Estelle Hanania is what I would consider a sort of phenomenological anthropological photographer. When I say this, I mean to consider her an anthropologist with a camera interested in regarding a marginal culture shifts rather than a quotidian and beleaguered photographer attempting to secure an interesting topic.

Do we always disappear? Does custom evade its precarious certainty within the cascade of time by its punctuating dissolve? In considering the Nineteenth and twentieth centuries, industrialization and the camera; a certain susceptibility arises to document fleeting custom. One need only look back to Charles Negre’s Parisians under the duress of Baron Hausmann’s urban planning, Giorgio’s Sommer’s street venders at the time of the 1872 Vesuvius eruption, Juan Laurent’s Spanish peasantry of the Nineteenth Century, Karel Plcka’s documentation of the Slavic inter-war evaporation of folk traditions, Jose Ortiz-Echague’s Goya-like fascination of the pictorialist inconography during the pre-Franco years or perhaps best; the opus-gratuitous known as August Sander’s “People of the Twentieth Century” to question the certainty with which photographer’s seek to record what is to become the periphery of contemporary history challenged by events greater than a singular culture.

Perhaps it is the terminal speed of industry and capital that requires this of the photographer. Perhaps it was geographically speaking, one too many wars. My contention is that the pandemic of recording disappearances is not strictly European, but perhaps the mindset of the cataloguing of that notion is. In America, we have indeed seen their faces, but we see them with a dustbowl resplendency that seeks to push Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and the New Dealers into that of propaganda over that of the potential of “origin loss”. Within this, I suspect that the greater instigator of this necessity is conducted from the parapet or rather the turret of war. This phenomenon has a certain disappearance principle and why shouldn’t it; all “great” wars and shifting borders begin here as the forefront of hundreds of years of imperialism, which has shifted its loose sands across the trans-Atlantic divide. Empires have dwindled, wars have begun and ended. We assess the damage in what we leave behind in the gratuity of disappearances; the eradication of difference due to the defeat in war, the consumption of industrial consumerism, and perhaps the porous nature of tele-communicable mental borders along that of the physical ones that previously existed which were only to be carved up at the table of Versaille’s opulent mess.

Estelle Hanania is what I would consider a sort of phenomenological anthropological photographer. When I say this, I mean to consider her an Anthropologist with a camera interested in regarding a marginal culture shifts rather than a quotidian and beleaguered photographer attempting to secure an interesting topic. Her work with Europe’s traditional “pagan” cultures is well documented in her publications. Notably, her work “Glacee” consolidated her practice within this discourse to study of the dying embers of Europe’s Pagan past by way of its investigation. Though I adore the epic romanticism of Charles Freger’s “Wilder Mann” outing, Hanania’s work focused on remnant and resemblance of content within aesthetic values over that of pure romanticism and myth-building practice. Within her work, one was not left with the husk of charmed embodiment, but rather the particulars of the idea. Of note, Axel Hudt’s recent works straddle the line between the two. Let it be said, to all three, I am partial.

@ Estelle Hanania

@ Estelle Hanania

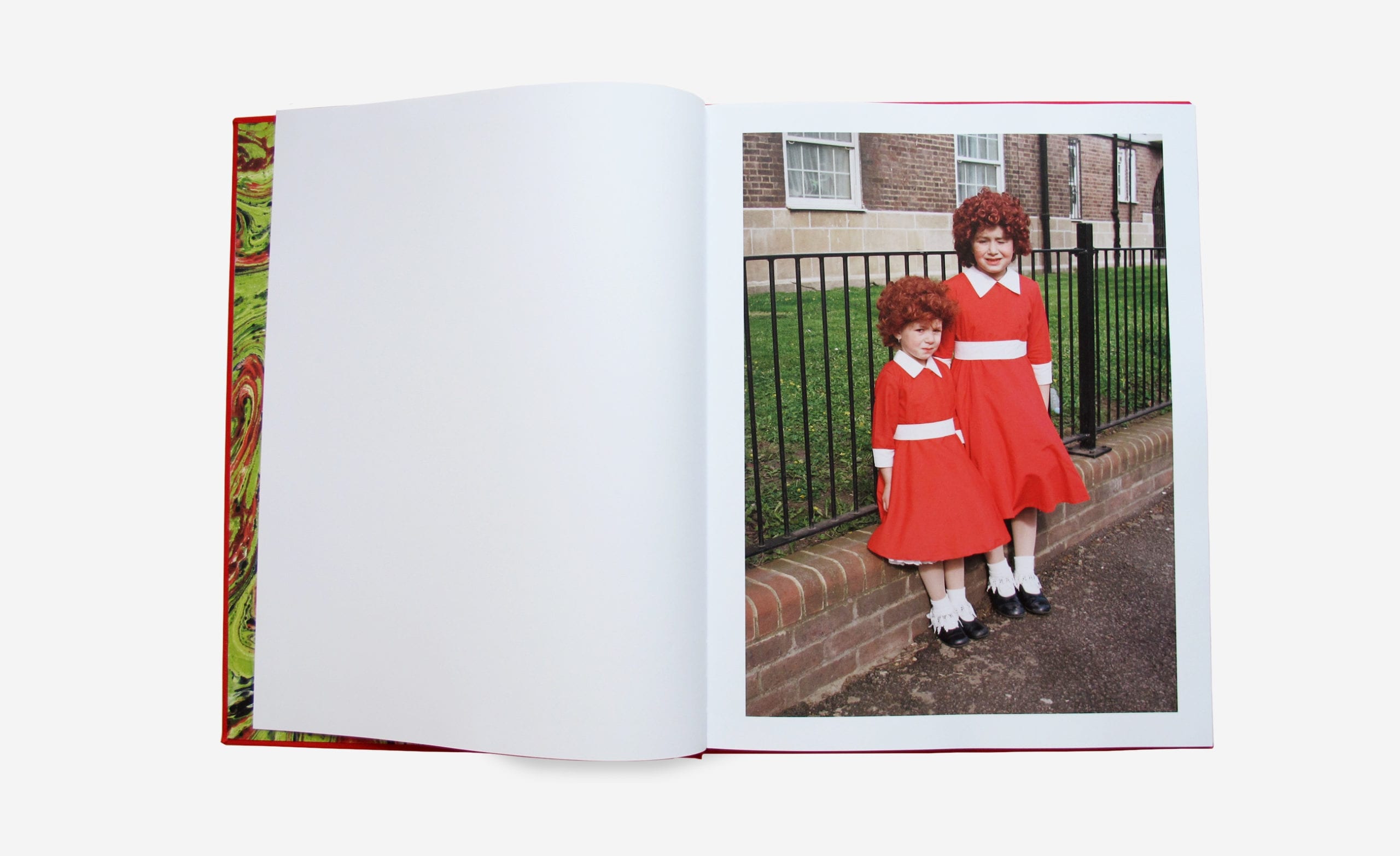

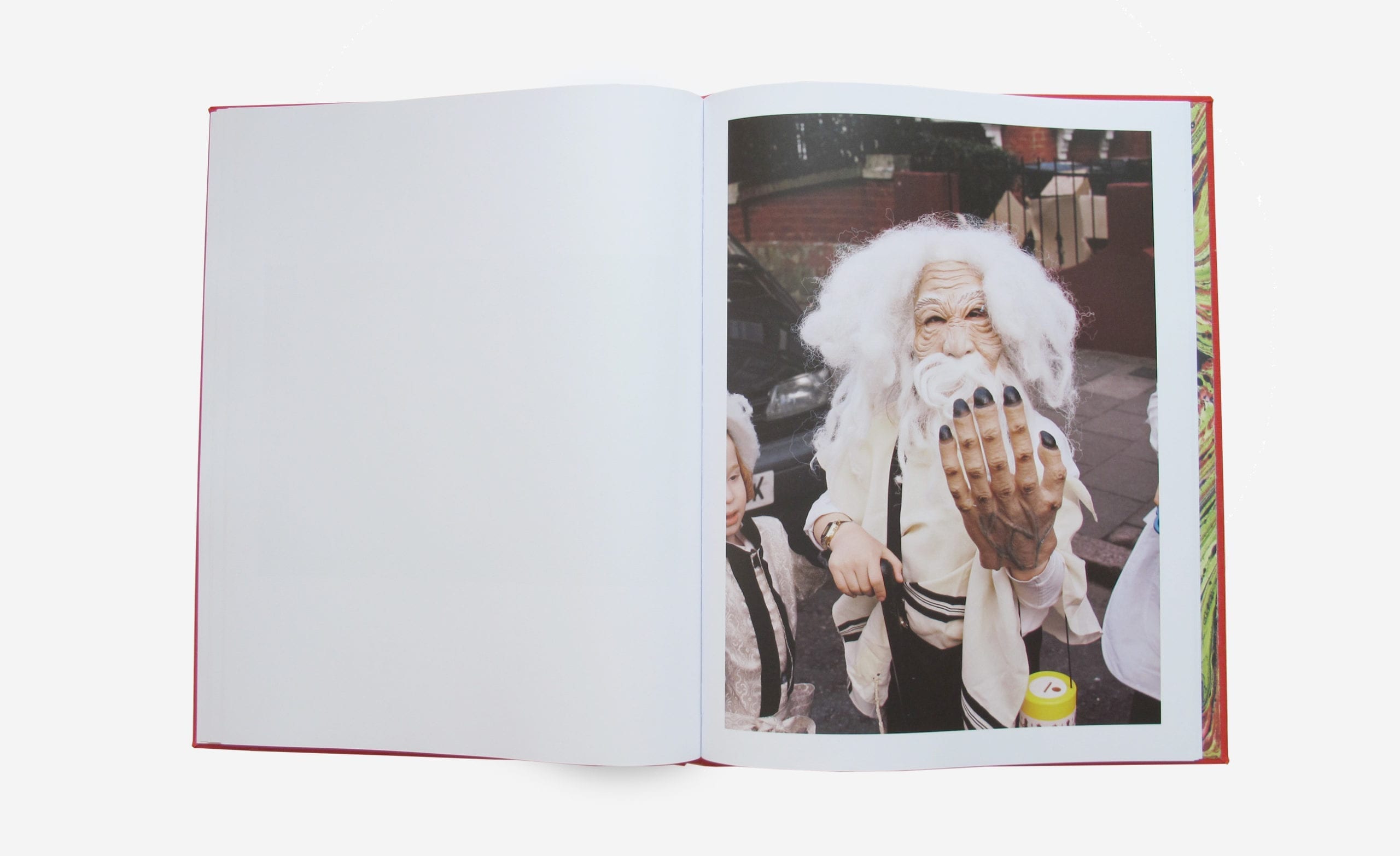

In “Happy Purim”, her work focuses on the Jewish holiday that still looks like as if Stamford Hill in North London descended into a proper Halloween sway of braggoddoggio.

In “Happy Purim”, her work focuses on the Jewish holiday that still looks like as if Stamford Hill in North London descended into a proper Halloween sway of braggoddoggio. As an American, I woefully mourn every October 31st in Europe. Halloween in America is a very important festivity for the shaping of aesthetics, jubilation, and necro-culture in America. In fact, it is one the one time of year that I am proud to be American, no matter if the tradition is borrowed from European customs of the past. It is almost a profoundly Hallmark America on Acid and Horror-two things that have shaped my own aesthetic interest and being. It is a phenomenon covered by Diane Arbus, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, and recently with Ossian Ward’s “Haunted Air”- a superb collection of vernacular Halloween documents.

Hanania’s work with Happy Purim is fairly straight-forward. I would hesitate to say it is documentary, as what the does that term even mean these days with notions of post-representation abound? There seems to radiate something else about it, either through consistent subject matter or perhaps the way it is handled. Perhaps it is the socio-cultural attaché of the focus group and the aforementioned iconoclastic potential of its previous near disappearance. The photographs themselves are not necessarily exceptional by standard of institutionalized art discourse. That being said, I have seen other work in magazines by Hanania that I consider to break some of the documentary feel for that of a stronger individual and artistic hand, which I prefer. Again, that is not to separate her art practice from that of her work. One would only need to look at the images she has made in collaboration with Sunn 0))) to note that these are fundamentally the same thing in her world, which I also champion her for. You have to think of these images within the larger trajectory of her work which, with this consistency, makes her vision strong and without the problematic fallacy that most contemporary photographer’s have: that of the “new”. The “new” in practice is a looming baroque monster of market ideology in which pressures often dictate that one’s work should stay the same, yet also shock with the new in their oeuvre to keep the chimps excited with their bags of peanuts. This stifles both the artists and the possibility of governing new thought. This misstep has ruined a great many career. “Its kind of like her groundbreaking work, but she has taken greater chances and grown with new trends of language, art and culture to push her vision meteorically”-said every nobody that never counted, ever.

What I portend here is that the work is rewarding itself for its consistency of conducting an investigation into type, custom and the potential of its disappearance without the dung droppings of the art maw. The same can be said of Shelter Press, whose output intrigues me for its slim program and consistently high-end product and back catalog. The potential of this book is to that of a time and place and will likely be seen in this capacity as have many books and bodies of work within Europe’s past. As we live in a continual state of anxiety marketed through never-ending warfare, hyper-consumerism and mass surveillance, perhaps our differences are should be more championed than our sameness. This does not suggest an advocacy for division, far from from it. It advocates acceptance with a fervent belief that the global mono-culture that is shoveled down our throats stems from the same agendas that creates the same wars and the same cultures of necessity that we have been forced to pander to previously. It may not represent a political chess-piece as a book, but it certainly accords a record of welcomed tradition that succeeds the monotony of culture we are forced to consume as good spending citizens.

Happy Purim

Estelle Hanania

Shelter Press

(All rights reserved. Text @ Brad Feuerhelm. Images @ Estelle Hanania.)