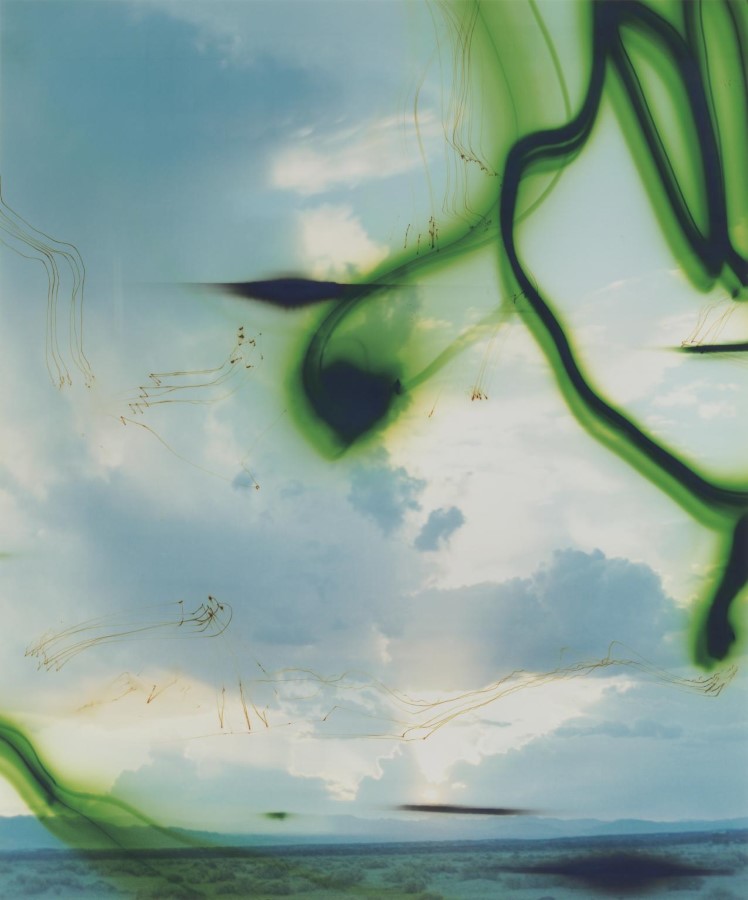

In Flight Astro (II), 2010 @ Wolfgang Tillmans

I have also been greatly inspired by magazines and by the immediacy that a magazine can have on the viewer. You can find it anywhere, it can travel much easier than an exhibition. So, the potential of the printed page, just like the potential of the photocopy as a venue for art, has been with me from the start.

By Wolfgang Tillmans, Lecture, Royal Academy of Arts, London lecture, February 22, 2011

Last Autumn I did a talk in New York at the ICP [International Center of Photography] and I thought how am I going to do this one, and I realized that a lot of the audience were just about born when I started working [laughs]. Suddenly, this sense that I have of the overlook of the development of my work was probably lost to a lot of people in the audience. So, I’m going to do something similar and I’m going to show you a lot of pictures. This is going to be feature film length, but I promise not longer than 90 minutes.

After having experimented with a number of media, from singing in a band to making dresses, to painting, and drawing, I came across a photocopier, the first digital photocopier, in 1986, in a copy shop in my hometown, and realized its great potential of reproducing halftone images with an enlargement of up to 400%. After having worked with different expressive modes, I was totally taken by this potential of a mechanically produced image that didn’t really get touched by me, but was still made by the touch of a button. And yet, out of this industrially produced sheet of A3 paper, a transformation happened into an object that I held with great esteem and great appreciation. That interest in the texture, in the surface of the photographic print, has stayed with me ever since. I’ve been ever since also open to digital printing, at the time when that was not, of course, widely used. But I have, until a couple of years ago, never believed in digital image taking. When I made my first little exhibitions in Hamburg, in 88-89, I realized I needed my own camera to make more pictures that I could then photocopy. And that’s how I really ended up at photography.

Hallenbad Detail, 1995

People occasionally say that I look at everything, that I’m all-consuming eye, and I beg to differ. I think I do not photograph everything, not everything all the time.

At the same time, ‘acid house’ happened and I was, for the first time, part of a youth culture, a movement. And I greatly embraced this liberating music and club life, which was in such stark contrast to the posy-dressy 80s. That particular late 80s, early 90s music scene was so powerful because it was non-hierarchical, all-inclusive, and of course a bit mind-expanding as well [laughs].

Very early on, I recognized the potential of photography speaking about three-dimensional issues. The relationship between photography and sculpture is to me very strong. This photograph is from 91, called Grey Jeans Over a Stair Post, dealing with personal subject matter, not really in a “diaristic” way, but in a general way. I was not talking about somebody’s specific jeans, but was trying to speak about the meaning of clothes, the essential aspects of these membranes that are between our bodies and the world. This photograph is also from 91, and is called Still Life Talbot Rd.. Both types of pictures you just saw – the one of the art historical genre of drapery, and the still life –, are parts of an ongoing interest. They’re not series; I don’t really ever work in a serial mode. I don’t make them in an art historical reference, they’re not meant to be primarily read through art history. Instead, I see that the still lives on window ledges from 400 years ago are there because also those artists have been drawn to the particular situation between inside and outside or that fold of fabric is of a deeper interest and potentially of greater meaning, even though it is so inconsequential and insubstantial. Without referencing art history, I feel that these different genres have come into my work, and that they are there co-existing ever since.

I have also been greatly inspired by magazines and by the immediacy that a magazine can have on the viewer. You can find it anywhere, it can travel much easier than an exhibition. So, the potential of the printed page, just like the potential of the photocopy as a venue for art, has been with me from the start. I approached i-D magazine, which at the time was an alternative non-commercial journal, documenting urban youth culture, and started to take photographs for them. I realized that the fashion pages in these magazines are really the only pages where you can publish pictures that have no particular agenda. From the mid 90s onwards, fashion magazines have become completely and utterly linked to the advertisers. […] But in these days I did actually style these photographs, I chose the clothes and made my observations or comments on, for example, the depiction of genders in the media. For example, that toplessness in women is not equal toplessness in men (Lutz & Alex holding cock, 1992); to get an equality it should really have a bottomless in men. Simultaneously, I carried on exhibiting these pictures and have been very at ease about them existing in magazines, as well as on gallery walls. That has not been an easy position to take and, for a long time, my practice was being read in a hierarchical way, as if no artist could deliberately choose to publish in magazines. It was always seen as he is a magazine photographer who then moved into art. I find that interesting that that is continuously the case: that applied arts seemingly preclude the fine arts practice.

Those 90s were… [laughs] those 90s!… I mean, I was very enthusiastic and excited about exploring what one would cover under the umbrella of the term identity, and how it is a fractured one; how it is not one single entity, but it is composed out of different aspects, of different layers. […] For example, the use of military clothes (Lutz, Alex, Suzanne & Christoph on beach (orange), 1993), which have been altered in their meanings. All of this also loosely circling around the politics of the body, and trying to show pictures of people not afraid of their bodies; a free and playful use of their bodies and sexuality, not in an exploitative, but in an equal and participatory way.

The portrait is also something that stays with me and that I would find difficult or problematic if I got tired of it, because it is an exercise in alertness where no recipe can help. If you go into the situation with a sense of security, then the photograph will look exactly like that.

This is a view of the recreation of one of my first exhibitions, which I also consider my first show after the photocopy works of the late 80s. This was in 93, at Daniel Buchholz gallery, in Cologne. To show the equivalents between a hand-printed fine photographic print that I made with my own hands, and a magazine page which has been printed for 30 000 copies, but which had been laid out and designed by me, I showed these side by side: the prints carefully taped, so one can remove the tape, and the magazine pages pinned, because the tape would tear the different paper. All of this has been about the purity of the objects. To not frame them has been really about showing it in the way it would lie in my hands in front of me. This way of installing doesn’t speak the language of importance of framing one piece and presenting it on a big white wall.

The portrait is also something that stays with me and that I would find difficult or problematic if I got tired of it, because it is an exercise in alertness where no recipe can help. If you go into the situation with a sense of security, then the photograph will look exactly like that. And that is an axiom that I found generally to be true. Photography always lies about what’s in front of the camera, but it never lies about what is behind, it always clearly reveals the intentions that are behind. So, if you are in a portrait situation and you’re not open, you’re just putting the person into a pre-set idea. Then, photography will only speak about that pre-set idea. Allowing and being as prepared as possible for what might happen, while staying open for what chance may come into play, is my way of working. That is hard to maintain because the moment you think you know how it works, the parameters have already changed. This openness is an ongoing challenge, which doesn’t get easier the longer one works. This photograph (Deer Hirsch, 1995), for example, is a good illustration of this correlation of chance and control. […] What looks like a heavily staged photograph has actually been a chance encounter on a beach in Long Island, where there happen to be wild deer. We were feeding our food to the greedy deer [laughs] and, then, when nothing was left, Jochen was gesticulating that there’s nothing left in his hands. I saw that and just said: “hold it”! I just rewound the situation by one second, and took this photograph of an attempted communication between animal and human.

People occasionally say that I look at everything, that I’m all-consuming eye, and I beg to differ. I think I do not photograph everything, not everything all the time. When I have arrived at a picture of something that holds the essence of what that experience, that object or that subject might be, I don’t embark on an entire series, I just rest with that. For example, for some people, my photograph Hallenbad Detail (1995) might contain the smell and remind them of their own experience in a place like that, and that point of connection interests me. […] I still try to photograph every sunset that moves me, however hard that is. Is it possible to take another photograph of this? Is it possible to make something new in the face of potentially completely exhausted subject matter? That challenge continues to excite me: the transformative power of photography, the way you look at things, and the way they will look back.

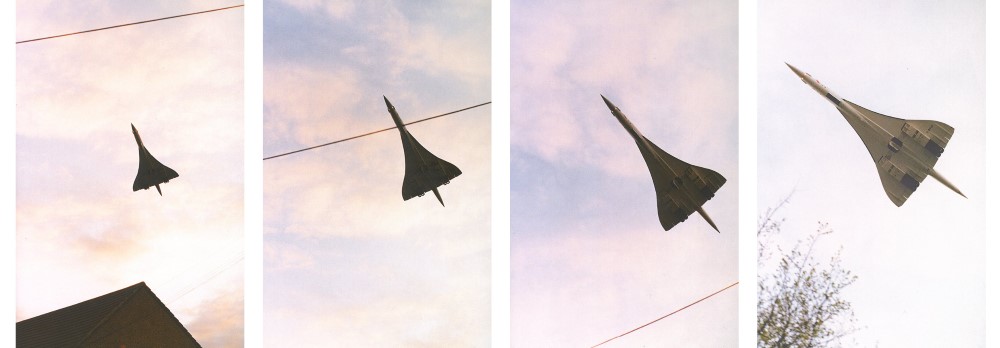

from Concorde @ Wolfgang Tillmans

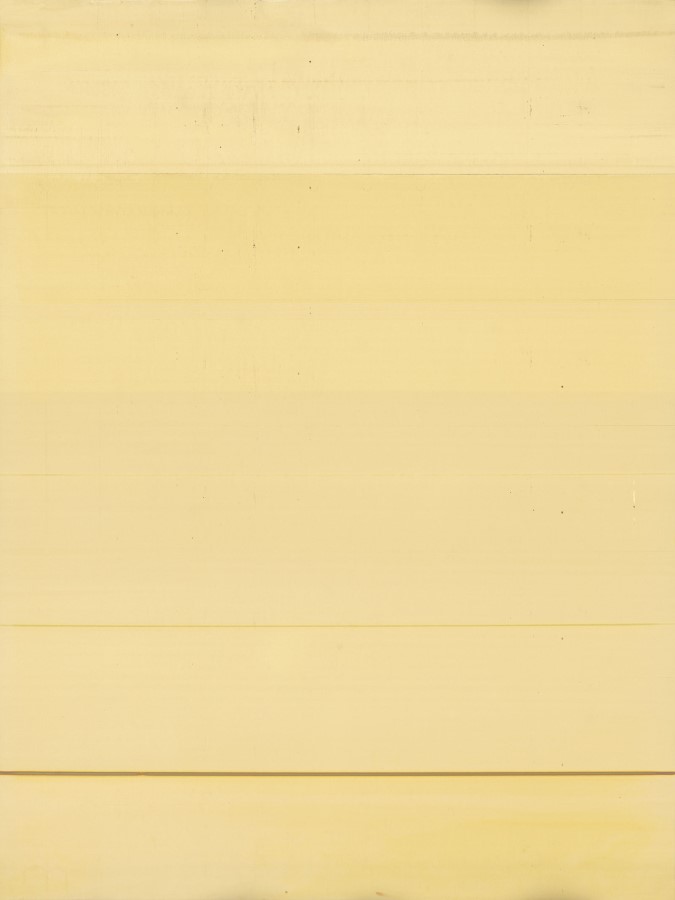

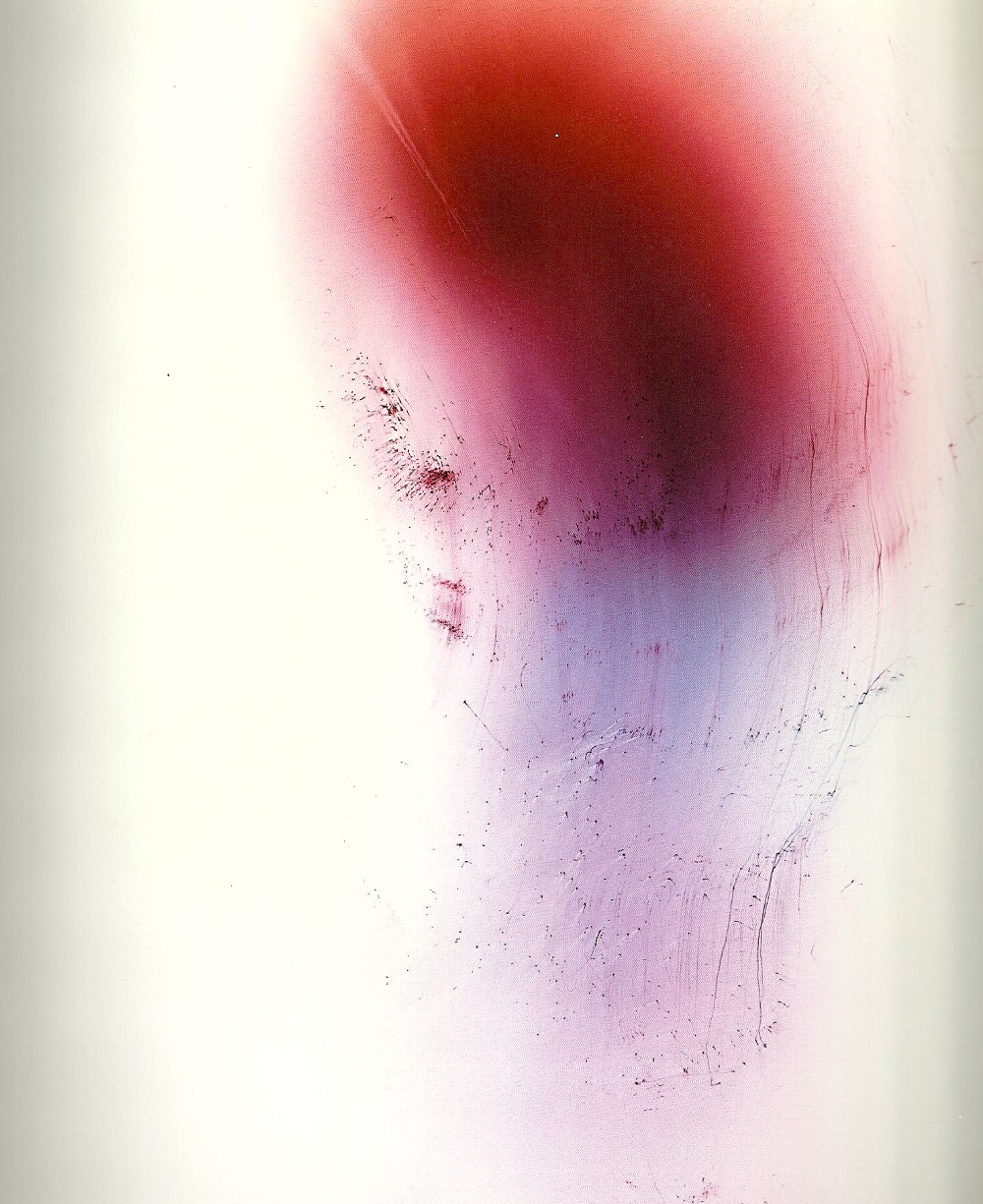

Blushes #28, 2000 @ Wolfgang Tillmans

From 2000 – really from 1998, but more visibly from 2000 – I included work that was not made with a camera, that was non-figurative and pretty much abstract in nature. There was a sense of surprise which I could never quite share, because I felt that abstraction has been within my work from the start, from the early black and white photocopies.

From 2000 – really from 1998, but more visibly from 2000 – I included work that was not made with a camera, that was non-figurative and pretty much abstract in nature. There was a sense of surprise which I could never quite share, because I felt that abstraction has been within my work from the start, from the early black and white photocopies. The work called Concorde, from 97, which first was a book of 64 photographs and, shortly after, a grid of 56 photographs of the supersonic airliner which had intrigued me for years because, at the time, it was the last and only thing left from the space age that was fully functioning in the way it was originally designed. Other things from the 60s that were made from this belief of a better future through technology had been defunct, had been abandoned, or had to be repaired three times over. But Concorde was this icon, this image of overcoming time and space through technology. That straight forward belief was of course no longer available for my generation, and so this really is a work functioning on many levels. It may also be a love story, the work of two nations, and also an abstract piece of 56 colour gradations.

It took me years to finally act on this little seedling of an idea that popped-up occasionally in my head, and that is what I want to address the students present tonight about. I found that it is crucial to take these ideas seriously, ideas that are seemingly unimportant or inconsequential, that don’t feel big. But if they knock on your conscious three times, then it’s usually a good moment to take them seriously and to act on them. Because those things that come up from the subconscious or semi-conscious, and mix with the conscious, those are the things that are truly yours and are not ideas that have been invented, that have been made up. I guess when one talks about art and making art it is by nature language driven. But visual art is not primarily driven by language and there is a dichotomy in that when one is, on the one hand, constantly forced to talk about it, and language seems to favor ideas, and, on the other hand, one also shouldn’t blindly follow any idea that comes to mind. It’s a difficult equilibrium. That’s why I usually find the serial work that is just an idea, and then played out forever and ever again, less interesting, unless it is for a particular reason.

Here’s an example of the Blushes, which is a 24 x 20 inches C-print a color photograph (Blushes #3), which I began making in 2000. […] I never felt a particular allegiance to the camera as such. I love the camera and photography because it can speak so easily, it can communicate so freely, and can be expressive without the weight of expressive gestures that, for example, comes with painting. I found that lack of expressiveness on the surface very liberating, and this allowed me to make pictures that wouldn’t probably be possible for me to make when painted, even though they are painterly in some way. It is really important that they are photographs. The brain instantly connects to them on a realistic level, trying to connect them to reality and removes this sense that each mark has been made by the artist’s hand. Another type of semi-abstract figurative work also emerged in 2000. This one called I Don’t Want To Get Over You (2000) was the centre piece of my Turner Prize presentation in 2000, and, from the year after, the photograph called New Family, give good examples of the co-existence of abstraction and figuration, and abstract elements in figurative pictures.

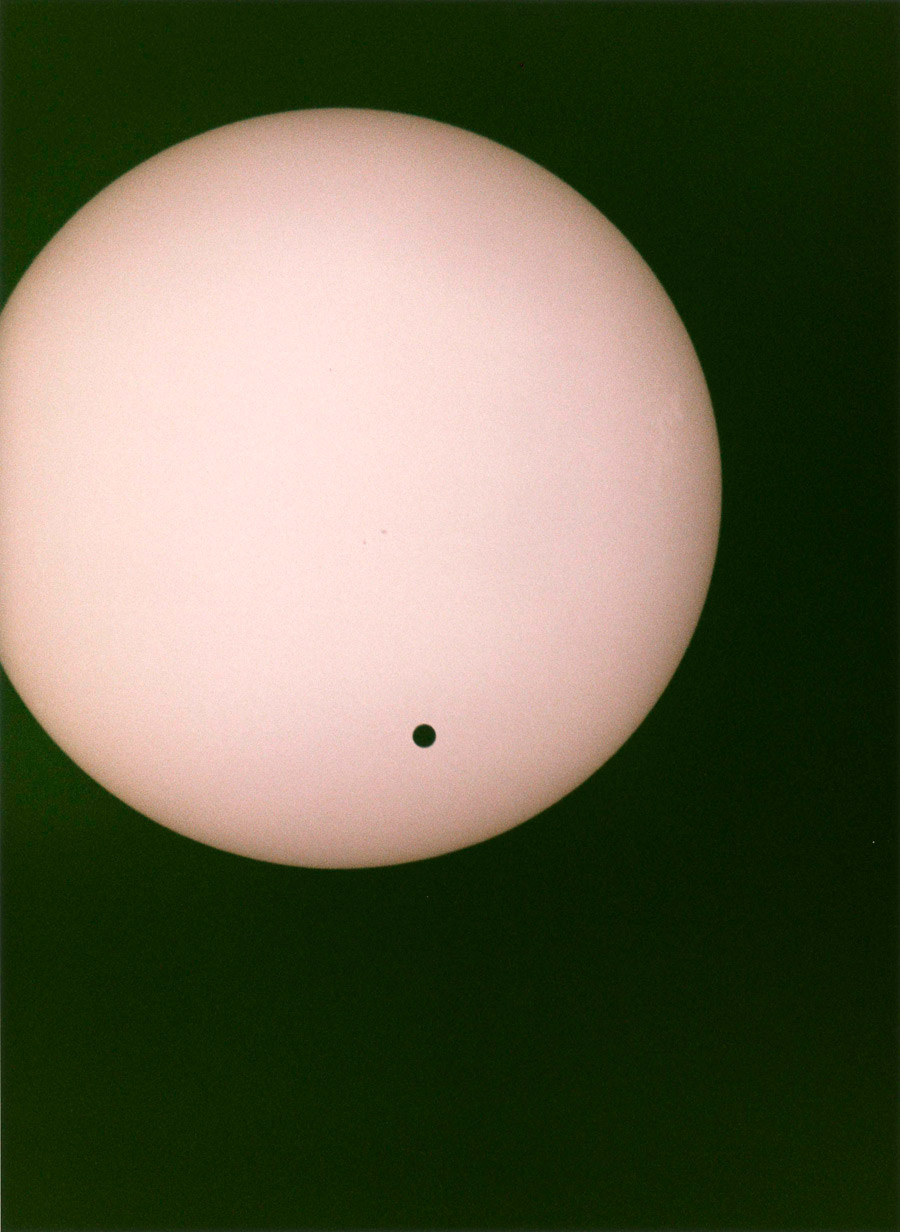

Somehow my visual initiation was as a child through Astronomy, I can’t quite explain… actually, I do know what happen: there was a little book I found in my parents bookshelf, an introduction to Astronomy, and it completely got me hooked until I was 14.

Somehow my visual initiation was as a child through Astronomy, I can’t quite explain… actually, I do know what happen: there was a little book I found in my parents bookshelf, an introduction to Astronomy, and it completely got me hooked until I was 14. That experience of intense observation, of looking at dots of light for hours, I believe has had an important influence on me. And I stayed fondly connected to the subject.[…] When I was like 10-11 years old I knew that when I’d be 36 years old there would be a transit of Venus happening, which is an extremely rare astronomical phenomenon taking place every 128 years and then 8 years after once more and then not for another 128 years. And what happens is that the planet Venus, the Earth, and the Sun are perfectly aligned – just as it happens in a total solar eclipse where Moon, Earth and Sun are perfectly aligned. And then you see the little disk of Venus move over the duration of six hours over the disk of the Sun. So what you here see is: the pink circle is the Sun, the spot is Venus (Venus Transit, 2004). This was of particular importance in Science History, which led actually to the discovery of New Zealand, and Australia by Captain Cook, who went out on a mission to time the entry of Venus and the exit of Venus into the disk of the Sun, compared to the same timing taking place in London, and from the two time keepings one hoped to determine the parallax, and determine the distance of Earth to the Sun. So it was really the only way at the time to locate ourselves in the universe, where we are in relation to what surrounds us. For me that was an extremely moving experience to see, like the mechanics of the solar system right in front of your eye. And the next and only time in our lifetime will be on the 6th of June in the next year, when the second Venus transit of this cycle appears visible, from the Asian, Australian hemisphere.

For years I admired in museums the Spinario subject matter for antique sculptures, usually a young person pulling a splinter from their foot. Because again it is such an universal experience of how everything is of relative importance and if you have a splinter in your foot the entire world around you could collapse, you only want to get that splinter out of your foot. One day I walked into the living room and my boyfriend Anders was completely absorbed trying to remove a splinter from his foot, and this picture (Anders Pulling Splinter from His Foot, 2004) was completely not set up or made in any way in reference to the historical forefathers, but of course stays in direct lineage to it. The interest in paper – in the three-dimensional presence of paper – is something that struck me in 2000/2001, when I realized that really absolutely everything I do is on paper. And I began photographing photographic paper. This was the first, in 2001, which I called Paper Drop, it was a sheet hanging curling on a wall. Five years later, I came back to the subject, then folded paper over onto itself and photographed it with a very shallow depth of field, so there is only the very rim/edge in focus, and everything, in front and behind, it is out of focus and, then, this strange two-dimensional/three-dimensional looking drop shape works emerged.

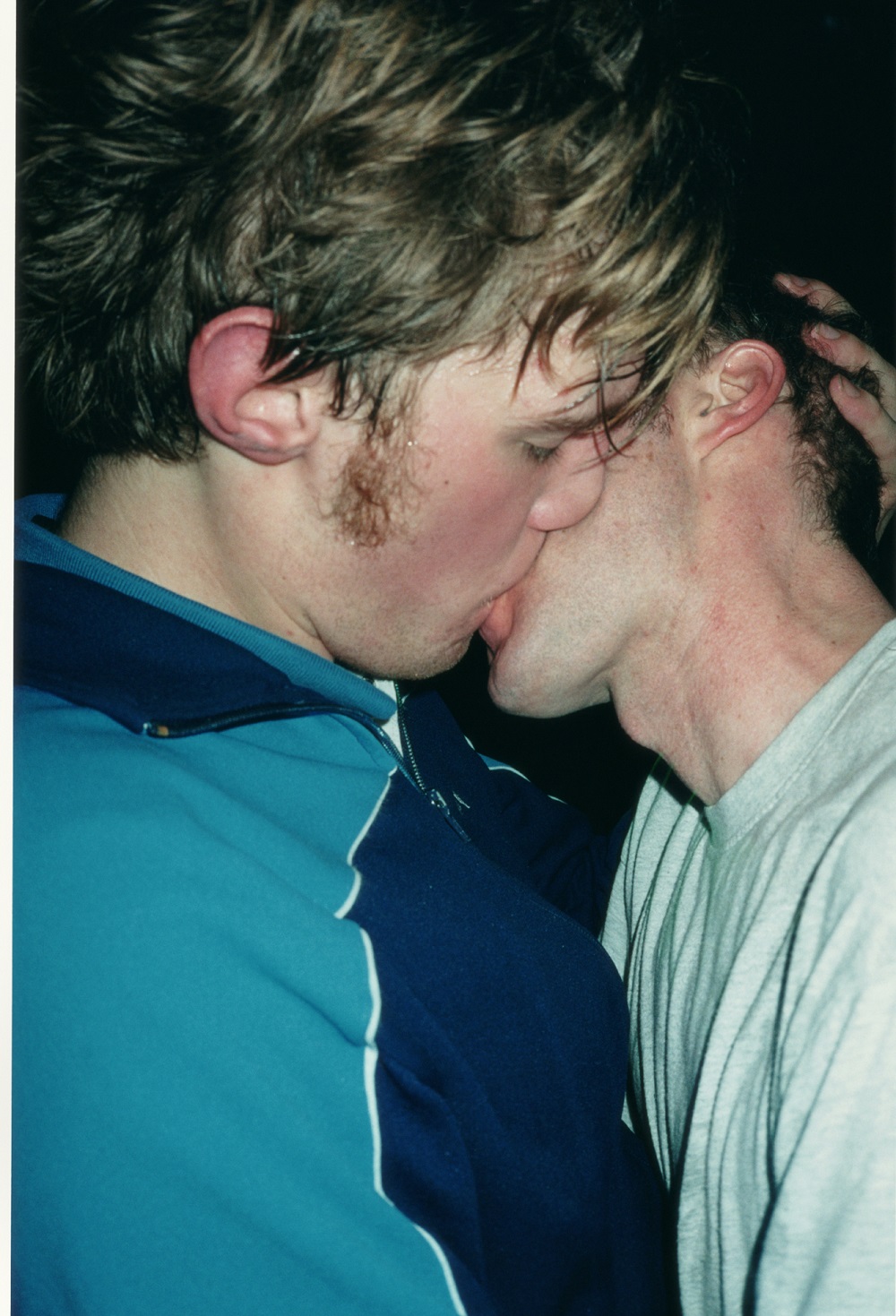

The Cock’s Kiss, 2002 @ Wolfgang Tillmans

Very occasionally I have a moment of seeing a person in a painting, and then feeling compelled to portray, re-portray this person. It’s not really an act of art appropriation, but re-framing the person in the first degree.

Ten years ago, when I last held a talk at the Royal Academy, then in connection with the Apocalypse show, the pictures were shown as analogue slides, and showed of course so much more detail than the digital projector, which is a kind of a nemesis of any artist’s work. It is just interesting how we freely accept lesser quality through technology. We’re all watching Youtube, we’re all watching the films in the worst possible resolution and think this is an advance [laughs]. But anyway these are really actually quite beautiful in real life and they are called Silver, a family begun in 98 and continuing. They are the opposite of the abstract pictures that I make with lights on paper in the dark room, where I use different light sources, manipulate them over light sensitive paper in darkness, and then process the paper normally through the conventional process. These Silver works are actually chemograms, made with wasted chemicals, picking up the dirt from the rollers of machines. They are mechanical pictures. And all I do is set up the parameter surrounding their making, they don’t have my hand involved, and they are usually enlarged to 1,80m x 2,40m.

In 2005, I also made a transition into actually three-dimensional photographs that have been folded or creased either before exposure or after exposure, after processing different modes that lead to different results, again still fully, and 100% photographs, but now again a photograph with no subject, more with an object inserted into them. They become photographs that reject the natural role of depiction because they are things themselves, which is of course the case for all photographs; I’ve seen them always as extremely flat cubes. Here, in the photographs called Lighter, in reference to cigarette lighters that play a role in their making, their emancipation of the role of depiction becomes more fully apparent.

After ten years of primarily exploring the relation of abstraction and figuration, I’ve felt from 2009 a renewed interest in looking at the world. How does the world look like 20 years after I began my career? I have travelled extensively and photographed a great deal with a camera; and also a new type of camera, a new technology has finally allowed the digital camera to be better than film camera. For years and years I’ve been asked “do you photograph digital?”, and I said “what’s the point? A 100 ASA film has 14 megapixels and your camera has 6, so why should I use digital?” [laughs]. I mean, it’s all about resolution. Now the threshold has been crossed and new full format chip cameras allow an exact optical performance like a 35mm camera. They act exactly as my 35mm film camera, but they have a higher resolution, so now that has become for me natural to of course use that, because it is a true advantage that however co-exists with film. This interest in technology it is not only in my own medium but also in the world, looking at things that simply have not been there before.

In 2008, in the preparation for the Venice Biennale where I had a major installation, I travelled to different borders, and I went to Tunisia to the place where the boats of refugees left for the Italian island of Lampedusa, and I travelled to Lampedusa where those boats landed. They of course all arrive in these hardly sea worthy boats that are basically one-way journeys. The Italian authorities don’t send the boats back; they take them out of the water and destroy them on a gigantic ship-graveyard (Lampedusa, 2008). At the Walker Art Gallery, in Liverpool, in 2010, I had an exhibition where I was invited to integrate twelve works that the Art Council Collection had acquired, plus three that I added to the group. I was given carte blanche to move, remove, insert, and combine them with my own work. There was a Flemish tapestry of the same size and I replaced it by Freischwimmer 155, an inkjet print. There were interesting and unexpected relations happening in the room between the presences of the huge steel blue colour and the most of the skies in the old Baroque paintings.

from the Silver installation @ Wolfgang Tillmans

So, sometimes I’m said to be turning everyday subject matter into beautiful things, and I find that a bit uncritical, unless it is connected to that beauty is of course always political, as in it describes what is acceptable or desirable in society.

In 2006, in Los Angeles, the Truth Study Center installation, which has a title a little tongue in cheek, is a response to the polyphony that surrounds us. I also use my work as an amplifier, using the medium to promote causes. I found myself powerless in the light of what happened in the last decade, and often found the newspapers articles commentary much more to the point. So I included them and placed them around. It’s all about different levels of perception and clarity of seeing.

Very occasionally I have a moment of seeing a person in a painting, and then feeling compelled to portray, re-portray this person. It’s not really an act of art appropriation, but re-framing the person in the first degree. […] This photograph (The Cock (Kiss), 2002) of two guys kissing got slashed by a visitor at the Hirshhorn Museum, in Washington. I’m always aware that one should never take things for granted, never take liberties for granted. For hundreds and hundreds of years this was not normal, not acceptable, and this term of acceptable is really what I connect beauty to. So, sometimes I’m said to be turning everyday subject matter into beautiful things, and I find that a bit uncritical, unless it is connected to that beauty is of course always political, as in it describes what is acceptable or desirable in society. That is never fixed, and always needs reaffirming and defending.

Download the PDF

EXPLORE ALL WOLFGANG TILLMANS ON ASX

(All rights reserved. Text & images @ Wolfgang Tillmans.)