Compulsion #1, 2012 © Alex Prager, courtesy M+B Gallery

She admits not to have chosen her full name Alexandra as ‘there are a lot of people who are more comfortable working with a man’.

By Elena Dolcini, originally published at tyci.org.uk, reproduced with permission on ASX

Alex Prager is an American artist born, living and working in Los Angeles.

She admits not to have chosen her full name Alexandra as ‘there are a lot of people who are more comfortable working with a man’. This obviously sounds as an ambiguous and controversial statement, but yet the truth is not far away.

However, as a female she fully understands and empathises with selfhood-related dramas she stages in her photography. Her actresses are charming women often disquietingly frightened by an event that happens out of the viewer’s sight, or main protagonists of melodramatic scenes led by misfortune, horror and death, all shoot with a retromania attitude.

Born (1979) and living in Los Angeles, Prager couldn’t help but referring to movies and their stars, both from the past and more contemporary times.

If Alfred Hitchock is a ubiquitous presence in her practice, in terms of the peculiar women’s repertoire and birds that unfailingly fly over photographs’ skies, David Lynch is another mentor for Prager’s work. The way she deals with crowds, for example, reminds of Lynch’s eccentric humankind, where eyes wide open, still postures and faces’ expressions in distress disconcert the spectator.

The American photographer dwells in between fashion and fine art, blurring the two territories not without an ironic attitude, and creating a new space where she can experiment with short films.

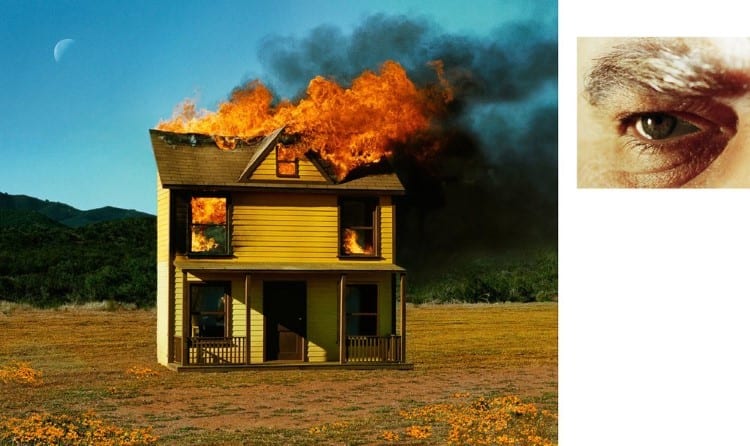

4.01 pm, Sun Valley and Eye #3 (House Fire) 2012, © Alex Prager, courtesy M+B Gallery

When asked about her influences, she cities both artists related to the fashion industry, such as Guy Bourdin, and unique personalities who contributed to a new perception of photography, such as William Eggleston.

If there is something Prager shares with the latter is doubtlessly a meticulous attention to cars as objects and the status symbol they represent in the American society of consumption; she portrays candy-coloured cars, regretting old times where they still haven’t been depersonalized by a lifeless grey.

This is Prager’s world: a retromaniac obsession for the past, dressed up women with plenty of make up on their faces and vintage clothes, which might not mean to be ostensibly chic, but end up to be exactly voguish. After all, she is also a fashion photographer and she does it splendidly.

The French critic Roland Barthes indicated three strategies used by fashion to communicate its message: literal representation, when an object is mimetically represented on the catalogue, romanticized view, when life becomes acting, and mockery, when the scene is rather absurd and surreal. Prager synthesizes the last two by endorsing a staged photography where women live melodramas as in a Lichtenstein comic painting: she, in fact, shares with the American painter the same preference for red polished nails and voluminous hair, and, alike the pop artist, treats this idea of womanhood with irony and art licence.

Prager confesses most of her work is done during post-production, suggesting that an image is just an object meant to be modified by human tastes and aims

Prager’s shoots epitomize what fashion was for French art critique; the realm of desire where images become erotic due to a constant focus on women (in this case) and their paraphernalia. Far from being just ornaments, their clothes hypnotically capture the viewer’s attention and constitute a place where imagination can proliferate. That’s the difference between the high status of erotic literature, which is, as for Prager, not related to sex, and pornography: the latter parades everything with a flat, tiring and monotonous language, the former rather implicitly suggests details which nourish curiosity for appealing and intense images.

To borrow words form Roland Barthes again: ‘It is intermittence, as psychoanalysis has so rightly stated, which is erotic: the intermittence of skin flashing between two articles of clothing (trousers and sweater), between two edges (the open-necked shirt, the glove and the sleeve); it is this flash itself which seduces, or rather: the staging of an appearance-as-disappearance’.

Prager’s works are often characterized by the presence of water; in the short film ‘La Petite Mort’, the protagonist ducks into a pond and then re-emerges on the surface, and in the photograph ‘Pacific Ocean’ (from the series ‘Compulsion’) people float dead or, when alive, scream in terror.

Here water can symbolize a different state of being: things are observed from another prospective if blurred in murky seas and happen as in a ‘parallel dimension’. The girl from ‘La Petit Mort’ seems to experience ecstatic moments of inner calm, easily interpreted as a pre-birth (or post-mortem) status and therefore implying another female symbolism; perhaps not by chance the French word, la mer, which means sea, is feminine and only a ‘e’ separates it from mother (la mere). But psychoanalysis brings up too many concerns to face them here.

Prager confesses most of her work is done during post-production, suggesting that an image is just an object meant to be modified by human tastes and aims; photography doesn’t necessarily mirror reality and the current high technology constantly pushes this medium towards new boundaries.

After all, Lichtenstein once said that art is about perception, not nature.

[nggallery id=537]

ASX CHANNEL: ALEX PRAGER

(All rights reserved. Text @ Elena Dolcini, Images @ Alex Prager)