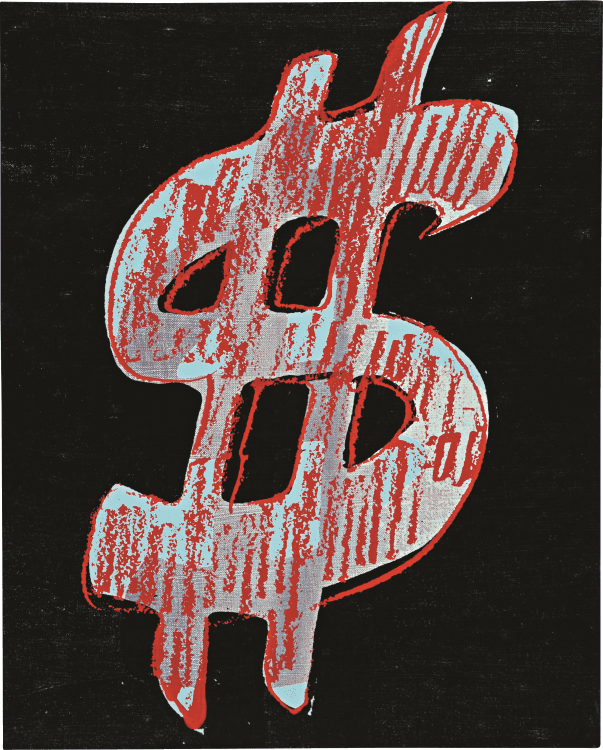

Dollar Sign, circa 1981

“Am I really doing anything new?”

By Kenneth Goldsmith, Wayne Kostenbaum and Reva Wolf, excerpt from I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews

From an interview with David Bourdon, 1962-63

WARHOL: Am I really doing anything new?

BOURDON: You are doing something new in making exclusive use of second-hand images. In transliterating newspaper or magazine ads to canvas, and in employing silks screens of photographs, you have consistently used preconceived images.

W: I thought you were about to say I was stealing from somebody and I was about to terminate the interview.

B: Of course you have found a new use for the preconceived image. Different artists could use the same preconceived images in many different ways.

W: I just like to see things used and re-used. It appeals to my American sense of thrift.

B: A few years ago, Meyer Schapiro wrote that paintings and sculptures are the last handmade, personal objects within our culture. Everything else is being mass-produced. He said the object of art, more than ever, was the occasion of spontaneity or intense feeling. It seems to me that your objective is entirely the opposite. There is very little that is either personal or spontaneous in your work, hardly anything in fact that testifies to your being present at the creation of your paintings. You appear to be a one-man Rubens-workshop, turning out single-handedly the work of a dozen apprentices.

W: But why should I be original? Why can’t I be non-original?

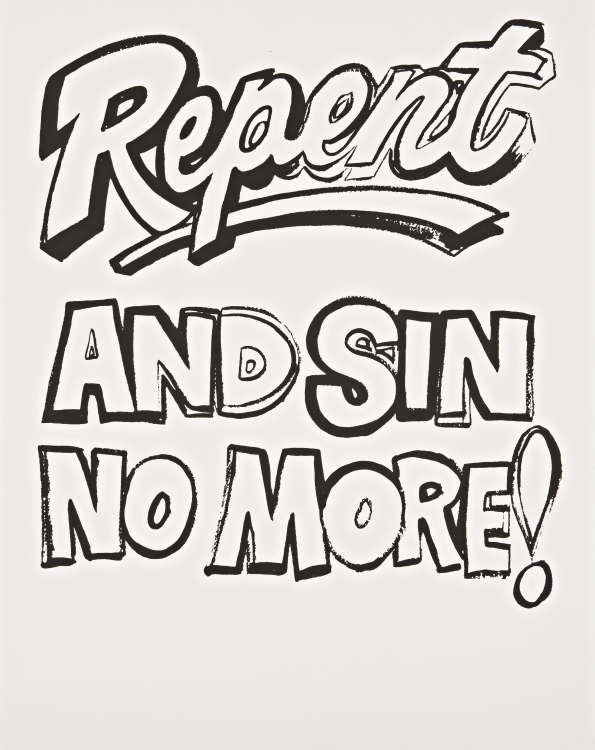

Repent and Sin No More! (Positive), 1985-86

“But why should I be original? Why can’t I be non-original?”

B: It was often said of your early work that you were utilizing the techniques and vision of commercial art, that you were a copyist of ads. This did seem to be true of your paintings of Cambell’s Soup and Coca-Cola. Your paintings did not depict the objects themselves, but the illustrations of them. You were still exercising the techniques of art in your selection of subject, in your layout, and in your rendering. This was especially true of your big black Coke painting, and in your Fox-Trot floor-painting, both about six feet in height, where the enormous scale did not leave enough room for the entire image. In Coca-Cola the trademark ran off the right side of the canvas, and in Fox-Trot, step number seven occurred off the canvas.

In these works, you were taking what you wanted stylistically from commercial art, elaborating and commenting on a technique and vision that was second-hand to begin with. I believe you are a Social Realist in reverse, because you are satirizing the methods of commercial art as well as the American Scene.

W: You sound like that man on the Times who considers my paintings to be sociological commentary. I just happen to like ordinary things. When I paint them, I don’t try to make them extraordinary. I just try to paint them ordinary-ordinary. Sociological critics are waste makers.

B: But for all your copying, the paintings come out differently than the model, because you have changed the shape, size and color.

W: But I haven’t tried to change a thing! You must mean my unfinished paint-by-number paintings. (The only reason I didn’t finish them is that they bored me; I knew how they were going to come out.) Whoever buys them can fill in the rest themselves. I’ve copied the numbers exactly.

“I’m anti-smudge. It’s too human. I’m for mechanical art.”

B: You don’t mean to say that otherwise you have copied the picture exactly. It’s so identifiable as your work. The flower stems in your still-life have an awkward grace that is typical of your work.

W: I haven’t changed a thing. It’s an exact copy.

B: (Then your hand has slipped.) It’s impossible to make an exact copy of any painting, even one of your own. The copyist can’t help but contribute a new element, or a new emphasis, either manual and psychological.

W: That’s why I’ve had to resort to silk screens, stencils and other kinds of automatic reproduction. And still the human element creeps in! A smudge here, a bad silk screening there, an unintended crop because I’ve run out of canvas – and suddenly someone is accusing me of arty lay-out! I’m anti-smudge. It’s too human. I’m for mechanical art. When I took up silk screening, it was to more fully exploit the preconceived image through the commercial techniques of multiple reproduction.

B: How does it differ from print-making – serigraphs, lithographs and so on?

W: Oh, does it? I just think of them as printed paintings. I don’t see any relationship to printmaking but I suppose, when I finish a series, I ought to slash the screen to prevent possible forgeries. I somebody faked my art, I couldn’t identify it.

B: I have always been impressed by your multiple-image paintings, especially your paintings of movie stars, like Marilyn and Elvis.

W: So many people seem to prefer my silver-screenings of movie stars to the rest of my work. It must be the subject matter that attracts them, because my death and violence paintings are just as good.

Continue Reading Here:

I’ll Be Your Mirror: The Selected Andy Warhol Interviews

ASX CHANNEL: ANDY WARHOL

(All rights reserved. Text @ David Bourdon, Kenneth Goldsmith, Images @ the Andy Warhol Foundation)