“Do objects have a relationship to each other outside of human relations? Object orientated philosophers contend that they do, critiquing the Kantian philosophical tradition of anthropocentrism that places objects as subordinate to humans and their cognition.” – SS

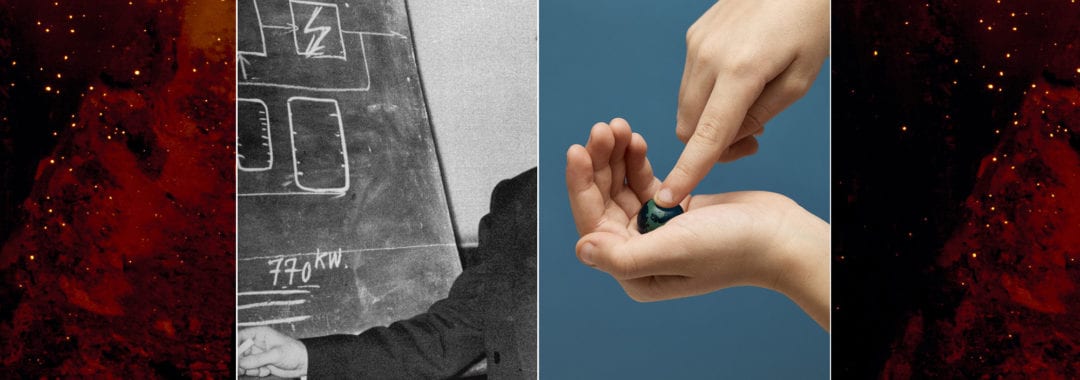

Do objects have a relationship to each other outside of human relations? Object orientated philosophers contend that they do, critiquing the Kantian philosophical tradition of anthropocentrism that places objects as subordinate to humans and their cognition. I wonder about this thinking of the latent reality of the objects and documents in Felicia Honsksalo’s book, Grey Cobalt, based on her grandfather’s work archive. As a geologist, he collected and recorded his work meticulously, revealing a life of research, experiments, specimens, samples and equipment. None of this meant anything to Felicia, only that it was compelling enough to become part of an enquiry into the materials she sifted through to learn something of her grandfather, whom she hardly knew in person. Grey Cobalt is published by Loose Joints and the following conversation took place over email in February and March 2019.

SS: Can you tell us about how this project came about and how this relates to your wider practice and interests in photography?

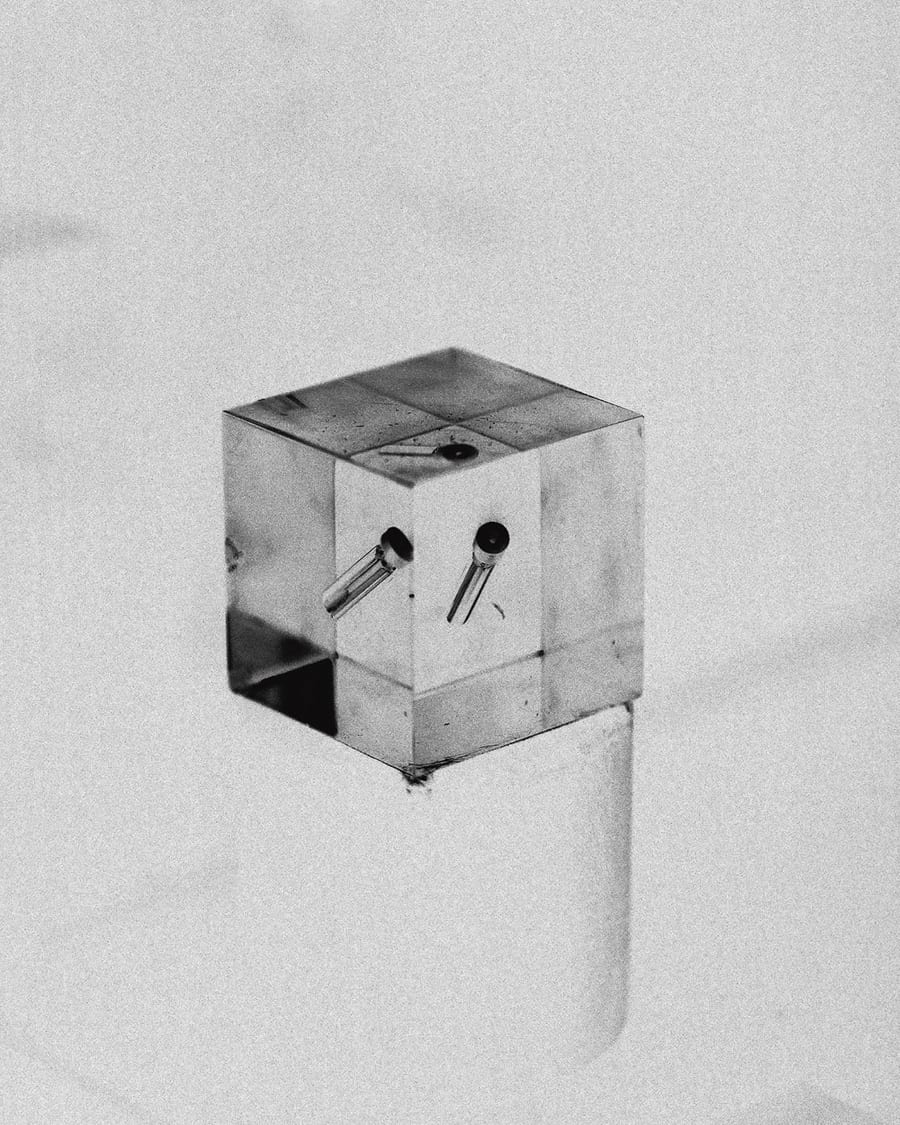

FH: My story began with objects. When my grandfather died, I lived in London, and was not present when his belongings were divided amongst relatives. I had very few washed out and faded memories of him from my childhood, but even then, he had seemed to be an elusive character, very different from my grandmother, with whom I had a close relationship to as a child. In my family home, in which my parents still live, unfamiliar objects started to appear, and on one visit from London I opened the attic doors to find boxes and boxes of books and papers. Slowly I started rummaging through them, in search of an idea of the person that had passed away. That perhaps these papers or things could explain to me what had happened, who he had been. In my mind, these pictures of minerals, medals, open cast mines, furnaces, factories, miners, steel sheets and rolls were marking a path to a world in which I could find the person that had disappeared. I started to read about metallurgy and enrolled on a course on geology. I visited museums, looked at core samples, went to factories, studied the intricate drawings of furnaces, trying to form an image in my mind as to what this was all about.

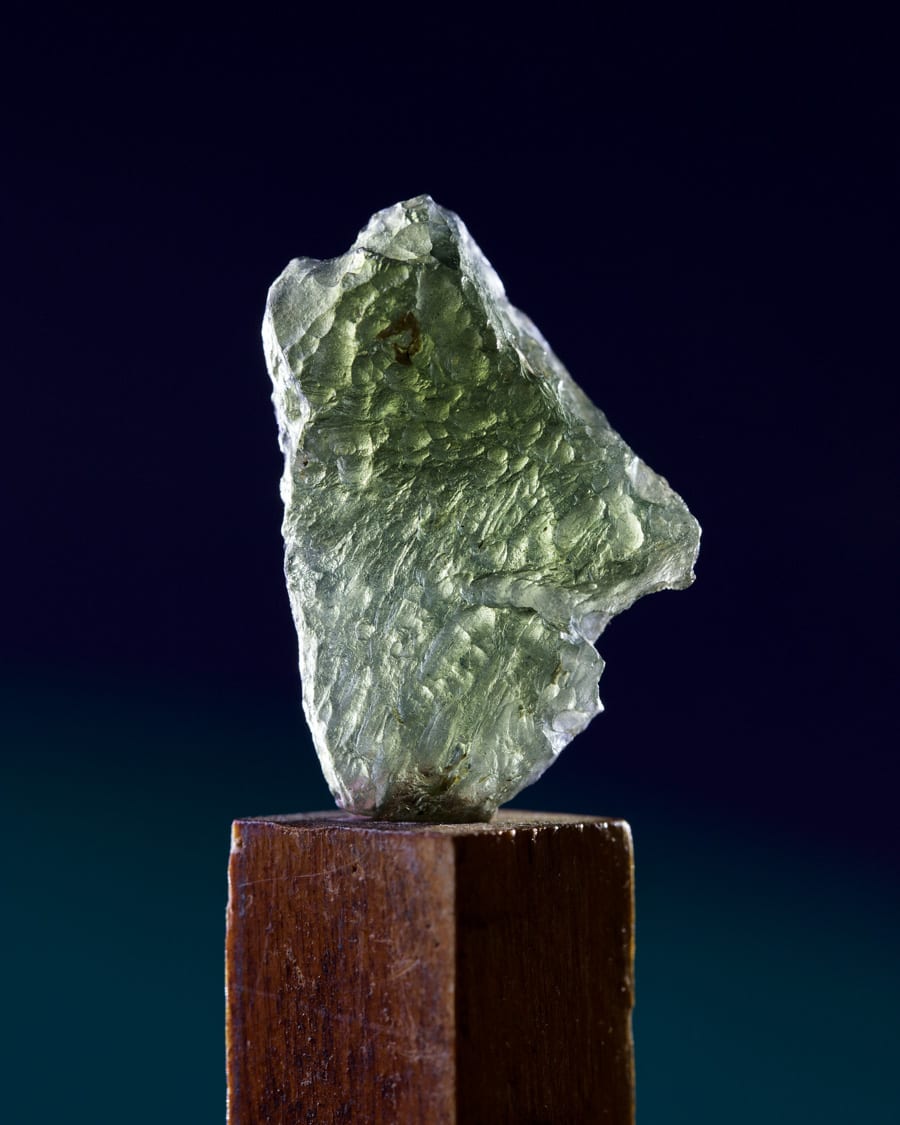

If I had no grounded memories of the person who had passed away, did he really exist? Could I find the memories somewhere else? Could I create them? I started looking at the objects in a different way, organizing them into groups based first on intuition and then on a system I created. They became, for me, souvenirs from the past, souvenirs that had outlived their owners. I started to see a pattern emerge, in which specific artefacts seemed to hold inside them a hidden narrative, as if they were silent about the story I wanted to discover. I catalogued all the objects by taking photographs of them, after which I regrouped them according to how they appeared to me. Through a language I felt was hidden inside the objects, I wanted to see if these objects could reveal something through my images.

Having never known him, remembering for me is an act of reconstructing through imagination not only a person, but a world that once existed. Being a man dedicated to his work, the inherited artefacts were not perhaps the usual heirlooms. In the process of creating metals, that are vital to our materialistic existence, rock matter is poured into a furnace turning it into molten matter. There is something captivating about this act, as it is precisely in this state that the earth once was, and how the core of the earth still is. Whereas geologists use rock layers to read the timeline of the earth, in a furnace, we fast track through all that history, back to the start of our time. I like to think of the work as a capsule of space and time like that of a cabinet of curiosities, where the disparate collected objects help one form a tactile experience of a lost world. And like all collections, they evoke an ever-present absence.

What started out as an act of mourning, turned over the years into a complex set of questions through which I tried to understand and investigate the possibilities of making a portrait of someone lost to the sea of time. How could I make sense of, primarily a person’s death, but also, and maybe more importantly, that they had once existed, lived a life, but had now disappeared. In an interview with Christian Scholz, W.G. Sebald verbalises my main concerns in a very precise manner:

“You cannot imagine what it is, this slow dissolution of life over many decades. And that is something absolutely monstrous (Ungeheures) to me: having to witness this and having to take into account the possibility that this real person who is now, in the year 1999, let’s say eighty-five years old, back then supposedly was only twenty-two years old. Is something like that possible? Can we get that into our heads? What do we do with this information?”

By exploring these ideas through photography, the work is also a commentary on photography itself. Through very minimal visual information, I try to unfold and make use of this impulse we have to grab hold of that which is evanescent by making a permanent record of it, and the failure of making that record. What is held onto through a photograph, is no longer the disappearing object itself but something that appears or becomes visible in the moment of its vanishing: as it were, the last glance that it casts at us, or the last glimpse of it that we can catch.

“What is held onto through a photograph, is no longer the disappearing object itself but something that appears or becomes visible in the moment of its vanishing: as it were, the last glance that it casts at us, or the last glimpse of it that we can catch.” – FH

SS: There is an interesting relationship here between the transience of human life and the permanence of matter and the hope that something of your grandfather can be recouped from within the objects and documents of his life. I am interested in the process of activating this archive which for me greatly includes the act of sifting through his belongings, making sense of them, research, learning and photography, the creation of a new archival order, for you, one day to be passed down to your relatives. For me this act of activation of this material goes beyond its photography. It is a relationship to absence and to loss, the belief that in the material we can find access to the spiritual. I love this belief in the power of objects, aesthetics aside, it is cosmological at the atomic level; harking back to the fact that all matter was created in the origins of the universe. We are all made up of the same matter and it is our spirit that resides within matter, so looking at objects to find a person doesn’t seem at all absurd, does it?

FH: This is really interesting, because on the one hand I agree, that yes, at times it seems as if the spirit of someone resides within matter, but then when I was working on this project, I came to look at it from another angle, that rather we place that spirit within the object, we project ourselves onto them and anthropomorphize these independent things. The object itself is something else, has its own hidden trajectory, and agency, which we know nothing about. People have throughout history had a need to place objects near the final resting places of the dead, from the paraphernalia placed inside tombs of Pharaohs in Ancient Egypt to the votive offerings laid along graves in Catholic countries. What fascinates me, is that these objects have had the occupation of keeping the dead close to the living, but they have also been placed there in order to gain favor with supernatural forces. Grave goods are still placed into caskets for example in Finnish secular society, and they are seen to serve the purpose of aiding the journey of the deceased on its migration to the unknown. But then at the same time these objects really only serve us, the living, in helping us deal with the death of someone close to us. An archaeologist from the University of Helsinki told me once how funeral homes in Helsinki have had problems with mourners placing mobile phones into caskets, as the batteries explode in the furnace of the crematorium, causing irreparable damages. The problem has been solved by advising mourners to take out the battery before dropping the phone in with the deceased. I see this mobile phone as being something that eases the pain of the mourner, rather than easing the afterlife of the one who has parted, but who knows maybe I’m wrong. I do still wonder, what is it that objects hold, that has made them the laborers of memory and mourning? Of course, one aspect is the tactile function, objects are something we can hold and caress, or kick, something we are in active relation to, rather than the more complex feelings related to mourning, death and facing our own dissolution.

“I am interested in the process of activating this archive which for me greatly includes the act of sifting through his belongings, making sense of them, research, learning and photography, the creation of a new archival order, for you, one day to be passed down to your relatives. For me this act of activation of this material goes beyond its photography. It is a relationship to absence and to loss, the belief that in the material we can find access to the spiritual. ” – SS

SS: What do you feel you learned about your grandfather and his world in this project?

FH: My grandfather’s story is of course the one that many will attach themselves to, but I would find it important that people also try and see the context as something involving a much larger narrative, like you mentioned in your reply. During my process I was interested in how these independent, witness bearing entities communicated, to me, aspects of this complex relationship between my own, fleeting, disloyal memories and these almost eternal, solid forms that had seen so much, yet withheld all that information. I would touch their material surface and by investigating the circumstances in which they were born, questioning the landscape they were from, I came to recognize that they have capacities to interfere and disrupt historical moments. That was a really important turning point for me. It is not a purely human history that I want to convey in the book, rather a much larger narrative that humans usually overlook. For me that was really essential, to see these inanimate objects as having agency, and having them telling their story, if you can say that.

These encounters with the landscape and the objects driven out from the depths of the earth made me question the usefulness of depicting a human history, and rather I started to be more and more interested in the hidden history within these objects and places. Take for example Nickel, there is a town in Russia named after the hard and ductile metal. It’s very valuable in modern industry, but it is also an essential nutrient for quite a few living things, and furthermore occurs in meteorites that fall from the sky. Some believe life came to earth on these falling rocks containing nickel. The biggest reserves are believed to be inside the earth, at the centre, that is a like a massive tangible chewing gum. It’s a headache for the mining industry, as it’s a vast money pot that we have no access to. It is also believed that Nickel played a part in the Great Dying, the end-Permian extinction, causing 90% of the world’s species to die some 252 million years ago. It created much of human history, if you can put it like that, through its human use in armaments production, and battles were fought to keep or overtake nickel reserves. This metal is a perfect example of how everything is interconnected, in intra-action with each and everything, and in this way, you can say metals like Nickel, have capacities to interfere and disrupt historical moments, and human lives. Everything is intertwined. To borrow Karen Barad: “We” are not outside observers of the world. Nor are we simply located at particular places in the world; rather, we are part of the world in its ongoing intra-activity […] I don’t want the human to be in Nature, as if Nature is a container. Identity is inherently unstable, differentiated, dispersed, and yet strangely coherent.”

I love how she goes on to say that knowing can never be fully claimed as being a fully human practice because we use nonhuman elements when we discover and build on our knowledge, and how do we know in what ways these elements interfere and disrupt, distort this knowledge that we claim to be scientific evidence, for example.

I was looking through some of my grandfather’s books, and I came across this really beautiful quote by Pliny the Elder that was included in The History of Metals, published by MacDonald & Evans. It was originally written for his magnum opus, the Natural History encyclopaedia. In the quote he foresees human greed relating to metals, and he wrote it sometime in AD 79. I felt it was like an omen. The beginning of this quote is included in the book. So, to cut a long story short, perhaps I didn’t really learn anything about my grandfather, but through what he left behind, I discovered a completely unknown world, that had been present all along.

SS: There is a strong metaphor in this work for what constitutes technological progress from ancient times through to the present manifest in the extraction of useful metals for humankind’s advancement. I wanted to ask about how your findings were reconciled in your visual approach and decision making around text and contributions for the book. Are you able to describe how your feelings for these objects and documents become artistic and aesthetic choices?

FH: I’m using the history and the mining of metals as my starting point, as my grandfather was said to be a man dedicated to his work and his profession was metallurgy. In a sort of Marxist way, I thought that if I were to look for who he might have been, I was to look at the work that he did, to really understand it, infiltrate the scene so to speak. The work that he did, influenced his life, but also the life of his children, and I think it also trickled down to us, his grandchildren.

However, as I worked longer on the project, I came to realise that I wanted textual elements to merge with the visual, so that each would support the other by opening portals to different ways of understanding the work. I built the texts as a kind of map or a set of clues, (I have been really impressed and inspired by George Perec’s Life a User’s Manual) that in case the viewer wanted, they could look for different meanings in the images, that went deeper than just the visual. The texts were of course also necessary as the historical context was so specific, that part of Finnish history is riddled with uncomfortable truths that people are maybe only now starting to talk about, as the past generation starts to disappear. I think artists have a responsibility to respond to incidents in their own culture.

In an aesthetic and textual sense, I also wanted to recreate the levels of different times I was working with, and to see them in a way as sort of happening at the same time, that there is no past, no present, or future, just this one, stretching and contracting idea of time. Things can happen simultaneously, or in the wrong order, the past can collapse into the future. I guess I’m interested in the impossibility of trying to build a bridge between the living and the dead, reality and art, history and memory, or memory and oblivion.

And then naturally, I felt it really important to add the factual elements in the writing, to point in a very concrete way to the politics and polemics of mining. Otherwise the book would aestheticize something horrendous, and I was aware that that was a really big issue. I was intrigued by the idea that this beautiful, almost otherworldly rock material containing vital elements, had, in human hands turned into something abhorrent that was necessary for our industrial and material trajectory. However, in saying this, I think it’s also really important to stress the fact that I do not see myself as outside of this process. Here I am, writing this off a MacBook, reaping the benefits of these technological advancements that have made all these products and ways of life possible, for some.

“I came to realise that I wanted textual elements to merge with the visual, so that each would support the other by opening portals to different ways of understanding the work. I built the texts as a kind of map or a set of clues that in case the viewer wanted, they could look for different meanings in the images, that went deeper than just the visual.” – FH

SS: I am very interested in how cultural inflections and histories emerge and coexist in a book presented in English. While I recognise the necessity of a common language and the reach that provides in terms of audience, I like that you’ve stated there is a strong articulation of Finnish culture and history that is re-worked in the present by you as someone who in this case, is positioned across cultural boundaries – Finnish and English. The “visual” which can be thought of as general or universal is diverted towards aspects of the culturally specific with the text. It is an important site of articulating your Finnishness. Is this positioning of culture within work made in Finland a strong current amongst artists, or something you are particularly attune to? In speaking between cultures, is this a comfortable place for you or a problematic one?

FH: Yes, I completely agree with you that translating aspects of another culture into a different language is always difficult, and sometimes seems to me, impossible. I would love to read all books in the original language they were written in, it feels one is always missing out when reading a translation, however good it is. It’s still an ongoing project for me, to learn at least Russian, so that I could read Russian literature in the original form.

During my childhood I spent long periods of time living in various places, and with time, Finland did start to feel, in a peculiar way, foreign to me. Maybe it also has to do with the fact that I didn’t attend a Finnish speaking school until I was 16, so my grasp of the language is, in a way, limited. I used to write a lot when I was younger, but always struggled to find my own language when I wrote, a way to truly express my ideas, so I think photography for me opened up a way to tell the same stories and investigate the same themes through mute images rather than words. Writing still plays an important part in my work, and I think the biggest influences come from the novels I read.

I think this moving around also influenced the way in which I see the world, how I create meaning in it. It is also the reason why archives play such an important part in my work, that those few items and things salvaged when moving, in a way, are an archive of the past that you are about to leave behind. Why are some things saved, others lost? The sense of history we gain from visiting archives, is one which derives from a loaded space. Yet it is a fundamental need that we seem to have, to collect and then preserve, in a strict order, as if there only existed a thin sheet between our very existence and our disappearance, and by preserving artefacts and documents, we somehow hope that we are able continue to exist eternally. To have your narrative immortalized in a story is a way of marking your lived existence as a unique being. In our personal archives, we keep a very carefully curated version of our past, which mirrors all the other archives, in its play of inclusion and exclusion.

A bit on a side street here, so going back to your original question, I do think translating distorts, always. However, with this work, I think the aspects of Finnish culture I speak of are historical and point to a specific time that the whole of Europe shares. This act of silencing a darker area of history is shared across cultures, and I think the form it takes is quite similar, which in a way is interesting. Therefore, I did not find it a problem to be using English. To use a language that only 5 million people speak would feel to me like another act of silencing, when the histories and timeframes I talk about are shared by so many.

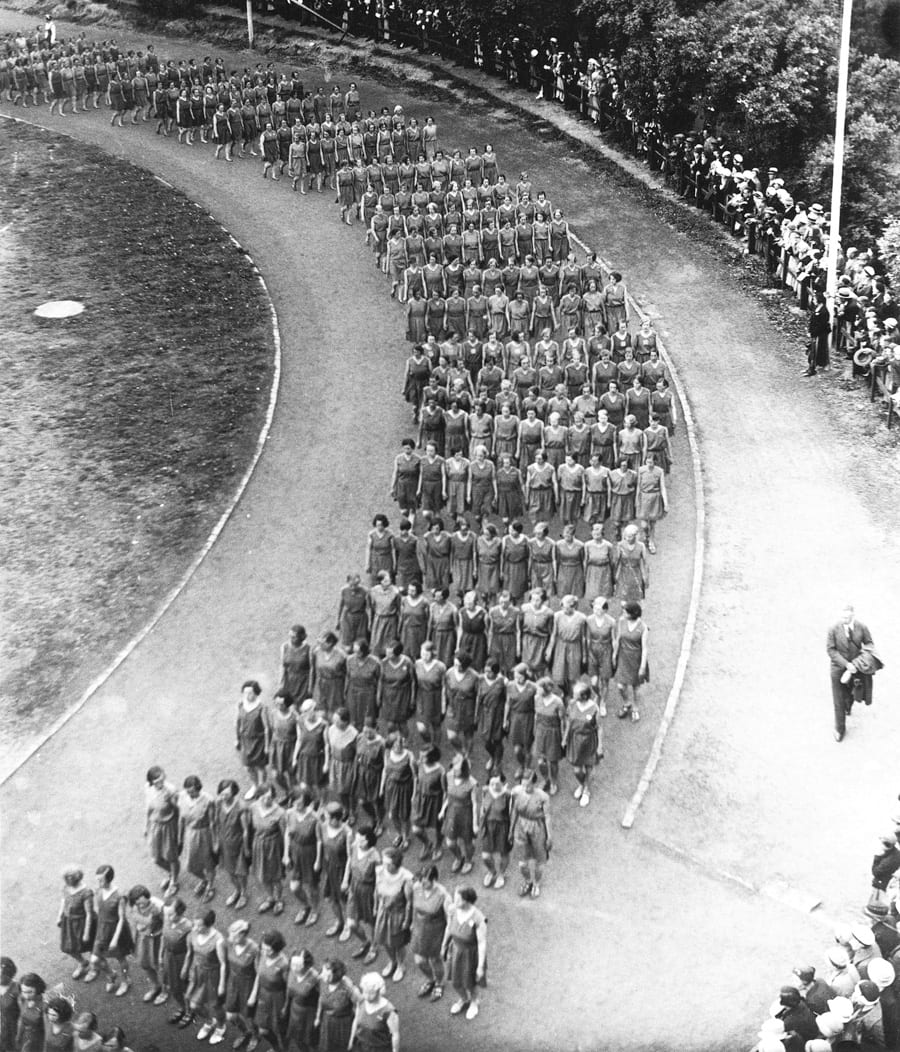

I don’t think you can ever separate the personal from the historical, and I was interested in how bigger historical events influenced personal decisions and also vice versa. For example, my grandparents met during the war in Petsamo, in Northern Finland. They were working at the Nickel factory there. Just before the war, the nickel deposits had been deemed to be the richest in Europe. Germany depended on nickel for their war effort, and the allies tried to stop them from obtaining it. There were political and armed conflicts relating to the access of these ore deposits, and it therefore affected many of the major political decisions of that time. This is an overlooked area in history, that many are not aware of, but I found it intriguing to follow how ore was moving armies across Europe. The area now belongs to Russia.

I tried to visit the place, Petsamo, or Pechengsky District as it’s now known, when I was working on this body of work, but it’s all a military zone. It’s close to the Arctic so no one is really allowed in. The reason they are turning those areas into military zones, is because everyone is waiting for the ice to melt so that they can start drilling the oil reserves, but also the ore deposits, under the ice. That landscape was affecting the whole of Europe during WW2, and some believe during the End-Permian Extinction. The same is happening now, without people really realising it, or maybe caring about it. Some thought we were bringing the world to an end with WW2, and now we are again at a point where the world most likely will end, due to climate change caused by us.

But I also have to point out that this reference to Finnish culture is only one slice of time that the book deals with. In the book you can follow the personal or historical traces, or you can choose a larger timescale by investigating the geological traces, and their timeline. Maybe the last option of three is what I wish people would eventually think about when they have seen the work. Our story, or the story of one culture is only a drop in the sea, whereas I feel we should be talking about the history of those unseen and forgotten histories that have dominated our past and is dominating also our future.

Felicia Honkasalo

Loose Joints

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Sunil Shah & Felicia Honkasalo. Images @ Felicia Honkasalo.)