The 2008 Pixar film WALL-E follows the story of a lone maintenance robot – earth’s only remaining inhabitant, the human population having long since decamped to giant intergalactic spaceships. WALL-E spends his days compacting trash into cubes and stacking it up into pyramids, mountains, and cities – the sole architect of planet earth’s new landscape.

The idea that humanity’s signature and its legacy will be composed of garbage is not so far from the truth. It’s said that the geological stratum that marks the Anthropocene era will consist almost entirely of concrete and plastic: future earthlings seeking the traces of their ancestors will have to dig their way a through a thick layer of polymerised crude oil and paving slabs.

“In Western culture we understand a landscape both as a physical place, and a representation of a physical place – three dimensions translated into two. Both forms are reliant on the idea of a boundary – the first, on invisible political demarcations separating one tract of land from another, the second, on pictorial boundaries set out by the historically persistent framework of linear perspective.”

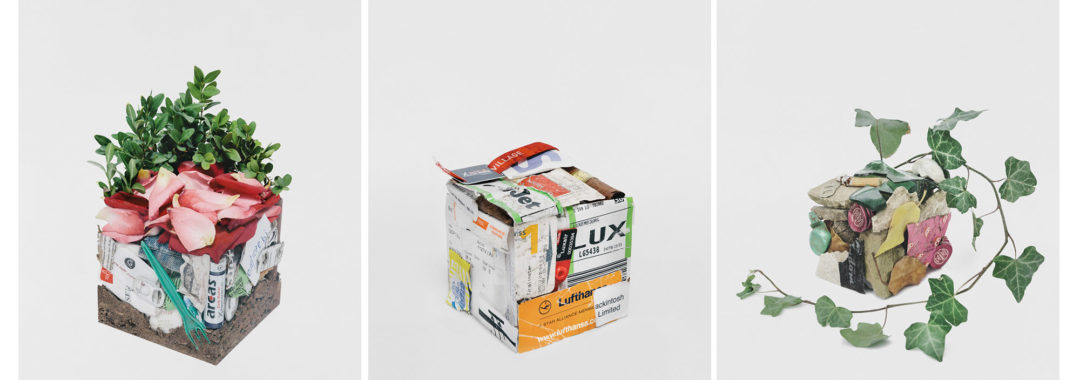

Boris Loder’s Particles is a kind of archaeology of the immanent – the imagining of a future landscape latent in the present. Loder used the city of Luxembourg as a test case, but he didn’t take many photographs of the place itself. Instead, he collected objects from various sites around the city and took them back to his studio, where he packed them carefully into 10-centimetre square plexiglass cubes. The resulting constructions were then photographed, and the silhouette of the plexiglass edited out in postproduction. The result is a series of cubical constructions held together as if by magic.

Part sculpture, part still-life, Loder’s constructions resemble WALL-E’s little blocks of compacted garbage. In fact, this is what they are. The materials that make up each cube are roughly depictive of the places from which they were harvested; most of these materials consist of human-made waste. An abandoned house in Hollerich – an area known for drug use and prostitution – offers up a bounty of syringes and broken glass. A playground yields flower petals, drinking straws and sand. From other sites, Loder has collected bottle caps, cigarette butts, scraps of paper, gravel, fragments of tile and rebar, snippets of plant life. But the primary components of most of the cubes are concrete and plastic.

This deft compaction of the landscape’s components into ingots of trash is also an ingenious unpacking of the notion of landscape itself. In Western culture we understand a landscape both as a physical place, and a representation of a physical place – three dimensions translated into two. Both forms are reliant on the idea of a boundary – the first, on invisible political demarcations separating one tract of land from another, the second, on pictorial boundaries set out by the historically persistent framework of linear perspective.

“Loder’s constructions may appear simple, even whimsical, but they subvert conventional ideas of landscape in a really clever way.”

Loder’s constructions may appear simple, even whimsical, but they subvert conventional ideas of landscape in a really clever way. Apart from a small image of each site in an appendix at the back of the book, Particles doesn’t include any landscape photographs – two-dimensional windows onto three dimensional spaces. Instead, the images that make up the main body of the work show us a series of cubes – three dimensional objects, reduced by the photograph to orthographic projections. Each photograph, in other words, is a two-dimensional rendering of a three-dimensional construct held together by an invisible boundary – a landscape by any other name.

Particles is a smart summation of the processes of boundary-making and representation by which landscapes come into being. It does not – as is so often the case with landscape photography – attempt to link the definition of landscape to ideas of ‘nature’, human-altered or otherwise. Millions of years from now, when tectonic shifts have ground our concrete rubble back into dust, and plastic-eating bacteria have chewed their way through the last discarded water bottle, the earth might eventually return to a state that could be called natural – if by that word, we mean something entirely free of human intention and human presence. Fusing landscape’s past and its present to its possible future, Particles demonstrates how profoundly unnatural a construction landscape really is.

Boris Loder

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Eugenie Shinkle. Images @ Boris Loder.)