“Killip was a human first and an observer or lucid chronicler second”

Chris Killip is known for his immeasurable and singular vision of Britain during the 70’s 80’s and 90’s. To place emphasis on his work in a genre-fied manner would belittle his and its true humanity and potential. Killip was a human first and an observer or lucid chronicler second. In my personal estimation his book In Flagrante and its subsequent version In Flagrante Two along with Seacoal are two of the more enduring works of the past 100 years of publishing within the medium of photography. Once you crack the covers of these works, it is hard not to be left with a sense of urgent sympathy for the people and the timeframe in which it was produced.

Chris Killip-In Flagrante Two. Youth On Wall Jarrow Tyneside. Steidl

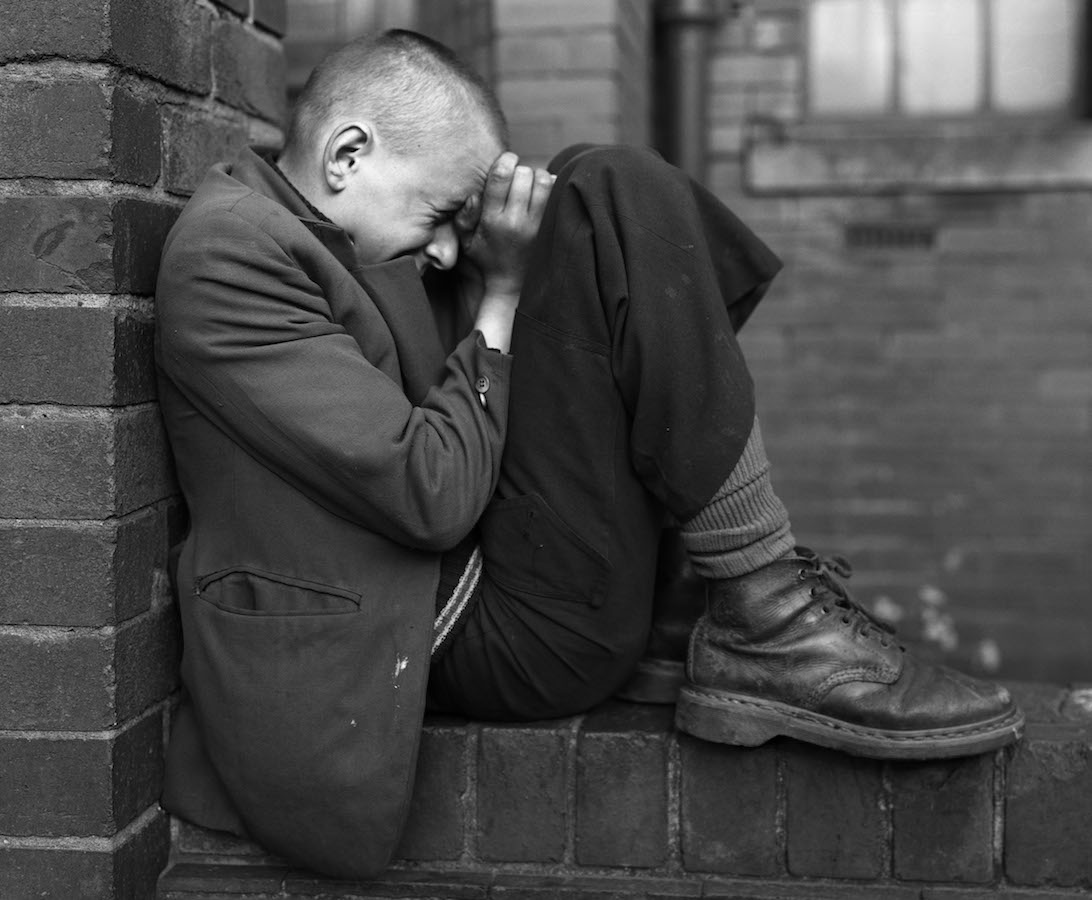

Within both titles, it would be hard to eliminate the Thatcher years in Britain from the frame, but it is possible to move the conversation to a more general state of empathy when you reflect on Killip and his insightful references to what it means to be a human of the post-war Twentieth Century. You do not need to be British to see the conditions that Killip was reflecting on in the work, nor do you need to be considered a documentarian to make work of this magnitude and have it resonate-in fact, it may be better if one does not associate the product of such efforts to this term. If you are even slightly bemused or interested in the end of industry and the slide from manual jobs to a neoliberal work economy that emphasises data over effort and people, then you will be aware of the effect that Killip’s work has. You need not build a ship to understand the implications of its potential for its cargo.

Chris Killip-In Flagrante Two. Father and Son Westend, Newcastle. Steidl

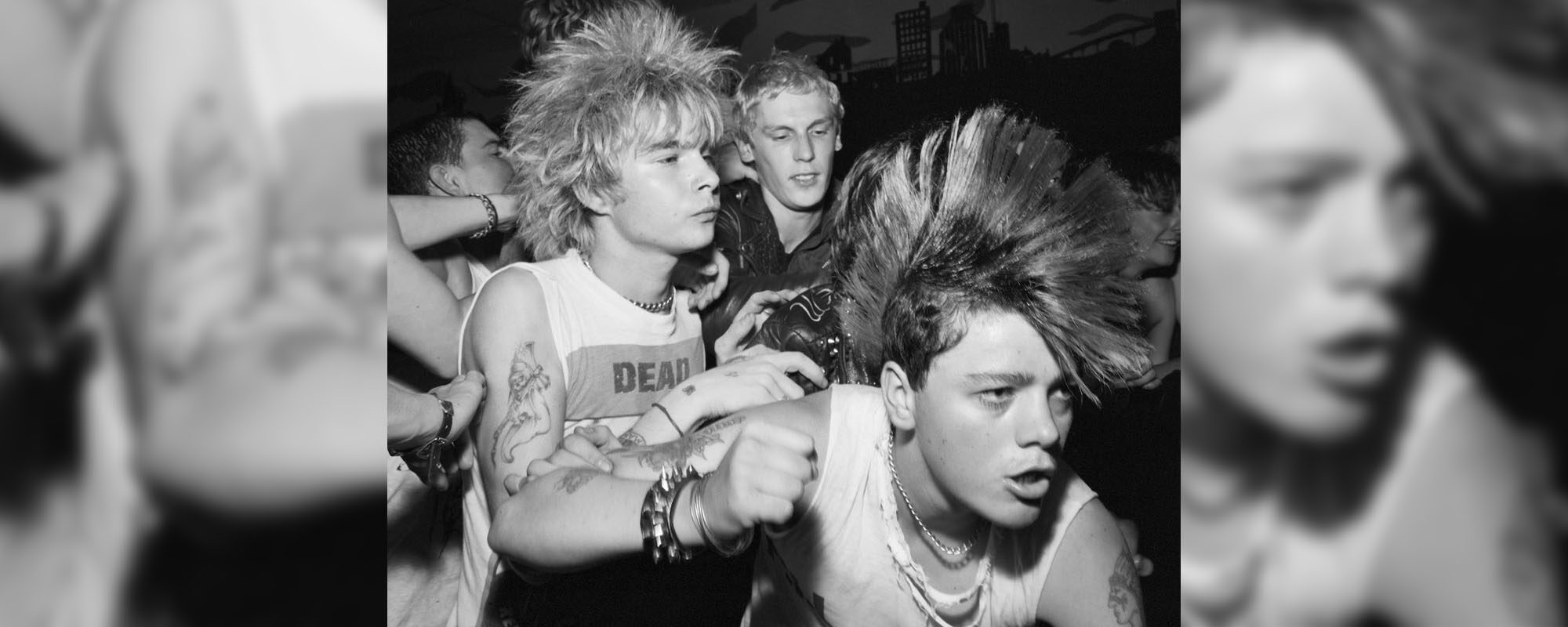

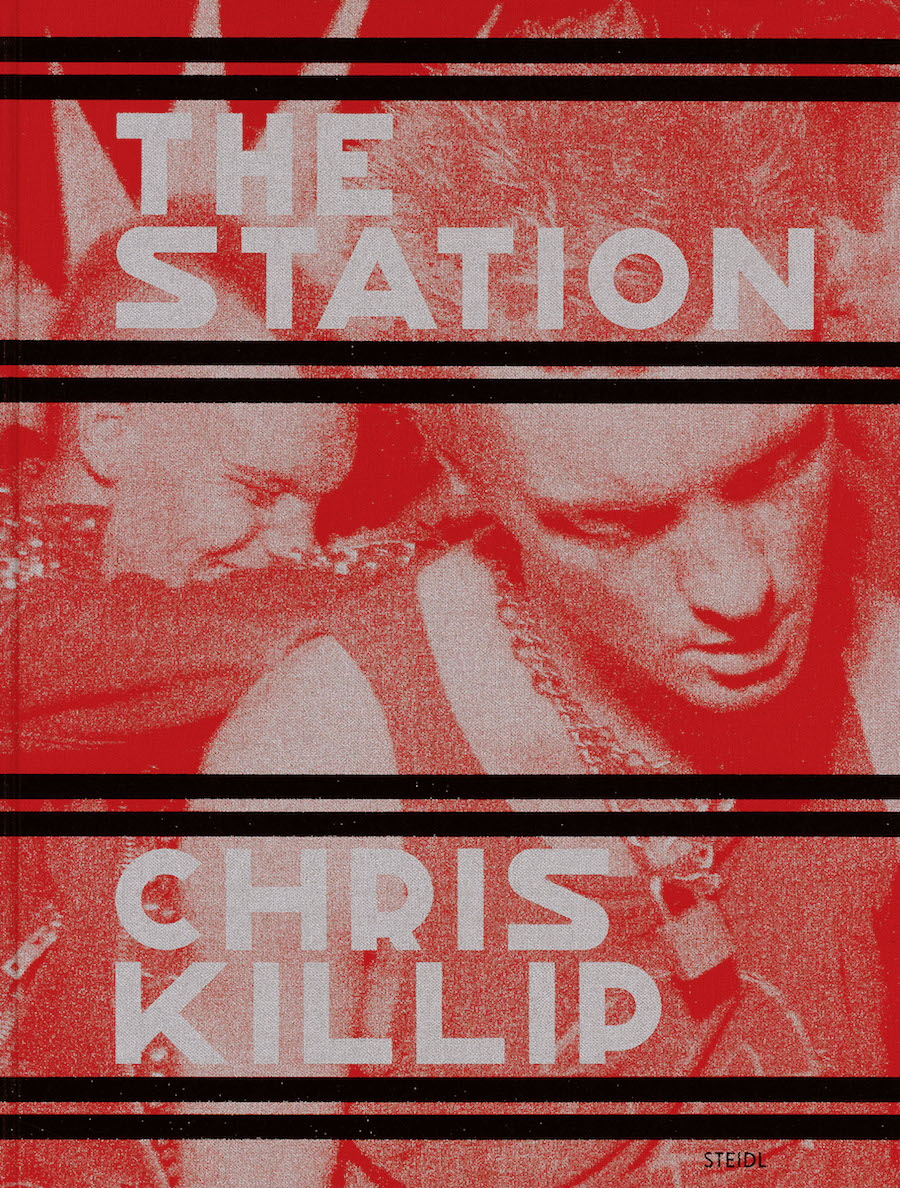

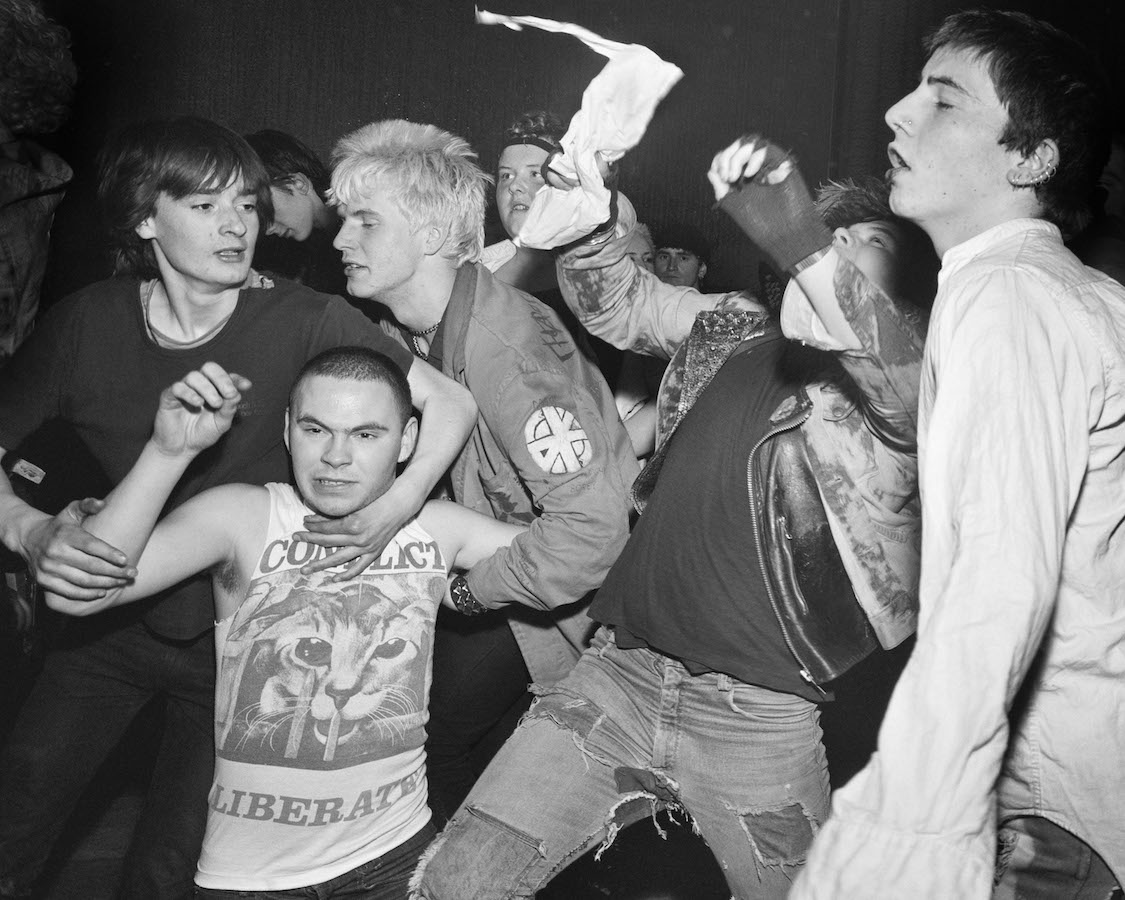

The Station (Steidl, 2020) is a similar affair to Killip’s earlier works in some ways. There is an emphasis on the marginalised Gateshead community of anarcho-punx that frequented a local venue called The Station during the mid-80’s to catch gigs from Amebix, Napalam Death, Godflesh and the list literally goes on and these names are exquisitely printed in the end papers of the beautifully-designed (with a nod to Mendelsohn’s Amerika) oversized book. Whereas as earlier Killip titles reflect sober open spaces in which we can examine the social weave of his interest, The Station provides something more jarring and urgent. Bodies are complicated throughout the frame and the same dissatisfaction or bittersweet and somber motifs that feature in Killip’s earlier books are replaced with a new generation of youthful, predominantly male bodies bursting with pierced and inked energy and to be fair “anger is an energy“. Instead of looking on Skinningrove with its taciturn expressions of lament and approximate familiarity, The Station represents a pulsing entropy within each frame. Everything that cannot be enlisted as a closed system of rules ends in disorder and in that disorder one can achieve a solvent and necessary expenditure of energy resulting in the fracturing of the previous closed system.

Chris Killip-The Station. Steidl, 2020

This is an important book for examining Killip’s wider career and there are some incredible anecdotal moments that you can find Chris speaking about the experience of turning up at The Station in his suit amongst the sweat, smoke and off-license beer cans to make these images with his big camera and its almost imperceptible use in such a small and chaotic space. The results are somehow unnatural as if some misplaced and re-dressed white Roman statues had come alive and decided to make the statue of Laocoon mosh to Chaos UK. The Doc Martins up-heeled and nearly kicking the lens of Killip’s graceful 4×5 large format press rig trapped in the silver nitrate of ages to come, all witty unrest and dissatisfaction congealing into the very fibres of this book. It is a beautiful tome to own and befits the ever-progressing appreciation of Chris’s life and work and the healthy re-examination of Britain on the cusp of yet more change.

Chris Killip-The Station. Steidl

“The results are somehow unnatural as if some misplaced and re-dressed white Roman statues had come alive and decided to make the statue of Laocoon mosh to Chaos UK. The Doc Martins up-heeled and nearly kicking the lens of Killip’s graceful 4×5 large format press rig”

The following excerpt is taken from the author’s instagram account and survives as a Eulogy of sorts for Chris who passed on last week. His work and kindness, his observational prowess and unending brilliance have paved the way for many people in our medium and is still finding new eyes and hearts to turn towards something greater than ourselves.

I had the good fortune of speaking with Chris Killip early on in the year for Nearest Truth. We had arranged to speak on his book The Station, an incredible tome that Steidl put out earlier this year which now seems like an eternity ago. About 40 minutes into an already technically crumbling, but fascinating conversation due to connection issues, we decided to try again later and did so maybe three weeks forward only to have the same issue occur with the software bungling up. This has oddly never happened like this since. I had recorded perhaps another half-hour and suggested we try again if he had the time. He said he would think about it, but also mentioned that time was becoming precious and had informed me about the situation regarding his health. I checked in a couple of times just to say hello and maybe attempted to keep things light and positive.

We spoke about quite a bit in both conversations. Much of it related to The Station and the design of the book and our man Craig at Café Royale books who has been making Chris’s works available in powerful zines. Chris had spoken about being in The Station and how odd he must have looked in an anarcho-punk club in his suit and with a big camera, but one of the parts of the conversation that we spent time on was about an image of a young boy named Simon, which you see here…

Simon Being Taken out to Sea for the First Time since His Father Drowned, Skinningrove, North Yorkshire, negative 1983; print 2014, Chris Killip, Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of Steidl and Chris Killip. In Flagrante Two

We spoke about the power of this image, the boy’s story and Chris’s return at points to Skinningrove. It was an incredibly powerful moment for me. I look at this photograph, with the context provided and still feel the tentacles of something inexplicable making their way up my spine and into the back of skull, where the brain pan fuses to duramater. Of course, part of the tragedy in all of this is that the episode and talks with Chris are not in good enough shape to publish for Nearest Truth and though that is the case, what I can tell you is that the personal learning that I accrued through this simple and gentle series of conversations with Chris have changed my view on what photography, despite all of its problems of representation and politics, can do with empathy.

My condolences go out to his family, in particular to Matthew who I have also spoken with for NT. With artist like Chris, our personal world can be expanded towards something more universal, bright and still be mired in the obtuse problems that the world serves to us. It is what we do with the problem and how we navigate difficult territory that makes our efforts humane and widely sympathetic. Chris’s work exemplifies all of the best that we can aspire to in times of difficulty and blight. I want to simply say…Thank You, Chris.

]