It is a description that I would not normally associate with photography books, but Philip Brookman’s Redlands is a real page turner.

By Karin Bareman, ASX, July 2015

It is a description that I would not normally associate with photography books, but Philip Brookman’s Redlands is a real page turner. Within minutes I was gripped by both the visual as well as the textual narrative. The book relates the story of Kip, a young boy growing up with his father in Mexico during the 1960s. His elder sister Addie and his mother are living in Redlands in Southern California. When his mother dies of cancer, Kip and his father return to the US. Throughout the story Kip is curious about the mother he has never really known, but he is strangely reluctant to find out who she really was. At the same time this is the mystery underpinning the entire narrative. Who was his mother in the end? Addie and Kip’s father provide tantalizing hints, but it takes the reader and Kip to the end of the book to find out.

Kip is an anti-hero in many ways. It is his sister Addie who drags him to LA in an attempt to run away from home. Addie also ensures that Kip gets back home safely after that particular adventure. It his girlfriend Angie who shows the initiative when they are living in New York and San Diego. She is the one concerned with practicalities, with finding halfway decent accommodation, with earning a living, with tracing Kip’s family history. When she tracks down the house where Kip’s grandfather used to live, it takes him by surprise. It also nearly paralyses him with indecision and inertia. Angie then leaves Kip behind in New York, as she is fed up with his apathy.

Angie and Addie are Kip’s positive and negative foils. Angie frantically pursues jobs and degrees as she is the only child in a migrant family born legally in the US. She therefore feels the pressure to succeed in life. Addie continually tries to escape her life on the streets and her addiction to drugs, even though they help her deal with her difficult childhood of caring for her mother. Kip simply stands by and stoically observes the people and the action taking place all around him. He later goes on to record it with his camera. The reader-viewer is led to believe that a newspaper cutting inspires him to do so: “Leo (July 23-Aug. 22) Though nothing earth-shattering seems to be going on, take photographs anyhow. This helps you recall what happened today, which will be far more remarkable in the light of memory.”

The title of the book refers to a specific town in Southern California. Initially the reader/viewer assumes this is where all the action will take place. But the town is the setting for merely three chapters in the entire narrative.

The title of the book refers to a specific town in Southern California. Initially the reader/viewer assumes this is where all the action will take place. But the town is the setting for merely three chapters in the entire narrative. As each chapter is set in a different locale and as each chapter is separated by a gap of several years, the photographs positioned in between act as a bridge to cross any temporal and geographical distances. It is faintly reminiscent of the structure adopted by David Nicholls in One Day, where the reader follows the developments in the lives of the protagonists on a particular day year on year, wherever they may find themselves. Choosing a particular locality as the title of the book further reminds me of John Williams’ Butchers Crossing, where the vast majority of the story line is set in a valley in the Colorado Rockies, rather than in the eponymous town. Both Redlands and Butchers Crossing function as literal points of departure for their respective story lines.

While Redlands adopts several literary devices, it also pays homage to a cinematic one. The juxtaposition of the images not only with each other, but also with the text, can be seen as a beautiful example of Eisenstein’s notion of montage. The textual narrative does not function without the visual one nor the other way round. As a result something else, something stronger, emerges. This is an impressive achievement, because the beauty for me in reading lies in that I can conjure up my own images. Many a book has been ruined by being televised or being translated onto the big screen.

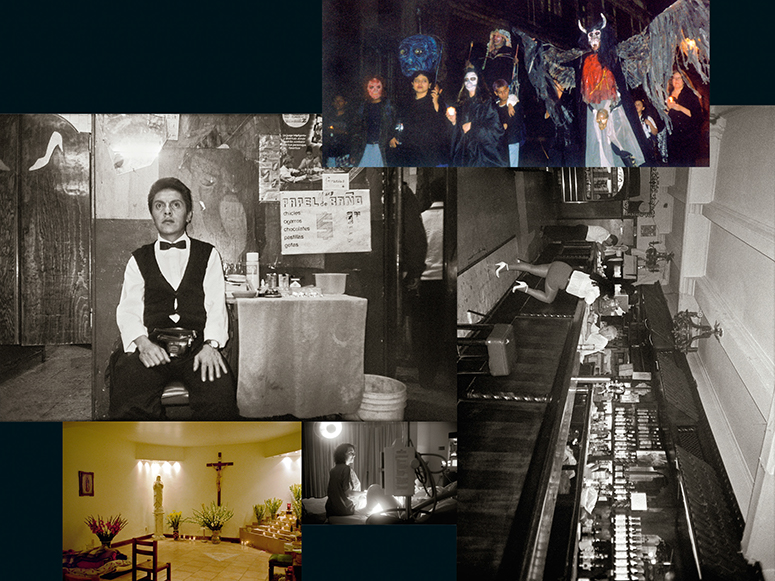

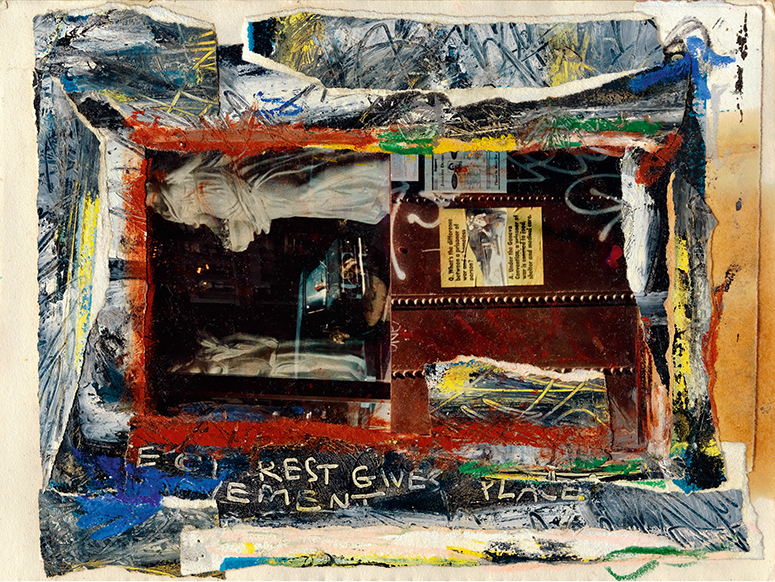

But the photographs do more than just illustrate the story line. It demonstrates Kip’s way of looking at the world. The ordinary people that he notices, the man-altered landscapes that pass him by on his journeys, the random details that trigger his interest. It shows an almost innocent curiosity with the world around him, a world that can be in vibrant colors or in restrained black-and-white, a world that can be pin sharp or artfully blurred depending on the circumstances. A world punctuated by notes and scribbles and found photographs. A world filled with observations that drown out his feelings. The pictures exude a quietude, a passive wonderment with everything that is happening. Or perhaps with everything that is not happening.

At the same time Brookman turns the persistent notion of photographs as bearers of truth on its head. When Kip and Addie find themselves in a diner on the outskirts of LA being served by a woman called Judy, the reader-viewer immediately associates the photograph of a waitress name-tagged Judy with the one mentioned in the text. Even if the story is fictional, she must have been real, right? Even though the photographs may reflect Kip’s personality perfectly, they are not his. The imagery for Redlands is derived from Brookman’s own photographic diaries, as well as from his sketchbooks, his collages, and his archive material. In fact, the images existed long before the words did, and Brookman used them as building blocks to construct this wonderful edifice. Unsurprisingly, he takes great pains to point out at the end of the book that: “All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental”. It serves as another nod to cinema. The reader-viewer almost expects the final credits to roll up: “The End.”

Philip Brookman

Karin Bareman is a writer on photography and audiovisual culture, and also works as assistant curator at Foam. She obtained an MA in Visual Anthropology from the University of Manchester, and lives and works in Amsterdam.

(All rights reserved. Text @ Karin Bareman. Images @ Philip Brookman.)