“Asselin implicates the prize’s sponsor, using their financial app to display the real-time ballet that is the share price of both Bayer and Monsanto, neatly revealing the complicity of an entity that uses an arts prize to burnish its socially responsible credentials, while assisting a corporation that is a synonym for cynicism.”

The Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation (DBPF) prize states that it is awarded to the photographer who is “felt to have significantly contributed to the medium of photography” in the previous year. In an ever-shrinking and more professionalised photographical pond, the desire or even ability to critique such claims is severely limited. The suggestion is that since we know it’s a game, we should therefore treat no award, prize or honour as anything more serious than the latest shiny medal on a dictator’s son’s uniform. Except that those who promote such gongs couch their bestowals as recognition for outstanding X or groundbreaking Y. The game doesn’t sound as if it considers itself a game.

The prize’s format sees four photographic artists sharing space across two floors of The Photographers’ Gallery, London, with each given the chance to re-present the work for which they have been nominated. The chosen artists are Batia Suter, Rafal Milach, Mathieu Asselin and Luke Willis Thompson. That this year’s selection is seen by many as being highly political is surely testament to the historic dominance of politically opaque, introspective work.

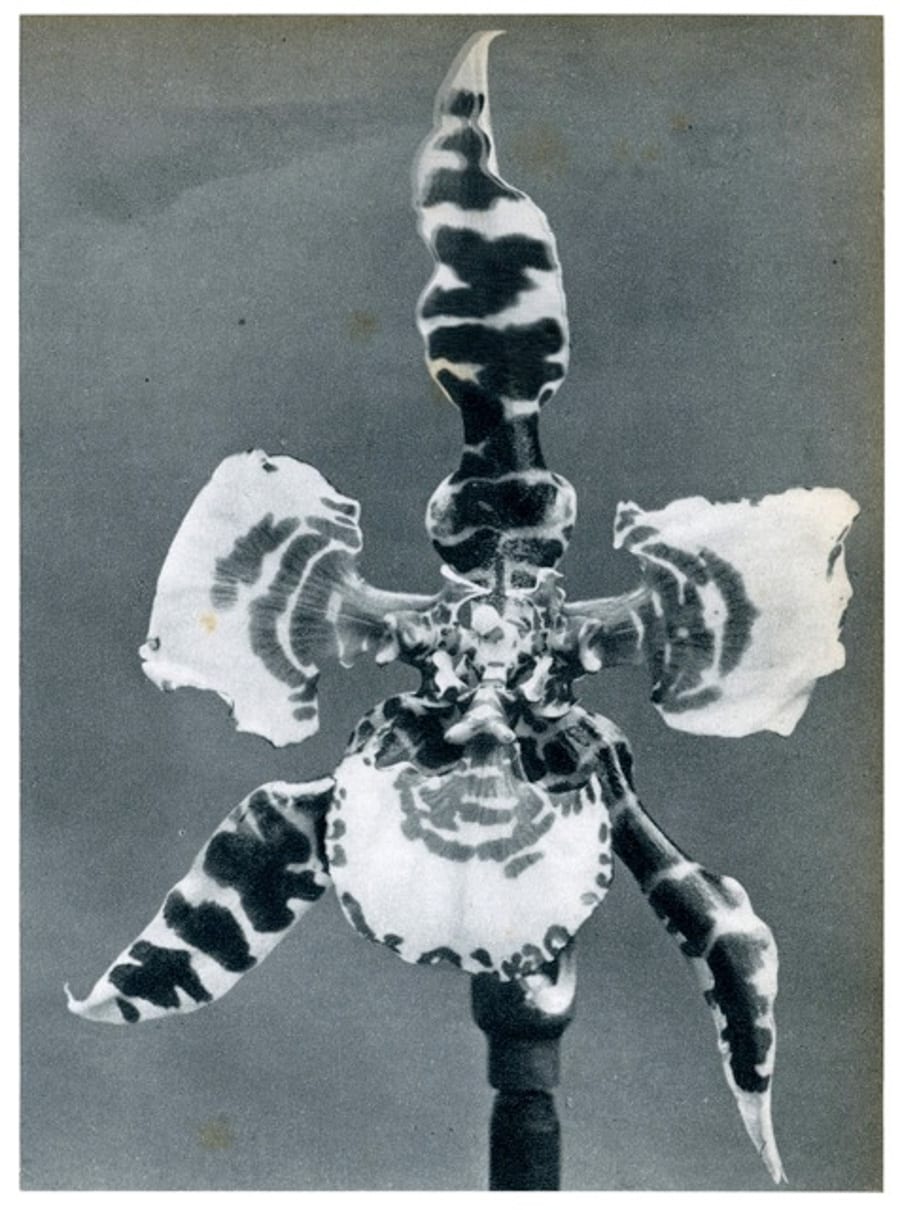

Grand claims are made for Batia Suter’s book Parallel Encyclopaedia #2 (Roma, 2016). Chief among them that by re-situating found images in new contexts the Swiss artist writes with images and in doing so generates new iconographies. Transferred from page to wall, Suter fills the walls with pinned up black & white images of kaleidoscopic scope. Free of narrative or any clear way in or out, the appropriated images fill our field of vision. Yet what may work on an incremental, page by page basis, falls somewhat flat when all can be swiftly taken in at a glance. Fished out from their arrangement across spread pages, the voluminous catch gasps on the dry white walls, struggling to raise much beyond a slightly bemused inspection.

Polish photographer Rafal Milach’s exhibition, entitled Refusal, examines systems of authority and thought control in post-communist nations and in so doing demonstrates the extent of government micro-management of propaganda and life. Milach presents images of false promise, wrecked towers, and toys supposedly designed to open young minds to possibility and imagination. Utopian architecture, children and damaged landscapes appear deeply entwined. Has very similar work been seen before? Yes. However, Milach’s image of a dead sparrow in an office swiftly abandoned by TV broadcasters loyal to Georgia’s former president is a particularly arresting one. A vision of sudden beauty and brief freedom casually snuffed out. One, no doubt, among many.

“But what will not go away is the sense that this is yet another artwork in which black trauma functions as ready-to-wear cultural clothing. Reynolds is known because she refused to be silenced. Yet autoportrait sees her both speechless and distanced into black and white film. Rendered art, thus safe. Detached. Disconnected. Inert.”

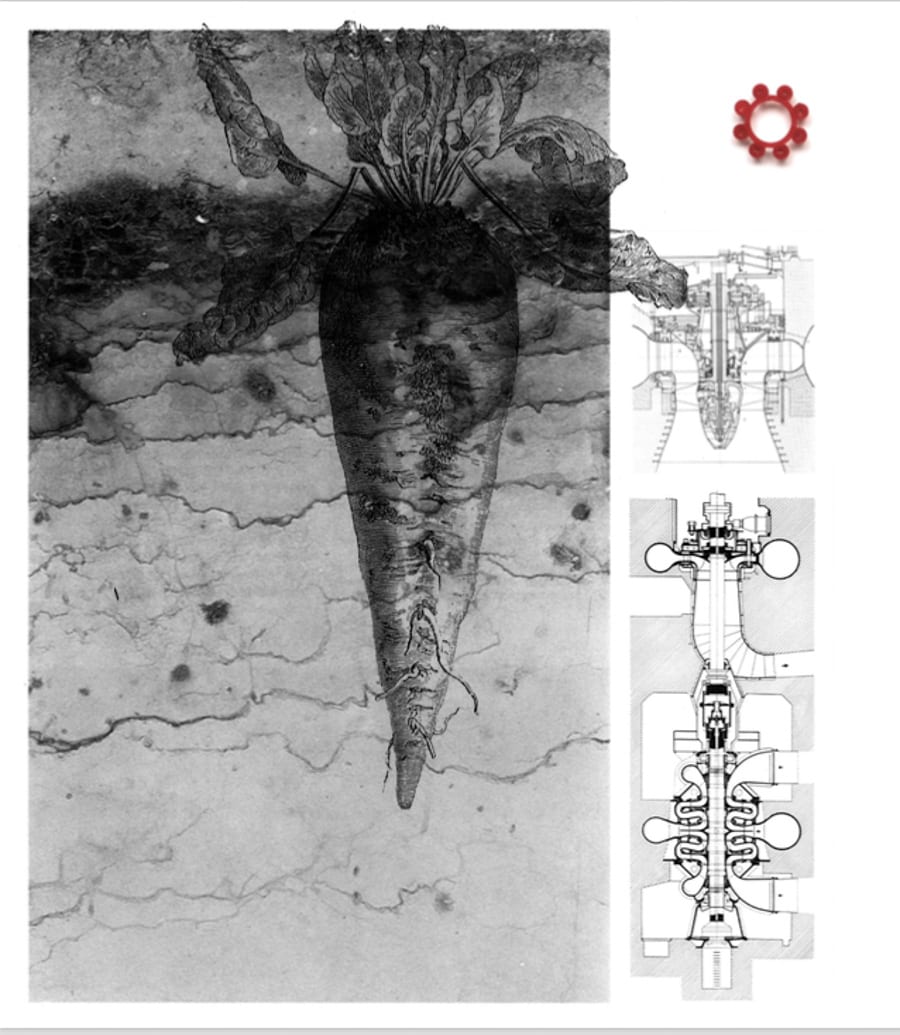

Mathieu Asselin’s polemical volume, Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation (Actes Sud, 2017), assails the aforementioned maker and peddler of toxins – including, but not limited to: DDT, PCBs, Agent Orange and GM seeds. Transferring a book-work to gallery walls is fraught with difficulty, however Asselin takes the opportunity to present a new ‘chapter’ based on recent events. Namely, German bio-chem colossus Bayer’s proposed merger with Monsanto – a deal that would be the world’s most expensive, should it complete. Asselin implicates the prize’s sponsor, using their financial app to display the real-time ballet that is the share price of both Bayer and Monsanto, neatly revealing the complicity of an entity that uses an arts prize to burnish its socially responsible credentials, while assisting a corporation that is a synonym for cynicism.

Yet as with Suter, the compendiousness of the bookwork for which Asselin is nominated cannot be replicated in the gallery. It’s only to be hoped that the works present lead people toward the French-Venezuelan’s award-winning book, being a merciless exposure of an organisation whose products have sewn human and environmental despoliation, varnished beneath layers of duplicitous PR. One thing to consider: Asselin uses photography as a tool of investigation, and does so to great effect. But we might question the extent to which the work pushes at any photographic boundaries. While also acknowledging that perhaps it does not need to…

The most interesting work on display is also the simplest and the most problematic. Luke Willis Thompson’s autoportrait is that of a young black woman, Diamond Reynolds. Presented as a collaboration between Reynolds and Thompson, autoportrait is couched as a response, a ‘sister-image,’ to Reynolds’ self-portrayal in her live Facebooking of the immediate aftermath of the shooting of her partner, Philando Castile, by a Minnesota police officer.

Filmed using Kodak 35mm Double-X black-and-white (a not insignificant choice) the loud whirr of the projector’s cooling fan contrasts with Reynolds’ static silence, as does the proudly analogue nature of the monochrome with the digitality of a live Facebook feed. Through mechanical flicker, Reynolds speaks soundlessly to herself, or us, or Castile. Split into two parts, Reynolds is seen first in close 3/4 portrait and minutes later at distance. The suggestion is of time passing. Of shifting places. Or of multiple watchers. As an unadorned monument to the private endurance of grief, it is initially extremely effective.

What will not go away is the sense that this is yet another artwork in which black trauma functions as ready-to-wear cultural clothing. (In the footsteps of Dana Schutz’s painting of the photograph of the mutilated body of Emmet Till, a black teen beaten and lynched in Mississippi in 1955, exhibited at the 2017 Whitney Biennial.) Reynolds is known because she refused to be silenced. Yet autoportrait sees her both speechless and distanced into black and white film. Rendered art, thus safe. Detached. Disconnected. Inert.

We must also ask, if this work is truly a collaboration, as it is repeatedly described as being, why is Reynolds not a co-nominee with Willis Thompson? We might further ask why the London-based, New Zealand-born artist felt he had to look abroad for an example of black suffering, of black death as commodity, as inevitability, as natural fact.

This year’s DBPF prize presents us with a variety of refusals: of fixity; of control; of lies; of engagement. Which will triumph? We decline to speculate.

The Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2018 is on display at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, until 3 June 2018.

(All Rights Reserved. Text @ Nick Scammell.)