“Let’s be honest. There is no such a thing as objectivity, and there is no action that is not in part driven by the subconscious, whether it be individual or collective.”

On March 18, 1998, Gilles Peress participated in a chat with students of Gretchen Garlinghouse’s advanced photography class at College Preparatory School in Oakland. Preston Tucker, Technology Integrator at College Prep, was College Prep’s liaison with the Connecting Students to the World project. Students prepared for the chat by studying Farewell to Bosnia by Gilles Peress (Scalo Publishers, N.Y., 1994). They also studied an online curriculum comprising Peress’s interview in the Conversations with History series and two web sites by Peress, one produced by New York University and the other by The New York Times.

Harry: Students I am pleased to introduce you to Gilles Peress, whose work in photography you know and have studied.

Preston: Gilles, welcome to College Prep, in a manner of speaking. Let’s begin with Ethan (DonJuan).

Harry: Ready.

DonJuan: Hello, Gilles. I was wondering how you became interested in this type of photography in the first place?

Gilles: When I was in school, I studied political science and philosophy. Given the fact that it was in France in the late 60s, a fairly verbose period both intellectually and politically, I came to a distrust of words and the codes attached to any description of reality. I saw a growing gap between words and reality. I had to find another tool to understand and formalize reality in order to stay sane and connected.

DonJuan: So do you attempt to justify reality in all of your photos?

Gilles: I am not interested in propaganda and didacticism. I am interested in trying through the process of photography to understand and make sense at least for myself of what is out there.

DonJuan: Cool.

Lesley: How purposeful were the groupings in the book (re: on several pages the images all had the same angle, or the same lens, or the same subject, and the book moved from the human activities to the tragedies of physical damage and death)? The internet version seemed very planned. The words and picture combinations seemed very poetic in comparison to the book.

Gilles: As you may have read in the appendix to the book, there was actually very little purpose in the groupings. The book was very much conceived as a raw take, a sequence of work prints, which found its design accidentally on the platen of a Xerox machine — two work prints at a machine, four for a double page, organized in a short burst of sequences on the same issues, the same moments.

DonJuan: Cool.

Gilles: Yeah.

Harry: Next question.

Forced Separation, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1993 @ Gilles Peress and Magnum Photos

“I have stopped being interested with virtuosity with the camera and the frame. I know I can do it. The only measure for me that matters is the transcription of experience.”

Ellie: Were you on a “mission” (assignment) or did you develop a personal attachment to the situation that caused you to be there to shoot? How were you involved with the subjects you photographed?

Gilles: As an old anti-authoritarian, I am very bad at fulfilling missions, especially those framed by others. It is all a very personal thing.

Matt: Did you travel alone or in a guided group? And if it was a group, how did that influence what you could see and what images you could take pictures of?

Gilles: I am very bad at groups. I essentially travel alone or with companions I would meet along the road in the haphazard drift of a country at war and conflicting individuals and needs. People come and go. I meet you today and lose you tomorrow.

DonJuan: Have you had previous experiences traveling in countries during wartime —

“If you don’t remember history, as Marx states it, you are condemned to repeat it. Marx says the second time history repeats itself, it is a farce. I disagree. I think it is a tragedy.”

Gilles: Juanito, I am 52 years old, and I have been traveling for at least the last thirty years —

DonJuan: — and if so, have you previously taken other photo essays?

Gilles: — on any kind of road in any weather, in any circumstance. Question answered?

DonJuan: Yeah.

Johanna: This might be kind of off-topic but, as a photographer, how do you frame your images? At what point are you satisfied with your work? What do you consider good photography?

Gilles: Johanna, I have stopped being interested with virtuosity with the camera and the frame. I know I can do it. The only measure for me that matters is the transcription of experience. It is the moment where you say “This is it. This is how life is. This is how that moment was!”

Laura: When did you realize that you wanted to pursue photography as a profession rather than a hobby?

Gilles: [When] I realized the limits of words as a practical tool to understand and formulate the texture and structure of reality.

Preston: Ellie has one final question.

Ellie: What is it like to come back after being in Bosnia or Rwanda and photograph in a “normal” situation?

Gilles: Ellie, It is all a continuum of experience. I don’t see a gap between one situation and the other. It is all about a struggle between order and chaos in varying proportions.

Gilles: Thank you.

DonJuan: Later, Gilles. Thanks for chatting.

Gretchen: Hi, Gilles, this Gretchen Garlinghouse, the teacher of this photography class. I want to say your work has inspired wonderful conversations about photography — raising technical, professional, ethical, personal, and communication issues. We all thank you for giving us your time and photographic vision.

Harry: Students, thanks for some great questions. Thank you, Gretchen and Preston, for making this session possible.

Johanna: Thanks a lot from me too.

Ellie: Me too.

Preston: Thanks, Harry and Gilles, for including us.

Harry: Students, Gretchen and Preston you are invited to a reception for Gilles tomorrow at the Human Rights Center at 4:00. Preston has the info in my last e-mail.

Christian: Bye

DonJuan: Peace out.

Harry: Bye-bye, College Prep, and thank you.

DonJuan: Yeah.

“I have to point out to you that there is no clean, perfect human activities; that even doing nothing is doing something.”

Rachel: M. Peress, almost all of your photos include people. Are people most interesting to you or were there few interesting non-human subjects? Was this a personal choice or one that came with the assignment? Do you have a favorite piece in Farewell to Bosnia?

Gilles: Rachel, last things first, as usual. I don’t have a favorite piece in Farewell. It is a whole experience for me, or a transcription of a whole experience. As far as people in the pictures, because it is a very human situation, involving real human beings, it is self-evident that people would be an important motif in the images themselves. However, one of my personal discoveries through this project has been about the nature of still lifes as very powerful metaphors of human events, as very powerful representations of history’s imprint on the physical world.

Johanna: You’ve said that the project was very personal to you as I would assume it would be when documenting such raw emotion. You’ve also said that you can meet someone one day and they’ll be gone the next. What were your relationships with your subjects like? Personal or distant?

Gilles: War is about dislocation, fragmentation — dislocation of communities, of families — fragmentation of bodies, which means that somebody next to you one minute is gone the next. So all relationships are in the moment. In some ways, there is a pathetic beauty to those relationships where everything is said, everything is given on the moment, knowing there is no tomorrow. And that goes as much for the relationship between the photographer and his subject as for any relationship between members of the same family, the same community, lovers, friends, and so on.

Christian: You seem to have a detached approach to war (and rightly so) but as you took pictures, did the situation, people, etc. begin to affect you? Or did it not?

Gilles: Christian, I don’t see where you see the detachment.

Christian: As in not being directly involved.

Gilles: I think you have a misconception as to war being totally discontinuous human experience from other states of being such as peace and so on; discontinuous from other human experiences and state of affairs.

“War is about dislocation, fragmentation — dislocation of communities, of families — fragmentation of bodies, which means that somebody next to you one minute is gone the next.”

Rachel: Not getting emotionally involved?

Gilles: Von Clauswitz, a theorist of war, describes war as the continuation of politics through other means. You could approach the same notion of continuity from a psychiatric, psychoanalytical angle. War has been part of human experience from immemorial times. The sooner we acknowledge it, stop romanticizing it, the sooner we can start to bring it under a more powerful rationale that has to do with international justice, international tribunals, the laws of war. The sooner we are able to accept its existence as normal, the sooner we will be able to identify the abnormal behaviors that constitute crimes of war. Then we should be able to reduce the abnormality of the specifics.

Lesley: About halfway through the book, on a four-page spread, there is a picture of a sobbing woman surrounded by photographers. This is the only picture in your book that includes a view of other documentation of the war. Why did you choose to take this picture? What were you trying to portray? Do you see yourself as one of the photographers surrounding her?

Gilles: Lesley, of course I have to be honest about myself, about some of the more distasteful elements of my activity. I have to point out to you that there is no clean, perfect human activities; that even doing nothing is doing something. And in most cases, it is more criminal than doing an imperfect act.

Rachel:So is it kind of a confession?

Gilles: Rachel, any work you do has an element of confession and autobiography because you have to be honest to the reader that what they are about to see, hear, or read has gone through the distorting prism of one individual’s subjectivity and has also been shaped by the limitation of any given media, be it photography, literature, cinema — which are all by essence imperfect at transcribing experience.

DonJuan: Speaking of individual subjectivity, do you attempt to keep as high a level as possible of objectivity, or rather let your subconscious direct you as it will?

Gilles: Let’s be honest. There is no such a thing as objectivity, and there is no action that is not in part driven by the subconscious, whether it be individual or collective. I think the sooner you acknowledge the subjectivity of any human communication, the sooner you can enter into a methodology of self doubt whereby through a succession of subjectivity and doubt you can keep reexamining your successive perceptions and in the process, over the distance, obtain some form of objectivity resulting from acknowledgment of your condition as subjective, tempered by doubt.

Rachel: M. Peress, could you please explain the “you are damned if you remember” passage in the internet version?

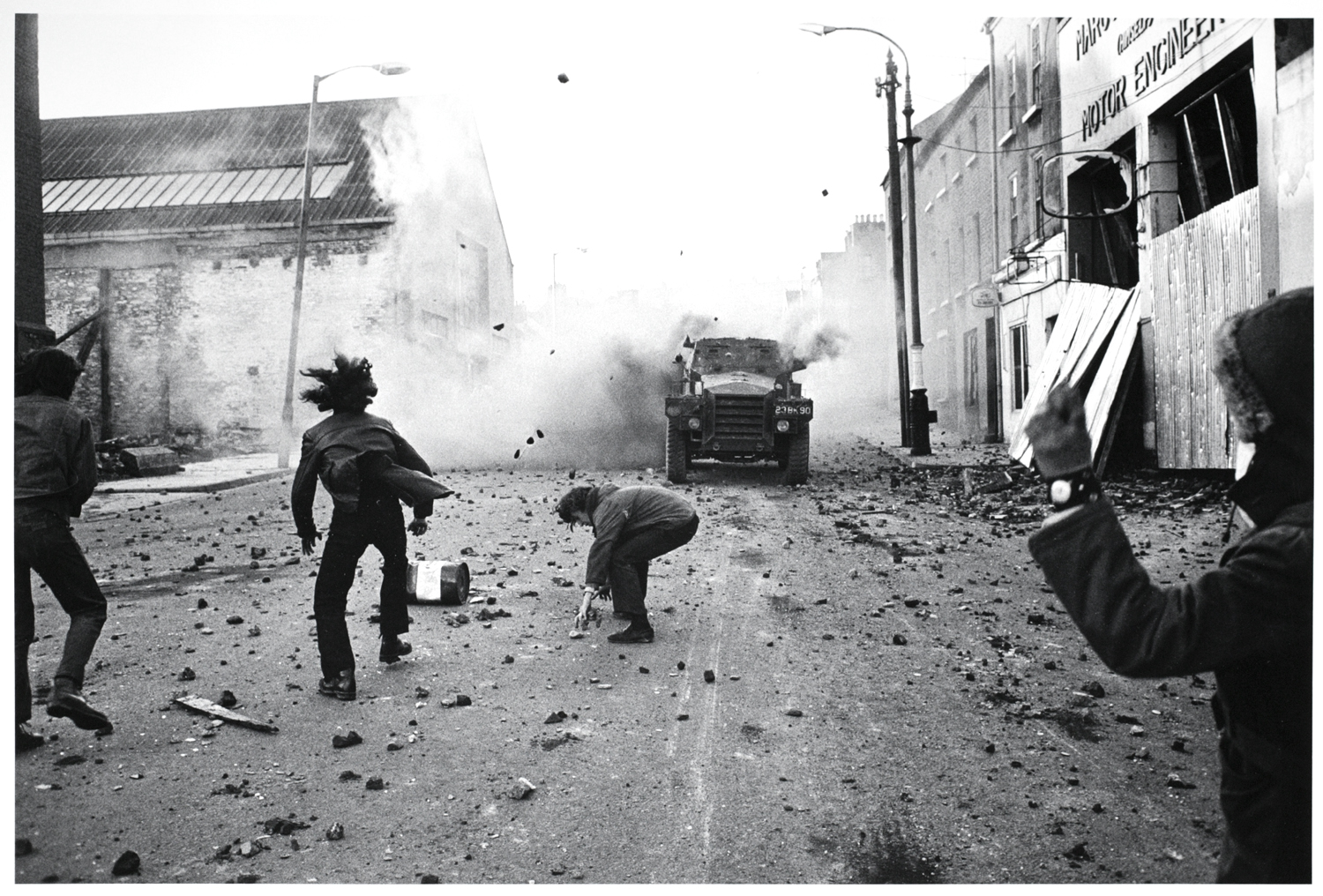

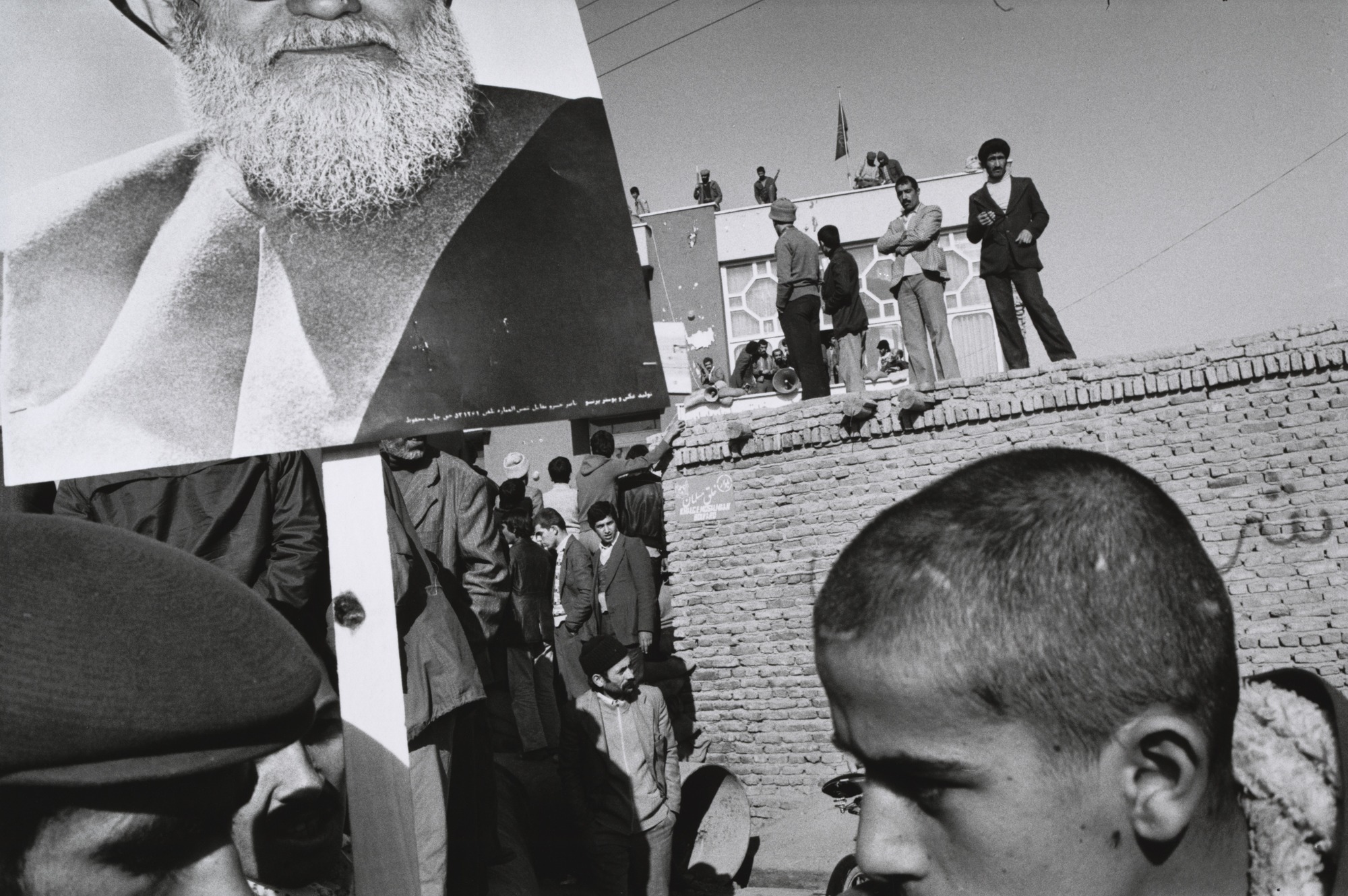

Gilles: Rachel, it is about the curse of history. If you don’t remember history, as Marx states it, you are condemned to repeat it. Marx says the second time history repeats itself, it is a farce. I disagree. I think it is a tragedy. However, if you are “aware” of history, given our current structures of transmission of history — all history from our parents, slanted nationalist histories through our curricula — there is compelling evidence in fairly ritualized societies such as Northern Ireland, former Yugoslavia, etc., that along with this history that is being passed to you, images, mental images, are being passed on to you. Images that leave you in a powerless horror in the middle of the night. In order to be able to deal with these images, you have to act them out; therefore repeating the horror of the past. It is the stories that were told to the children of Yugoslavia at bedtime that are directly responsible for the re-creation fifty years later of images of similar patterns, tone, and emotions today.

Gilles Peress joined Magnum Photos in 1971.

All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher