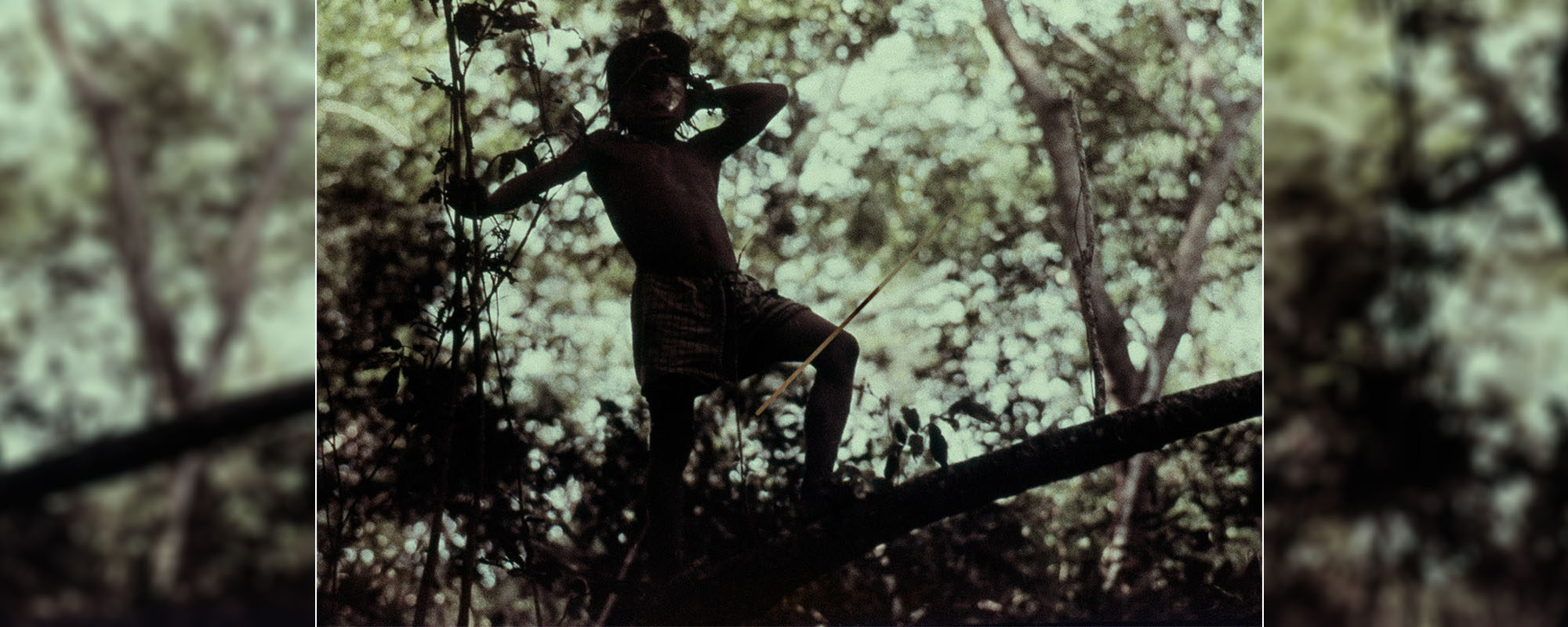

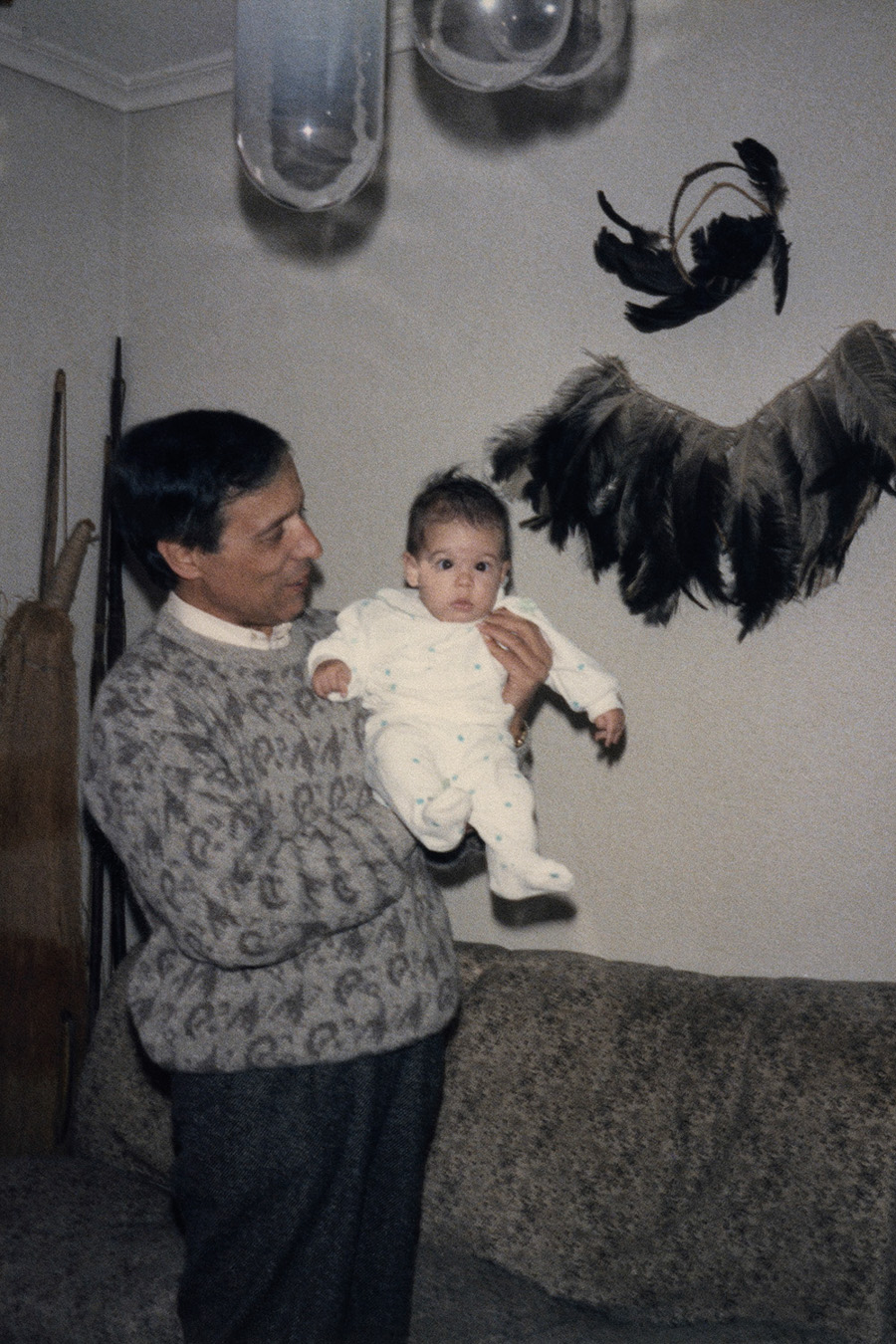

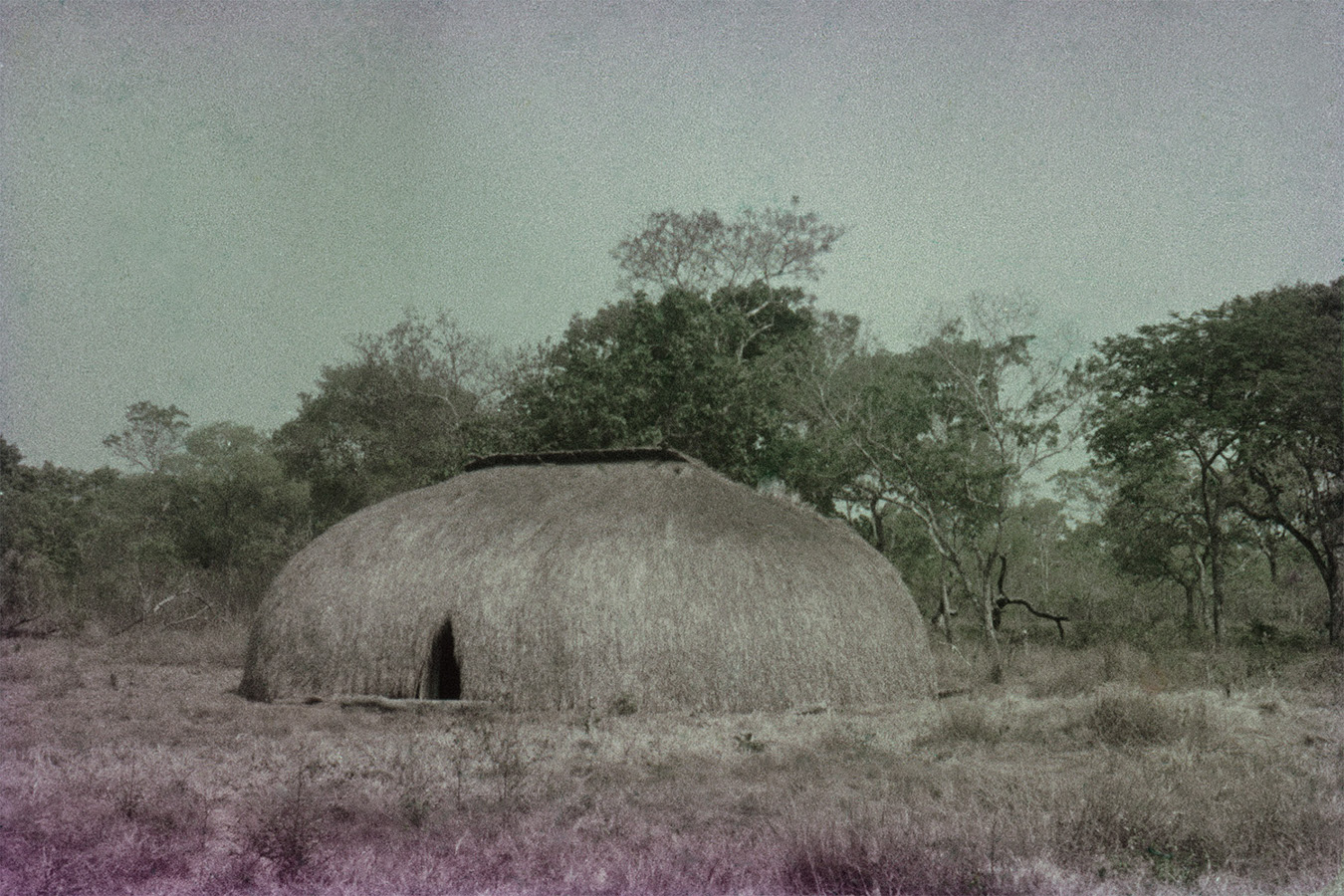

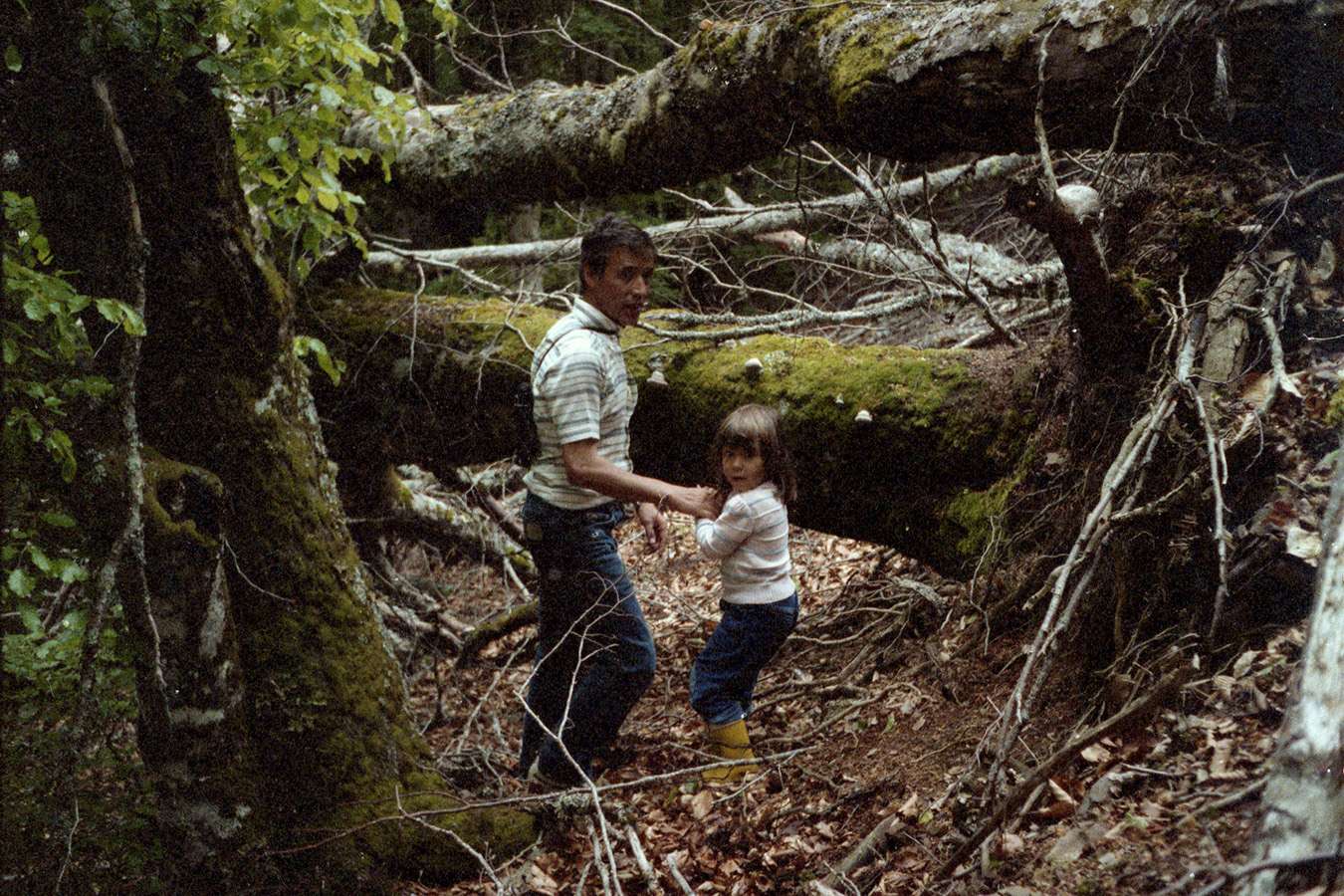

Geographies, histories, feelings, and representations are often interwoven in narrative tapestries, though the patterns created by their threads don’t always yield a unifying image. Raquel Bravo’s Mato Grosso opens with a man’s silhouette, the artist’s father, followed by several shots of dense foliage. How this man’s story relates to these landscapes will slowly unravel through an interplay of images framed within a minimalistic structure. One set of photographs – from a personal archive made in Brazil during the 60s and 70s – is put in dialogue with Bravo’s family photographs from Spain in the 80s and 90s. In addition, there are a handful of double spreads with contemporary photos that add symbolic currency to the sequence. The most stimulating one pairs an old camera with a chalice, hinting at the two most significant factors determining the book’s course of events.

“One of the book’s pleasures is how the narrative unfolds like a mystery novel, strategically disclosing specific facts about the images to increase our motivation to look further and closer. Therefore, if you want to experience these revelations for yourself, I suggest you stop reading here.”

The family photographs were culled from albums carefully put together by Bravo’s mother. A few short texts (in Spanish and English) inform us piecemeal on the particularities of the story, describing the effects her mother desired when making the albums, which underlines the influence of photography in portraying ideas of familial happiness and cohesion. Later in her life, this very process of image selection and organization instigates Bravo to question her biography, particularly concerning the image archive of his father, who passed away when she was very young. One of the book’s pleasures is how the narrative unfolds like a mystery novel, strategically disclosing specific facts about the images to increase our motivation to look further and closer. Therefore, if you want to experience these revelations for yourself, I suggest you stop reading here.

Bravo had to make peace with the tragic absence of his father and with who he was before she – forgive the quip – entered the picture: a Salesian missionary tasked with evangelizing populations of Bororos, Karajás y Xavantes over seven years in the homonymous state of the title. The seemingly disinterested deeds of the religious company were tied with political and economic objectives in a calculated association between the governments of Brazil and Spain. The book briefly explains how religion was instrumentalized for gains far from spiritual, providing enough context to decipher what we see. This interpretive dynamic becomes a poignant example of how difficult it is to gauge cultural and moral values from the mere act of looking at photographs. The way Bravo posits her memories of his father as a myth, emphasizing the impact his stories and artifacts had on her, contrasts with the more tangible reality of his photographic archive of indigenous portraits and the documentation of rituals, creating a fascinating parable of how different narrative inflections define our sense of self.

“This interpretive dynamic becomes a poignant example of how difficult it is to gauge cultural and moral values from the mere act of looking at photographs.”

Despite being foreign to both cultures, I find it curious that I’m more captivated by the family photographs than the ‘ethnographic’ ones, forcing myself to pay closer attention to the latter set. While none of them are captioned, I feel I have most of the codes to read the family photographs, but I would need copious amounts of information to reach the same level of understanding for the ones of Brazil (a subtle reminder of our lack of awareness of how we know what we know). When we reach the end, it is unclear whether this is a book about secrets and past lives or one about rituals, families, and the gestures we rely on to represent ourselves. What is clear is that the book proposes a reflection on the changing nature of evidence that at some point seemed to have a ‘fixed’ meaning. As material culture, photographs are convenient objects to reshuffle in order to support or suppress specific ideas. With this work, Bravo seems intent on contesting the belief that we can clearly define who the villains of History are. Plenty of controversial subjects are at hand here, but if Mato Grosso teaches us anything, it’s that there are always real people behind big concepts such as Colonialism, Christianity, and Liberalism, and whose stories constitute the entire grayscale of morality.

Mato Grosso is one of those complex books in which separating and classifying its interconnected strands is less important than the experience we have when flipping through its pages. Thoughtful design choices are deployed here to allow an unobtrusive evaluation of images, dispensing the vanities that books with archival photographs have become so fond of using. While the density of the closing texts clashes slightly in tone with the openness of the images, it also answers a few questions that I believe are necessary for a better understanding of the narrative. Bravo’s book – at the risk of sounding obvious – suggests that our lives are mysteriously interconnected, and our actions, independently of our intentions, can affect others in ways that are not always easy to predict.

Raquel Bravo

Fuego Books

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Arturo Soto. Images @ Raquel Bravo.)