‘A compilation of five interconnected projects, Dark Rooms moves in cycles: birth and death, acquiring and discarding, the banality of routine.’

Nigel Shafran is interested in the unremarkable; in details of life that persist below the threshold of reflection. His subject matter is immediate and close to hand: the things that surround him, that interest him and seem important in the moment. Dark Rooms is the second collection of Shafran’s work, following on from Edited Photographs, 1992-2004. Together, the two books map out a trajectory that begins in a hopeful reflection on life’s everyday rituals, and moves towards a more sombre assessment of its routines and endings.

Edited Photographs charts Shafran’s relationship with his partner Ruth from their early years together. The evolution of their domestic space and their life as a couple is given in images of renovation and repair, cooking, eating, and washing up, moving things around from one room to another, organising space, browsing in street markets and charity shops. There are glimpses of melancholy in the book – the neglected space of his father’s office, emptied of furniture – but Edited Photographs is, for the most part, a quiet affirmation of life, culminating in the birth of Shafran’s son.

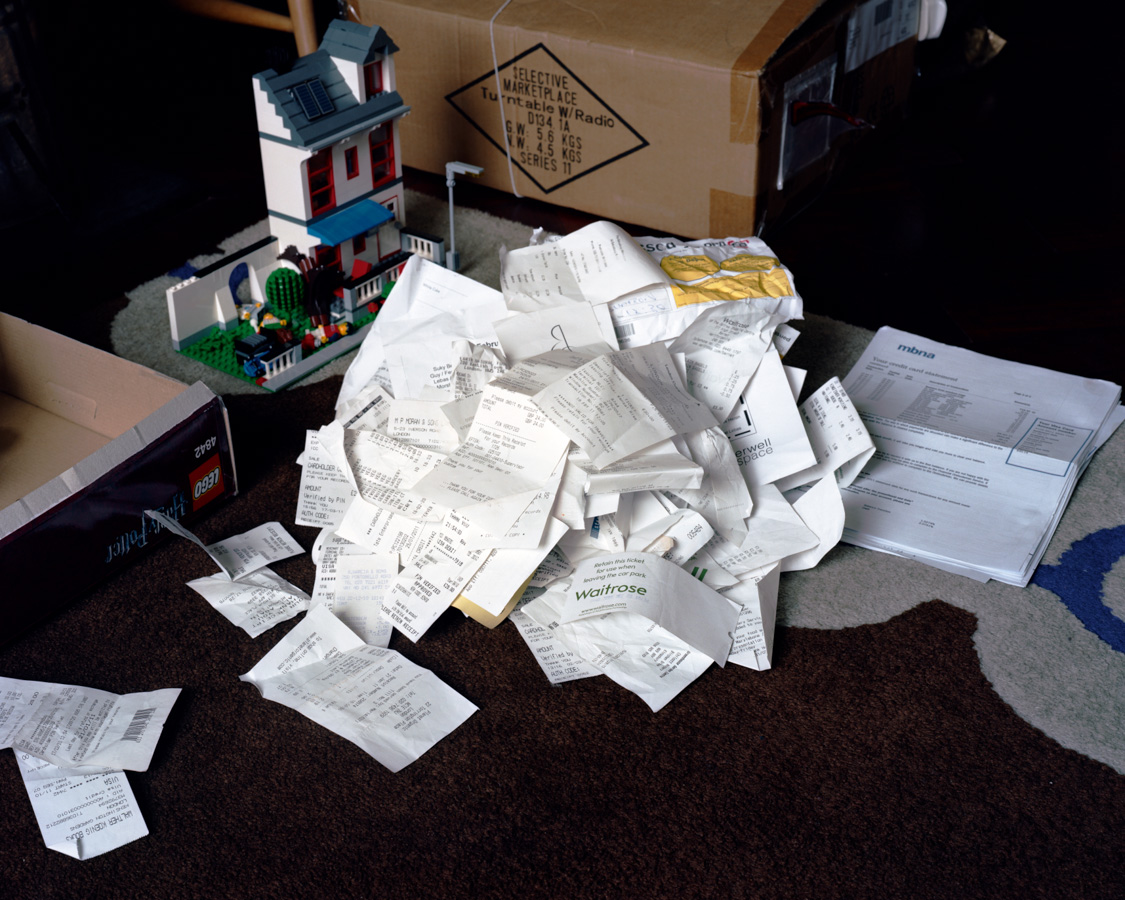

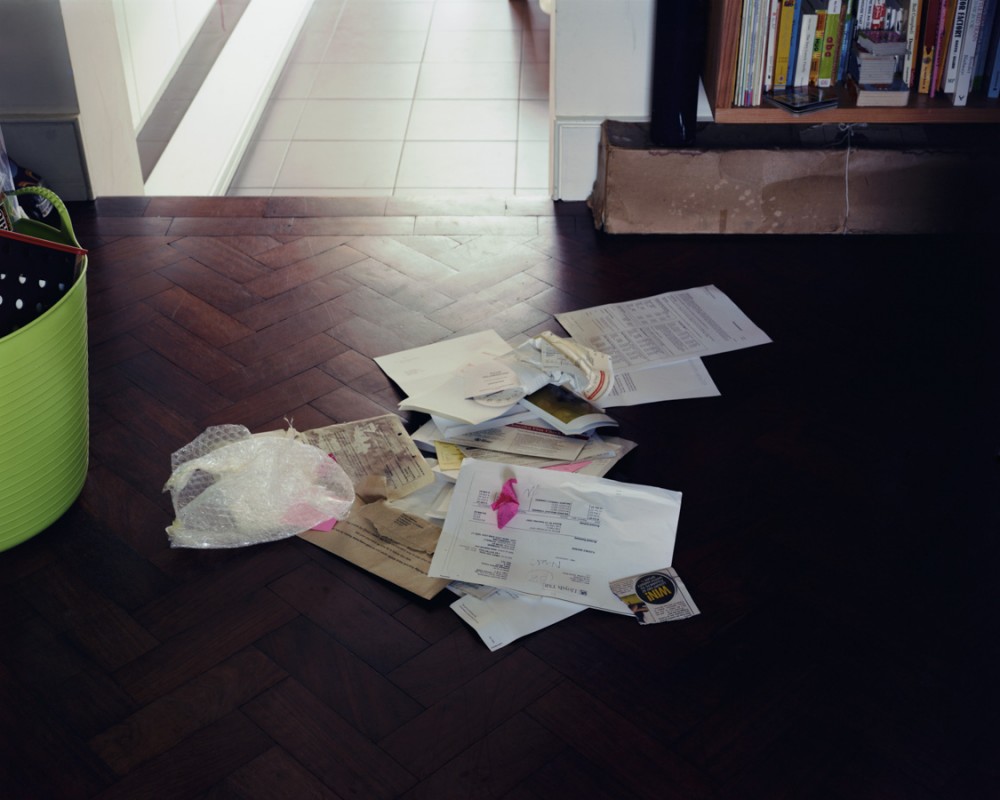

Dark Rooms follows a path in the opposite direction. A compilation of five interconnected projects, Dark Rooms moves in cycles: birth and death, acquiring and discarding, the banality of routine. In the house he has shared with his partner since 2001, and which we see restored in Edited Photographs, entropy has begun to creep in: cracks and damp patches appear, possessions pile up, objects show signs of wear and tear. The photographs of charity shops – where unwanted things get a new life – are replaced by images of mobility shops – shops peddling goods for the end of life, which their owners will probably only need to buy once.

Dark Rooms observes the mundane rhythms of day-to-day existence. Shafran photographs women on escalators, their faces set, their bodies contorted awkwardly, arms braced against the railing as though in preparation for an unpleasant fate awaiting them at the bottom. The daily shop is envisioned as a necessary intervention into personal space and personal life – a struggle against decisions that are made for us about what to eat and how to live. The book begins with a shots of anonymous groceries on the belt at the supermarket checkout, and ends with images of plastic packaging awaiting recycling. The message is a cheerless one: this is the way it comes from the shop, this is what you must get rid of when it’s finished. Photographs of Shafran’s family members appear like punctuation marks amidst these reminders of the outside forces that organise our lives.

Bracketed by the death of both of his parents, Dark Rooms is a meditation on the cyclical nature of life, on the way that things reach the end of their useful existence and begin, quietly, to slip back into entropy and decay. But there is also beauty and serenity to be found here, in the portrayal of Shafran’s own emotional life in the here now, and in the affirmation of what has been.

****

ES: I wanted to start by asking how Dark Rooms came about. Why did you feel that you needed to make another book?

NS: It’s the way I work: editing, sequencing, putting stuff together in Moleskin books, putting dummies together. Dark Rooms is a tiny amount of the pictures that I took over that time. You know that famous Walker Evans quote ‘Everything in me is funnelled into my work’? I do commercial work, which I don’t really feel is my work. This feels like my work. I’ll put a dummy together, and I’ll hone it, and I’ll make another one where it’s changed. The ordering of this, to me, has a kind of sense.

ES: Can you tell me about the choice of title?

NS: I like the meaning being kind of ambiguous. It went through different stages. It was Edited Photographs 2, but it’s not, really, it’s definitely a project on its own. It was Partial Eclipse at one stage, which I thought worked well. I have a whole list of other titles … titles are tricky, I always think. But then I thought: it’s in front of me, I don’t want to come up with some poetic thing, I just wanted something quite matter-of-fact, something that was in front of me. There are a lot of dark rooms in the book. And there is a connection to photography, I like that too.

ES: Why have you made domestic space your subject? What is it about it that interests you? Can you put words to that?

NS: Everything you do, there is a kind of political stance, in a way, isn’t there? To me, what I photograph is valid, at this time, in that sequence. I’m not really interested in the other stuff that we’re all meant to dream and aspire to. I just see it as a fake dream, really, most of the time.

ES: Do you mean like possessions, ‘luxury goods’, things like that?

NS: Yeah. Personally, it’s not for me. I think it’s all in front of you, really. I like stuff aging. I always seem to have liked that.

ES: Was there a sense of that when you were working on the book, or is that just how your interests have evolved?

NS: You get to an age, and I suppose there’s less in front of you than behind you. My parents both died during the making of this book. And I think there is a darkness about it. It has that kind of finality, hasn’t it? The pictures of the mobility shops, I wanted it to be new, unused, for sale items.

These are shops that no-one wants to go into. They’re always hidden, you never notice them, really, you never want to see them. There’s this kind of finality knowing that that is in store! It is in store for everyone, I suppose. It’s quite pessimistic, but also maybe kind of beautiful.

‘You know that famous Walker Evans quote ‘Everything in me is funnelled into my work’? I do commercial work, which I don’t really feel is my work. This feels like my work.’

ES: In Dark Rooms you engage repeatedly with the most repetitive, banal, activities of life – the shopping, the commuting …

NS: The choices.

ES: The way you present consumer choice in Edited Photographs is very cheerful. You’ve photographed all these wonderful open air markets, where everything is totally chaotic in an Aladdin’s cave kind of way, or these regimented, bright cheerful market stalls. It’s all plastic, but it looks like the vendors are really proud of their mini shops. In Dark Rooms, you’re photographing groceries on the checkout belts in shops like Budgen’s, and Asda, and Tesco – all these giant conglomerates, where you are literally just one more little cog in the wheel, handing over your money, the belt carries on, someone else follows you…

NS: That was taken with a tiny Canon Ixus, in the supermarkets with the best daylight, and the worst security, using a shopping trolley as a tripod!

ES: Is this your shopping or other people’s shopping?

NS: Mine isn’t in there. But it’s hopefully not too cynical or judgemental or anything. It wasn’t meant to be ‘Oh, look at that.’

ES: It’s really difficult to look at other people’s shopping without being a bit judgemental. The belt at the checkout is a bit like a catwalk for your consumer choices.

NS: To me, it’s also about depictions of food – modern day food and foodstuffs is of interest to me.

ES: When I think of depictions of modern day foodstuffs, I think of the pictures in a Jamie Oliver cookbook, where everything’s served on rustic wooden tables, or on slates. It’s the food ideal, isn’t it? Everything is freshly cooked, there’s not a plastic package in sight.

NS: Food is one of the things that keeps people separate, I guess. And it does keep people separate – separate classes of supermarket. All of the choices we make, it’s how we help define ourselves. Dark Rooms is about choices, and the times we live in, and decisions, and hurriedness, and packaging. I find it extraordinary that you go back and you throw half of the stuff away, straight in a bin. I find it slightly obscene, and pretty awful. It upsets me just buying something, so I try not to. You throw it straight in a bin, because it’s ‘hygienic’, or ‘clean’. It’s like a pack of cigarettes, isn’t it? They’re beautiful ‘til you pull them out of the wrapping, but before you do that, they’re beautiful objects, aren’t they?

ES: I often feel when I go into something like a pound shop, that I’m looking at stuff whose lifespan as landfill exceeds its moment of usefulness by a factor of about fifty million. But that sort of commentary is mostly absent from Dark Rooms. For me, these images weren’t comments on packaging, although you get into that towards the end …

NS: Or on people, hopefully. I hope I’m not being judgemental. And hopefully they are a bit beautiful occasionally.

ES: What is it that attracts you to particular configurations of things? Some of the photographs of shopping at the supermarket checkouts almost look contrived. I was wondering this while I was looking at them, thinking ‘has he actually made still lives on the belt?’

NS: The last ones in the book are still lives. But I understand what you’re saying: it all looks like it’s a little still life, ready, perfect, everything in place, doesn’t it? I suppose it’s slightly enhanced by the choices I make, and the light. Some are more inviting because of the composition, and the lighting, and the colours, and the choices, and the feel of movement. I can’t take it apart. I probably did a thousand pictures, but I just go ‘that one’, or ‘I’m attracted to that’.

ES: There’s also a sort of anthropological aspect coursing through the work – observations of people, of things, in very ordinary situations.

NS: I am interested in that idea of anthropology – choices, times we live in, they way that objects and people are different from other times. What’s in front of me is interesting to me, and how things age, and how I put work together, how it reads, and how effective it is, how it communicates. I like it to be as objective as possible.

‘David Niven’s A Matter of Life and Death, that film has always affected me. When the guardian angel rings his bell and life stops, I seem for some reason to have moments where I see things like that. I look at stuff from outside myself, sometimes.’

ES: Can you talk a bit about your attraction to decay and decline?

NS: It’s inevitable. There’s an inevitability about the mobility shop: mortality, inevitability, and an idea of consumerism still, towards your last days. I think that connects to the charity shop pictures as well: it’s the only shop where the goods choose the shop, as opposed to the shop choosing the goods! I remember going to a charity shop up the road and being slightly hit by the history of all this stuff, and memories that belonged to people who’d died, or moved on, and it’s all suddenly in this shop. And it looks like ghosts to me. I remember growing up, being seven or eight, and there used to be a series about Sherlock Holmes. I still remember the start, which was early Victorian film footage of people walking over a bridge on the Thames. In bed at night I used to think ‘all those people are dead now, and they’re there.’ I still remember that now. It’s a tricky balance between sentimentality – I don’t like my pictures to be sentimental.

ES: They’re very unsentimental.

NS: The pictures from where my mum used to live in Palm Springs, they weren’t done with any great artistry.

ES: They’re a very strange interval in the book, because you know you’re somewhere different. All of a sudden everything’s quite exotic, and there’s this pink bathroom.

NS: They look like insurance pictures, in a way. This was my mum’s stuff before she moved into a home. I just wanted to record it. I took pictures of mother’s drawings, from thirty, forty, fifty years ago.

ES: Was she an artist? Did she paint and draw?

NS: In a naïve way. There’s one picture where I was burning her chequebooks, before the house was moved out. I always think it’s like an army destroying all of its stuff before it moves on. It’s a slightly more personal take on the bigger picture. Liz Jobey talked about Dark Rooms as five interconnected sets of pictures, and putting myself in it occasionally just to ground the book. I’m very happy it seems to read how I was hoping it would read, which to me is a success in a way. As you say, it is quite dark, but hopefully, a bit life-affirming occasionally! There is beauty in it.

ES: It’s beautiful, certainly, but parts of it made me quite sad. But as you say, it is cyclical – this is so well expressed in the pictures of food shopping, the pictures of compost, the packaging that’s going to go into the recycling – all of these things are part of a cycle. There’s also a kind of monumental sculptural quality to many of the images. I was thinking specifically of these ones of plastic recycling towards the end; they look constructed, like still lives.

NS: Well I kind of made them, yeah. But I didn’t ‘construct’ them. Half the time I just threw them. And it’s the worst possible light in the whole house! Otherwise they would have looked too professional, they’d look like they were about the photo. They were taken to the left of the back of my computer, which is actually the darkest place in the house. And where we live, the train runs underneath us, and the exposures were so long that quite often a train would come along and ruin the exposure, and I’d have to get another sheet of film out. But you’re right, there is sadness in the book, because there is happiness and sadness in our lives. I have some sadness from my growing up time, and this is how it comes out, this is how I express myself.

ES: You start the book with consumer goods underneath bright light, and you end the book with their remains, in the moody half-light of a Dutch still life – a vanitas, which is a reflection on the futility of worldly goods and material objects.

NS: it’s part of this movement onwards, isn’t it? Dark Rooms explores that movement. That’s how I put this book together, in that way. The ordering expresses that, this order and movement, our daily lives, and this ending in darkness, which is the opposite of the ones in the beginning. And then these bits in between of my own life, and the things around me, help jolt it out from being too dry a set of pictures. David Niven’s A Matter of Life and Death, that film has always affected me. When the guardian angel rings his bell and life stops, I seem for some reason to have moments where I see things like that. I look at stuff from outside myself, sometimes. I don’t know what drives me, and I don’t want to analyse it. I’m better at taking pictures than I am at talking. My work is more succinct.

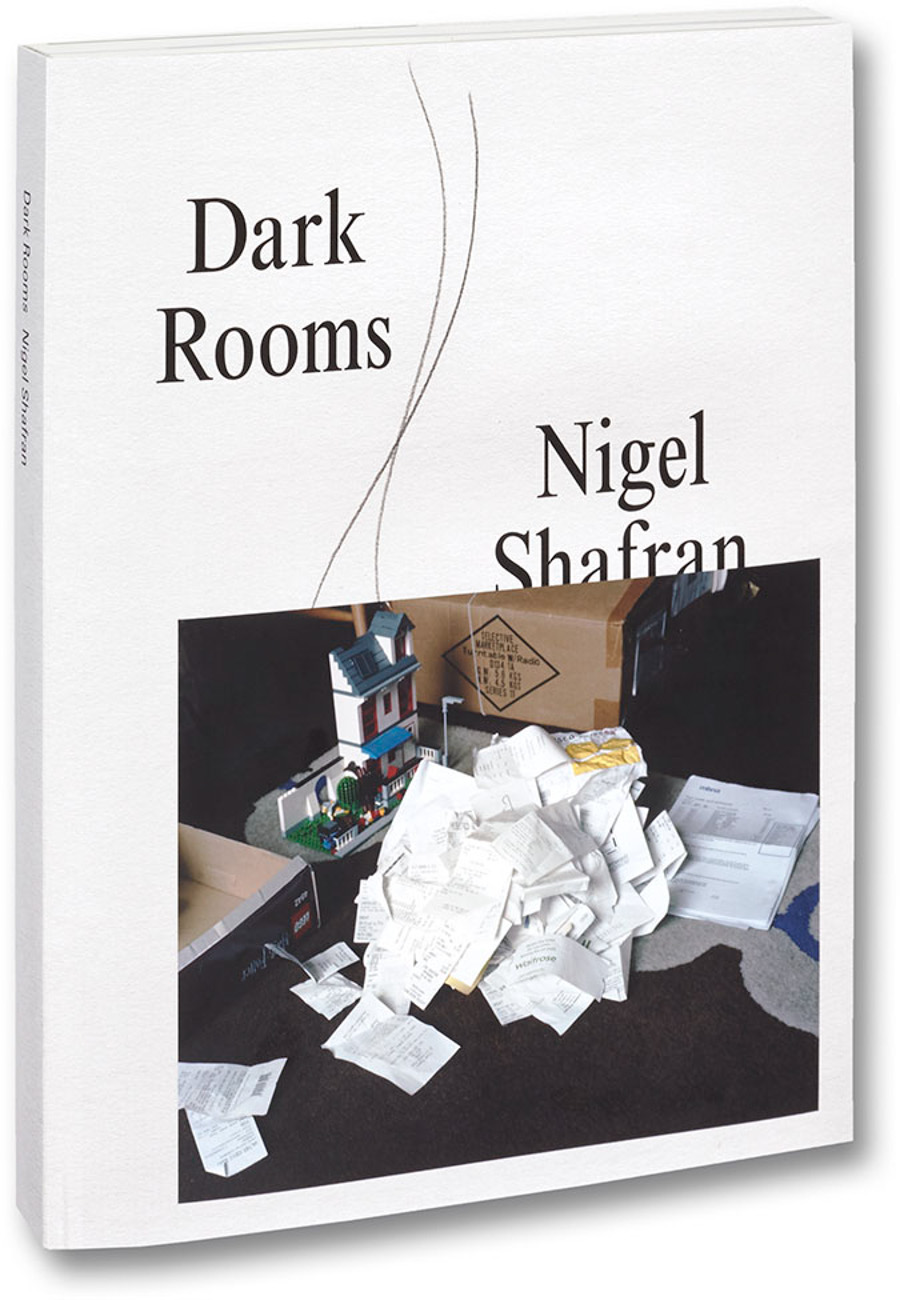

Dark Rooms

(All rights reserved. Text @ Eugenie Shinkle. Images @ Nigel Shafran.)