When my father died six months after being admitted to hospital following a series of strokes, he was no longer the person I remembered. Brilliant, but highly strung and often difficult, the damage to his neural structures had transformed him into someone different – a gracious and endlessly patient man whose stroke-induced anosognosia left him blessedly unaware of his own deteriorating condition. After he had gone, what I experienced was not the sharp stab of grief but something different, the dull ache of a wound that had already begun to heal over. The person my father had been was gone long before the moment of his death, and committing him to memory was a slow, attenuated process, everything I recalled of my life with him irrevocably shaped by my brief experience of the gentle stranger who had taken his place.

We often speak of loss and trauma, memory and grief, as though they exist as points on a smooth continuum – the process of mourning staged as a narrative that begins with death and ends with reminiscence. But sometimes, circumstances pry the two apart. Remembering, then, becomes a more deliberate act of filling in an outline that’s been blurred by the passage of time. Not an act of mourning or recollection, but one of remaking, of unforgetting.

“Objects are malleable things – mutely concrete, or freighted with almost unbearable significance. Watkins’ photographs share this equivocality, wavering between documents and invocations.”

Peter Watkins’ mother took her own life when he was eight years old – too young to be confronted with questions of mortality, or to understand that death for some, is a matter of choice rather than circumstance. By the time he began working on The Unforgetting in 2011, the trauma he’d experienced as a child had long since been replaced by a handful of blunt facts and whispered eulogies. In place of clear memories, all that Watkins knew of his mother was contained in the few possessions that she’d left behind. These objects – carefully preserved by his grandmother – were the starting point for the work.

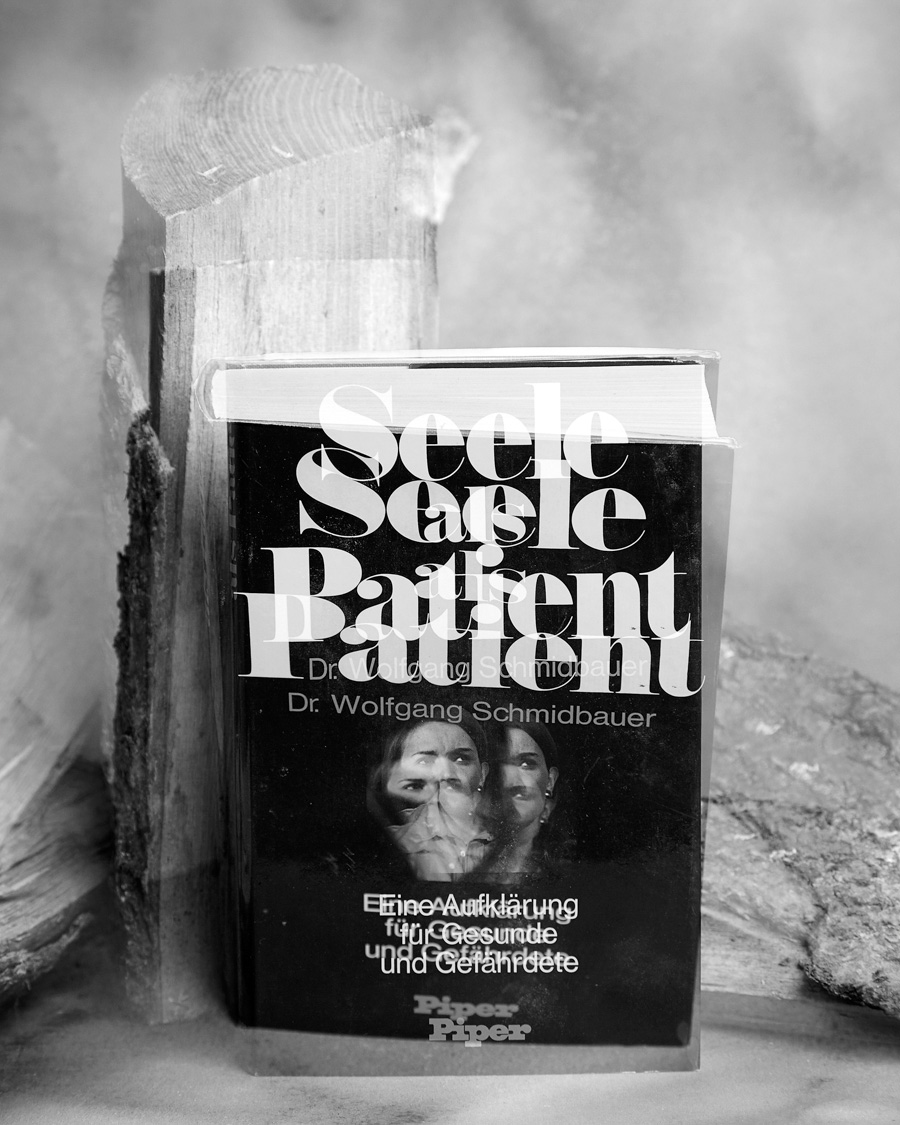

Objects are malleable things – mutely concrete, or freighted with almost unbearable significance. Watkins’ photographs share this equivocality, wavering between documents and invocations – conditioned, in the same way that memory is, by sensory cues like sound and touch, but also possessed of the intensely focused, almost hermetic objectivity of reproductions in a museum inventory. As individual images, there’s something totemic about them – captivating, but self-contained, opaque to the viewer, and often to Watkins himself. ‘What I’ve made is an abstraction’, he remarks, ‘it doesn’t capture the essence of my mother … but looks at that which can’t be grasped’. As fragments of an elusive whole, what they reveal collectively is not truth, but a sense of the contingency that often confronts us in the search for it.

“There are no moments captured in The Unforgetting, only a profound sense of stillness, and a conviction that the subject of every photograph in the book will go on existing exactly as it is, long after the photographer has departed.”

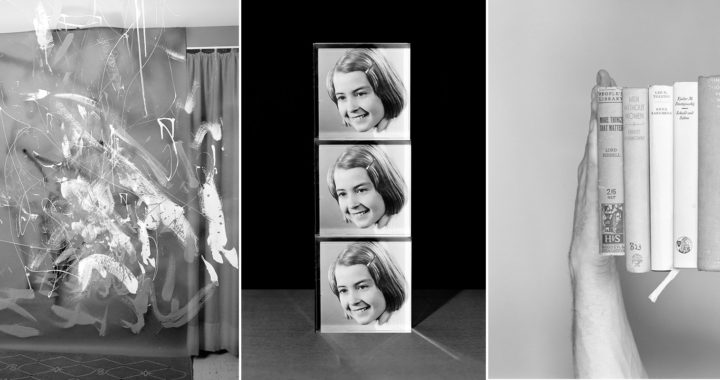

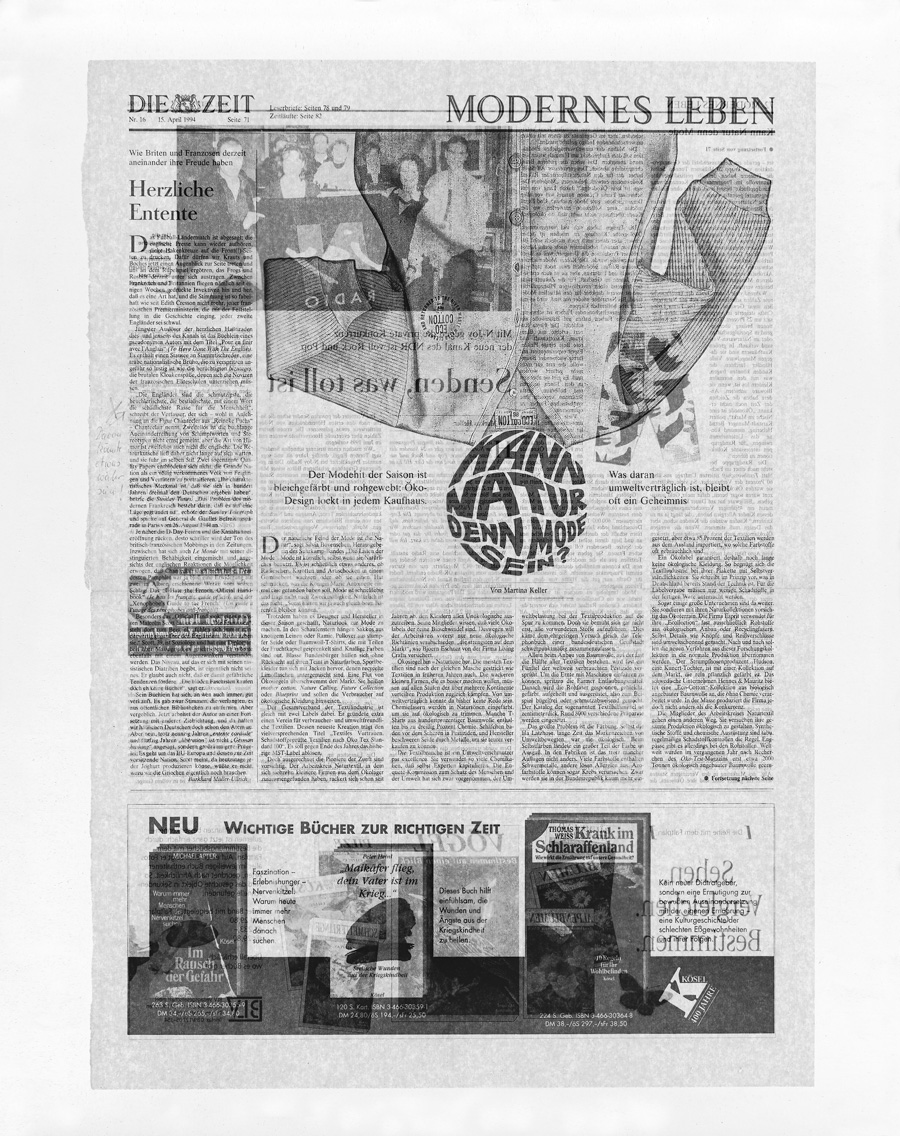

Apart from a single self-portrait, none of Watkins’ images – still-lifes, interiors, and the odd close-cropped landscape – give any clue about the time of their making. There are no moments captured in The Unforgetting, only a profound sense of stillness, and a conviction that the subject of every photograph in the book will go on existing exactly as it is, long after the photographer has departed. The overwhelming feeling is not one of nostalgia, but of anachronism – of a world locked into an unspecified past.

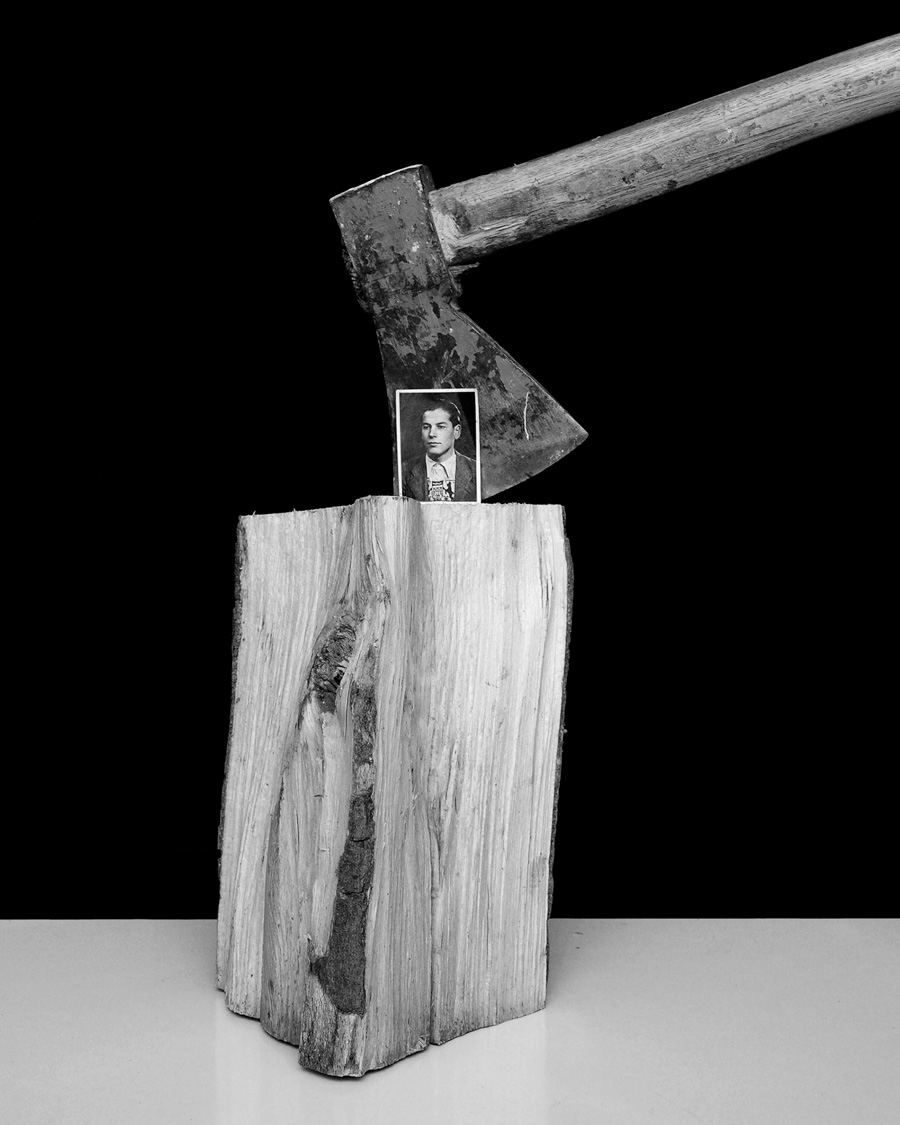

This sense of the ineffable is most tangible in Watkins’ still life images. Shot against a black studio backdrop, the arrangements of photographs, books, and other objects appear to float, ungrounded in time and space, present but distant. If the still life is a way of making objects speak, Watkins’ images transform this language into a kind of aphasia, acknowledging their significance without attempting to resolve the how or the why of it. And while his photographs bring a temporary dignity to these things, they also suggest that such talismans are insensate objects after all, their value determined by nothing more than the importance we assign to them.

If I’ve given the impression that all of this adds up to a great sadness, it doesn’t. The Unforgetting is neither a eulogy nor a lament. Of all the recurring motifs in the work, the one that stands out mostly clearly is wood – in the form of living plants, wooden structures, and timber: sawn, splintered, and stacked. Wood is a strangely immortal substance – transformed by death into a monument to the living thing that it once was. It serves here as a kind of metaphor for the photograph itself as a measure of both presence and absence – not a way of marking the schism between life and death, but of opening up a space for them to coexist.

Peter Watkins

The Unforgetting

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Eugenie Shinkle. Images @ Peter Watkins.)