“On one hand, the experience exists totally outside of language. I am not surprised that we struggle to describe it, and relegate it to some other, private realm.”

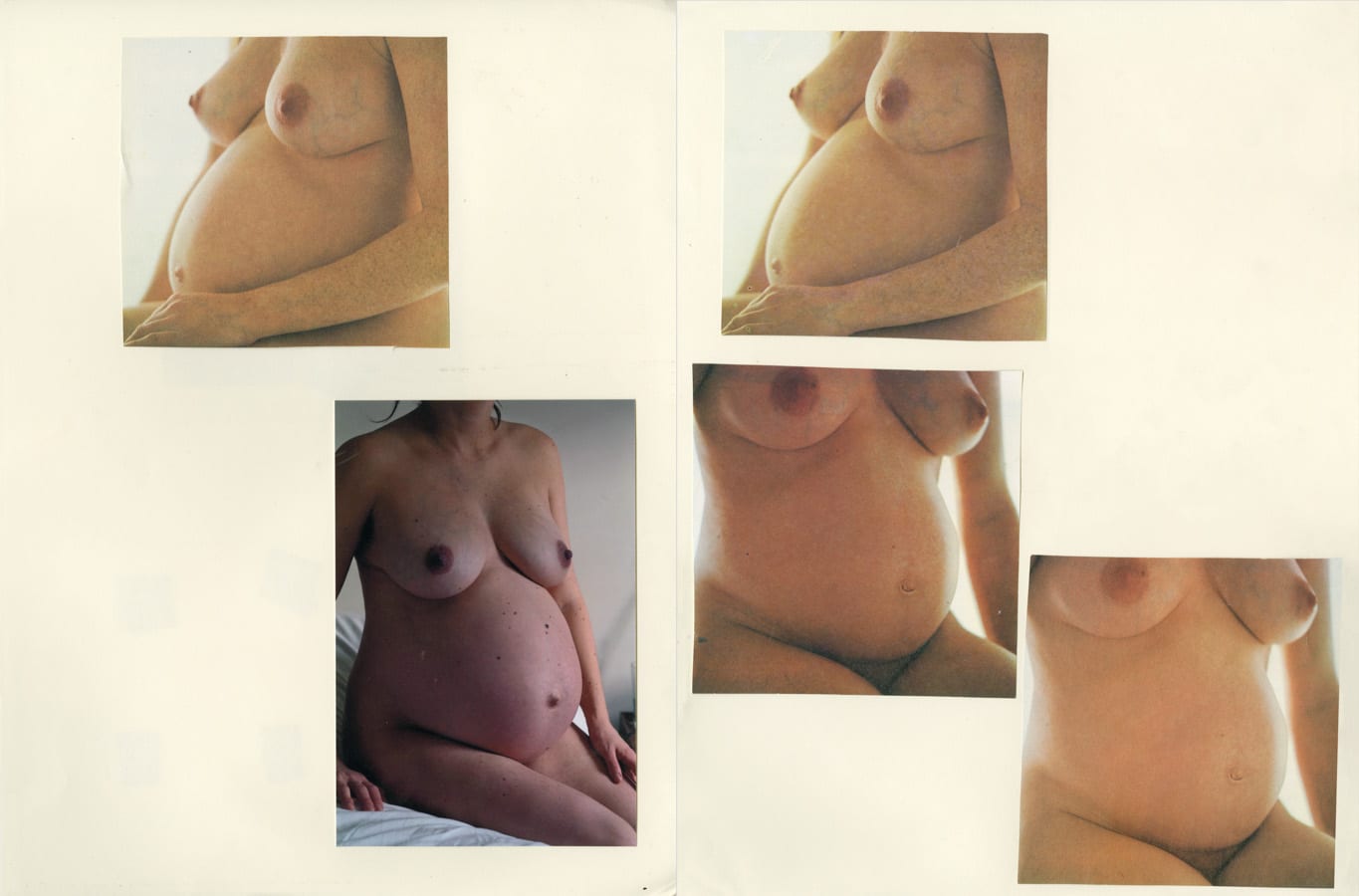

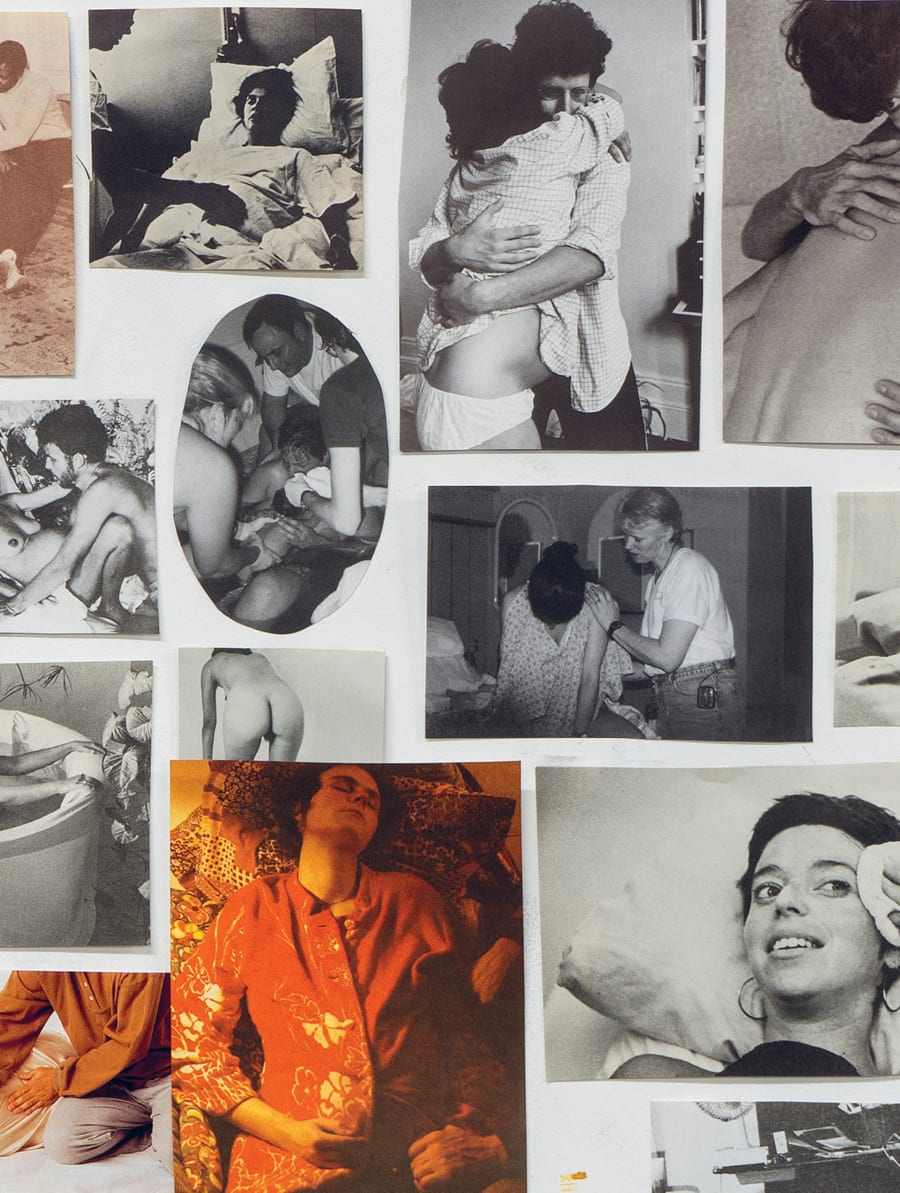

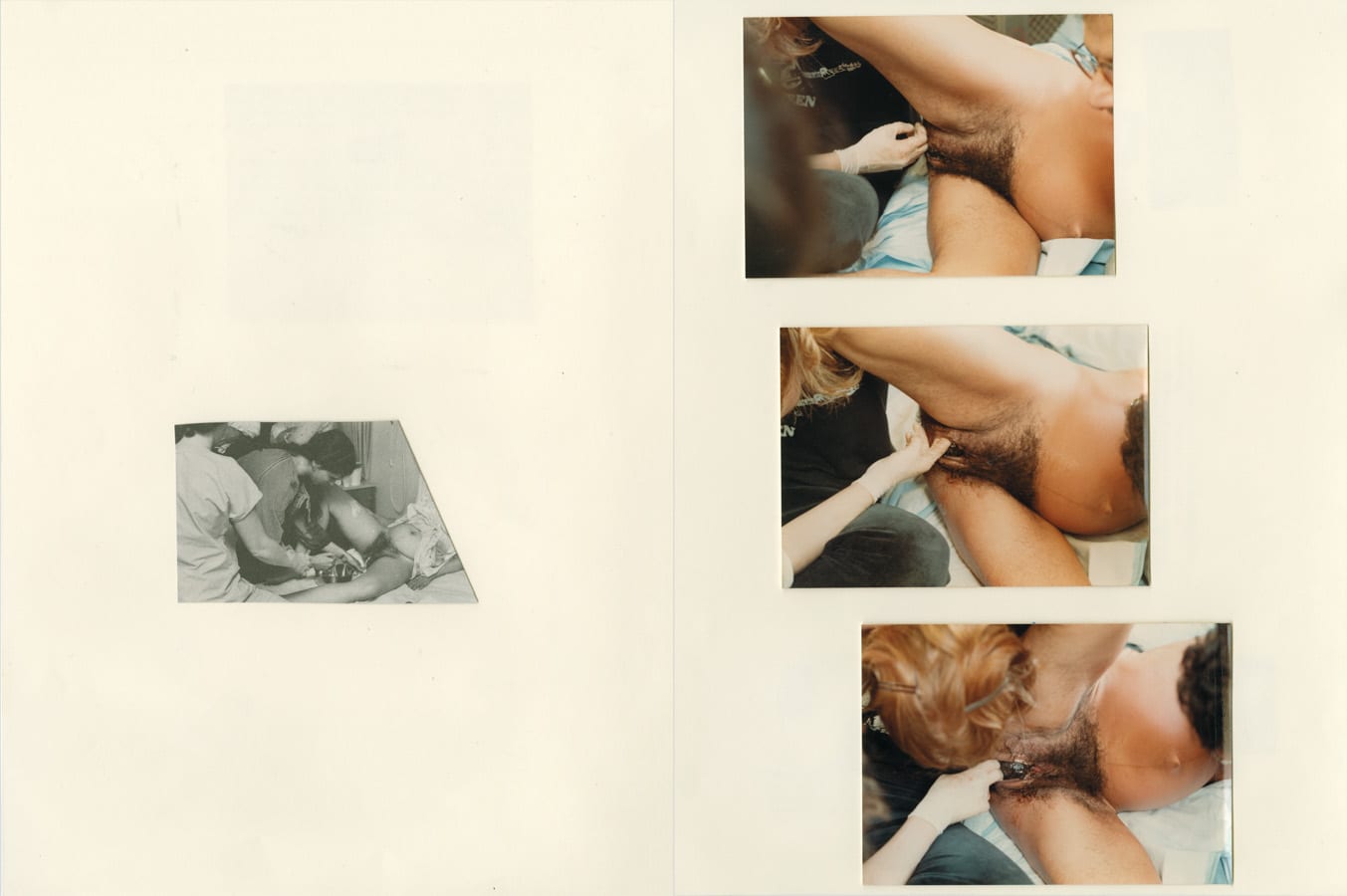

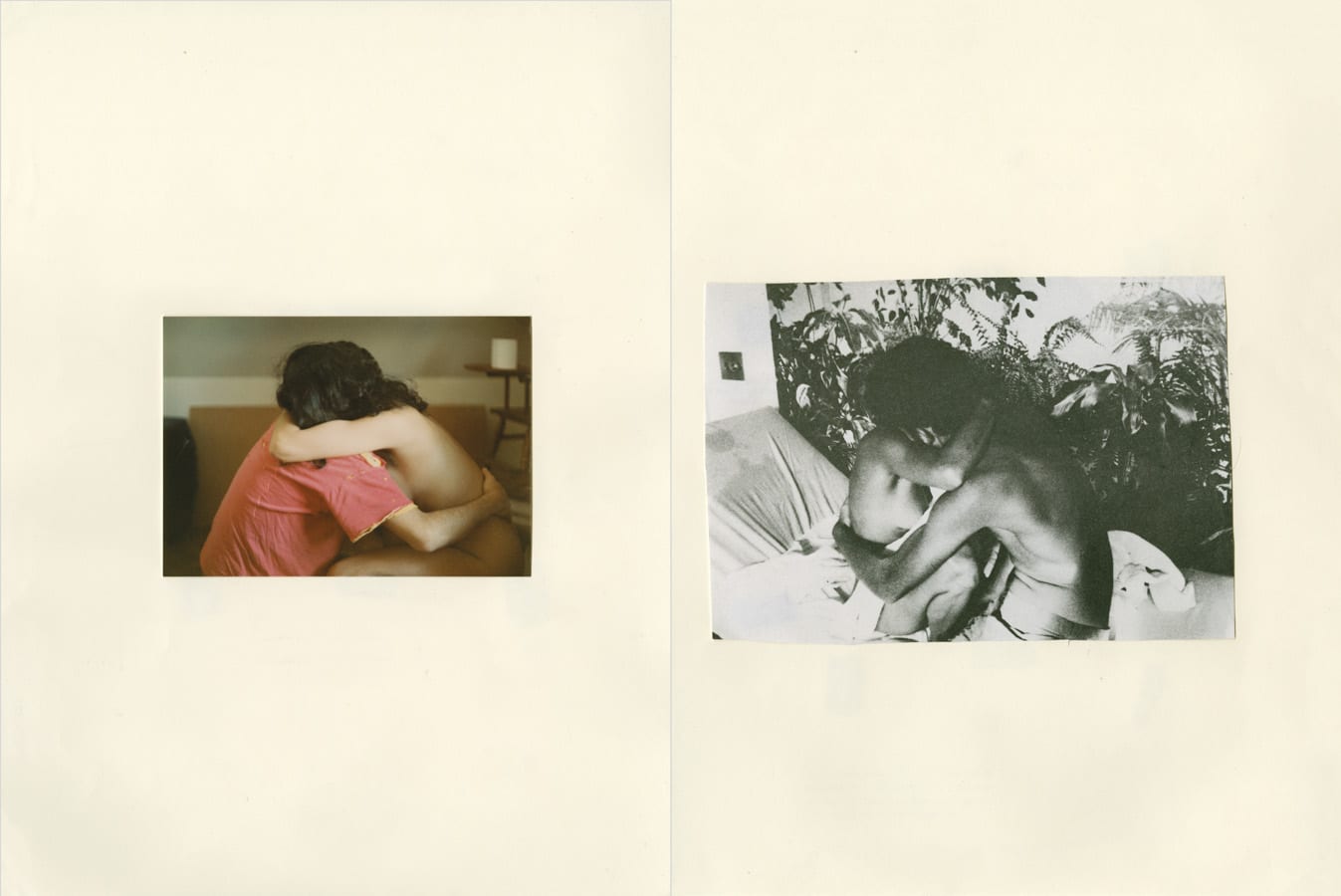

Few natural acts of human endeavor are left so voiceless as the experience of birth. We photograph what we ingest, we photograph weddings, we photograph first birthdays, and yet the birth of a human child is something that eludes our ability to categorize into a language of universal possibility of image. This is not due to its universal nature, but perhaps due to the sheer and overwhelming megalithic architecture of the ritual and action. It is also to be complicit in some small way with our own death in the midst of the most punctuating moment of life. From this point of maturity, we give over to another life form; we sculpt our experiences with the needs of others and our intimacy bears new weight that is more complex as we meander through the abraded stream of life. Carmen Winant’s “My Birth” is an incredible and timely investigation into the ritual of childbirth through the use of predominantly found images and text. The volume of images that she has sourced have come from personal archives of her family and also the books and various ephemera relating to child birthing over the past 30-40 years in particular. The use of this volume is astute, clarifying and brave. I am grateful that she had time to answer my questions about the work and life in general.

BF: I have always tried to hold out on becoming a father. I can’t exactly place why I never wanted kids. I remember being 14 and just sort of opted out along with religion. Perhaps it was the single parent, single child status (Friday’s Child to the denizens of La Crosse, WI). Perhaps I found Bukowski and Nietzsche in my early teens for better or worse. I grew up Catholic and have a long history with my perception of the body. Having a single parent mother, I was also calculably introduced to the mechanics of womanhood by proximity. I never felt disgust about the bodily process a woman goes through in life, but pregnancy certainly had an air about it that I could not completely fathom. Though this is a bit of a disclaimer, I find huge resonance with your project “My Birth” having become a father in the past 14 months. I find it so strange that we don’t outwardly speak on the topic more. It’s a very intimate personal affair and that I can understand, but its almost been cautioned or hushed in society. As a first question, I just want to ask, what are your thoughts on why we “closet” the ritual of birth to such an order?

CW: I ask early in the book: is birth too big for words? Or is patriarchy overwhelming birth? The answer to this question, a version of your own, is probably both. On one hand, the experience exists totally outside of language. I am not surprised that we struggle to describe it, and relegate it to some other, private realm. How to put words to the fact that certain bodies push other bodies out of them? On the other hand, because we treat women’s heath and reproduction as a less serious social and political category, birth isn’t often treated as the profound, moving, and momentous experience that it so often is, and can be. Beyond and as a part of that marginalization, birth is construed to be grotesque and/or farcical (as you point out). It is so tired, this trope of a woman screaming hysterically at her doctor that she wants to kill him, her husband fainting in the corner. I am ready for a new image, a new language – one that at least attempts to come closer to the event, even if it will inevitably fail to capture it.

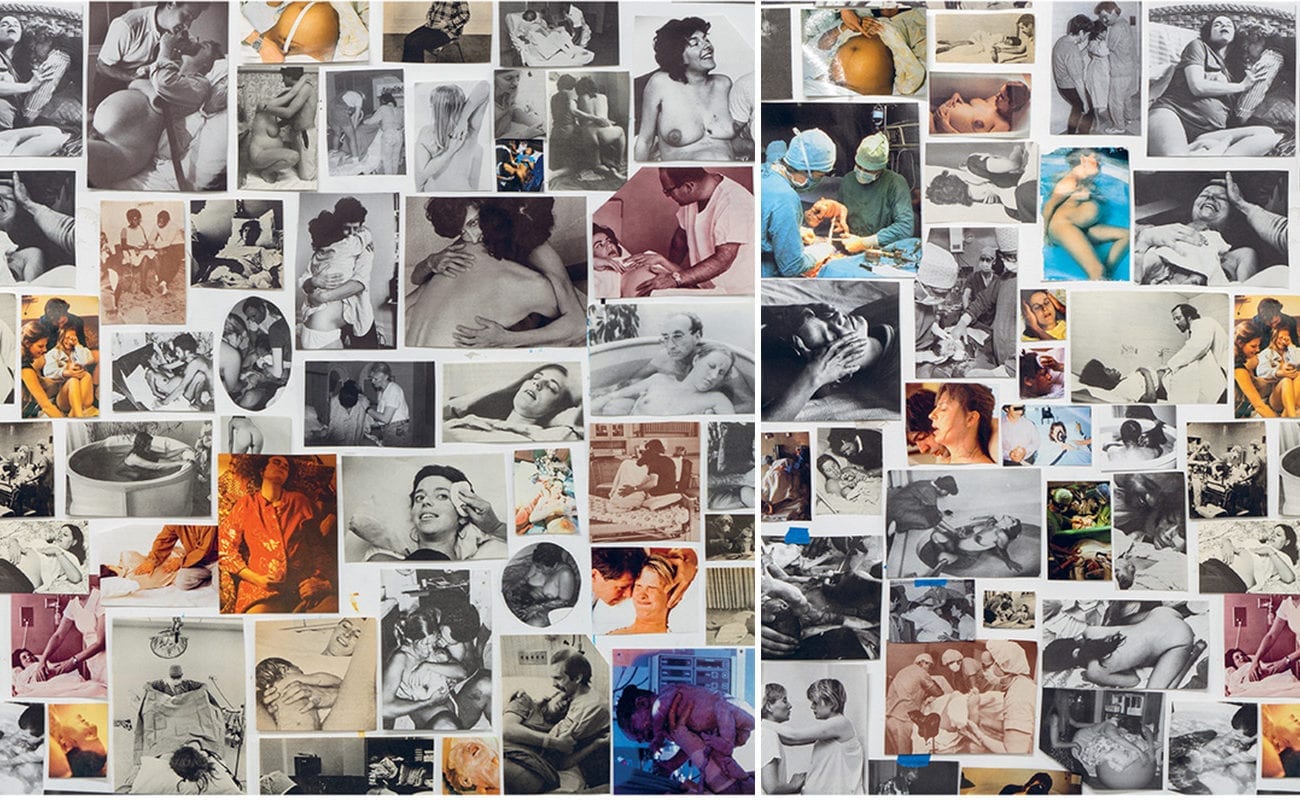

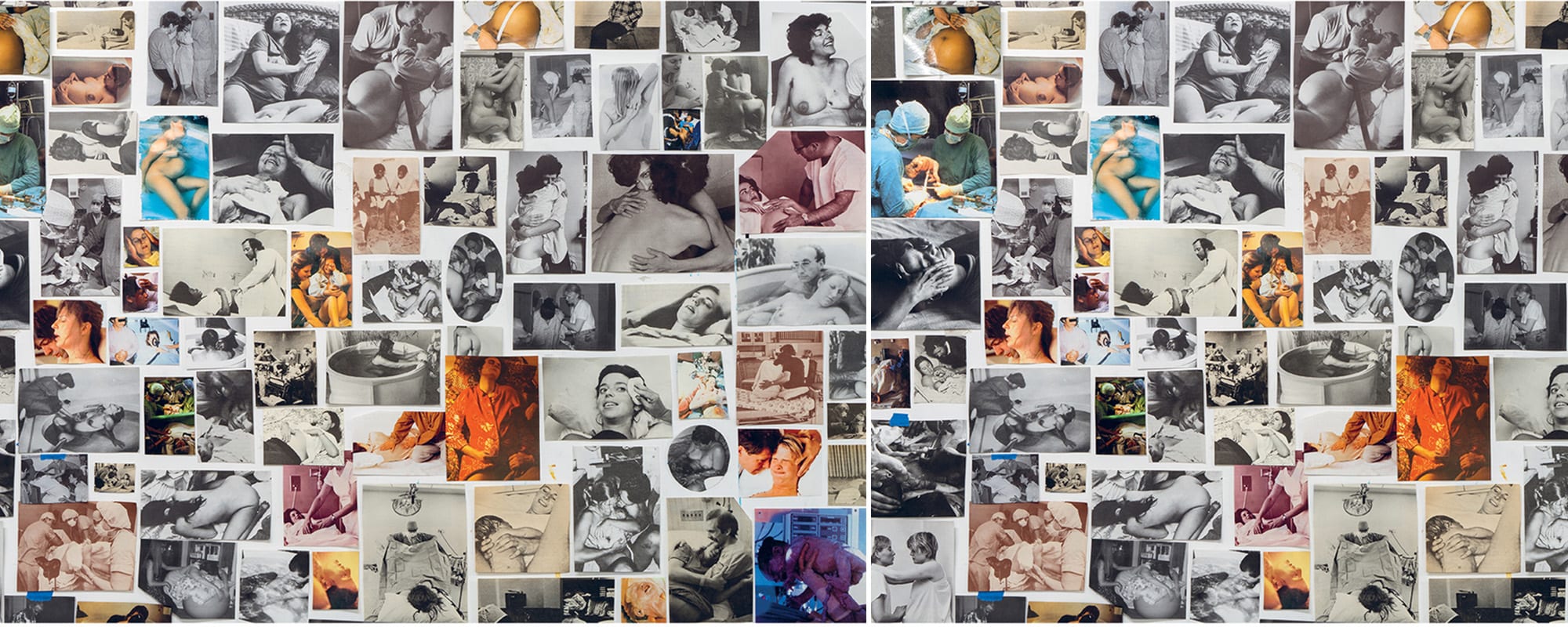

BF: The method of how you display your conceptual work is archival in approach, which manifests towards large collage pieces. I love the feel of how you look at images in volume. The display at MOMA for the “New Photography 2018” is an all-encompassing corridor of images from the series taped to the wall. The use of this display is meant to overwhelm in the same sense that the act of birth is all encompassing and well, overwhelming. It also, in its use of the tape and the massive collage reminds one of an open notebook- a very clever employ about the gravity of photography’s economic status. The de-limiting nature of casting the frame aside makes the images somehow quotidian and universal. This is a crucial choice for the material you are choosing to work with. It speaks about the democracy of the image and the process of birth itself. Can you give some insight on how you decided to display the project? Was there any reluctance on the part of the museum to give over the space for such a display? Do you see the work as a piece or the book displayed?

CW: I spent years working this way in the studio – images and blue tape everywhere, a way to see everything I had at once – only to feel that I needed to somehow clean up my act in the exhibition space. It took me a long time to collect the confidence and clarity I needed to identify that this way of working, this explosive, anti-compositional approach, was the work. It offered a way to keep these images whole, but also to seam them into a larger network; it spoke to saturation, contradictory narratives within photography, a democratization of images and contexts. It lined my insides up with my outsides.

To her great credit, Lucy Gallun (the curator) never hesitated. She encouraged this approach, offering full conviction and total openness. Aside from being a mother herself, I think she really understood how important it was to show these images in this, historically male, space: where thousands of people from all over the world would be circulating each week.

“I needed to identify that this way of working, this explosive, anti-compositional approach, was the work. It offered a way to keep these images whole, but also to seam them into a larger network; it spoke to saturation, contradictory narratives within photography, a democratization of images and contexts. It lined my insides up with my outsides.”

BF: When using the archival images in this capacity, one sees a subtle shift of color, the patina of age in which it is shifted down or has changed from the process of time and light. This usually qualifies for a type of nostalgia (a word that has come to glorify access and false narratives), but in doing so also makes a photographic image familiar. It also reminds one of a certain time such as the 80’s in the case of your mother’s images. I am reminded of some of the best selling photographic books from the time-though these books are not typical in what we think of as photographic books, for example, the “The Joy of Sex”, “The Joy of Photography” and the numerous soft porn books like “The Photographic Kama Sutra” even to a small degree “The Family of Man” etc. This surfaces in other bodies of your work such as “My Life As a Man” and “Looking Forward to Being Attacked”. What attracts you to using era-based images? Does it have to do with your age or is it simply and accumulation of images from a time in which these books were published in larger amplitude?

CW: Nostalgia: I worry about this word. It implies, I think, a miscast desire to be a part of a past not of one’s own, right? I am not totally exempt from this: I align my own feminist politics more with the generation before mine. But my work –this project included – isn’t necessarily about that romance. Rather, it is about wrestling with this kind of personal and ideological inheritance, understanding where it leaves me.

In this sense, it is vital to use the pictorial documents from that era. I don’t want to reference the thing sidelong; I want to touch it, in front of me. These images exist as found objects, in possession of their own lives and histories; many hands before my own have touched and studied them, perhaps anticipating their own births.

The diversity in their surfaces is critical in terms of the affect of the piece (how flat it would all read if the textures and tones were even!), and also in terms of describing these varied histories.

BF: I’m at once antagonistic to that term of nostalgia, but also embrace its possibilities to skew context and historicism. It was kind jest.

Returning to the body, I want to ask you about the process of childbirth and how you view its natural order, but if you can also speak about the themes of abjection and perhaps body horror that occur within the process from the female side. After all, your book begins with the questions about why we never ask about the process. Can you pontificate aloud about the process as it relates to the perception of otherness that society places the onus of its ritual? How do you relate to images of birth that are not directly related to your family?

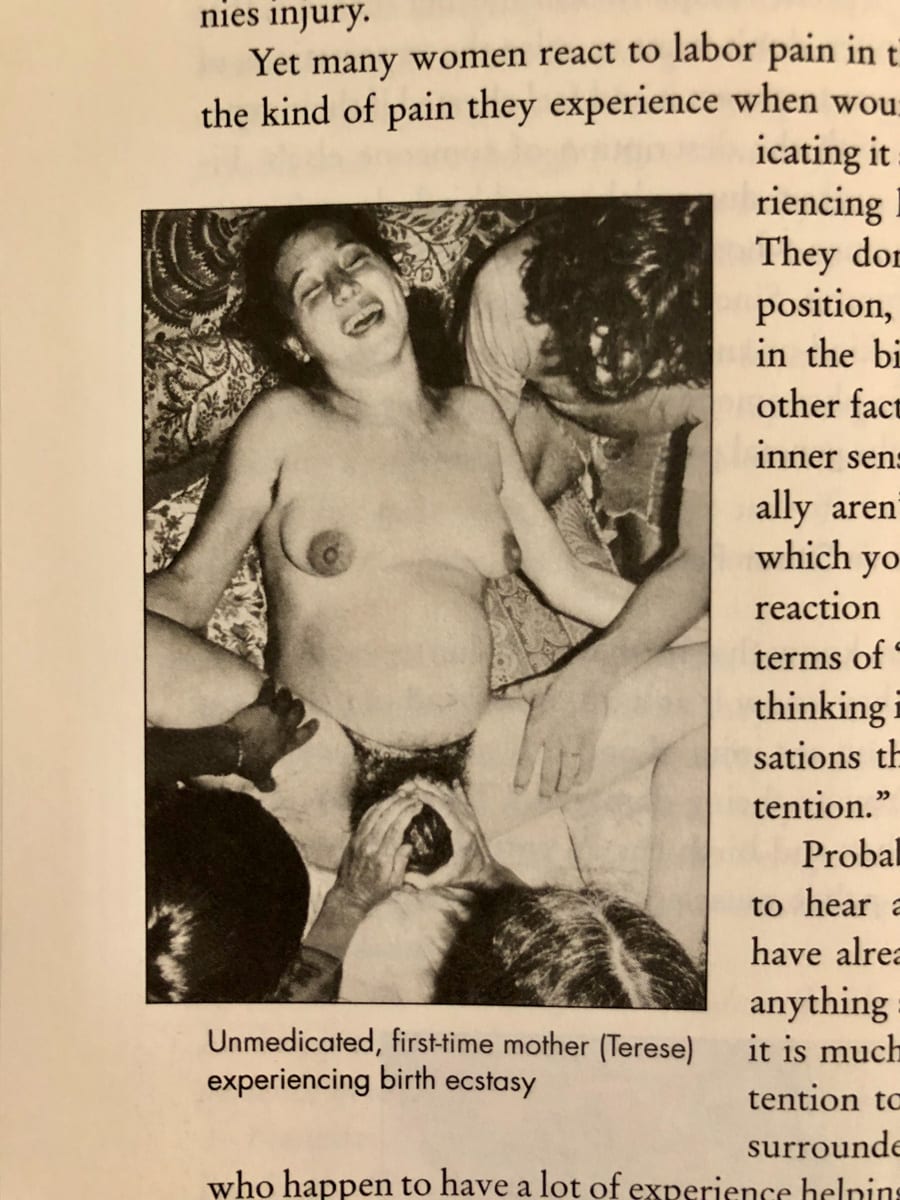

CW: When I was pregnant the first time and researching the process of birth, I came across a single image in Ina May Gaskin’s Guide to Childbirth. It was a picture of a woman giving birth, fully nude and surrounded by other bodies, from above. The head was coming out, she was smiling. Under her image read a single line, in the present tense: “Un-medicated, first-time mother Therese experiencing birth ecstasy.” I thought: what the fuck? I was, at that point thirty-two years old, eight months pregnant, and fairly well researched; I’d never seen anything resembling this narrative, or feeling.

This is not to suggest that euphoric or orgasmic births are the norm. But rather: there are many ways to experience birth, and the many conditions that affect that experience. Birth can be terrifying, painful and shockingly abject. The pain is deeper than any pain I’ve known; the surrender is complete; the pouring out is inevitable. I collected birth images throughout my second pregnancy, right up to the very end. It was often exhausting to be confronted with hundreds of birth images a day as I anticipated my own deliverance.

BF: That is really interesting as I was just reading an article somewhere about the importance of orgasmic births and masturbating during the process. A whole load of conflated images fell into my bean. Also, the May Gaskin quote and image, I cannot help but feel Theresa of Avignon has been employed as bizarrely meditative connotation between the orgasmic passion of receiving the word of God by Theresa and the narrative of birth. There is something in it, but due to religion, I am shutting that door now.

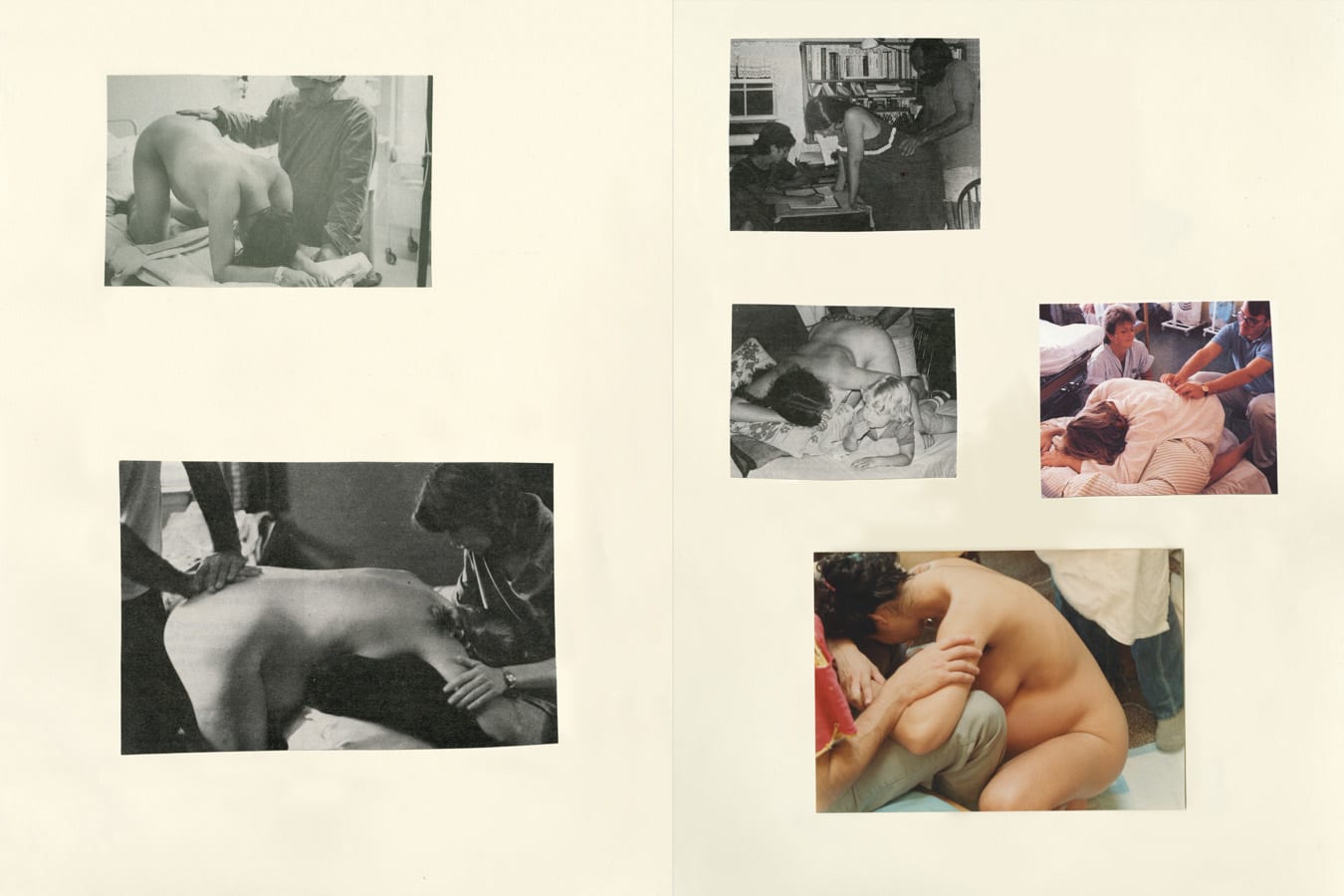

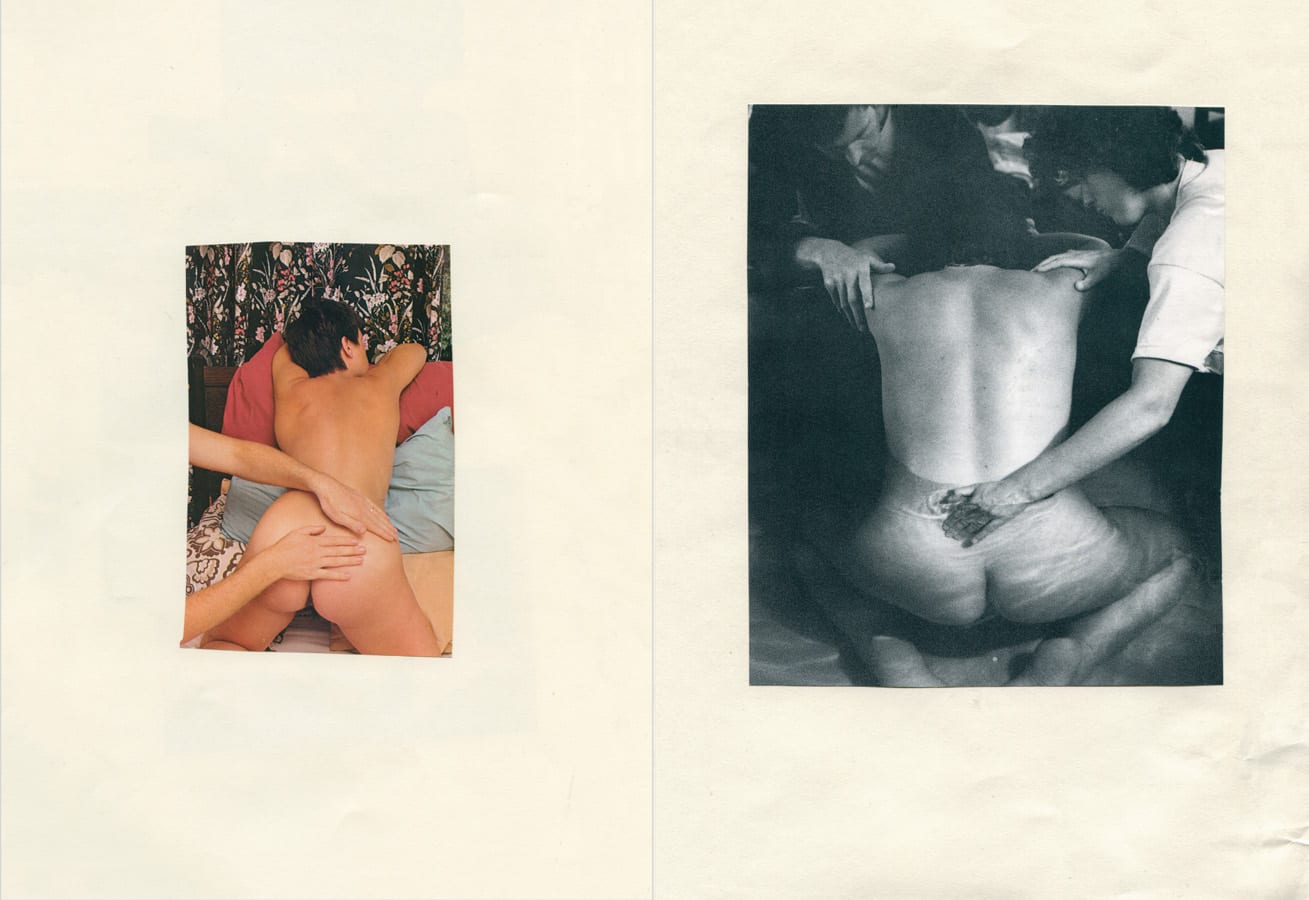

Gesture. When going over the book, I was initially taken with the concern expressed by father’s and birth nurses in the imagery. The idea that the birth is fairly solitary in scope…i.e. hospital, perhaps a partner and a few nurses is completely absent in your collation of the images. What I see instead is something of a theater. There are more characters on the stage than one usually assume at a birth. This is obviously in respect to what type of birth method one chooses, but the characters (I mean this politely) also act out strange manifestations of contortions, embraces and dynamic uses of their bodies as mothers, but also as supporting cast. The atmosphere of the room is palpable and when viewed from behind the lens, it takes on a shape of something primitive, tribal and again, universal. The sovereign nature becomes chaotic and pulsing. How does one explain the room? How does one explain their role of recording it?

“It wasn’t a planned effort; I don’t really remember him taking pictures. Those images he authored– when I did see them, some weeks later — propelled me into this project. It was an act of generosity.”

CW: My partner Luke Stettner (who is also an artist, whose work was written about in ASX in 2016) has such a meaningful role in this project, if unseen: he took hundreds of photographs during my first birth, as I labored out our now two-year-old son, Carlo. It wasn’t a planned effort; I don’t really remember him taking pictures. Those images he authored– when I did see them, some weeks later — propelled me into this project. It was an act of generosity.

My father appears in nearly all of the photographs of my mother giving birth. Other bodies surround her too, as there were close friends around for each birth. I am left to wonder: who took these pictures? And: who are all of these bodies that witnessed my coming (I only now recognize about half of them)? No one seems to be able to recall. What does it mean to give birth, naked and pushing, around people known to you (as opposed to anonymous health workers)? How does that congregation inform a birth (if not our understanding for the potential of birth through images)?

BF: Would I be wrong to see a strange violence, sexuality or relationship of control in these images?

CW: How could it not be so? However trite, my midwife told me after my water broke and spilled: the same energy that got this child in you will get him out. My body demanded that I loose its grip. My groans increased in resonance with every contraction; my body did involuntary things; my insides opened up and became my outsides. I remember thinking in that moment that this was the circle of life: sex to birth (rather than to death) and back again, folding in on itself.

BF: The theater of sex and birth, despite the obvious characterizations are two things that I resoundingly believe a man cannot understand. We orgasm differently and do not give birth. It’s very sad in a way that we men cannot be universal.

The list of questions not asked is extremely precise in conjuring up a pathos of empathy by their wording alone. Your work often incorporates text. At times, the text works in an incipit way where the question or words force possibilities in their opposite potential-that liminal space which margin walks from pen to productive discourse of its polarity. “Did you feel that your body was working against you”, “Did you forget that you had vomited” are but a few of the many questions which call into potential play a world ungoverned by bodily control, creating a schism between mind and vessel. This is of course one of the fundamental approaches to the trope of body horror-The dislocation between mind and body. I couldn’t see the questions on the wall for the exhibition, but perhaps I missed them. Did you include these questions for the MOMA exhibition? If not, why not and has anybody reacted to the work in uncomfortable terms?

CW: The text was specific to the book, which was a much more focused, restrained, and in some ways, nuanced project. The MoMA project held over two thousand images, none of them personal. The book, which contains dozens of images of my own mother in the process of giving birth, behaved as counterpoint: it behaved as a more intimate intervention into this material — what is more intimate than a witnessing of one’s own birth? — And a tribute to, and study of, my own mother. That kind of project allowed for, and even demanded, a textual component.

BF: If I had to choose one art historical reference for this project, it would be in line with Andrzej Zulawski’s “Possession” (1981). Do you have a set of reference in the art historical canon that you came across that you felt a kinship with while making the work?

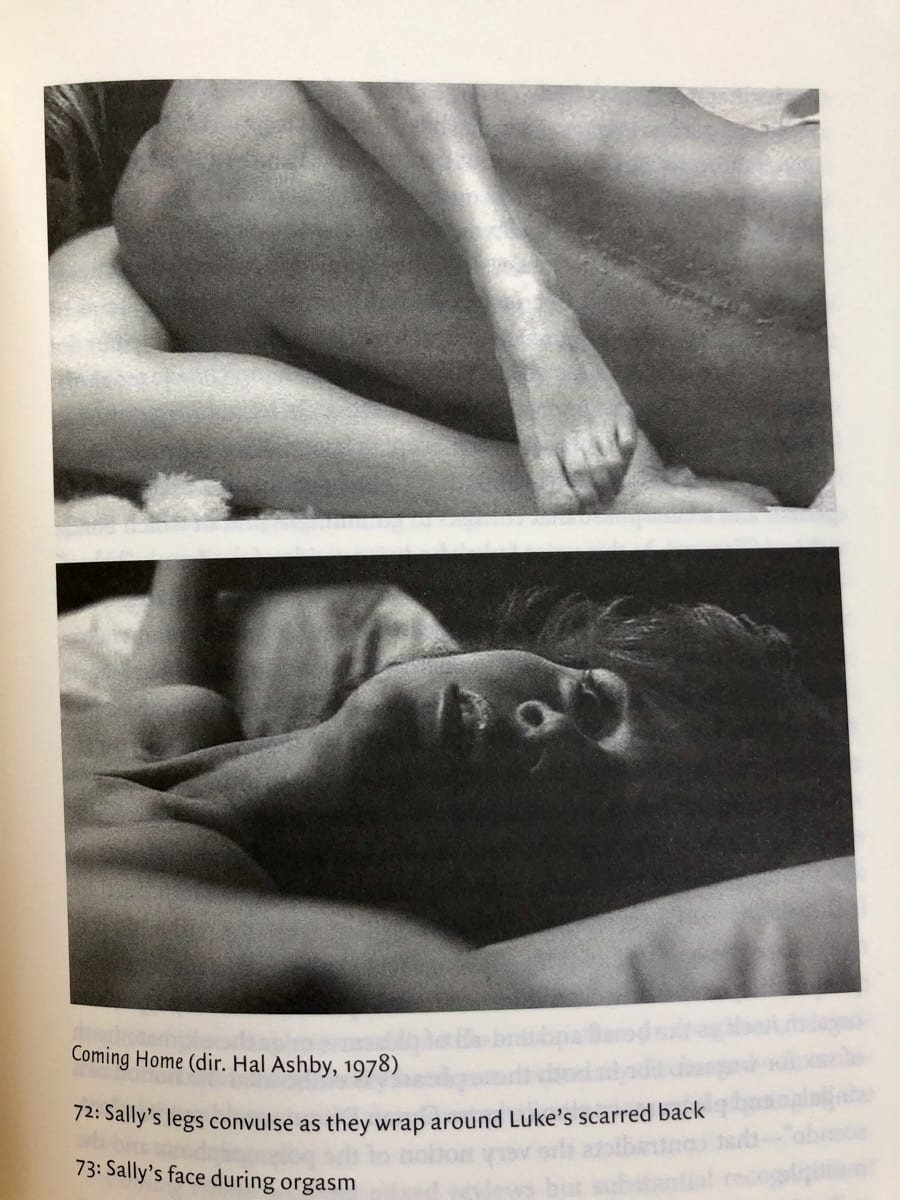

CW: I’ve never seen Possession; it is a horror film, right? I think my references are likely more rooted in women coming undone in pleasure onscreen. I saw Coming Home, the Hal Ashby film, when I was a teenager. Watching Jane Fonda have an orgasm with the paralyzed, wheelchair-bound Vietnam veteran Jon Voight…. I will never forget it. I saw Personal Best around the same time (another movie made in the mid 70s, by Robert Towne); the film is about two female pentathletes in training that they fall in love. Their sex scenes and their training scenes may as well be the same thing: protracted exercises in touching the ecstatic, punishing limits of their own bodies.

In more conventional art historical terms, Stan Brakhage’s 1959 experimental film Window Baby Water Moving and Frida Kahlo’s 1932 painting My Birth both influenced my thinking for how to depict the wonder and anguish (indeed death) that can occur within birth. I reference both of them in my writing.

BF: Ahh yes, Brakhage. I have to admit that as relaxed as I want to play this, that short did leave me a little mortified when I saw it the first time in my 20’s. You have got to see Possession when the time abides. Thank you for this insight!

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Brad Feuerhelm. Images @ Carmen Winant.)