“This ‘gendering’ includes everything from one’s awareness of their own individual body, to global political and social issues (the feminine pose, the masculine blue colour, the ‘masculinity’ of war)”

Mayumi Hosokura’s New Skin begins with a single quote on its inside cover. It is a quote by Donna Haraway, from her 1988 essay ‘Situated Knowledges’.

“Gender is a field of structured and structuring difference, in which the tones of extreme localization, of the intimately personal and individualized body, vibrate in the same field with global high-tension emissions. Feminist embodiment, then, is not about fixed location in a reified body, female or otherwise, but about nodes in fields, inflections in orientations, and responsibility for difference in material-semiotic fields of meaning”.

Torn from context, it is difficult to understand; to those unfamiliar with gender theory and poststructuralism, this kind of writing is almost impenetrable. It’s necessary to roughly translate this framework of thinking into a more accessible form of English:

“The thing we call gender is a social structure that is built up by differentiating and categorising objects, individuals and behaviours into loose conceptual frameworks. We use these conceptual frameworks to navigate the world: to label people’s appearance, their actions, and even their ideas by assigning gender values to them. These all operate through differentiation. This ‘gendering’ includes everything from one’s awareness of their own individual body, to global political and social issues (the feminine pose, the masculine blue colour, the ‘masculinity’ of war). In feminist terms, this means that the experience of one’s own gendered body is intimate and lived, but also negotiated in reference to wider societal frameworks. Gender, in other words, isn’t just defined by the way you see yourself, or by your immediate circumstances, but also how your ideas around gender exist as points of reference relative to those in the wider world. Your own embodied experience of gender, and your experience of the gendering frameworks that structure the world, can be two very different things, but exist within the same conceptual space that is Gender.”

No other context is provided save for another, similar quote on the back cover.

To those unfamiliar with the paragraph, Hosokura’s quoting Haraway will likely function as a word-cloud intended to prompt thinking about “gender and technology”. This is supported by press texts, which – though not a part of New Skin physically – still exist in the wider context that the book is spoken about, priming prospective buyers to think about it with particular readings in mind.

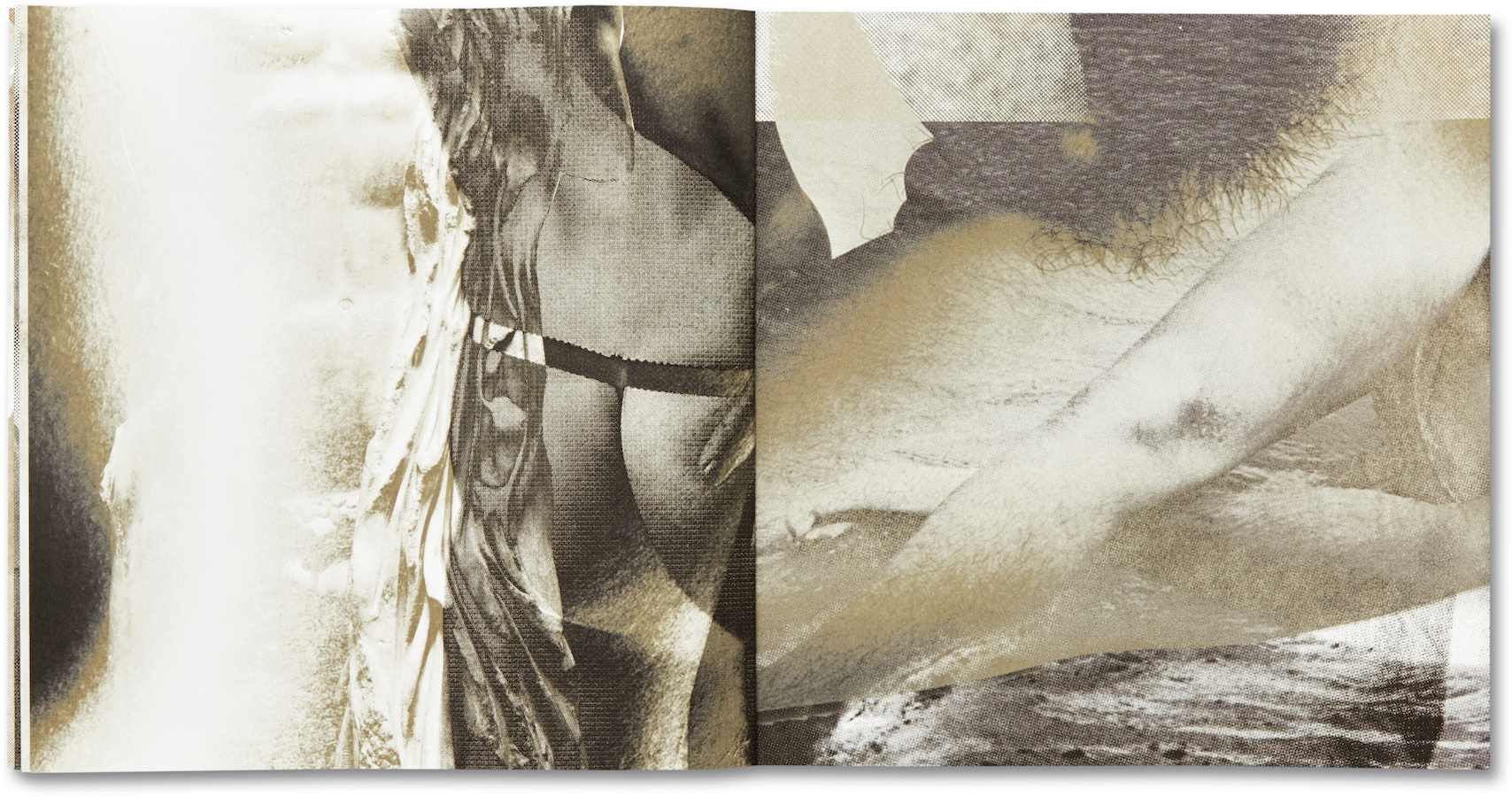

“We are told in some press texts – but not in the book itself – that the denim, body hair and non-statue limbs are from old gay magazines, which we may regard here as offsetting the body’s flesh with the statue’s figure”

Haraway argued for breaking down objective ways of seeing, of pushing beyond binaries and considering the body in relation to other objects and forms. To create New Skin, Hosokura produced a large digital collage, cutting it up into square selections and re-ordering them in book form. Images of cut-and-pasted flowers, statue limbs, mobile phones and messed-up hair all layer and blend into one another, often phallic and difficult to immediately identify. We are told in some press texts – but not in the book itself – that the denim, body hair and non-statue limbs are from old gay magazines, which we may regard here as offsetting the body’s flesh with the statue’s figure. The digital cutting and enlarged offset-print dots in New Skin interlace with subject matter like old marble statues and cellphones to pull on a vague historicity.

This is coincident with a recent trend in photography, to gesture at broad concepts without really exploring them. In this way, a particular kind of object or location will have its signifying potential limited and fixed into a more simple form, e.g. a photograph of a cell phone may be used to represent “technology”. Such projects use associations brought out by framing texts to evoke the feeling of a concept rather than building it up through demonstration. In some cases, like in Sophie Calle’s Because, this can open up an interesting game of playing with signs and symbols, but in other cases it results in a rigid framework of meaning that appears to increase nuance or complexity while actually reducing it.

New Skin seems to tie these signifiers together as much as possible, building up a noisy system of a very limited number of subjects which blur into one another formally, but which are conceptually quite segregated. The flower appears phallic and limb-like in the digital noise and will probably make you pause the first time you see it, but our awareness that it is a flower, and its position as something perceived as “feminine” within both cultural and visual discourse is really encouraged.

We can imagine it differently, as Hosokura may intend, but fundamentally, the antiquated ‘flower as signifier of femininity’ message is reinforced, rather than challenged or given an alternative from the beginning. In trying to suggest gender through these different subject matter, New Skin fixes their potential meanings in place, relying on an awareness of a complex philosophy in regards to gender to do the legwork.

This might be a strength to those who haven’t had the opportunity to engage with these ideas and who are able to understand Haraway’s quotes, but will be very familiar for those already relatively well-versed in them. The noisiest, most difficult-to-interpret areas of the collage are where it is most successful, and also most ambiguous. Conversely, the most visually identifiable aspects seem to be literally pulled from Haraway’s quotes e.g. “stitched together imperfectly”, where it begins to feel as though New Skin has been made in an attempt to demonstrate theory rather than build from it.

The message in New Skin is relatively obvious to those who know it and dense to those who don’t. The only real framing device to the book being two decontextualised quotes from a continental philosopher, New Skin sustains the impenetrable and exclusionary nature of much of the language used by the writing of that period.

New Skin’s design is particularly attention-catching, and really beautifully done. Though the spine is bound like any other book, its pages are like a traditional Japanese book, folded in half and bound into “pockets”. It has been printed on both sides, but being folded in half, you must open up the pages and peer inside. The thinness of the paper means that the outside print often shows through on the inside, encouraging thinking on the hidden identity and the surface appearance. There’s a real temptation to rip the pages at the edge and look inside properly, opening the unseen interior up and giving it equal weighting with the exterior, rather than allowing one side to binaristically hint at the other. A far more interesting intention may have been that we look inside using our phones. Not only is the wide-angle lens of the phone camera perfectly adapted to peering inside difficult-to-access spaces, it resonates much more strongly with allusions to thinking with technology, and approaching gender with technology as a solution.

The whole book bends under its own weight as you handle it, adding to this physical experience. But were the ink used on the paper itself heavy and raised, the printing itself would really complete these design choices, and lend it a tactility that would crystallise the textures of Hosokura’s collage. Instead, the smooth printing is beautiful, but doesn’t let the physicality of the book or the visual texture of Hosokura’s images come full circle.

New Skin then gestures towards the ambiguity and potential of gender in relation to technology, but in a way which relies on the viewer to rigidly categorise its various subject matter according to traditional binaristic notions of gender and signification. It has been argued elsewhere that New Skin breaks down these rigid boundaries, and although it does this aesthetically, its conceptual core actually reinforces such boundaries.

Mayumi Hosokura

MACK

https://mackbooks.co.uk/products/new-skin-mayumi-hosokura

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Callum Beaney, Images @ MACK)