Vergara shows exactly what has happened to these neighborhoods. By essentially dumping the new shelters and apartment buildings in devastated, minority neighborhoods on the outskirts of Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, Harlem and the Lower East Side, the city was able to avoid many lawsuits from powerful community groups.

By Frederique Krupa, November 21, 1991

The New American Ghetto, on view (1991) at the Urban Center and Storefront for Art and Architecture, illustrates the problems of current urban community planning. The show is centered around the photographic research of Camilo Jose Vergara on a more general level and a detailed study of Mott Haven, The Bronx by advanced students at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. (At the Urban Center, a ten-minute narrated slide show runs continually and serves as an introduction to the ideas presented in depth at Storefront.)

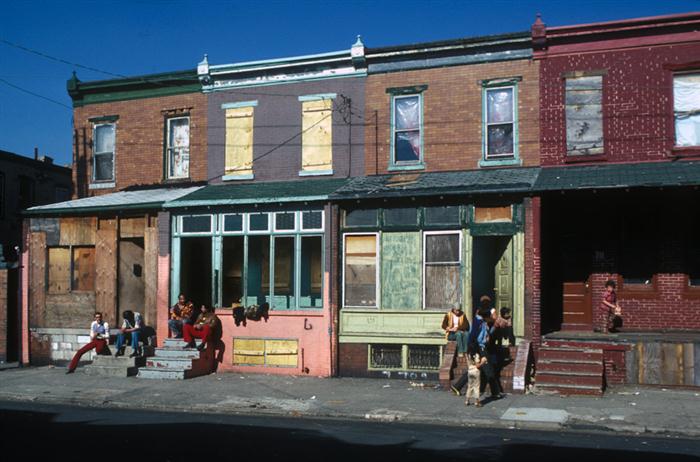

The exhibition at Storefront wraps around the gallery walls with color-xeroxed images applied like wall paper. A horizontal band of computer graphics at eye level traces the students’s analysis of Mott Haven; above and below are Vergara’s series covering the wall from floor to ceiling. The stated aim of the show is to bring about a radical change in current planning; however, it also demonstrates the futility of architecture, no matter how well planned, in solving the problems – on its own – of poor, drug ridden neighborhoods.

Camilo Jose Vergara, a sociologist/photojournalist, has spent the last twelve years photographing the developments of new American ghettos, tracing the deterioration of buildings, and amassing 8,000 slides, half of which are about New York Ghettos. Using the information he collects, he narrows in on the complex aspects which have lead to the deterioration of these buildings, usually involving the drug trade, and the solutions which attempt to remedy the situation.

In this show, Vergara focuses on the ten-year plan begun by the Koch Administration. Due to the media’s sympathy to the homeless and the corruption scandals that emerged in 1986, Koch decided to provide the city with 84,000 new and 168,000 renovated apartment units. Thirteen large shelters for the homeless were added, bringing the total cost of this project around $5.1 billion. The city was thriving at the time and could borrow the money, even though the Reagan Administration was reducing federal support for such programs. The press accepted the plan enthusiastically and uncritically for the most part and played a big part in selling it to the public. This plan was going to resurrect blighted neighborhoods.

Vergara shows exactly what has happened to these neighborhoods. By essentially dumping the new shelters and apartment buildings in devastated, minority neighborhoods on the outskirts of Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens, Harlem and the Lower East Side, the city was able to avoid many lawsuits from powerful community groups. Due to the severe economic crisis of the early 70s, the city already owned many buildings and lots in these areas due to the wave of abandonment by landlords who could no longer afford to pay their taxes. Most importantly, these neighborhoods already had a large transient population who lacked the time or the resources to get organized. The city chose to put these NIMBYs (Not In My BackYard!) where there would be the least resistance and lawsuits from community boards.

The neighborhoods chosen also happen to be drug trafficking centers where violent crime is rampant, and effective programs dealing with these problems are rare. Vergara illustrates that placing the most susceptible members of society in shelters and buildings in these areas is feeding the problem; few people are benefiting from this plan, aside from the dealers and perhaps the builders. He shows us what drugs do to a building, and what residents have to do to keep drugs out of their building, often hiring guards and/or risking their lives. If these measures fail, the building is sure to deteriorate. Using a photographic series of buildings in the South Bronx taken over a decade, Vergara traces the developments that drugs inflict on buildings: a dealer gets an apartment; the front door remains broken; an addict sleeps in the hallways; robberies occur; a fire breaks out in the apartment that has been serving as a crack den; people with the means to, move out; the empty apartments are pillaged for pipes and appliances often leaving running water which floods other apartments. This occurs until the remaining families have no choice but to go to a shelter, and the building is condemned and usually razed.

The neighborhoods chosen also happen to be drug trafficking centers where violent crime is rampant, and effective programs dealing with these problems are rare.

The study of Mott Haven by the graduate students is equally informative. In the form of computer graphics, they analyses the different factors which together make Mott Haven the most advanced of these new ghettos. The South Bronx is going to get 44 percent of the permanent housing for the homeless, as well as seven large shelters, making it in the words of Vergara, a “special zone for the homeless industry.” In 3D maps, the students set about linking the shelters to crack, heroin, shootings, prostitution and Moses’s highways. The first set of graphics ties together the known crack and heroin houses (purple and yellow cubes) to the location of the 149 shooting (generic symbols of people, extruded for thickness, with red splotches on their chests) that have occurred in a nine month period. The 36 fatal shootings are illustrated with the people symbols knocked down. The brilliant use of computer graphics is at first disturbing, but it soon becomes a vehicle to step back and look at the situation more abstractly and more rationally. The graphics then tie in the new shelters, one of which is for homeless women, many of whom have drug problems. Prostitution gets tied into the map and leads to Robert Moses’s highways.

Moses contributed many positive elements to New York. He got 1/7th of the total WPA money set aside for New York; he constructed parks, swimming pools and many other major public works. However, he was an egomaniac. In the 1950s, he stubbornly refused to reroute a mile of the Cross Bronx Expressway, a route just a feasible, which could have prevented the loss of 1530 apartments in the center of the solid, ethnically-diversified community of East Tremont, 30 blocks north of Mott Haven. The ugly but ineffectual battle that ensued with the residents would later serve to discredit Moses. In the end, the highway was built according to Moses’s wishes and slowly destroyed East Tremont’s working class community. Moses, who did not drive, created these highways for the families who could afford cars, to be able to travel faster, to get to his wonderful beaches and parks.

The absolute practicality of Moses’s visionary highways makes Mott Haven easily accessible from just about anywhere in the tri-state area in under twenty minutes. This makes Mott Haven a strategic location for drug trafficking, linking the truck drivers, prostitutes and dealers in a neat menage-a-trois. The truck drivers spread the news and soon people come from as far as Connecticut and New Jersey, rarely needing to leave their cars to obtain their drugs.

This exhibition, intended as a response to the press’s uncritical acceptance of the plan, is successful for demonstrating that a radical change is necessary. It achieves this agenda by being clear, concise, thorough and not condescending to the viewer or to the subject matter. Vergara wants these ghettos to be dismantled and never reproduced, an admirable goal. He has shown that irregardless of how much money is invested in these neighborhoods, nothing is going to change unless money is spent on reeducation and support programs, detox and police to name a few. Recently, the courts have decided on a Fair Share rule to combat the concentration, stating that NIMBYs must be spread out over all the neighborhoods. This comes too late to really change anything in the ghettos, but it is a start. The Dinkins Administration wisely refused to release a list of shelter locations around the city, in fear of lawsuits from the powerful community boards. It would be amazing to see a shelter on Sutton Place.

The New American Ghetto is really timely since it raises many more questions that must now be resolved. How should we be approaching this problems? How are we going to get people to accept their share of NIMBYs? What should the focus be on, services or construction? What do we do with the existing ghettos? Are ghettos inevitable in our capitalist society? In conclusion, the exhibition serves to illustrate that architecture alone will not solve these huge, complex problems and that the time has come to seriously examine the solutions.

http://invinciblecities.camden.rutgers.edu/intro.html

http://www.translucency.com/frede/ghetto.html

ASX CHANNEL: Camilo Jose Vergara

(© Frederique Krupa, 1991. All rights reserved. All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher)