“Armenia and Its role in the central Caucasus make its geography of special geo-political reference given its access point, along with Azerbaijan and Georgia to both the Caspian and Black seas and their lucrative conditions of speculative petrol potential”.

Yerevan, the Armenian capital is built from several considerations of the volcanic. In one sense, there are the tremulous associations with political and ideological changes of a city that dates as far back to the 8th Century B.C. to consider. Yerevan is one of the longest inhabited and therefore civilized geographies in the world. The walls of its oldest structure, The Erebruni Fortress (translated Fortress of Blood) still stands from the time of its inception in 782 B.C. by the city founder King Argishti I. The fortress overlooks the teaming and historically prosperous Ararat Plain and Aras River and Yerevan as a whole has been made home to numerous changes to the rule of its authority since its beginning.

Yerevan, due to its historical and geographical junction of the steppe region and its economic capital role has attracted the attentions of regional and international interests since its beginning. Historically, it has found itself mired between Iranian, Mongol and Russian interests and has also provided a shield for Armenians fleeing Ottoman persecution from its Western neighbor Turkey. Its historical importance more recently was that of being made a province mandated by Russia and claimed as Soviet territory until it challenged Russian authority 1988. It re-claimed its full independence in 1991. It has existed throughout with a pivotal sense of its borders and its potential to return to autonomous rule.

The second consideration of the volcanic is that Yerevan and many of its architectural and historical sites are crafted from a pink volcanic stone called tuff. Tuff is an igneous rock that is formed from the cooling lava of a volcanic eruption. It has been used since ancient times as a building material as its relatively soft and porous surface could be cut or re-formed with simple tools into large blocks and could be transported with relative ease compared to other natural rock to building sites and outposts. It is found throughout the world and has been used in this manner by a wide range of cultures. The rock itself differs in the color of appearance, but the tuff local to Yerevan maintains a pinkish hue that informs the city’s nickname “The Pink City”. This moniker has been adopted for the way in which the sun glints off the local stone casting the many buildings who have been built with its material into a pinkish glow. Some of the earliest architectural points of interest in the city are made from the material and it adorns most of the earlier important cultural sites such as the Erebruni Fortress and notably the Republic Square.

Yerevan is again experiencing a change due to the increased economics of the region. Armenia and Its role in the central Caucasus make its geography of special geo-political reference given its access point, along with Azerbaijan and Georgia to both the Caspian and Black seas and their lucrative conditions of speculative petrol potential. Heavy investment has given the local authority of Yerevan the capacity to re-scope the city into a larger capital with contemporary interests aimed at tourism and the establishment of banking and investment. As money flows into the capital, vast transformations have swept through the city, notably the large amounts of construction and building works that have been erected or are in transit to completion. The third volcanic notion here is progress and capital. Since 2000, the capital has seen vast changes to both its infrastructure and its architectural heritage. Many former Soviet buildings, including much the Soviet housing in Yerevan have been razed to make room for newer, more modern high-rise flats within the city. Though a number of important UNESCO-oriented Soviet architectural sites and details remain, many of the common or unexceptional buildings are lost to history.

“Many former Soviet buildings, including much the Soviet housing in Yerevan have been razed to make room for newer, more modern high-rise flats within the city. Though a number of important UNESCO-oriented Soviet architectural sites and details remain, many of the common or unexceptional buildings are lost to history”.

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg’s fascination with exotic culture and its photographic example have the merits on one hand of being about seeing “otherness” for all its implied quantity of term, but is also about as a net positive, the documentation of “otherness” before loss or change can occur. She has photographed widely in the Middle East and Asia Minor. Her work is just now being examined for its dexterity of purpose, genuine elegance and spectacular technical form. Yerevan 1996/1997 (MACK) is a small, but well-timed book. It assesses a small look at the Armenian capital before the rise to progress that has swept through the city resulting in a loss of its Soviet ghosts since year 2000.

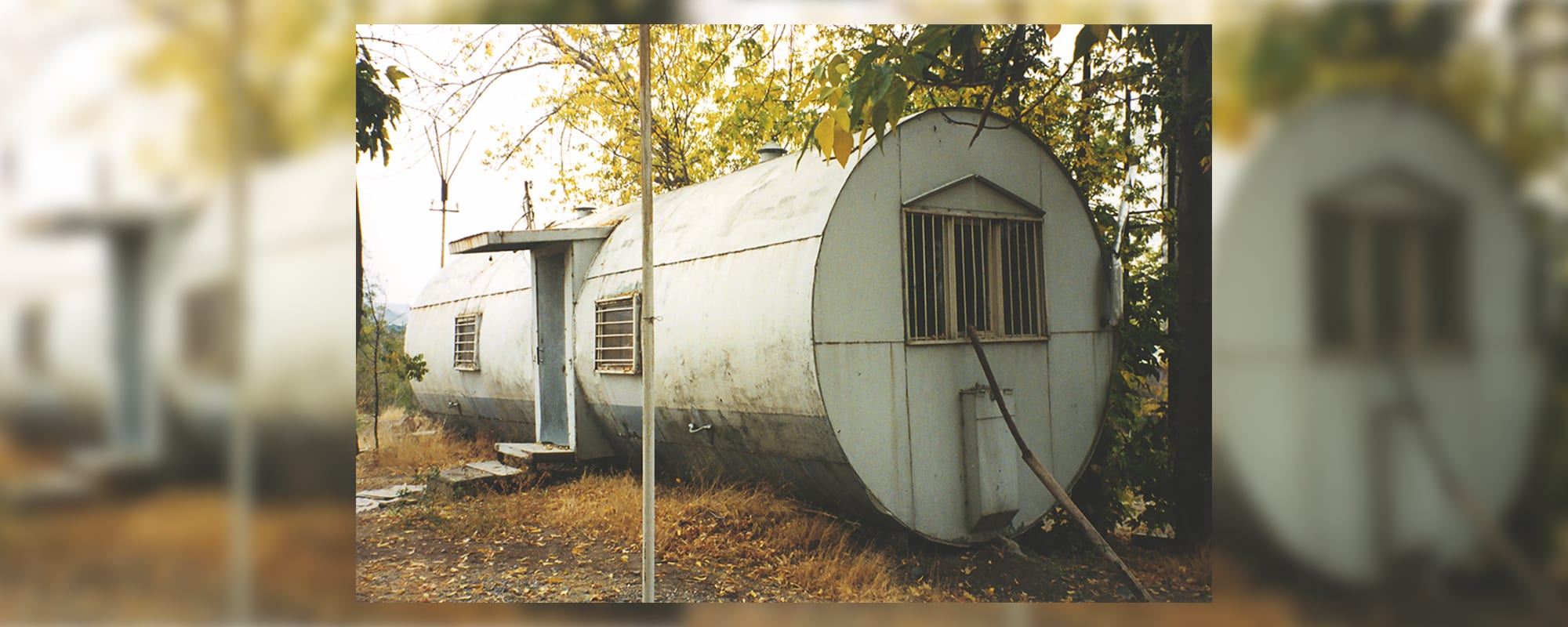

Though the book exceeds in not being strictly about Soviet Architecture per se, with its implied constructivism or irrationally conditioned brutality, the work is however about place in the hinterland of time between the shifting scope of Soviet ideology and Armenian independence. Within, the city itself still bears many of the hallmarks of Soviet diktat of social programming from housing to lack of common financial access and the general fugue state that occurs between two opposing goal posts of change is evident-corrosive and corrugated metal fruit stands and tinman auto repair sheds litter the terrain along with a cast of vernacular architectural vestigial tails such as the “Best Friends Air tickets” tobacco hut and the ever-precarious tramcar bridge over the rushing rapids of the Aras River. The obligatory Soviet bus stop does make an appearance, but it is short and its character completely in-line with the rest of the images in the book.

What is makes the book really exceptional is its design and Schulz-Dornburg’s more casual attempt at image-making reflected within. As opposed to her larger opus The Land In-Between (MACK, 2018), Yerevan 1996/1997 is a smaller, less grand attempt to think through the indexicality of the photographic moment. Yerevan, or the image of it, is arrested here from a very particular moment and corroborates through the relaxed and diminutive design the notion of passing comment. The less formal concerns of larger cameras or larger conceptual frameworks promotes the condition that thee image have a vernacular use, a snapshot familiarity that is unconcerned with the pretense of artistic affair.

The small size of the book and the images themselves “pasted” to an Armenian school book remind the viewer of what instantaneous or quick 35mm images can look like if set to the correct size for viewing, nostalgic dimensions or not. It is as if these images came back developed in their paper envelope from the local drug store kiosk in Yerevan and their 4×6 inch size matriculates their aims, with their “scrapbooking” into an old educational book a point that reveals their potential for a more universal reading.

“The small size of the book and the images themselves “pasted” to an Armenian school book remind the viewer of what instantaneous or quick 35mm images can look like if set to the correct size for viewing, nostalgic dimensions or not. It is as if these images came back developed in their paper envelope from the local drug store kiosk in Yerevan and their 4×6 inch size matriculates their aims, with their “scrapbooking”

The repetition within the work of “The Twins”-the two large housing units with circular geometric windows that Schulz-Dornburg photographs from interior and exterior positions of elevation concern her fascination with the formal, but also how “to see” architecture with limited technical possibility. You will note that she takes a similar attitude to the tram bridge that crosses the Aras River. Here she approaches the vernacular metal passageway with some trepidation and curiosity photographing the yellow exterior in frame one, perhaps two meters from gaining access. In frame two, she photographs the river from the window of the tramcar from an adjunct position and in frame three of the sequence we see the tramcar bridge from further away, but on the same bank of the river from which she shot frames one and two. It is as if she did not make the crossing, herself filled with doubt, yet she needed by the strict accord of her fascination to photograph the interior.

Further throughout the book, you see something fairly absent in most of her work-people! Though the immovable and architectural images remain her focus, on occasion you will see a face looking out a window, find empathy with the auto repair local and most (in her case) unnervingly find yourself gazing at a little boy on a tight rope-a picture that recalls the Parisian humanist tradition of Izis or Robert Doisneau. It is compelling to have these images of humans grace her book sparingly. Schulz-Dornburg stands at a strange precipice with her work as it is generally speaking completely about culture and the remnants of human civilizations. Conversely, most of her work refuses to employ people within the frame perhaps out of respect, but also likely out of formal interests. The few times that people enter the book, they serve as reminders of place and are considered the constituents of concern fathomed between the shifting tides of history and the visible architectural symbols that define their habitat.

Yerevan 1996/1997 is not about defining an artist’s career in the same manner that The Land In-Between did. It is a small book, priced economically that explores but one of the many presumed projects that Schulz-Dornburg likely has in her archives that should be seen in a wider remit than simply being a photography book. The material applies to historical enthusiasts as well as photographic and I am positive that the book fits on the shelves of architectural offices or libraries just as easily as photographic centers. It is a small book that crosses the potential to be examined by audiences outside of our own and we should see that also as a net plus. I think the design, with its mix of collaged or aggregated Armenian vernacular makes the book quite sweet. The letter in the back to Schulz-Dornburg’s daughter also emphasizes the personal and makes the book more of a caring letter to a family member-an insight into a loved one’s past, a fragment for contemplation and interior knowledge. Highly Recommended.

Soundtrack: Clock DVA-Buried Dreams

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Brad Feuerhelm. Images @ Ursula Schulz-Dornburg.)