography. They go there to have their portrait taken.

Something curious and extraordinary is that now all of Mali knows my studio. Children, who normally call grown men tonton or “dad,” call me by my name, because names are the most important thing for artists. There are also women from the countryside who have named their own children Malick, and that fills me with pride. I think there are four or five people with my name.

PHE- How has life in Mali changed since the photographs we see in your exhibition to today?

MS- The country has changed a lot since the 1960s. Now people prefer to dress in clothes from Mali because the cotton industry is very strong and important. Before, people preferred European clothes, but now people are going back to traditional dress. Young people still prefer Western clothes. Young people are the ones who change the world, not old men.

In the 1960s, girls would sneak out of their houses to go dance. They would put something in their father’s glass of water so he would sleep and not notice when they left the house. Mothers were always the girls’ accomplices, and they were the ones who opened the door for them when they came home in the morning. When the girls finished their studies, fathers were obligated to throw them a party. That’s how the old men became convinced that dancing wasn’t so bad or horrible.

PHE- It seems impossible that in such a long career there haven’t been difficult moments…

MS- I haven’t had many problems in my professional life. People coming out of my studio almost always leave happy, although there’s always one that’s more difficult to photograph, but without causing too many problems.

I did have some problems with the military since I also took photos of the coup. I think it was necessary to portray that moment. I was scared I might lose my life because I wasn’t a journalist, so I wasn’t authorized to take photos.

I still have those negatives. I have photos of militiamen with their rifles. I also photographed the coup in 1968, since I knew the soldiers for having done my military service with them, and they called me to take photographs. But at one moment the General came over to me and asked, “What are you doing here?” I said, “I’m taking photos.” The other soldiers were afraid and hid. The General got really angry and wanted to confiscate my film. They took me to the police station, but fortunately I found a friend there and we talked for a while as friends. I stayed there until five in the afternoon, and the General finally forgot all about it so I could take my film with me. The guy who arrested me had a bazooka in his car, and I was a little afraid, but luckily there weren’t any problems.

PHE- Now you have a solo exhibition at Oliva Arauna Gallery (2009), and your work forms part of the collective exhibit The 1970s. Photography and Everyday Life. How do you feel?

MS- I’m very happy to have an exhibition at Oliva Orauna Gallery (2009) and form part of the collective exhibit The 1970s. Photography and Everyday Life. I couldn’t sleep the night before the opening, but at times I did have some very good dreams. It seemed like I could touch the sky with my fingers. After this, I think I should keep on working much more and even better.

ASX CHANNEL: Malick Sidibé

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow ASX on Twitter.

For inquiries, please contact American Suburb X at: info@americansuburbx.com.

(All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher.)