“I had been blessed with an innate, a built-in, quality of design composition–of composition, not just design composition.”

Interview with Julius Shulman

Conducted by Taina Rikala De Noreiga at the Artist’s home in Hollywood Hills (Los Angeles), California. January 12 & 20, February 3, 1990.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Let’s start by you telling us when and where you were born.

JULIUS SHULMAN: I was born in Brooklyn, New York, 10/10/10 [meaning October 10, 1910–Ed.], as were two sisters and one brother. And my mother and father had come from Russia, separately, at the latter part of the last century. The family moved to Connecticut when I was a few months old.

My father was a farmer in Central Village, which is northeast of Norwich, which is in turn about twenty miles up the Thames River from New London, Connecticut. That’s on the way up towards the Rhode Island/Massachusetts border. We had a large farm, I don’t remember how large, one hundred acres or so. Apparently we lived off the farm, which was a mile and a half outside of Central Village. My two sisters, brother, and I walked to school every day. I was then five years old (1915).

What I remember in my deepest memory is strange, because here I was sitting next to my mother on an open wagon. She drove the horse. My father with other members of the family, the brothers and sisters, on another wagon in front of us, leading the way. We apparently had been riding the horses and wagons from our previous farms, where we had lived for a short time. I remember my father waving to my mother towards what appeared to be a house up on a slight rise in the land above the roadway–dirt road of course. He turned with his horse and wagon up the drive to the farmhouse where we were to live the next three or four years. That was the beginning of my memory of our approach to the farm and the ensuing experiences.

Recall: My mother and father worked the farm with one helper. We lived off of it. There was an occasional buggy trip to Moosup for fresh meats, chicken, and fish–a distance of three miles.

Of course, as children, we failed to realize how gigantic a task was performed by our mother. I have a profound respect for her. As with the women of the covered wagon days, walking mostly across deserts and prairies, snow-covered mountain passes, and constantly in fear of Indian attacks were daily events.

At least my mother was capable of raising five children. The youngest was born at home shortly after we arrived in Central Village. Up at dawn to care for the scores of chickens, collect eggs, milk the cows, and then to prepare breakfast for a family of seven! Yet there was the ability to bake breads. Between those chores she cut potato “eyes” to prepare the planting with my father, whose horse-drawn plow furrowed the soil.

Of course we had one of those deep, dark, cold, cement cellars, which people had in the Midwest and on the East Coast. No one had refrigeration. We didn’t have ice boxes, for sure. So everything was in the cellar–my mother used to make preserves, put up vegetables and store items that had to be kept cool.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Did they make money with any of their products?

JULIUS SHULMAN: No. I don’t think they sold their farm production, eggs perhaps, because my mother had a large number of chickens. Rhode Island Reds, I remember the name. The chickens attracted foxes. Our farm was in a forest. I remember hearing noises in the morning, at dawn, and my mother and father would dash out with sticks or brooms because a fox would be trying to get into the chicken coop. Many wild animals inhabited the forests. Deer, fox, raccoons, possum are some I recall. I remember one day my father chasing a deer trying to catch it for me, but it jumped over a fence, away it went.

Life was fascinating because farm life continued on until I was ten years old. I would wander away from the house. My mother would come looking for me, and I’d be found by a little pond on the side of the forest, at the edge of the farm. My mother first would look through the corn fields. My mother enjoyed relating to the family how she found me, quite frequently, talking to a snake. I never forgot those moments.

But anyhow, that was the beginning of my association with Nature–on that farm and continuing with California, 1922, Boy Scouts, hiking, camping, relation with photography, it’s effect on composition and pictorialism. [After moving to Central Valley, California in 1920–Ed.], within a couple of years I joined the Boy Scouts, and I continued, apparently, my association with nature. And this has never left me, and this has had a lot to with my avoidance of commercial work.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Under what circumstances did your father decide to move, do you know?

JULIUS SHULMAN: I don’t know, except this: In those days, California was magic. It was the land of gold, and you heard stories from people. My father apparently knew people who had heard about–from their friends or relatives–about California. It was a land of opportunity. It was a land of endless possibilities, physically, climate, and economically–which of course turned out to be true, because we came here in September of 1920 by train–mother, father, five children. And you think of the covered wagon days, this was deluxe because you traveled by train, stopped in New York for a couple days–my mother and father had brothers and sisters there–then we took the train and went on to California. Traveling with five children cross-country I guess is no picnic even by train. My brothers and sisters and I went to the elementary school here, at Alpine Street School, near Sunset Boulevard and Figueroa Street. My father’s store was on Temple Street a few blocks away.

It was difficult for me to understand how my father did accumulate enough wherewithal to make the drastic moves in the family’s life. He did have one other occupation when we lived in Central Village. He was gone for a long time certain parts of the year, and it turns out that he had connections with fur trappers in northern New England and into the Canadian New Brunswick province. He would purchase fur pelts–I remember in our barn loft on the farm there were many fur pelts hanging. Apparently furriers came to the farm from New York and purchased the pelts, which must have provided a substantial income! The farm provided essential food stuff. Central Valley’s population of 293(!) hardly was a market, except my mother did sell eggs, corn, potatoes…

I remember a cellar filled with jars and crocks of preserved vegetables and fruits, and my mother put them up; she was able to cook or store them. I still see my mother baking bread and making rolls on a big table where she able to roll out the dough. It was like magic. And our stove was a six-burner wood and coal stove. And I remember lying under the stove playing with our cat–I was five or six at the time–my mother cooking and working. The water supply came from a pump on the sink, a hand pump. The toilets were outside. Sears Roebuck catalogs for paper.

Now in retrospect all those events on the farm are so strange and remote, but they’re all part of a lifetime. We had a crank telephone. The number I remember was one-eight, ring five. Then came our first view of an automobile. One day we heard a noise on our driveway. One of the neighbors, a farmer, had just bought a Model-T Ford. We had never seen an automobile before! That was about 1916 or ’17, about the time of World War I. I remember one time an airplane flew over the farm, and the phone began to ring. All the farmers around were asking, “Did you see the airplane?” What an event for a farmboy in 1917!

We had no electricity, of course. We had kerosene lamps, and, “My God,” you would ask, “how did you get along in this world?” But we did.

The baths were in the tubs in the middle of the kitchen, hot water boiled on the stove, and my mother did all this. She died at the age of 87, out here, a few years ago. My father had died young. He just burned himself up. But my mother raised the family.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: So what did your mother do here in Los Angeles?

JULIUS SHULMAN: Well, she ran the store. My father had a drygoods store, first on Temple Street, then they moved to Boyle Heights, in 1922. And they established a very successful business. My brothers and sisters worked there after school. They didn’t go beyond high school… I was the only one of the five who went to a university. But the brothers and sisters all worked in the store with my mother. My father died in 1923, so my mother ran the store, with the family.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: So your mother was left with some very young children.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yes. Didn’t seem to faze her because she managed the kids, everything. By 1923, when my father died, my older sister must have been 17. The next sister was a couple years younger. My older brother then was near 14 and in 1923 I was 13. So they were old enough to work in the store, so all four, even my younger brother, the four–two brothers and two sisters–worked in the store with my mother. They didn’t pursue other interests. It was a family kind of store, and they had a tremendous business going there. Boyle Heights had a widely varied population, mostly Jewish. But there were Spanish, Japanese, Gypsies, Russians, blacks.

I wrote a dissertation about life in the Brooklyn Avenue environment and the herring barrels, the open stores. It gives an insight into the kind of life we had and also is in response to an article that Art Seidenbaum, who used to write a column for the Times… [Now deceased.–JULIUS SHULMAN] Art had written an essay about the need for a new town to take care of Los Angeles’s burgeoning population, and I in response said “No, that isn’t necessarily the answer, because we have integration of ethnic groups on Brooklyn Avenue. I wrote about how on Brooklyn Avenue you would see gypsies with their multi-layered skirts with large families with numerous children coming into the stores. There were also Japanese, Mexicans, Germans, Russians. Many “white” Russians (refugees from the revolution of 1917) lived down in the East First Street area near the L.A. River west of Boyle Avenue.

I used to work in the store on weekends and holidays to help the folks, because they needed a lot of help in those days. And this is how it all began economically. We lived two blocks away up in a nice old 1906 redwood house that my folks had purchased.

Our mother and father always purchased their own homes, and that’s a family trait. Even to this day, we all have our own homes. My mother used to admonish us: “Never, never give up the opportunity to buy or build a house. And pay for it as quickly as possible.” I paid our mortgage in seven years on my own house, which was built in the 1949-50 period. Because I never forgot. My mother always used to say, “Be in your own business.” Also as with her feelings about home ownership, she always used to admonish us, “Never, never go into a business partnership with anyone.”

She never had any formal education. When she came here from Russia, she must have been 13 or 14 years old. My father was not much older. But they met in Brooklyn and got married there and raised a family. And that was it. They had a candy store at the beginning in Brooklyn for a short time. Then they moved to Connecticut. Apparently they didn’t have much joy or friendship with the rest of their families, so they gave that up and got away.

We always had our own homes, and my mother, besides taking care of the store, with my brothers and sisters, who really managed it very well, but she would always go home and do the cooking. And the store was open till late at night. It wasn’t one of those 9 to 5 businesses. It was a neighborhood store; you don’t close at five o’clock. You stay open till eleven o’clock at night.

And the brothers and sisters were very compatible, and they shared the hours and the work, and my mother would be home cooking, preparing meals, and the brothers and sisters would come home–I was going to UCLA by this time–a couple at a time, have a meal, go back to the store. And my mother would do the dishes, clean the house, do the laundry whenever, wax the glistening hardwood floors on her hands and knees, and then come back to the store, and go to work.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Maybe people had more energy in those days.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Not energy, no, not so much energy as–and this can be attributed to how people live and work today–they were ambitious, strong, capable, and they didn’t watch the clock. They watched the store.

And that was the secret of the family’s success! By 1928 I graduated high school, and I decided to go on the university. I entered UCLA in September 1929, the first class on the Westwood campus.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: What high school did you attend?

JULIUS SHULMAN: Roosevelt High School, and that’s in Boyle Heights. I graduated there in June 1928. I went to UCLA in September of ’29. I didn’t enter UCLA in September ’28 because I waited a year. I remember purchasing my first car. It was a 1923 Model-T Ford. Cost me thirty-eight dollars. I remember it so vividly. And during that year I was already active in the Boy Scouts, camping and hiking. I spent considerable time in the activity, aside from weekends helping the folks in the store, becoming indoctrinated in outdoor living.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Can you recall an interest, an early interest in photography, or…

JULIUS SHULMAN: No. What happened in my photography experience began briefly in 1927, when I was in the eleventh grade in high school. We had a choice of a course in art appreciation for a semester or, then, what was one of the first photography classes in the United States. In high school, we were given the opportunity to have a course in photography.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s interesting, I’ll say.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Very unusual. So I enrolled in that class. The family in those days had an Eastman Box Camera.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Right.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Everyone had Kodak box cameras. It wasn’t called a Kodak; it was just called “Eastman Box Camera.”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: I see.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And so for the class we had assignments to take pictures around… We were near Hollenbeck Park, which is a few blocks away from Roosevelt High School. We used to go there for assignments and take pictures of the lake area and a beautiful old wooden bridge. I did well with the box camera, and found that I was able to take care of the assignments and got very good training in how to develop roll film in the darkroom and make prints. Then one of the assignments, which was very important, to photograph events at the southern California high school final track meet at the Coliseum. This was in May 1927, and the assignment from the teacher was to take a picture of a track meet action. He warned us, “You can’t photograph action with your Brownie box cameras. If any of you have a chance to get or borrow a news type of camera, which has higher speeds to stop the action of sports, try to get that, because you can’t do much with a Brownie.” So anyhow, I went to the track meet, and found I was able to get a location where the high hurdle races were being set up, up and above the tunnel where the track meet still is run from today. The hurdle races start from under the tunnel and run out over the hurdles towards the east end of the coliseum. And I set the camera there, after observing the attendants setting up the hurdles for the race. I said to myself, “Gee, that looks good in the viewer of the camera.” When the race started I took a picture as the hurdlers came over the first hurdle. Now I found that negative here in my files…

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Oh, that’s exciting.

JULIUS SHULMAN: …and I made an eight by ten print of it; 1927, and it’s a beautiful photograph!

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s great.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Had a good eight by ten glossy made in the school lab, and I got an A in the course! The photography teacher was astounded. Of course when you take a picture in action with the action going away from you or towards you, it’s not as blurred as when it’s going across your field.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Right.

JULIUS SHULMAN: So it turned out that I had a very successful picture of the hurdlers as they came over the first hurdle below my vantage position.

Angeles Magazine did an essay on my life and experiences in the March 1990 issue. Having on file the original 1927 negative, I gave them a new glossy, which was published with more current work. I never ever dreamed of being a photographer. Matter of fact, I didn’t get a Vest Pocket Kodak camera, with which I started my serious photography, until 1933 or ’32–five years, six years later–and that was just by accident. Somebody gave me the camera–for a birthday or something. I didn’t have anything to do with photography, after 1927 or ’28 when I went to the university. Or when I went hiking and camping I didn’t think of taking pictures in those days–until 1932 or ’33 when I began to take pictures with my Vest Pocket camera. I still have many of those pictures. Some were printed in the above issue on the Angeles Magazine.

Then ’34 to ’36 I was up in Berkeley for two years. ‘Cause a friend of mine was getting his master’s degree and he knew I was bumming around at UCLA after two weeks in their engineering class where I was enrolled. You see, I was a ham radio operator in the twenties, from 1926. I was interested in electrical-technical things, so I thought, well, at UCLA I’d enroll in electrical engineering, which was the closest thing… Of course at that time electronics hadn’t been “discovered.”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Right.

JULIUS SHULMAN: No one knew anything about the technique of refined electronic work of any kind. We had electrical engineers, period! And some semblance of interest in radio. So after two weeks at UCLA in the engineering school, I dropped out. Then the ensuing years I wandered around UCLA, auditing courses. I wasn’t enrolled for a major because I didn’t know what I wanted to be.

So after those years, my friend said, “Look, you’re not doing anything. Why don’t you come up to Berkeley with me and get an apartment. You can live off the land as easily there as you do here.” It turned out that I did go to Berkeley and started taking pictures of buildings around the campus.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Now that’s interesting.

JULIUS SHULMAN: I still have a file of those. I have all my negatives. And I used to take portraits of students they’d send home to their folks. And I would frame the pictures of the campus buildings and sell them at the bookstores, and department stores in Oakland, Berkeley.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: So was it an interest in architecture, or what?

JULIUS SHULMAN: No, I hadn’t even met an architect–not until 1936 when I met Neutra.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: They were just nice buildings.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yeah, the old-time buildings on the campus.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And here I was roaming around taking snapshots of the buildings. The Campanile at Berkeley I shot from the [Hearst–Ed.] Mining Building arched windows, and the Daily Bruin newspaper published it full page one time. They made a remark in the editorial that here’s a photograph taken by one of our students that no one had ever in the history of the campus had ever taken of the Campanile before, framing the picture–I’ve got it here in the stack somewheres–framing the picture with the Mining Building curved window.

It was also published in the Angeles story. The point is that this started me in photography in a strange way. I had taken landscapes and scenic pictures–on camping and hiking trips which ensued–but architecture was an unknown subject. My Berkeley campus buildings photographs were curiously coincidental to my accidental meeting with Neutra in March 1936.

At the end of February 1936, I thought, “I’ve had enough; I’ll go back home.” The family missed me, and I missed the family. I decided to return to L.A. I had had enough as an academic drifter!

A couple weeks after I came home, my oldest sister, who had a drugstore near where the Richard Neutras live, on Silver Lake Boulevard, introduced me to a new draftsman, who had come from Washington, D.C., and was working for Neutra. Mrs. Neutra had asked my sister, “Did you have an extra room or something where this fellow could live?” So my sister did have this space in her house, near the Neutras. She introduced me to this young man one time, feeling that we would have a lot of common interests. I had never met an architect before in my life. He said to me one Sunday, one day, “I’m gonna visit one of the new houses that Mr. Neutra’s finishing… Turns out to be right down here on Fairfax and Hollywood Boulevard, just a couple of miles from where we are now. The Neutra Kun House.

And I met him, or drove with him, to the house, and while he was inside inspecting, whatever–I didn’t know what that meant–but he was inspecting the finishing part of the house–it was just being completed–and I took snapshots with my Vest Pocket Kodak camera–five or six pictures. I made eight by ten prints that week and gave them to my friend. On Saturday, March 5, I got a call from him. He said, “Mr. Neutra has seen the pictures. He liked them. He’d like to purchase them from you,” and said that he would like to meet me. So I drove to Silver Lake, met Mr. Neutra, and he asked me who and what I was. Of course I was nothing ’cause I hadn’t any ideas of being a photographer.

He was, as I say, the first architect I’d ever met. And those pictures, by the way, of the Kun House, are still being published and were published. They were used in Neutra’s books, and I still get calls from publications for that house. The same Vest Pocket Kodak pictures, I still have the negatives on file.

And at that time Raphael Soriano, who was just beginning his work–and this was in March 1936–was doing his first house, the Lipetz House, up on the hill above Silver Lake’s south end, as Neutras pointed out. Neutra said, pointing up at the hill above the lake, at the south end of the lake, “Why don’t you drive up there and meet Soriano, who is there every day supervising the construction of the house?” I drove up that afternoon, met Soriano for the first time. We became good friends. And strange, we started our respective careers that same year. And I did pictures of the house when it was completed.

Also Neutra gave me other assignments to photograph in the ensuing months. Neutra introduced me to other architects who were active in the post-depression years–Gregory Ain, Rudolf Schindler, J. R. Davidson, Harwell Harris. The early pioneers were all beginning, and here I was with my Vest Pocket Kodak.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: How interesting.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Strange.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: So what was that first architect’s name, who introduced you to Neutra?

JULIUS SHULMAN: This is a young draftsman, I never remembered his name. I wish I did. I may have some reference somewheres. Somehow it slipped my mind. I may have it in reference somewheres.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Do you recall what your impressions of Neutra were at that time?

JULIUS SHULMAN: None whatsoever.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: No?

JULIUS SHULMAN: He was just a person. And architecture didn’t mean anything to me. And yet the strange thing is that–and this was apparently exposed in my first pictures on the campus, at Berkeley–they were good pictures. I was able to identify with composition. And my compositions of my landscape pictures, prior to going to Berkeley, my early landscapes… I have one which was shown on an NBC program. They had a series of programs interviewing photographers not too long ago. And in that period of time, I brought down a group of my photographs to the studio, NBC, and we laid them all out on a large table, and I was interviewed, and the commentator… What’s his name? He was the man in charge, the host on the Groucho Marx show. I always forget his name, but it’s not important now. But he picked up a picture from the group lying there, and it was a landscape I had done in 1933 or ’34 in Berkeley of a windswept tree up on the hills, up in the hills of the little town of Lafayette, which is on the back side of Berkeley. And he pointed to that landscape, that tree picture, and said, “Photographers don’t like to show their old work because they feel they can always do better in later years. Now here’s a photograph…” He turned it over, and it said 1933, Lafayette, California, and so on. He asked me how I felt about this picture. “If you went back there today, could you do it better, since this was taken apparently with your Vest Pocket Kodak?” And I exclaimed, loudly I remember, I said, “Oh, no! This is a magnificent photograph!”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [laughs]

JULIUS SHULMAN: “This is a perfect photograph! And if I went back with an eight by ten camera, or a four by five view camera, I could never have done it as well as I did then.” “It’s not the camera,” I remember exclaiming, “it’s the composition.” And I pointed out how the windswept tree, as it was leaning over, the tip of the tree, the most remote area of the tree, was hanging down close to the ground, but it seemed to be pointing to a curved row of trees in an orchard, way in the distance, and it made a perfect “S” curve in the composition. And I said, “There’s nothing you could change about this picture.” And I remember my wife afterwards… She was sitting in the control room, and the operators there were, they were watching this on the monitor screens, and when I exclaimed to the commentator about how perfect this picture was, they said to my wife, the operators, they said, “My God, your husband’s very modest, isn’t he?” [laughter] But they admitted it was a good picture.

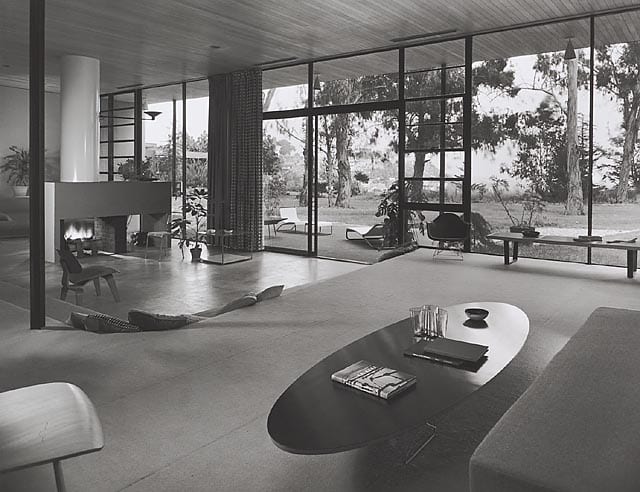

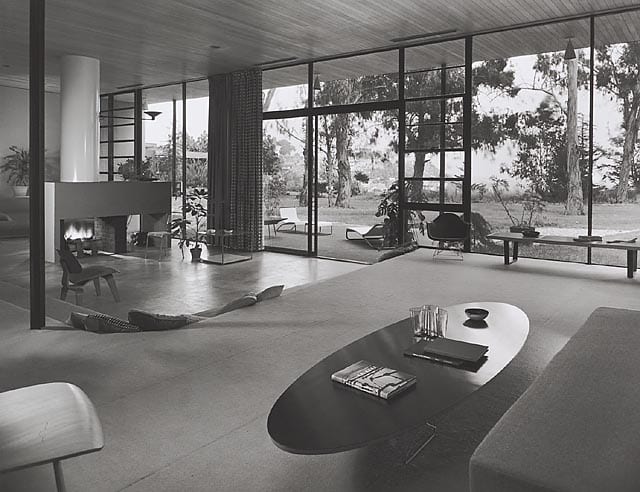

Well anyhow, the point is it shows that I must have had a built-in facility for composition. It shows in all my landscape pictures, all my personal pictures, everything I took. And when I got into architecture, I was able to define design statements. And as I look at any of my old photographs, they possess some quality which I pursued in a natural way in my architectural photography. And I’m very proud of some of those photographs, because no matter where you see any of my works, and I demonstrate this to my students all the time, that the secret of photography is composition. Assembling–identifying to begin with–and then assembling these statements, these thoughts, in your mind without the camera. Matter of fact, I don’t allow cameras to be used in some of my seminars, at least for the first day or half-day discussion. I say, “Let’s learn how to take pictures without a camera. And let’s learn to identify–whatever we’re photographing, whether it’s a landscape or a building or an interior–let’s look first and see how we identify ourselves with the object.” Then when we take out the camera, we’ve assembled these design thoughts in our mind and we’ve put together the composition, showing all four sides, all four edges of the camera view, possessing the elements of what we want to photograph.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: You speak as if you implicitly understood design in architecture though, so my curiosity is, was it in just hanging around with Neutra and Soriano, people like that? How did you pick up…

JULIUS SHULMAN: No, I didn’t hang around with these men!

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Well, but they sent you out to do some photographs.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Well, that’s just it. Because here I had never met an architect before, yet when I look at my 1936 pictures of the Neutra Kun House, they are no different than anything I would do today. If I went back to the house, down the hill here, with my four by five camera–or whatever camera–and took new pictures, I couldn’t have got better compositions.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s really _____.

JULIUS SHULMAN: So in other words, I had been blessed with an innate, a built-in, quality of design composition–of composition, not just design composition. So when I went out to photograph… Like the earliest pictures I did… The Soriano Lipetz House was completed not much longer after I met Soriano, and I remember the first pictures, which we still use. They were good. They’re very adequate, and they really told the story of Soriano’s work.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: I guess what I’m getting at is this idea of your ability also to make sense of design. You bring it back to…

JULIUS SHULMAN: It’s a mystery.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah. You bring it back to composition, but others of us who have viewed your photographs wonder about your sensibility about design. Because your photographs often are very telling. They are quite descriptive about the design itself.

JULIUS SHULMAN: I don’t know.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: You don’t know.

JULIUS SHULMAN: It’s puzzling to me. It’s been on my mind forever.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [laughs]

JULIUS SHULMAN: After working for 54 years–’36–this is my 54th year in architecture, and all my pictures–wherever I go, whether new or old pictures–they’re good. And I say it publicly and very explicitly.

A picture of a hotel in Hawaii. What prompted me to drive across the bay–that’s the Kona Surf Hotel [Big Island, Hawaii–Ed.]–and I had looked from the hotel across the bay, from the hotel, and I saw this tree, and the water, and I thought, “Hey! Let’s go across there and look at the hotel from the other side of the bay.” And here’s a magazine, a trade magazine, Hotel-Motel News, and the editorial comment about my pictures. And the editor wrote, “This month’s cover photograph of the Kona Surf Hotel was selected to illustrate a point we feel too many hotel owners have ignored in developing their property.” He said, “No amount of advertising could secure the kind of exposure generated by the top-quality photograph printed, provided by the Kona Surf and Intra-Island Resorts Company. This is the point we’d like to make. If a hotel–this is a hotel magazine, so they’re stressing hotels–or resort owner developer is willing to spend the relatively small amount of money to obtain top-quality photographs of his property, those photographs will return to his investment several times over in increased publicity and exposure to his property.” Then he goes to say, “The Kona Surf people commissioned renowned architectural photographer Julius Shulman of Los Angeles and flew him to the islands for a five-day shooting trip. The fruits of their efforts are seen on the cover and at the top of this page. Rather than stark mediocre photography, they received art, which not only shows what the property looks like, but captures a mood which can be easily promoted and appeals to magazine and newspaper editors as a high-quality illustration.”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s nice.

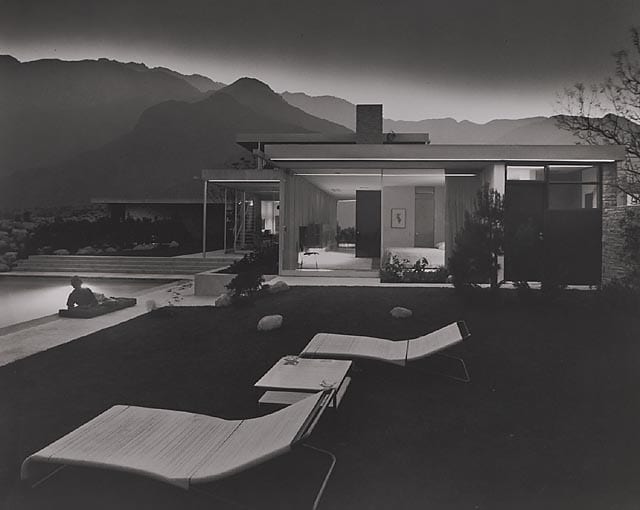

JULIUS SHULMAN: But anyhow, he goes on and on, talks more about my photography. The point I’m making is I did this many times, like in this 1947 photograph of the Neutra Kaufman House in Palm Springs, which is standing here. It’s a twilight picture, which is a 45-minute exposure. I had been doing photographs with Neutra at the house, and towards evening, as the sun was setting, I noticed, looking out to the eastern desert, there was a beautiful glow in the sky, and I said to Mr. Neutra, “Just a moment. I want to go outside and look at the house from the eastern side of the property.” I looked at the house and I thought, “My God! Look at the twilight developing, and look at the mountains, and the scene which was being created by the changing light!” So I quickly ran into the house, against the will of Neutra, because Neutra was insistent that we continue working, because he wanted to do more interiors in the house. So I said, “No, Richard, we can’t do that. That sky is beautiful, the mountains are beautiful, and the light glowing inside, the exposure values are just right.” So I ran out with my camera and my film bag, and I set up the camera, and out of this came this photograph. And I had a shutter which didn’t have to be cocked. You can open and close this shutter at will, expose two or three seconds at a time, and then run into the house and turn on lights, turn off lights, and built, kept, like building blocks, kept building my exposure for this scene. And out of this came this photograph. Now the point I’m making is I didn’t know what I was doing.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [laughs]

JULIUS SHULMAN: All I knew was it was a beautiful thing, and I was going to try to capture the elements of this design and the mood of the mountains, the twilight, the magic. It turns out this is one of the two most widely published architectural photographs in the world.

[Tape 1, side B]

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Let’s go back, if we might, to the pre-World War II years, once again. In looking at this book, The Photography of Architecture and Design, I read one of the bits that you wrote that says that “Those days”–pre-World War II–“possessed the great secret–time–of which we seemed to have plenty–or at least enough for a little longer to look at ourselves and our work.” You go on to talk of some of the architects. I’m interested in this notion–you’ve brought it up already once–about the sense of time in life and how that was different, and I’m wondering if some of your consciousness then of taking photographs and the competence you gain also has to do with the fact that the pace of work and the time was different. Perhaps you can tell me a little bit about that. Do you feel that there was a possibility of a greater self-consciousness in one’s work at that time because there wasn’t a rush? Or people didn’t expect things to happen yesterday?

JULIUS SHULMAN: Well, now, let’s go back to 1927, ’28, in high school. Roosevelt High School had a four-story building. I imagine it still has. Our physics class was on the fourth floor and my seat was by a window looking north towards the San Gabriel Mountains. And in those days they hadn’t discovered smog and I used to do a lot of hiking, as I mentioned before, and from the window I could identify all the mountains I had been to the top of.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And they were beautiful, the “purple mountains majesty,” from a song by the same name. [The words “purple mountain majesties” also are found in “America, the Beautiful,” words by Katherine Lee Bates, melody by Samuel A. Ward–Ed.]. You could feel that. Now I remember Douglas Caby. He was a physics teacher. He would occasionally call over to me and say, “Julius, if you could tear yourself away from looking at the mountains”–because he knew of my hiking all that–“I’d like to have you

SHULMAN, JULIUS

answer the question that I just asked the class.” [laughs] Of course I didn’t hear the question; I was busy daydreaming. This was inherent in my personality from day one. I was always meditating, if you will. I was always thinking of other things, quietly, peacefully. The beauty of nature. I was looking at the mountains. I could identify all… I’ve been hiking all my life, and I think I’ve hiked to the top of every mountain in the San Gabriel range.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Oh my, that’s great.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Including the San Bernardino Mountains. There’s not a mountain peak that I don’t know. And I used to hike alone most of the time because there weren’t many people who were interested as much as I was. I would roll up a blanket pack and throw some canned beans in a rucksack–we didn’t have rucksacks–old army knapsacks in those days.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Right.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And I would take off and take the Red Car (the Pacific Electric) from Brooklyn Avenue from Boyle Heights and the Red Car went to Sierra Madre, and then I’d hike up Mount Wilson trail and then from there hike to the back country.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: I was just on that Wilson trail last Sunday.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Oh, all right.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Seven or eight miles of it. [laughs]

JULIUS SHULMAN: All right, so that’s my life.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s wonderful.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And then, the point I’m making from there on in… I was married in 1937, the year after I did that Neutra essay [_____________–Ed.], and in those days I had my Kodak camera. I didn’t get the view camera until ’37 or ’38, the bigger camera. But in those days we had a group of friends with whom we used to go camping and hiking a lot, and every holiday… We’d called ourselves, loosely knit organization, The Mountaineers [no relation to the present-day organization–JULIUS SHULMAN], and we would go to Death Valley, or Yosemite, or Sequoia, or wherever the group of us would decide, and would go camping for a long holiday weekend. Three, four, maybe four and a half days, or whatever. And most of the people were professionals. They could get away. I worked at my darkroom at home–such work as I had. My income was anywheres from one to two hundred dollars a month. Our rent was twenty-five dollars a month for a four-room flat. Didn’t cost anything to live. And if we had a chance to go on a trip next weekend with our friends, my wife and I thought nothing of taking off. We had an Oldsmobile–let’s see, 1939, we had a 1939 Oldsmobile sedan. Before that I had a 1932 DeSoto coupe. And we used to take off and go hiking and camping. Drive the car to Mt. Whitney, for example, and go to Whitney Portal and hike up to the top of Mt. Whitney, or something.

I remember in 1939, in September, we were camping out at Whitney Portal, and I just walked over to the car, turned on the radio, just by chance. I heard the news that Hitler had invaded Poland, September of ’39. The beginning of World War II for us.

So we had time. No inclination to hurry. What few assignments I had–one or two a week maybe–I brought the negatives home, processed them, made the prints, and dried them and delivered them, and went on to another assignment. But I have my record book here, which I found recently, my book from 1940 or 1939, I think. One year, about that time of the book, I made a hundred and _____-five dollars in that month. Which was a lot of money. [Tape noise obscured some of the words beginning about here–Trans.]

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: A lot of money.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yeah. So anyhow, the point is that I never was in a hurry. Money was not of the essence of existence, and apparently having the time not to hurry, not having other things to go to, to do, no other commitments… I remember photographing a house with Gregory Ain one time. Brand new house. Who had landscape architects in those days? Who had money to provide any trees or any shrubs? So Gregory would always say, “Let’s go put some geranium shoots, cuttings, into the ground, especially those with blossoms.” These were all black and white photography, of course, in those days. So we would cut branches and stick them in the ground, and make them look like trees or shrubs. But we had all day! And we’d take ten or twelve pictures in the day–with my view camera or my Vest Pocket camera, whichever I was using at the time–and that’s it. You weren’t thinking about how much it would cost. I didn’t charge a per-photograph fee to the architects. Ten or twelve dollars, fifteen dollars, for the days’ work. Money was nothing. Life was simple.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: A different sense of time, and a different sense of money.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yeah, that’s right. So I remember, for example, living a half block away from a Safeway market on Pickford Street near Washington and La Brea, and my wife would say to me, “Julius, why don’t you go to the store and get a few things I need.” So I would take fifty cents. Silver half dollar. I wish we had ’em now. [laughter] And I’d go to the store and get a quart of milk for a dime, half a dozen eggs for a dime, a loaf of bread for a dime, and a quarter pound of butter. Forty cents, and I’d get ten cents change.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah, my God.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And there’s enough material to provide the basis for a good lunch. Forty cents. [laughs] We had lunch the other day at the Santa Barbara Biltmore. We went Sunday for brunch and never dreamed what they charged. We got the check. Brunch for two of us cost seventy-seven dollars!

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Oh, my goodness.

JULIUS SHULMAN: For brunch for two people! We’ll never go back there again.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s extraordinary. Much too much.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Way out of line. An abundance of food and whatever. Obscene! All that waste of food. Five or six serving stations, different people working there, where you got your entrees. Plus you helped yourself with the other things. It was kind of overabundant. It left us with a very bad taste.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Never realized what a waste there! Well anyhow, that’s another reason for understanding values, because the people working there serving probably received the minimum wage. Four dollars, maybe four and a half dollars an hour–if that much.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And I thought, as we were taking–they have huge mounds of shrimp, beautiful large shrimp–and while we were helping ourselves to this shrimp, a fellow came out with a container, a large bowl, of new shrimp to replenish the supply, Hispanic fellow. You can just see he was a minimum-salary kind of guy, and he was dumping those shrimp out onto the tray where we were getting the serving, and I remarked to my wife, I said, “Olga, look at this poor guy dumping this shrimp out, and we’re paying”–at that time I didn’t know, but it turned out we were paying an exorbitant amount of money–“how much of that money that we’re paying went to him? Nothing.”

So in other words, this is the way life goes. This man has to count his pennies. We didn’t in our early years, because we got forty cents worth of staples at Safeway. And twenty-five dollars a month rent for a four-room flat. So it didn’t take much to live, and a hundred and seventy-five dollars or whatever I made a month at that time was a lot of money.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: You could still put money in the bank even. [chuckles]

JULIUS SHULMAN: We did, we did. Matter of fact, one year… I got in the army October 1943.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: I was going to ask you about that.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And prior to that month, I was busy. Business was very good.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Business was good here in L.A.?

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yes! In photography and architecture. And that month I was photographing for Arts and Architecture magazine the synthetic rubber plants on the south end of L.A., where they manufactured all the ingredients which produced synthetic rubber for the war effort. And I was taking photographs for the building contractors, who were building these projects. The Shell Company was making the butadiene, which was one of the components of synthetic rubber. The Dow Chemical Company had another plant adjacent, where they manufactured the chemicals that went into the production, and then Goodyear or U.S. Royal, U.S. Rubber Company, which produced and combined the synthetics which went into manufacture of tires. So I had these three clients, and that last month, in September of 1943, I made three hundred and thirty dollars!

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Wow!

JULIUS SHULMAN: It’s a fortune. Not saying of course I included the cost of the processing and making the prints in that three hundred thirty, in the cost of the assignment. But the point is I didn’t know any better. The customary thing was to charge extra for prints. I didn’t do that. If I give the architect a bill for ten dollars, I gave them the prints without any additional charges. Who charged mileage or expenses? I worked out of home, it’s me, it was just nothing. Of course in those days photography expenses were very minor.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah.

JULIUS SHULMAN: But life was easy. And then when I went into the army, of course, I spent two years in an army hospital doing medical photography, surgical photography.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Oh!

JULIUS SHULMAN: And it was another world. And then all the time that I was gone, the Museum of Modern Art in New York was building up its archives of contemporary architecture. And my archives at that time were consisting of the early work of Neutra and Schindler and the early architects I mentioned before. And as a result, since my wife was home, and she had the negatives–we had a good file system–she kept sending the negatives to a friend who had a darkroom and a full finishing place, and he made the glossy prints. And she would mail the pictures to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and we’ve gotten an income from those photographs. And while I was in the army, she lived at her mother’s house, and so we had no expenses, so we made money even while I was in the army. Because as a private the first part of my army career, I was getting… What was the army pay for a private? Thirty-two dollars a month, I think.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Pretty slim.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And then I became a sergeant after that. And I think my salary was maybe forty dollars a month, so on. So whatever money I made I sent home. So we made money out of our photography career even in those years. [chuckles]

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s quite extraordinary.

JULIUS SHULMAN: But you see, the main thing is life was easy. I was always quietly composed in my pursuit, always lived at home, worked at home–as I do now. Nothing is changed. I’m not in a hurry. Never have been. I’ve never pushed. I drive the same way when I’m on a highway or a street. I’m the slowest car on the road. Like when we went to Santa Barbara last Sunday. Took the back road by way of Highway 118, Simi Freeway, to Fillmore, Santa Paula, two-lane, the old-fashioned roads from way back, even though I’m driving a Volvo which is a high-speed powerful car. I was cruising along, the slowest car on the road on the Simi Freeway. I was going sixty miles an hour. Cars were passing me up as if I was standing still.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Oh yes.

JULIUS SHULMAN: But I was enjoying the road, the drive.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah, plus it’s a…

JULIUS SHULMAN: And it’s a beautiful feeling, to be composed in your own life , in your own mind. To be able to set your own pace.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yes.

JULIUS SHULMAN: No one’s ever pushed me. Deadlines. Never had deadlines.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Well, that’s good.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yes. So anyhow that’s my life. And that is what helped me in my work, too, so much, because I was not in a hurry. I remember one of the major assignments I did after the post-war years. I was photographing the Bullock’s Pasadena store that Wurdeman and Welton Becket had designed. Their biggest project too, because prior to that time they had been doing residential projects–Pennsylvania Dutch houses in Beverly Hills. And then suddenly they got this huge commission to do the Bullock’s Pasadena, and I was given the assignment to photograph that when it was complete. I remember going there on Sundays–for the exteriors especially–stopping the car, taking out my four-by-five camera… I recount this experience to photographers and students even today. How do you start photographing a building? Where do you establish your point of interest? The focal point of the composition of the design of a building–whether it’s a home or a department-store complex? And I remember getting out of the car and looking at the building. I didn’t walk around with the camera. Some people do even today, but I never did that. I just simply looked around, found compositions which put together the elements–as I said at the beginning of this conversation–and out of it came my photographs. And then we went back to do interior photographs on Sundays. I had an assistant work with me on the interiors. We brought in our lights, and we spent all Sundays. The store was empty, all by ourselves. The maintenance people, the security people opened things up for us, turned on power and lights whenever we needed it. No hurry. We did a hundred and fifty photographs of that store, because they had a public relations firm handling their work, and they sent photographs to every trade magazine in the country: women’s wear, men’s wear, household utility equipment. Every trade magazine that published things on stores. And then the architectural magazines as well made extensive coverage of the Bullock’s. Of course it was a unique store. Post-war department stores were few and far between in those days. And this was one of the best, one of the few ever done in those early years. But the pictures turned out to be very successful and Wurdeman and Becket became very well known throughout the country and, of course, the firm became one of the most largest, prominent architectural firms in the world in the succeeding years. And, as they mentioned in this hotel magazine, good photography helps, you see.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yes, definitely.

JULIUS SHULMAN: So there’s a statement that comes out from this work. I don’t think that photographers today–and architects–are as conscious of photography values as I was in the early years. And the architects too learned in the early years, especially when their work became published. I got requests from magazines. This magazine I just showed you, Baumeister, from Munich, Germany, that company, who, incidentally, used my photographs in the 1940s. And this girl who called me, she wasn’t even born in 1940.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [laughs]

JULIUS SHULMAN: When I told her on the phone, “Oh, I remember your firm. We did photographs for the Calway Publishing Company, that published the Baumeister–architectural building master is what the name means–she said, “1940 or ’41, my God, I wasn’t even born.” Which was a strange thing.

But the point I’m making is that my photography from day one was consistent with identifying the elements of architecture. I wasn’t thinking, as I did in succeeding years, of the art forms or the art elements of photography, as I mentioned in my book. I said the responsibility of the photographer is to identify the design components of a structure, to identify with the architect the purpose of the structure, of his design. Then in the course of providing and producing these design statements, if you could come out with an art-like statement, for the purpose of intriguing and enticing the art directors of a magazine, so they get the pictures on a cover perhaps, then you have produced a double-barreled, a double-bladed, a double-edged sword to attack the promotion process of architectural publicity. And this is what I try to state in the book about the purpose of architectural photography. And the picture on the cover, for example, the picture of the Lever House in New York, by Skidmore Owings Merrill, I took that photograph on my own when I was in New York. I was traveling around the country photographing an essay for a story on architectural environmental design influence, and when I set up my camera to photograph the Lever House, I noticed the Seagram Building, which was across the street, and I went across the street and framed the Lever House with the structural columns of the Seagram Building. I had received a request about that time from Arquitectur d’, an architectural magazine in France, in Paris. They were doing a story on American architecture. They happened to ask me if I happened to have a picture of the Lever House. And of course I had that in color as well as black and white. I sent that picture that’s on the cover of that particular issue of the American architectural story they did, and then somebody brought in the magazine to the Skidmore Owings and Merrill offices in New York, and waved the magazine in front of the PR, public relations, people and the architects working on the floor there, and they were overwhelmed. The PR woman called me on the phone, and she said, “Mr. Shulman, when did you take that photograph? We have never seen such a picture of Lever House ever before, and no one ever photographed it in respect to its role in the siting of the building, in relationship to the Seagram Building across the street.” After all, the Seagram is a very famous building too, by Mies van der Rohe and Phillip Johnson. So here is a picture which depicted a building in relationship to its neighbors, which developed a statement of design and environment. Now why did I do that? Not how, but why? To this day, it’s still a mystery.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [chuckles]

JULIUS SHULMAN: I’ve always been able to associate environment–the site–with my architecture.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: And that’s very significant. It comes out in the story that you were telling about the Kaufman House.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yeah, exactly.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: And in that story you also talk about you’re gaining technical expertise, because you said you were going back and forth trying to work on the lighting and _____ this long time exposure.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Ah, yeah, that’s right. But on that Neutra picture, I took one negative. By that time it was dark, and by that time Neutra was pulling me away. He said, “Come on, let’s go, Shulman, let’s go. We’ve gotta finish the interiors.” We hadn’t had supper yet. Neutra never paid attention to eating.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [chuckles] Really? So his sense of time was a little different from yours.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yeah, yeah. He was urgent. And Mrs. Neutra used to tell me all the time, “Richard hasn’t got time to eat.” He died young, in his sixties or early seventies maybe. Of course he was pushing, driving, driving.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That photograph in particular is a very beautiful photograph artistically. A few minutes ago, you said you weren’t perhaps aware of creating an

art-type photograph, yet in your struggle to do something technically _____ _____ produce something that was beautiful and artistic.

JULIUS SHULMAN: I did see the mountains.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: You did see the mountains or something like this.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Of course I had been to the top of Mt. San Jacinto several times in those years, and I knew the beauty of the mountains from the top down. But to see the mountain range at twilight with the interlocking, interweaving, of the ranges, one on another, that’s what caused me to want to photograph this house under those circumstances. So it all came together: my background of nature involved. And the respect for nature. And all this comes together. Neutra did a book called Mystery and Realities of the Site, and much of this editing material he used in the book came from our photographs, where I identify his buildings with the site, and all of a sudden he’d say, “Hey, that’s a good subject for a book.” Published a rather nice little booklet.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: So it was actually your sensitivity to his work and the site that was…

JULIUS SHULMAN: Which was infused, that’s right.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Well, or gave him the idea.

JULIUS SHULMAN: It was infused into his concern and his identification of his own architecture.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Exactly. So you showed him a way of seeing it, perhaps in a way he hadn’t seen it before.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yes, that’s what probably happened. Now this Neutra picture is perhaps one of the few ever shown of this house.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yes.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Very few of the Neutra house–the Kaufman House–pictures were ever shown, other than this photograph.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah, and that one is a lasting image.

JULIUS SHULMAN: That’s right.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: It’s recognizable and…

JULIUS SHULMAN: And it told the story. This is what architecture is all about. This photograph has appeared in every architectural magazine in the world ever published since ’47, and it’s appeared in every book on architecture. I don’t think any book that we have around here fails to show this picture.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Oh, that’s extraordinary.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Everybody publishes it. And it points the need–which is lacking today, I think, and I try to impress architects to learn a little bit about photography so they can impress their new young photographers to understand the need, the significance of careful design, of compositions. And I’ve learned a lot too from architects. I remember from Neutra. He was always insisting that we photograph his buildings before they were complete, before they were landscaped. But he was always bringing loads of branches, mostly eucalyptus. It’s a joke today among many of the older architects who’ve been around for year who used to be apprentices for Neutra. I’d see them at conventions or meetings or seminars, and they’d say, “Hey, Julius, I remember we used to hold branches for you.”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [chuckles]

JULIUS SHULMAN: [Edward–Ed.] Killingsworth and Peter Kamnitzer and some of the early architects. Ray Kappe. All of these people worked for Neutra one time or another in their careers, and Neutra would come with a carload of branches and strew them on the ground, have one of his people hold some branches overhead. And one of the pictures I remember I have Mrs. Neutra’s wrist and hand holding a branch on the edge of the negative. [laughter] Without the branches the houses would be naked!

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah.

JULIUS SHULMAN: But I learned about the values. We did an assignment in later years for Good Housekeeping magazine, one of Cliff May’s low-cost $12,000 tract houses, out El Monte, Covina, somewheres. Good Housekeeping had arranged with Cliff May for us to take pictures of this particular house. It was supposed to have been ready. We got out there that morning. There wasn’t a stick of landscaping. Not a shrub.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Hmm.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And it was the deadline, in this case. Somebody in the house told us, “There’s a nursery down the road here.” So I went to the nursery and rented some canned plants–five gallon cans of roses and geraniums, whatever they had in bloom–and set them up in front of the house and framed the picture with these plants, and we broke off a branch from a walnut tree that was growing nearby and fastened the branches to a lightstand so we could frame the picture with an arching branch to look like there was a tree there. And in the finished pictures, the house is perfectly landscaped.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [laughs] That’s a good story.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Then in the patio we’d move the same “trees” and branches and plants and cans in front of the camera. We cut more branches, and made it look like the house was landscaped.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: With the consistency of landscaping, the same…

JULIUS SHULMAN: The same material–right!–the same plant. Now when I produced the pictures… I was going to New York about that time. I remember bringing them to Mary Kraft. Mary was the architectural interior editor of Good Housekeeping, and she thought the pictures were lovely, as she said, and after the story came out–at least I was wise enough to restrain myself–after the story came out, she sent me a copy of the magazine, and she said, “We’re very proud of what you did for us.” I wrote back–I shouldn’t have–I wrote back to Mary Kraft, I said, “Dear Mary. Thank you very much for the nice presentation you made of the Cliff May house. I thought I’d let you know for future reference, for photographers and architects, that if they come to a house and there’s a deadline, there’s no landscaping, this is what we did.” And I sent her a picture. My assistant took a photograph of me with my camera. It’s in my book. Yeah, it’s in the book. A picture of me with the landscaping, with the cans, the plants, showing how we framed the picture. She wrote back, angry, in her letter, “Julius, how could you! If I had known that you falsified the landscaping, we would never have published the house.”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Huh! What a surprise.

JULIUS SHULMAN: She was so pleased with the pictures, but she felt annoyed. And many of the editors then (maybe now are that way, too), but in New York, architectural editors were real square about accuracy. They wanted to identify the landscaping. For example, they wanted to identify the name of every shrub, the species of azaleas. They wanted to know everything.

We had a similar experience with House and Garden magazine in the period of time I’m describing. We went to photograph an azalea garden of a house, a very well known landscape architect, out in Pasadena. And I went and worked with Ellen Sheridan. She was one of the editors of House and Garden on the local scene at that time. We had bad weather, during the springtime when we have foggy days for weeks at a time, and we couldn’t get any sunlight. So finally when we did get out there the azaleas had died back. No more blossoms. What did we do? It turns out the species of azalea they had were mostly, or almost all white. Like we have white ones out there behind you now in garden. See the white azaleas coming out? Now, those azaleas in our pictures were created. The blossoms were created by little tufts of Kleenex. And Ellen Sheridan and I walked around the garden tearing off Kleenex and putting them carefully onto the prow of the branches, the leaves, and we restored the white “azalea” blossoms throughout the garden.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [laughing] That’s amazing.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And when House and Garden published that picture, they talked about the white azalea blossoms. And when you publish this picture into a half-page or whatever, you can’t see whether they’re Kleenex or azalea blossoms.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Right.

JULIUS SHULMAN: But we never told them.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: You wised up on that one.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Yeah, I never told them.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s funny that they didn’t understand.

JULIUS SHULMAN: So this is another thing about working in photography: You never take anything for granted. Your creative juices are flowing, and you’re saying, “Hey, let’s do something about this.” I could have gone to the phone.

That’s what Mary Kraft said to me, “You could have called me on the phone and told me the circumstances, and I could have maybe given you a couple more days.” In my response to her, by return mail, I said, “Well, Mary, I respected your deadline and I always meet your deadlines, and I wasn’t about to ask for a postponement.” And also I think I said that the house was open to the public about that time, and we couldn’t stop the people from coming through, and interfere with all my lighting equipment on the interiors. This way the house wasn’t quite open for the public yet, so I had it to myself, and I explained that in my letter, but she grumbled nonetheless. But I remember seeing her again in New York the next trip I was there, and I, she still remembered, and she still scolded me.

Yet the reader interest is great, because that house was a prototype that Cliff May had designed and they sold. They built 30,000 of those houses in different parts of the United States.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Mmmm!

JULIUS SHULMAN: It was a best seller. Of course, it was a terrific value. Cliff May was a great designer. And that house was a tremendous success–not only because he instilled in the house the quality of his design philosophy, but he also had a great respect for low-cost housing nonetheless, even though his forte was always his expensive, big palatial California ranch-type houses, for which he’s still known to this day. And this house was a tremendous success. And much of it could be attributed to the story that Good Housekeeping magazine did. And Cliff May wrote her a letter of great appreciation. That still didn’t simmer her down when she saw me. [laughter] She still just wagged her finger, waved her finger at me: “You shouldn’t have done it!”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s wonderful.

JULIUS SHULMAN: She grumbled over a martini for lunch. [both chuckle]

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s really funny. That’s a good story.

JULIUS SHULMAN: It is fascinating. We did this many times. Like with Richard Neutra when he did the Channel Heights wartime housing in San Pedro, for the wartime housing, shipyard workers. The houses too were not finished, but Neutra had furnished one of the interiors with his furniture–his chairs and things. And we wanted to photograph the house for Architectural Forum, and he brought branches, and one of the scenes, looking from the living room through the kitchen to the outdoors, showed a naked landscaping and houses on this cross-street under construction. He said, “Let me go hold a branch in front of the kitchen window.”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [laughs]

JULIUS SHULMAN: Take time out.

[Interruption in taping]

JULIUS SHULMAN: Now to continue about Neutra and the Channel Heights project, Neutra said, “I’ll go outside and I’ll hold a branch in front of the window to hide the houses across the street.”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s funny.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Which he did. Now I had set the camera and a signal arrangement I had with Neutra–since the windows were closed he couldn’t hear me–he would stand there. When I waved my hand, when I pulled the slide out of the film holder and cocked the shutter, ready to go for a one-half second exposure, whatever it was, then he would sit down and hold the branch and I would click the picture. So here is the famous architect, Richard Neutra, sitting on the ground, holding a branch in front of the window.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [laughs] If only you could have had a photograph of that.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Just then a couple workers walked by–and everyone knew him because the project had been going on for months, and he was there every day. Everyone knew the famous architect Neutra. And I could see the men looking and pointing to Neutra from across the street and laughing. “Now why in the goddamn world’s this guy sitting on his rear? The crazy architect is sitting on the ground in front of this house holding a branch.”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s quite a wonderful thing.

JULIUS SHULMAN: And what could he say?

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: He couldn’t move if he had to.

JULIUS SHULMAN: He couldn’t point to me: “He’s having a picture tooken.” [laughter] So anyhow I delight in that little story, because it points out the importance of caring. Now in the finished picture, which has been used extensively in the Channel Heights publication, you see the branch. You don’t see the unfinished buildings across the street.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s _____.

JULIUS SHULMAN: It’s a fascinating thing that, to what extent he would go to produce a picture. But he was one of the few–very few–architects who knew the value, as they mention in this hotel magazine I showed you before, about the value of good photography. It’s not the cost. Because every architect I’ve ever worked for has become world-famous, because of the publicity they get. And the magazine people in New York used to tell me this all the time. I went to New York several times a year because I worked on a personal basis with every magazine. I mean every magazine that published anything about architecture interiors and exteriors. Shelter magazines as well as technical magazines. And book publishers, too. And the editors used to tell me, “Whenever a package of pictures came from you, we would all stop what we were doing and gather around the conference table and lay out the pictures.”

We had an experience… For example, I was photographing in those early years, in the fifties and sixties especially, a lot of work in the Midwest–Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri, and so on. For a long time I did a lot of work in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for Crites and McConnell’s architectural firm, who I knew when I was giving lectures at Iowa State University, when they were still students. And when they became architects, I began to do their work. One year I went to Cedar Rapids and photographed seven projects for Ray Crites throughout the state of Iowa. I was going to go to New York from Cedar Rapids, so I had the film processed and contact prints made by a photographer’s store who had processing lab who we could trust. He processed the pictures, and I took the contact prints to New York with me, to the Architectural Forum magazine, and met with MaryJane Lightbown, associate editor, and Doug Haskell, who was the editor. Joe Hazen was the executive director. Paul Grotz was the graphic designer and art director. We all went to lunch, and on returning to the conference room, we laid out all the pictures around the perimeter of the table. Joe Hazen came in with the group, saying, “Now, let’s see what you got from the land of the tall corn.” They were joking about cornfields in Iowa. “What else was there?” And it turns out they were so impressed with these buildings they published all seven in the Architectural Forum in the ensuing month or two.

And then after that Life magazine was doing a story–since Time and Life [Incorporated–Ed.] was publishing these magazines at the time–on the young architects and designers and professionals who were forty years old or younger who were bound to be on the road to success, and they chose Ray Crites as representative of the young architects in this country.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: That’s nice.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Mainly because they saw his works so successfully published in the Architectural Forum magazine. All based on good photography–and good architecture naturally. But good expression. You can’t define architecture without good photography. And nowadays, of course, tragically the buildings are being shown in the architectural magazines in beautiful, beautiful color, full-page blowups, and the buildings are hideous and the color is beautiful, so they publish these pictures, and that’s supposed to represent architecture.

But it’s only, I feel, a veneer. It doesn’t really show the true nature… Oh, of course, I can’t put them down entirely. Some of these buildings are striking and very relevant in terms of present-day architecture. But it’s not the truth, though. It’s not what architecture truly depicts in our society. And we have the responsibility then of producing, doing what we can with the best we can find in the existing buildings.

But I refused–and I mentioned this publicly–to photograph the post-modern architecture–of homes especially, commercial buildings, too. I just stopped working with architects. See, that was one reason why …I retired three years ago. And now I devote my time to doing my archival work and to responding to requests from all around the world. We have three more books coming out this year besides the new one that came out on steps and stairways. These are pictures which we helped assemble from all over the world, many of them my own photographs, which I had on file, pictures showing steps and stairways in all their infinite numbers of designs, shapes, and forms. And all this is coming back full circle now, with the development of an understanding of the fact that architecture wasn’t so bad in the fifties and sixties–that we’ve literally discarded and discounted what was being done. Now we’re coming back to realizing that this was a good period (the forties through the sixties, and continuing into the seventies)–perhaps the best period we ever had in our architectural development.

[Tape 2, side A]

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Tape number two, Julius Shulman, and I’m Taina Rikala.

I wanted to ask you next about John Entenza and Esther McCoy. When did you first meet Entenza? What was the occasion? You’ve shown me an early issue of Arts and Architecture magazine, so I realize you were familiar with the magazine. But tell us a little bit about that association.

JULIUS SHULMAN: The outcome of my early work–actually the origin, I suppose, too–occurred when the architects with whom I was working–there weren’t many of course–in the thirties and into the forties, particularly in the early forties, late thirties… The architecture that was being produced in those days was shocking to most people. The public had never seen architecture as we knew it, the so-called International Style, the all-steel and glass–and hardly even steel in the early years, just a frame plywood and glass. Steel frame for the windows, perhaps, and open plan. It was a shock to most people when they saw it, but it made good magazine material. And magazines were constantly looking for that kind of story, because they knew it would have greater interest. So therefore, as I began the work, and architects would show their pictures to magazines, and as we looked before the early California Arts and

SHULMAN, JULIUS

Architecture was a forerunner of Arts and Architecture, which was acquired by John Entenza in the early forties. And so when he obtained the magazine, I was already being published throughout the country and several European countries, also by the magazine, Arts and Architecture, the original publishers. And so he continued using my pictures. Then when the Arts and Architecture case-study house program began–which was in the middle forties–I worked closely with the advertising manager of the magazine because A and B. A, there was no money for the magazine to perform the production of the case-study program without sponsors. B, there was no money for photographs.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yes.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Either the clients would provide the wherewithal, the homeowners. As in some cases, houses by prominent architects were already planned so they relegated them to the disposition of a case-study “label” scenario. Now therefore, the sponsors of the construction, the contractors–the building materials and the equipment suppliers–had to be approached and asked if they would be willing to participate in the program. And from the very onset, I worked closely with the advertising manager of the magazine, because I felt that this was a darned good cause, a good program, and it could be run in conjunction with the pictures I was already doing with architects and others, and I arranged with Bob Cron, who was the advertising manager, and he agreed with me, “Let’s take pictures of products of these companies that could possibly be sponsors. Give them free photographs. Show them publicity. So I went up and down the state with Bob Cron, showing pictures of products and structures of houses and commercial buildings done by the proposed sponsors. And it did bear fruit, because the upshot of all this was that they were able to build quite a few of these houses. They got companies to provide equipment and material–very generously. And that, together with the clients who owned the houses, helped to produce the program, and it became very successful in its own right.

Now that’s how I worked with Entenza. One shortcoming with Entenza was that although he was willing to work on this program–it was his idea–but the shortcoming of Entenza was–and it’s understandable to me because I felt the same way–architecture as we knew it then–consisted of a flat-roofed glass box. Entenza was fixated on the so-called International Style.

That’s simplifying it. And when Entenza chose the architects to do these houses… And by the way this came out very strongly down at MOCA [Museum of Contemporary art, Los Angeles–Ed.] the other day when I was there with Paul Karlstrom and the others–Joanne Ratner, and so on. They have models of all the houses. I said, “Paul, look! All these models have flat roofs. That’s Entenza.” He didn’t select any… Of course I think Paul had asked how the architects were selected, and I think I said that the architects were selected because they were pursuing the International Style. And [Raphael–Ed.] Soriano, as an example, would never, even if you chopped his head off, do a sloping roof.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: So it was Entenza’s idea of bringing ideas to Los Angeles, of promoting those European ideas in Los Angeles by selecting these very specific architects.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Well, wait. Let’s rephrase that, because were they really European ideas? We say, “Yes, they were International.”

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Well, that’s a historical question.

JULIUS SHULMAN: It’s a reality. It is reality. Now, architecture as we knew it in the forties and thirties, we had no precedent in this country. Really. The architects who were the offshoots of Richard Neutra’s training and disciplines had been imbued by the association with Neutra into nothing but flat-roof, flat-ceiling glass boxes. Now when they got into their own practice, they pursued the same design for they knew nothing else.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yeah, but Frank Lloyd Wright wasn’t necessarily _____.

JULIUS SHULMAN: Well, that comes later, that comes later. Now, Frank Lloyd Wright’s early houses–for example the Ennis House, the so-called master bedroom–has a pitched ceiling–the only room in the house that has it. So Frank Lloyd Wright would not turn against a pitched roof–or sloping… (He had sloping ceilings.)

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Yes.

JULIUS SHULMAN: From time to time. But it wasn’t part of his philosophy–as Neutra’s and the International Style people pursued. Therefore the Entenza discipline was based on what he saw and knew of architecture, and it had to be relegated again to the International Style. Out of this came a series of houses, which were very widely attended by the public when they were opened, but most people were looky-lookies. They were curious. Now here’s a house [Shulman’s own–Ed.], with us. This house was built, then occupied in 1950, and we opened the house to all kind of architectural educational tours. Fund-raising. The Radcliffe College, we had two tours, 750 people.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: Oh!

JULIUS SHULMAN: My God, we had people coming through the house by the droves in those early years.

TAINA RIKALA DE NOREIGA: [laughs]

JULIUS SHULMAN: People would come on weekends, and on Monday morning you would think that out of all these scores and scores and scores of people coming through this house, somebody would pick up the phone and call Soriano–because he was still living down here at the time–“Mr. Soriano, we saw the Shulman house yesterday. We sure liked it. We’d like to meet you and talk to you about doing a house for us.” Not one person ever called Soriano. And the result was that we learned quickly that this kind of architecture was not of the voice of the people.