“The current political narrative that paints immigrants as invaders has been a part of our national conversation for a long time. I want people to be reminded that there is a long and deep history of immigration that forms the basis of our country’s strength.”

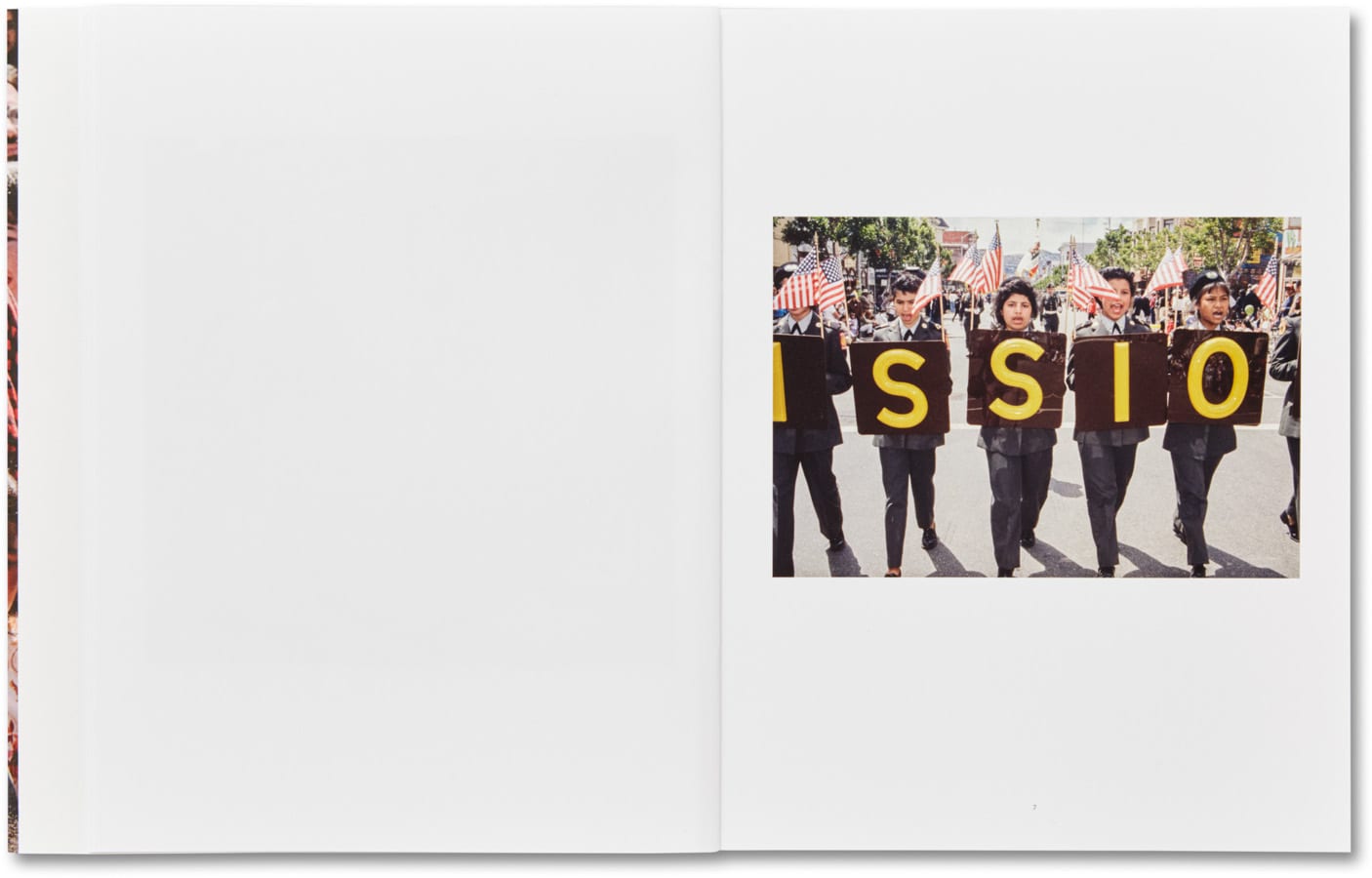

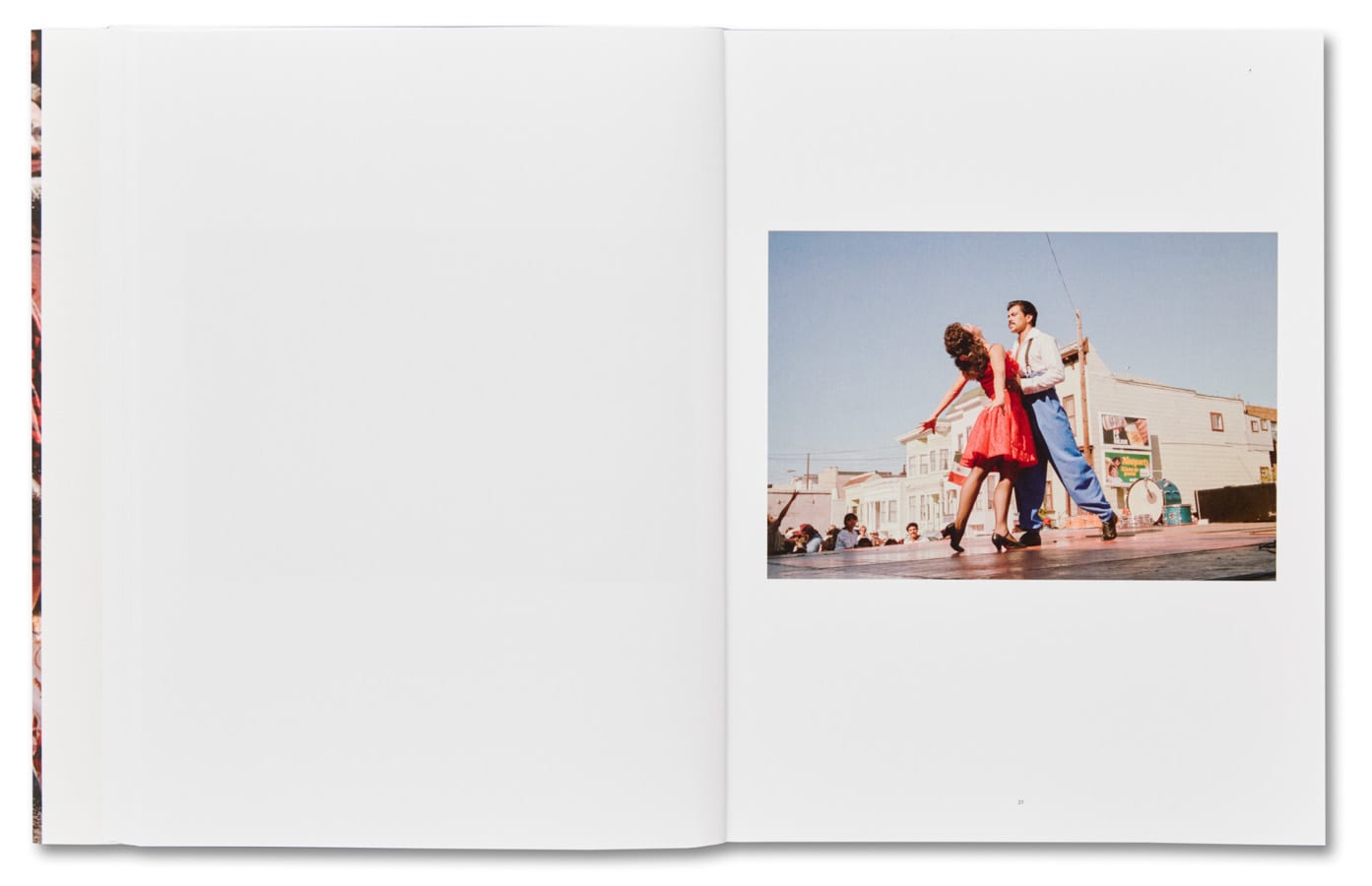

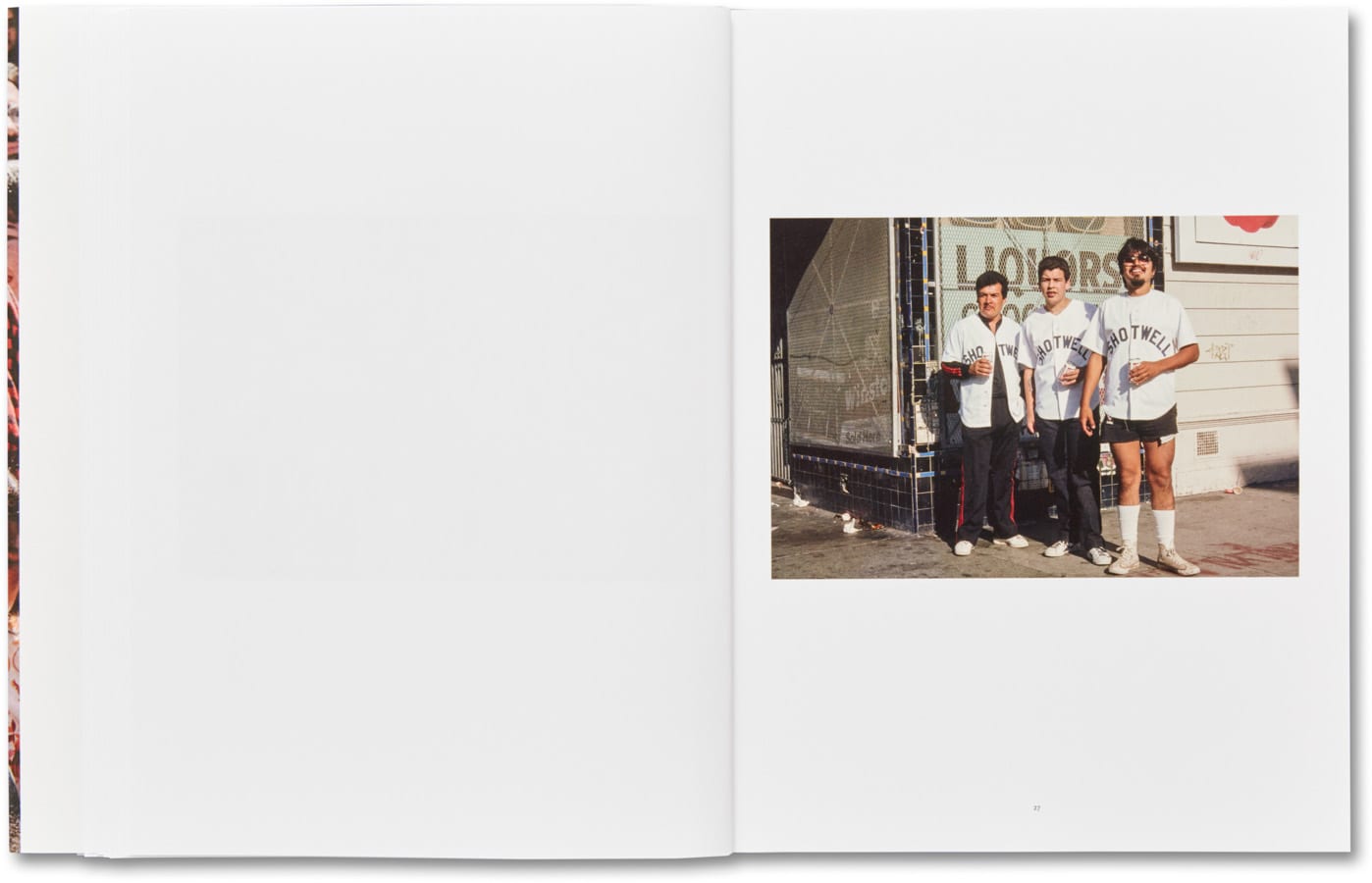

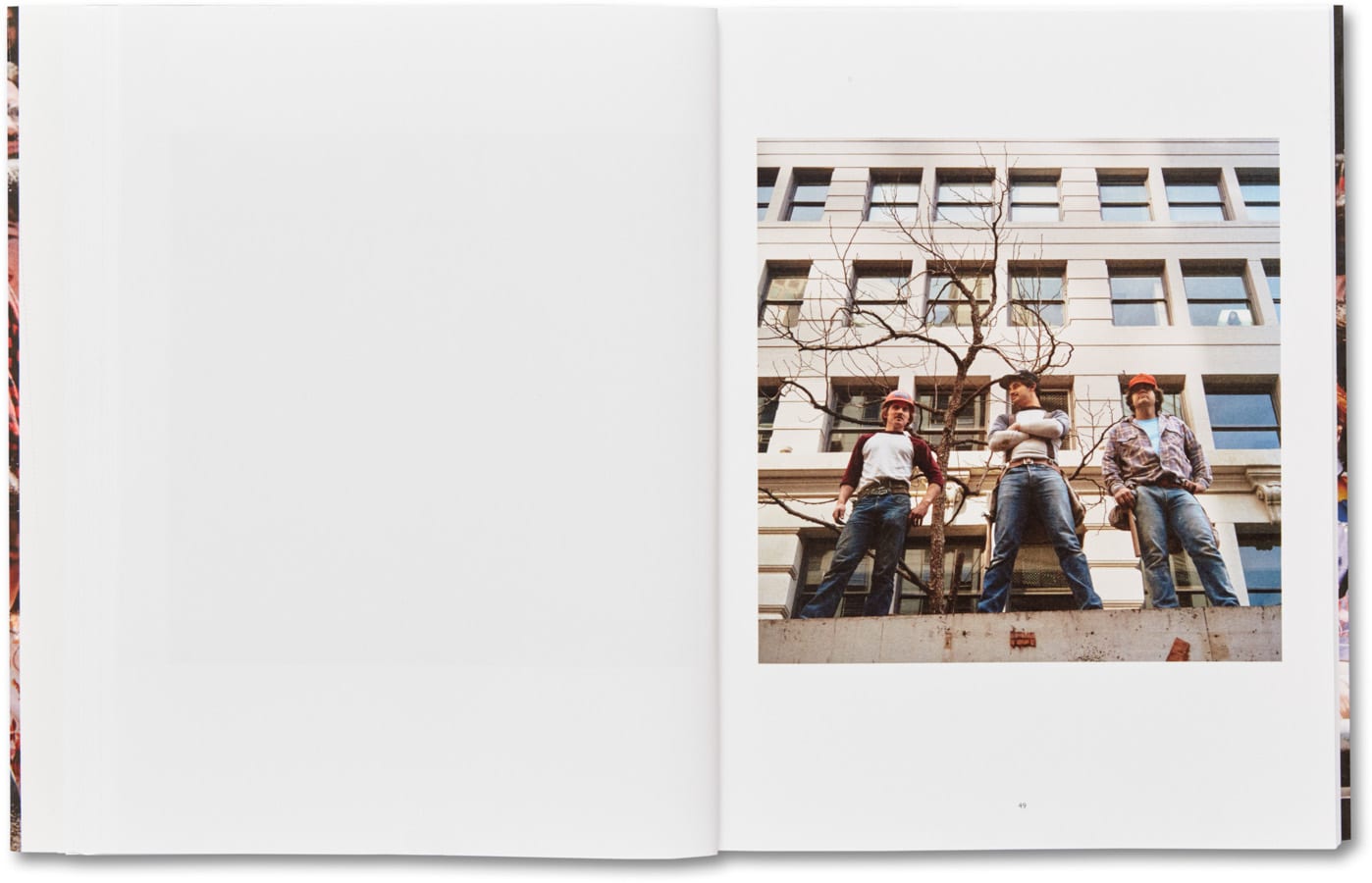

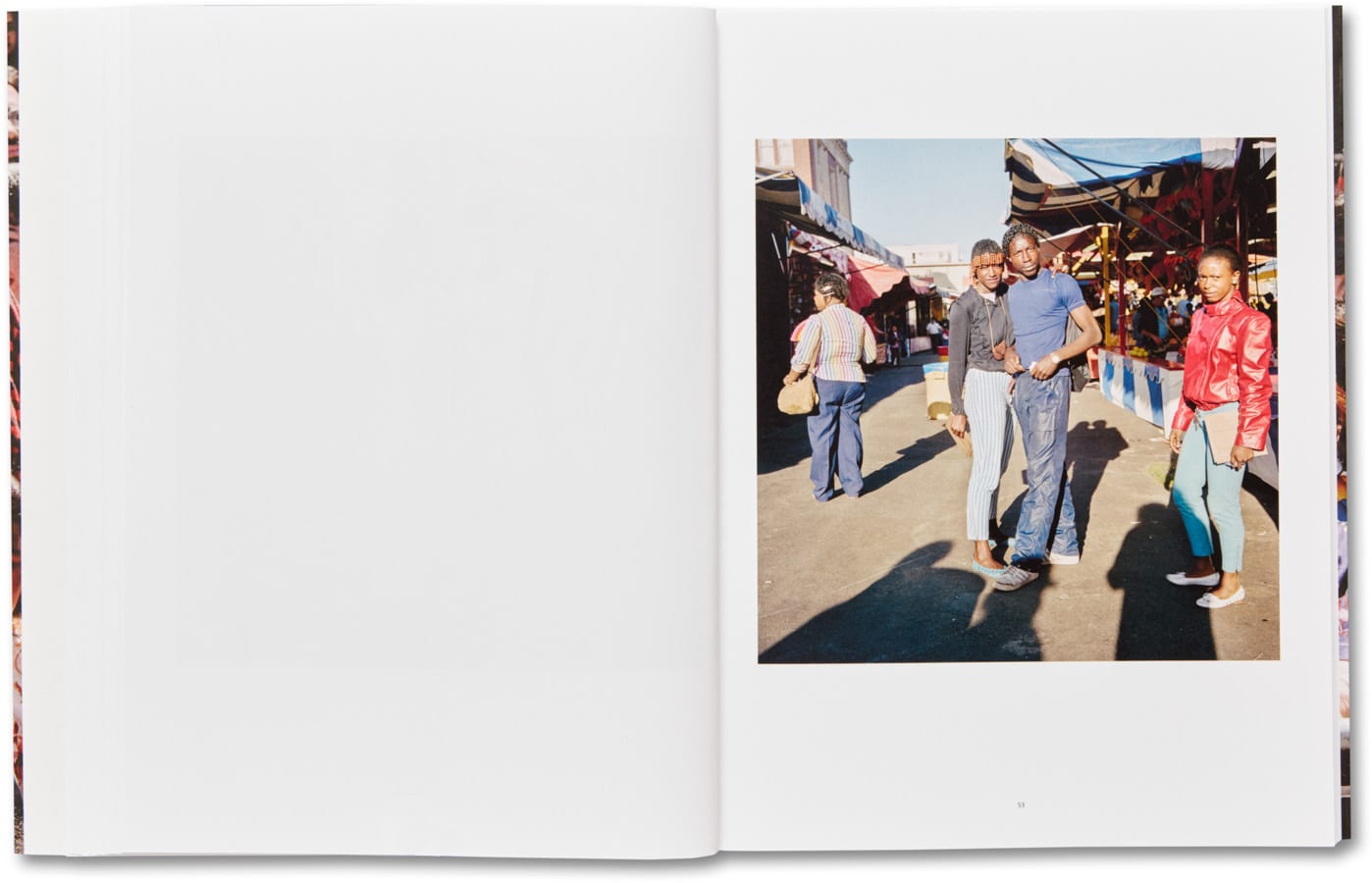

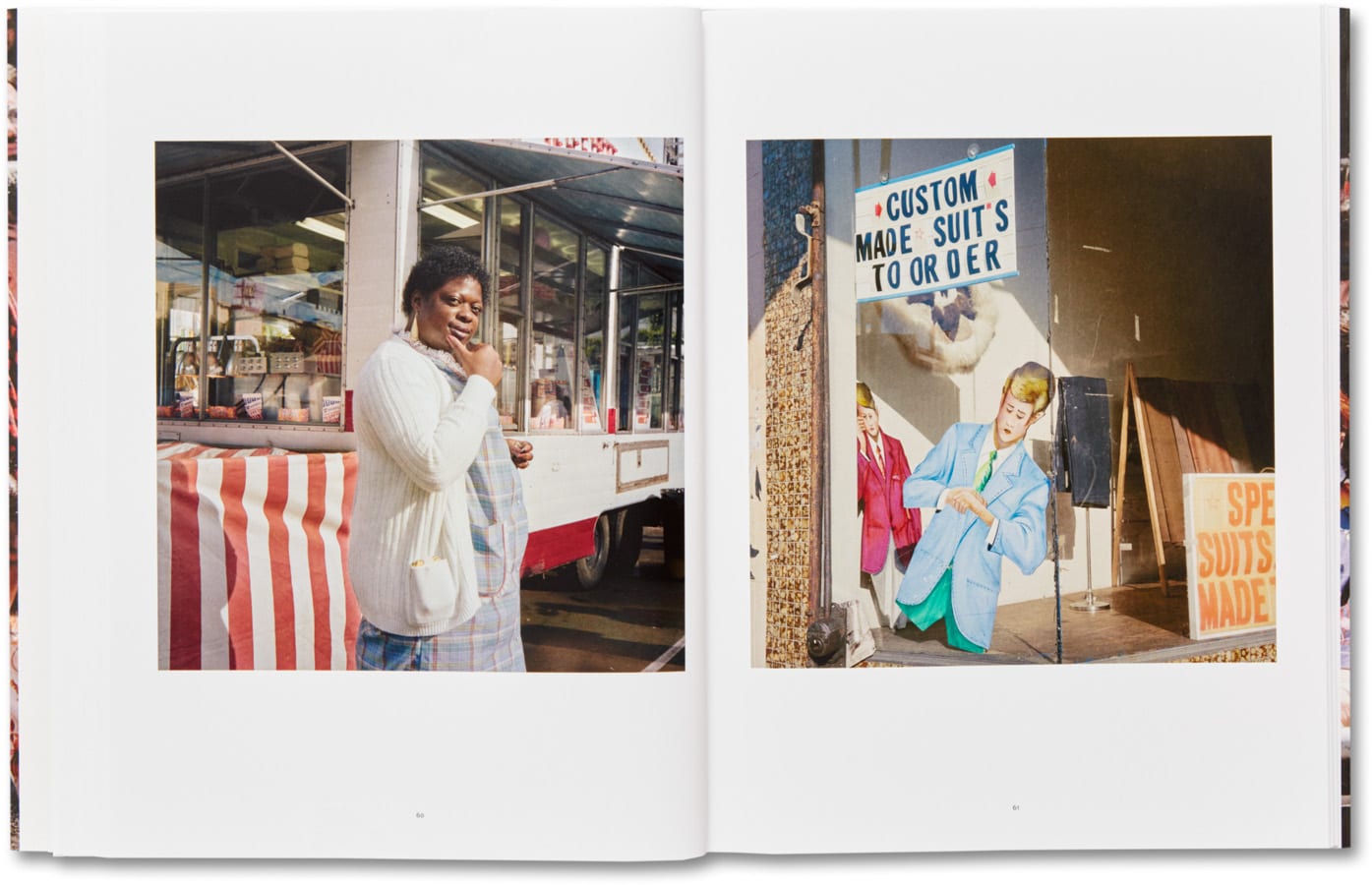

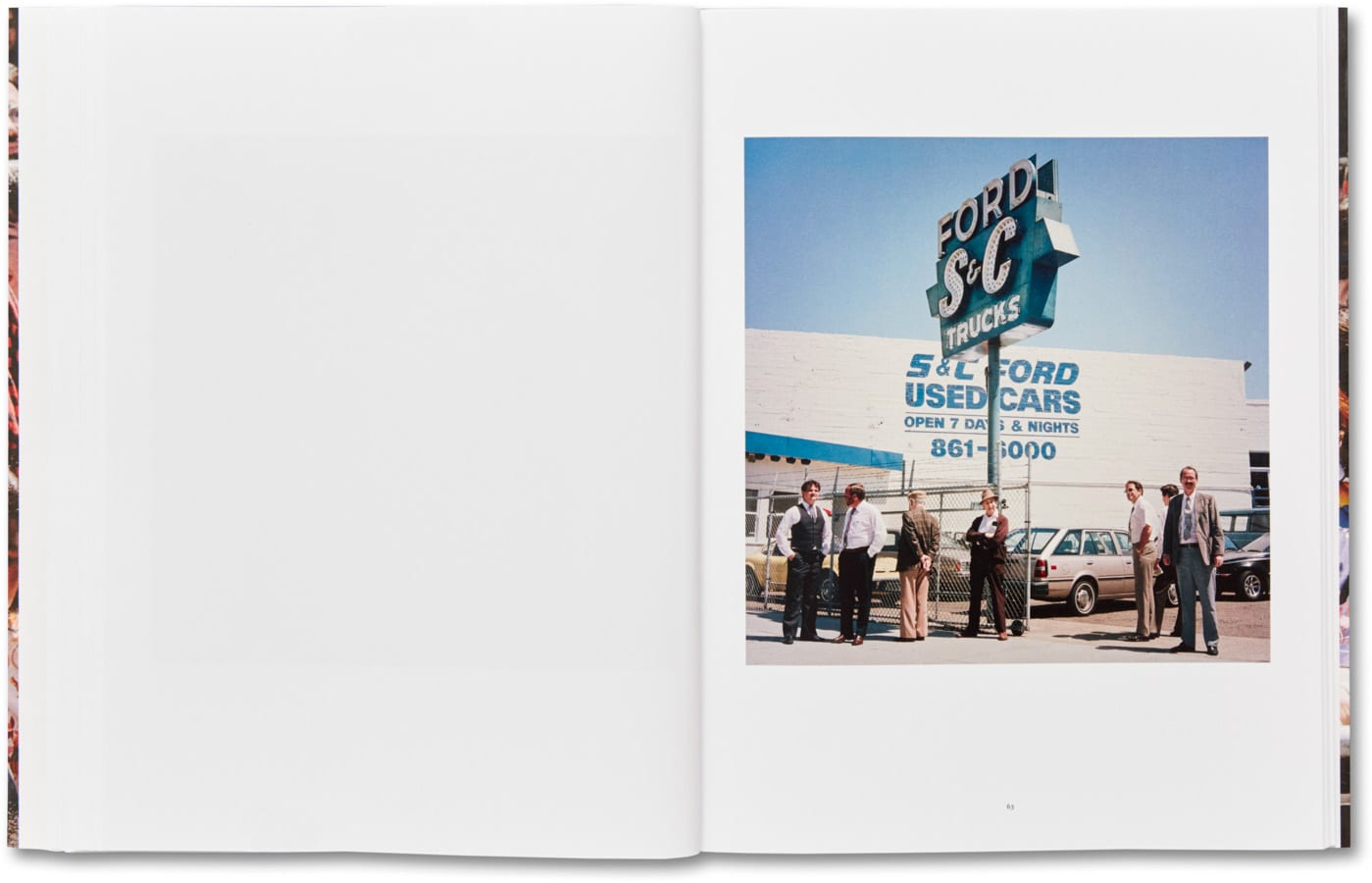

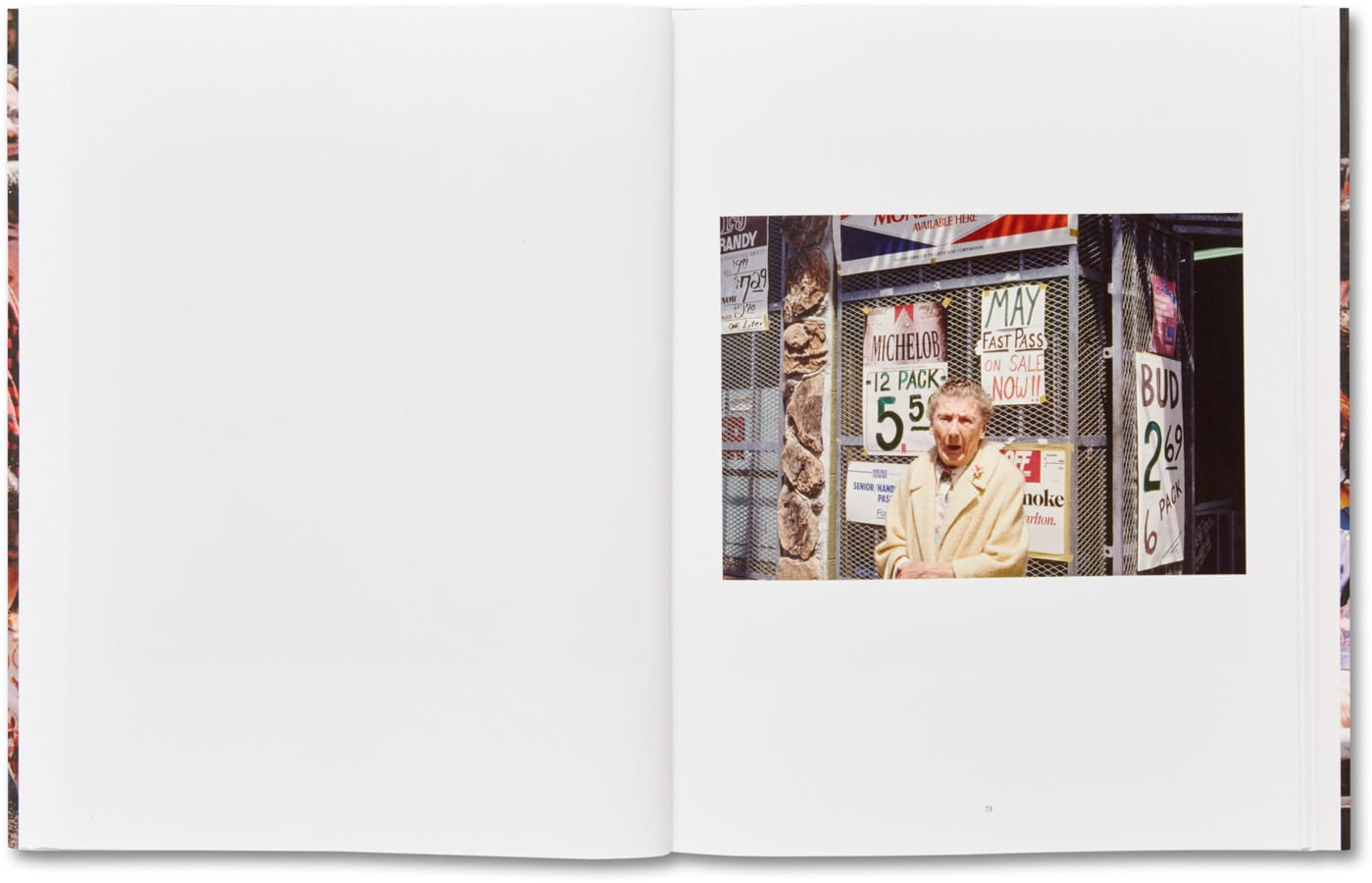

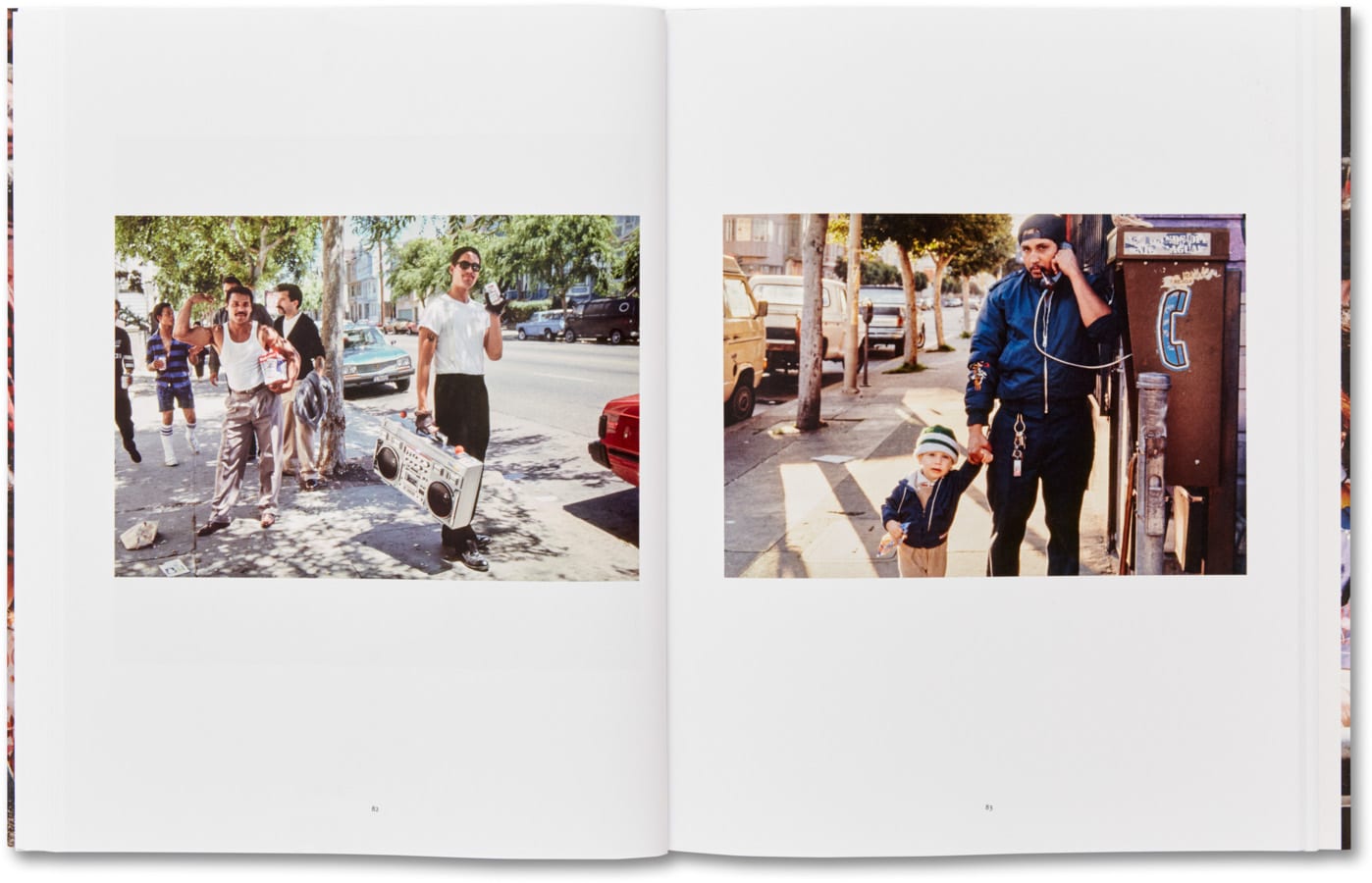

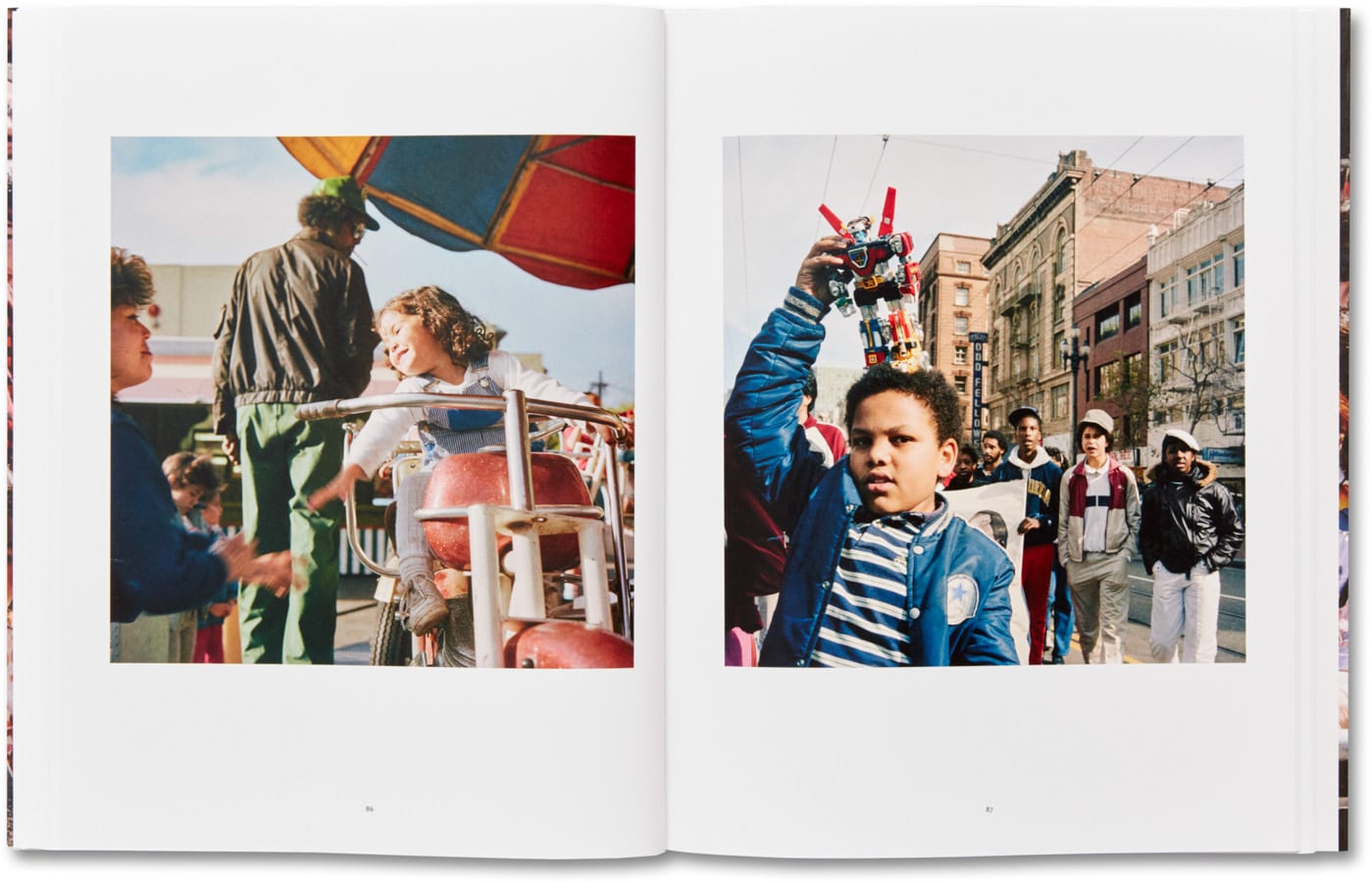

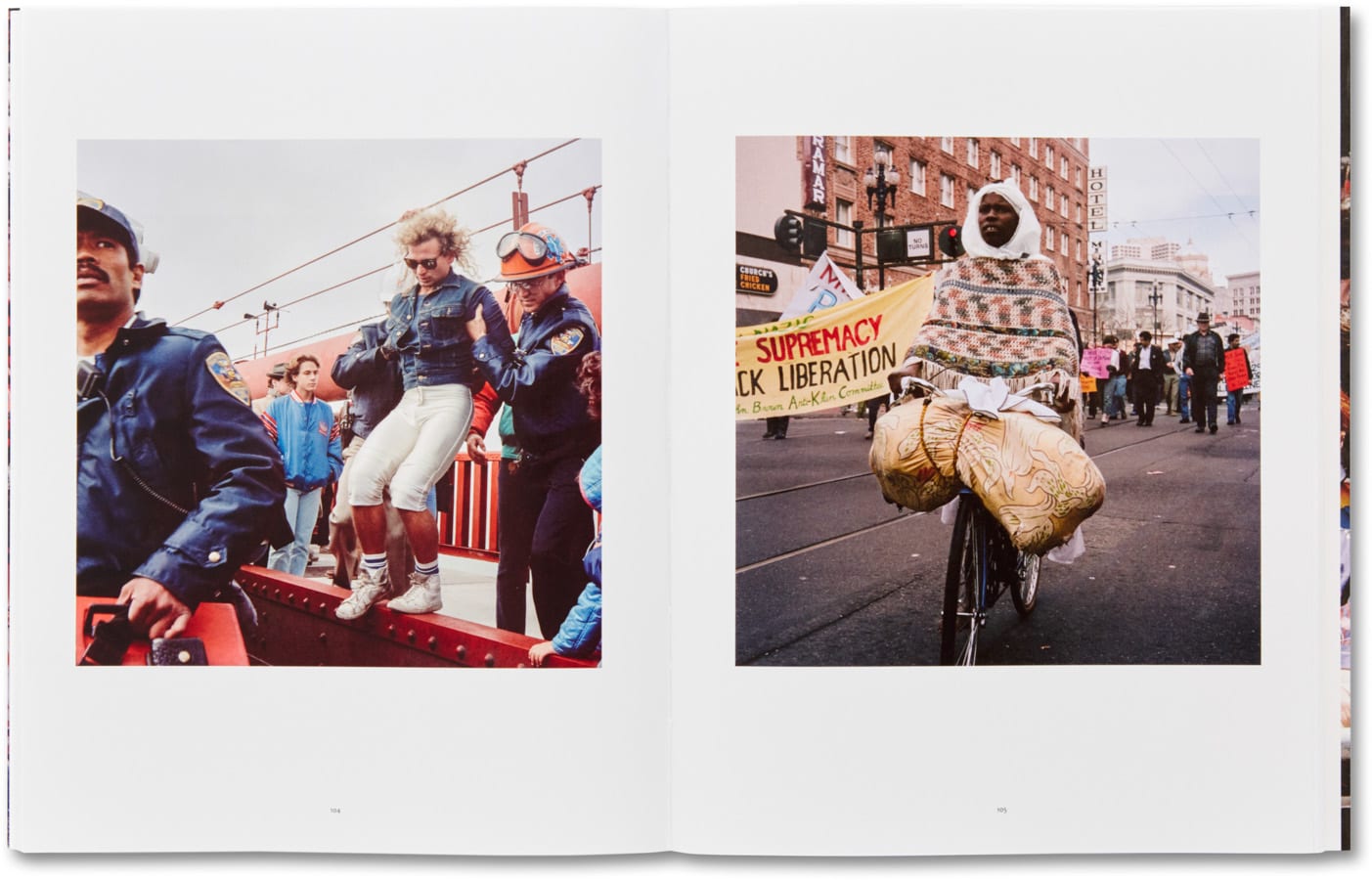

The photographs in Janet Delaney’s latest book on MACK appeal in many ways. Even if we set aside the film aesthetic, colour and detail that takes us back to the 1980’s: hair, fashion, advertising and one or two automobiles – all compelling aspects of looking back in time, we are left with the social and political context in which the pictures were made. This was the Ronald Reagan era when US foreign policy and home affairs took a troubling turn. Much of what was hard fought in the 60’s and 70’s through protest and rights movements was overlooked by Reagan’s conservatism and the people affected by this new administration took to the streets to protest. The Mission District of San Francisco was particularly active and this is where Delaney found herself, not only as a photographer, documenting what she saw, but as an active protestor, a local in amongst the parades, with the people, in the flow of the march.

SS: Janet, can you tell me how and why this collection of images resurfaced after three decades? How did they come to find themselves in this book?

JD: I was archiving slides and negatives from my 1980s South of Market project when I came across these other images I had taken in the Mission District during the same years. I was doing all this during the run up to the 2016 election of Trump. I began to see parallels between the Reagan Era and now.

The current political narrative that paints immigrants as invaders has been a part of our national conversation for a long time. I want people to be reminded that there is a long and deep history of immigration that forms the basis of our country’s strength. And I wanted to highlight the act of public life in both protest and parade. As we become more isolated by technology it is important to celebrate our common presence and encourage civic engagement.

In January of 2016 I showed Michael Mack a box of prints that was a very rough edit of my idea. Based on a short conversation I spent about a year and a half editing and sequencing the work so that I could make my case.

SS: The outwardness of public life is the antithesis of the insular, virtual worlds we are building around ourselves through technology containing only the narratives we care to want to know about or believe. Yet, I am encouraged by recent protests and shows of solidarity that we have seen in mass protests in this Trump/Brexit age. I draw this US/UK parallel together as I think they are being driven by similar ideology. Public life is how we come face to face with each other, it’s not necessarily always harmonious but it is a vital theatre in which politics can be played out, reinforced or contested. What were the intercultural relationships in the area these photographs were taken and was solidarity effectively forged?

JD: Intercultural relationships were everywhere. There was an outpouring of support for those in Central America fighting to free themselves from dictators and from US interventions. This support came from church members, from construction workers and from young and old supporters of the Sandinista movement who went to Nicaragua to volunteer in the coffee harvest, the literacy campaign or to offer tech support. Native English speakers took classes in Spanish to prepare themselves to be advocates for those who were arrested, to monitor voting in Central American elections and to offer medical aide to those living in conflict zones. The people of San Francisco and in particular those living in the Mission District were incredibly active in response to the wars that created the immigration crisis of that time.

There were those who were fighting for gay rights as well as civil rights. My photograph of the man in a girl scout uniform carrying a sign that says, “Cookies Not Contras” is but one example. Another photo shows parallels being made between the AIDS quarantine and South African apartheid. The response by the community to the AIDS crisis was to set up food banks such as Project Open Hand which now serves people with health issues across the spectrum.

Was solidarity effectively forged? I can say at the time it certainly seemed as though we were working together to address a broad range of issues from international conflicts to environmental crisis to the AIDS epidemic. Many of the organizations that were established during this time are still going. Many of the activists of the time now hold public office in San Francisco.

“There were those who were fighting for gay rights as well as civil rights. My photograph of the man in a girl scout uniform carrying a sign that says, “Cookies Not Contras” is but one example. Another photo shows parallels being made between the AIDS quarantine and South African apartheid.”

SS: Many images in the book indeed reflect a sense of great pride and solidarity. Can you tell me how your photographic style developed during this time and how it adjusted between the urban landscape images and for this particular project, which focuses on people on the streets? Of course, there are similarities and crossovers with the South of Market work. What did you look for in making an image successful for you in both cases?

JD: I have always tied the sort of equipment I photograph with and the kind of presentation that I make to the larger idea of what I want the work to say.

For the South of Market project, I had been working almost exclusively with the 4×5 view camera. I felt that the big expanse of broad boulevards and brick warehouses that made up this light industrial neighborhood needed to have color and the larger format camera to do them justice. I also found that this formal format created a reverential view of the people who lived and worked there. I wanted the photographs and text to draw attention to a very working-class neighborhood that had been so overlooked that the center of it could be bulldozed for the construction of a convention center.

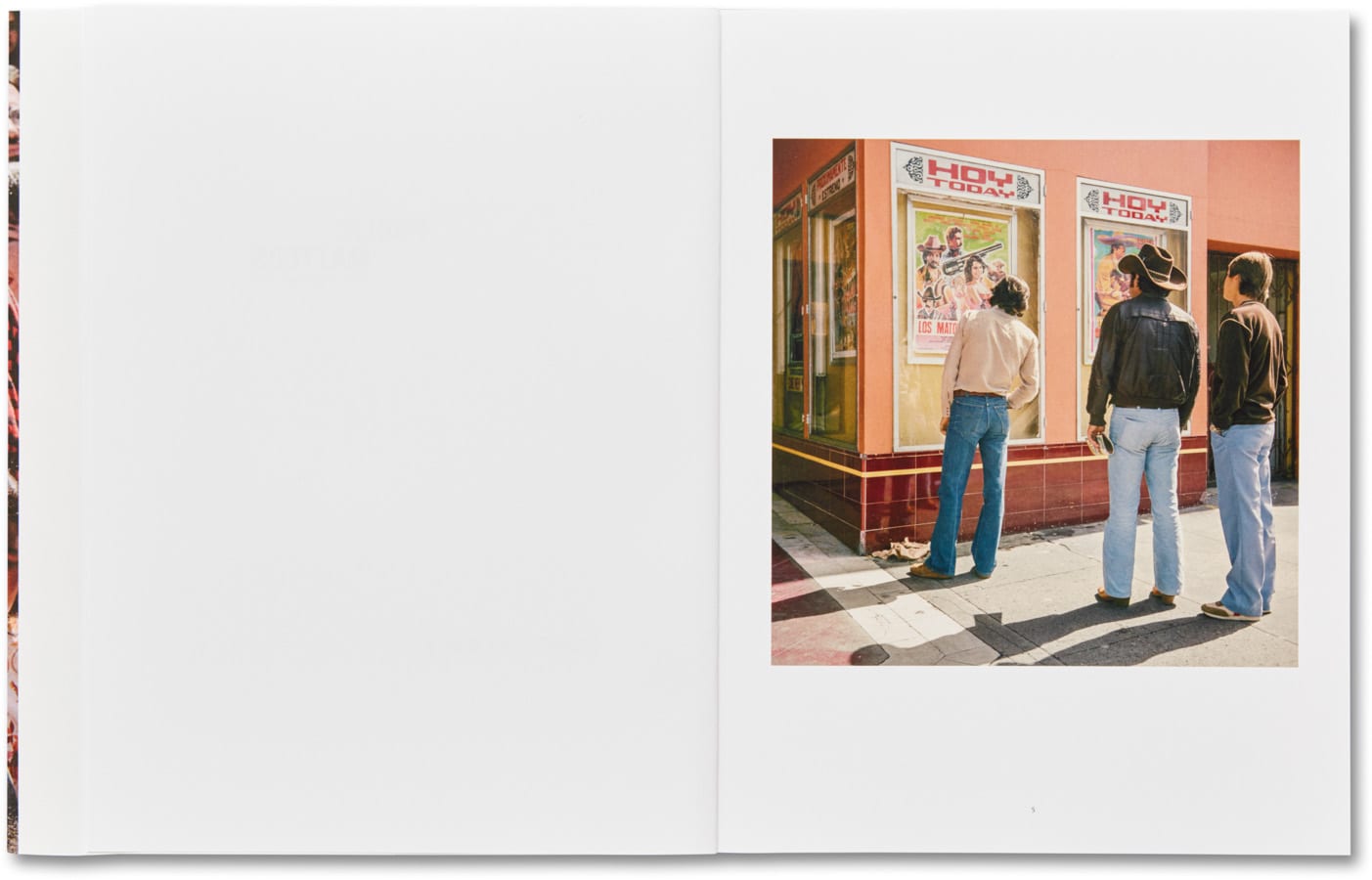

When I arrived in the Mission District I was ready to have a freer, easier approach now that there were so many people on the street. It was a very lively neighborhood. The 35mm camera and the twin lens reflex were the right tools to capture the sense of place that was more centered on the people than the architecture.

SS: It is interesting how camera technology leads towards certain approaches: the large format a slower, considered process that captures details, the handheld formats allowing fast, responsive and relatively unintrusive ways of working. At the time you made this work, was it your intention to make work for an art context or was it as a documentarian? I know for many photographers there is no distinction and for some there is.

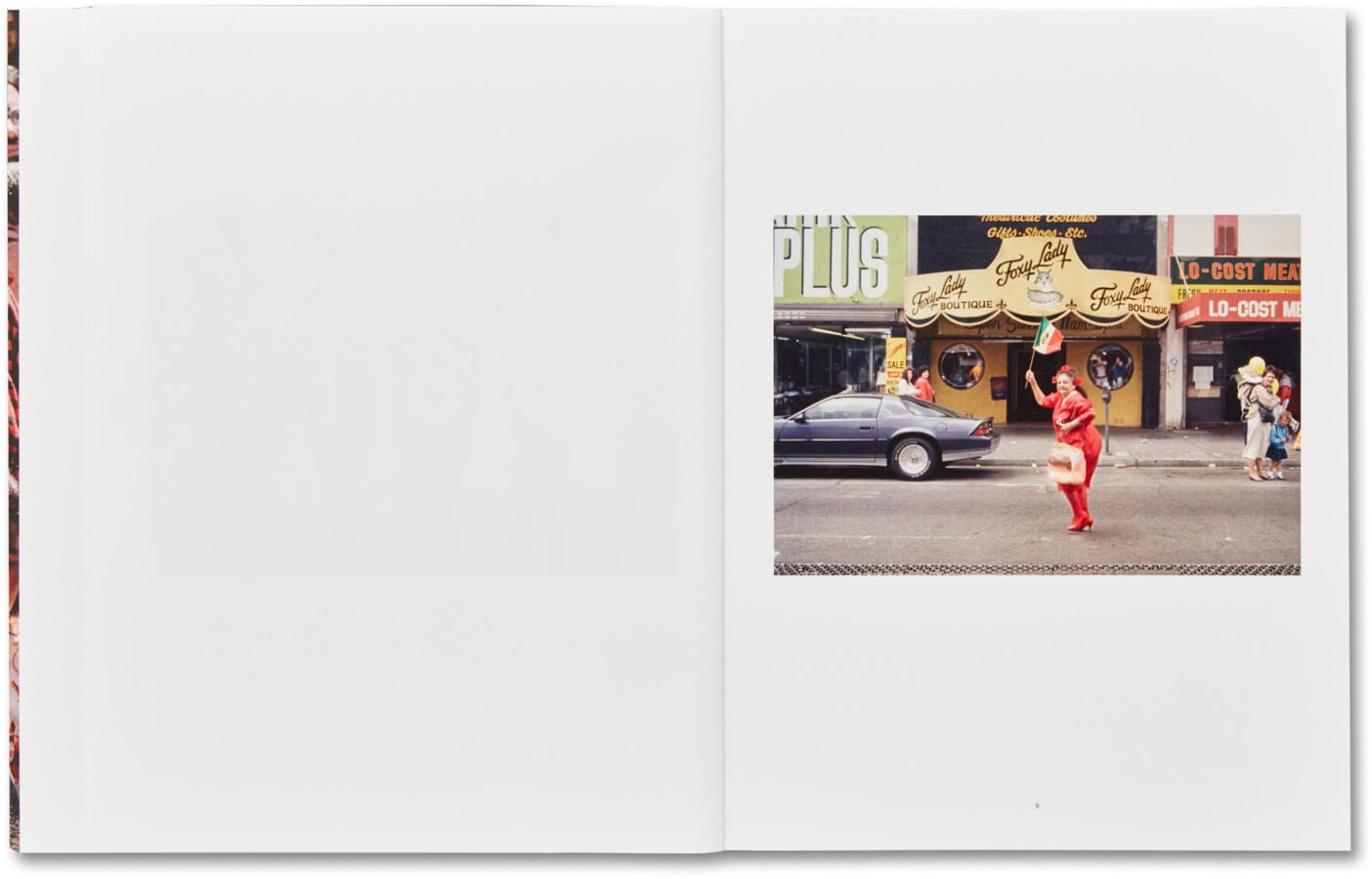

JD: I have never worked as a strict documentarian with the journalist framework of objectivity. In the Mission, the farmers’ market and various protests and parades I was making photographs for the sheer pleasure of photographing. I did not have a firm agenda. I thought of them as family snapshots of our shared urban experience. With time their meaning and use has evolved as has the way we view art and photography in particular.

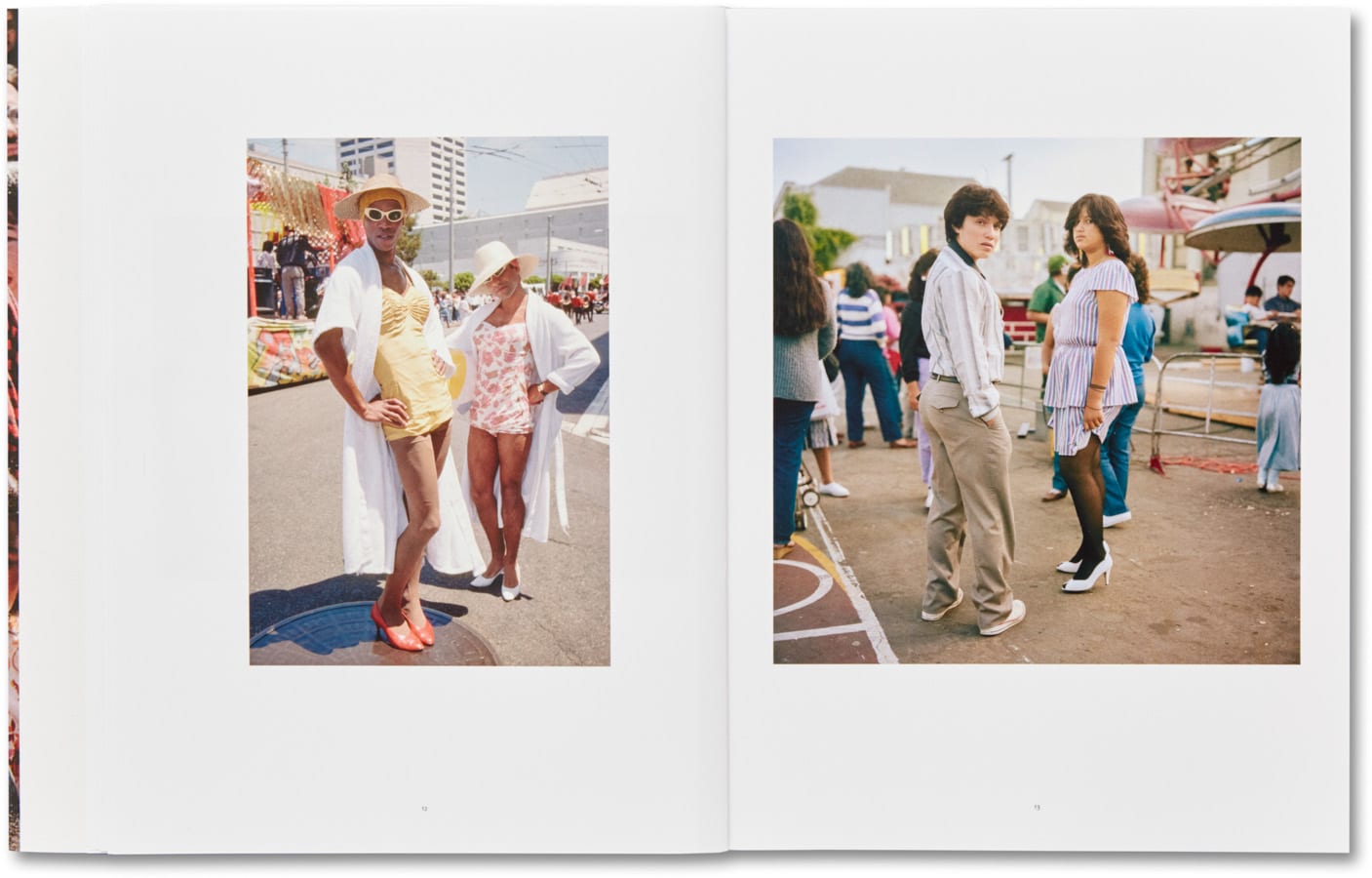

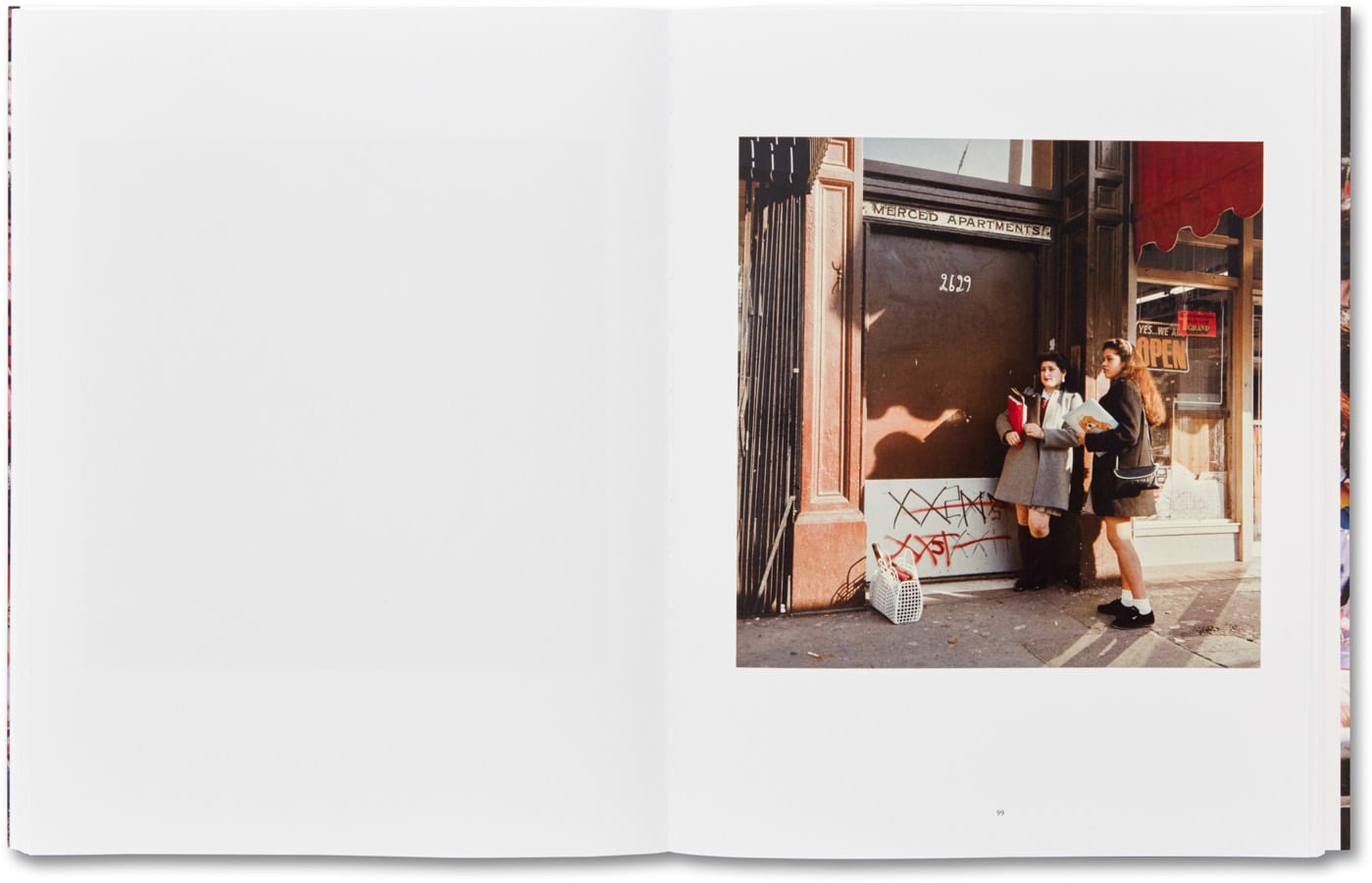

SS: I like the idea that for you this experience was not just as an observer but as an active participant in the parades and protests, for issues you cared about. I think that shows in the images as does your personal subjectivity. It can be seen in the people you capture and the details and gestures that become foregrounded. Although I haven’t counted the images of women, I feel there is a slight gendered weighting to the book which I really like. I think gives the book a personal connection through the soul of its creator. Is this something that has been brought to your attention before and do you have any thoughts about your choices in photographing and editing?

“Not only did I care about the causes, I also loved swimming with the crowd, camera in hand, being swept up in the sound and heat of the moment.”

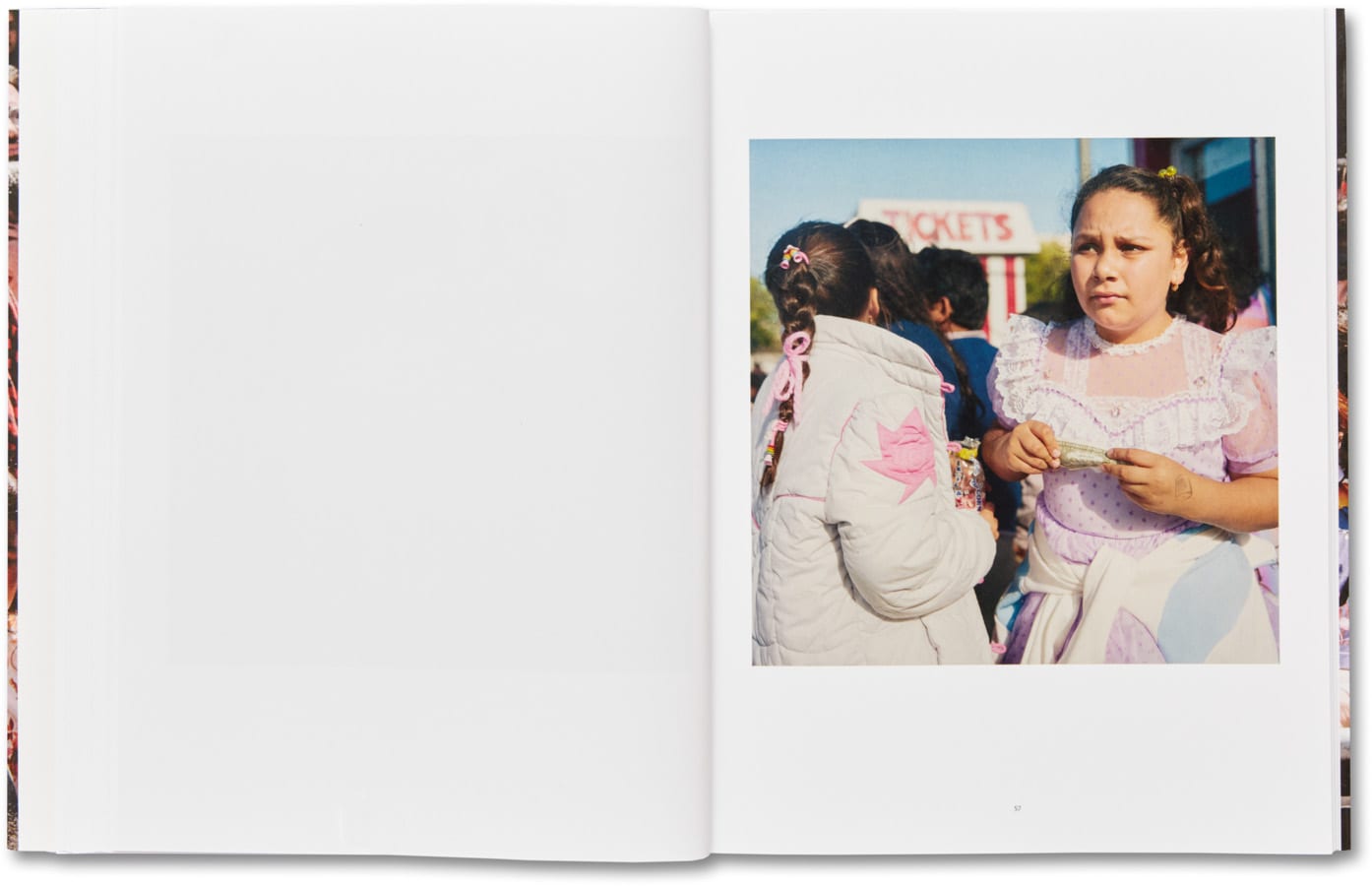

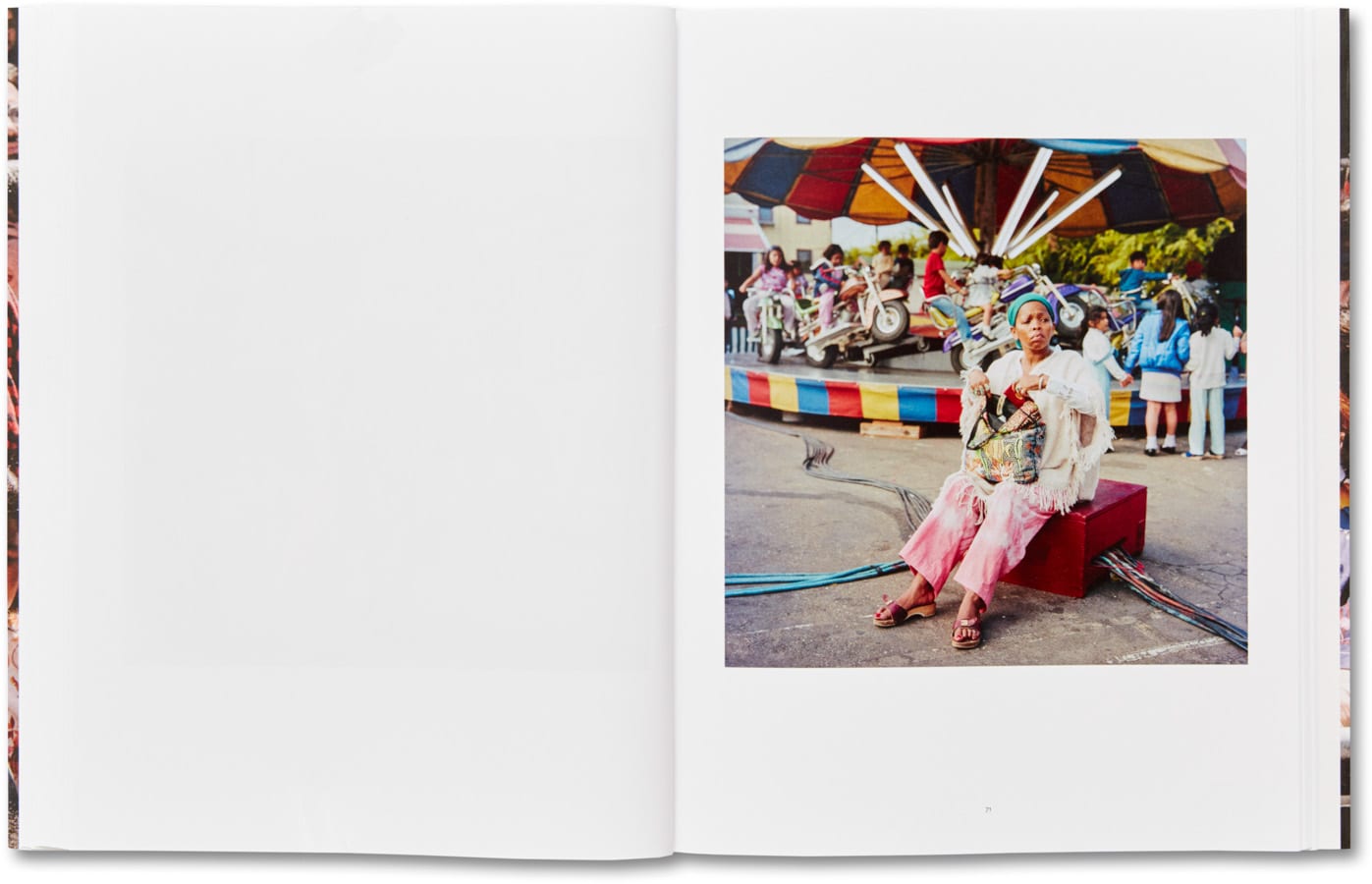

JD: Yes, I was really involved in these protests, not just photographing on assignment. In fact the photographs, if used at all, were seen in political journals such as the Nicaraguan Perspective or the Livermore Action News which lobbied against nuclear weapons. I photographed for the Peace Navy, the Construction Brigade to Nicaragua, the Anti-Nuclear Action Network to name a few. I photographed for Oxfam’s Tools for Peace tour in Central America. And I photographed all the protests and parades in my town. Not only did I care about the causes, I also loved swimming with the crowd, camera in hand, being swept up in the sound and heat of the moment. And when there were no actions to document I would wander over to the children’s carnival or down 24th Street or Mission Boulevard to make photographs of people living life in public places.

I too noted that there was an abundance of images of women, both young and old. And many with children in tow. I don’t think this was intentional, but in hindsight I think I was in a great deal of flux about my own life so I was looking intently at how others were living their lives. I was in my early 30s, newly single and ready to have children, which is not an easy place to be. I reviewed the book and saw that about 50 of the 80 photographs feature women as the main characters. Sometimes I think that the camera can be like a divining rod, showing me what I am thinking about. And the editing process I was again drawn to the images of women at all stages of life. But I would never want to just feature women as that is not the world I live in. The conversation between images of men and women is what I find most compelling.

SS: Thank you for sharing this personal perspective. Despite the social and political nature of these photographs, knowing this provides a deeply subjective and autobiographical layer to the project, which makes me like it even more. Finally, I just wanted to ask you your thoughts about what this book means to you in the present time. I know you have been photographing in the city again, what has changed in terms of the city, it’s architecture, it’s people and their concerns?

JD: Putting together the 1980s photographs for Public Matters highlights what is and is not present in San Francisco today.

In both Public Matters as well as South of Market, there is a strong sense of racial, economic and cultural diversity. Statistics and experience show that this diversity is definitely waning.

The skyline of San Francisco has undergone a radical transformation. New high-rises built primarily in SoMa have been coming up nonstop since, 2011, the end of the Great Recession. These new buildings house Facebook, LinkedIn, and other large tech companies as well as high end apartments and condos. These glass boxes could be situated anywhere. The unique quality that is San Francisco won’t be found in most of the architecture of this area. There is a fight to keep low to moderate housing in the mix, but it is impossible to keep up with demand; one unit of new housing is built for every 7 new jobs. San Francisco’s cost of housing is the highest in the country. There are still working class and middle-class people, but it would be very difficult to arrive here now and find an affordable home. So, the trend is toward a city that works well for the wealthy and a city that must struggle with the indigent who sleep on the streets. Housing and homelessness are the paramount issues for San Francisco.

Still, there is a strong civic spirit that is working hard to keep the unique character of San Francisco alive. The Mission District has formed a cultural district, the Philippine community in SoMa is organizing to maintain their cultural presence. Keeping cultural organizations alive is essential to the health of the city.

Public Matters

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Sunil Shah. Images @ Janet Delaney.)