“Materiality has always been a strong thread in my work. This is manifest through an exploration of material properties in a sculptural sense , and the presence and play of materiality within the actual photographic surface.” – Tom Lovelace

The outer edge of Derby’s town centre appears as a fairly typical English, East Midlands urban landscape: a dense merging of terraced housing, shopfronts, disused factories and recently built, light industrial and business units. My short traverse across the city takes in a cheap parking lot, the central shopping area and on to the residential parts within the ring road. I arrive at my destination, a small group photography exhibition called ‘Except the Mirror’. It is here, I first encounter the strange, upside-down world of Tom Lovelace. The exhibition features a series of photographs from In Preparation (2011-12) where a pair of feet perched precariously on what seem like metal legs, concrete plinths or wooden stilts, all teeter on the edge of balance. This and the other work on show leaves me in a state of pleasant disorientation, echoing my tentative route around the town centre.

A few months later in Lovelace’s 2015 solo show, ‘this way up’, at Flowers Gallery in London, he revealed much more – a continuation of visual disorientation, highlighting a play with the processes of image making, materiality and the surfaces of perception. The exhibition was recently followed up with the release of a self-published book, also titled, ‘this way up’.

Sunil Shah: Last year must have been the culmination of some very concentrated activity in the studio?

Tom Lovelace: Absolutely. I wouldn’t have wanted it any other way. Deadlines and pending displays drag working ideas out of my head and jolt the making process to begin and evolve.

It would appear that a three-year cycle is taking form, as 2012 was very similar to this year: a solo show, an international residency, a cluster of group exhibitions and a publication. I am currently putting plans in place for 2017/2018, when I will stage another solo show. And, on the topic of books, I shall publish a culmination of 10 years work, folded into a book for 2017/18. It’s all very exciting.

SS: It is interesting how, regardless of the digital age, many photographers and artists are still fully immersed in processes and transformations and there is less anxiety about the ‘death’ of photography etc. In your practice how did the turn towards abstraction and materiality take place?

TL: Materiality has always been a strong thread in my work. This is manifest through an exploration of material properties in a sculptural sense (creating solely for the camera’s lens, most evident in my Unit 2 series), and the presence and play of materiality within the actual photographic surface. Relating to the former, I can distinctly recall being questioned as a ‘photographer’ whilst studying for my BA Photography in early 2000. At that time I was making, staging and performing a lot, but significantly, all with the eye of the camera in mind.

My recent photogram work best represents my exploration of materiality and the photographic surface. In these works I re-use found fabric, which has been affected by the suns rays. The presence of the actual material is extremely important in this work. So materiality has always been key to my practice. The same can be said in relation to abstraction and minimalism, yet these are more complex, and perhaps greater interests for me at the moment. To choose to explore the world around oneself, through minimalist aesthetics is quite simply a complex and difficult task to fulfil. That is the key driver for me currently, to explore, dig and interpret the world around me through abstract, minimalist strategies.

SS: The photobook is often considered the destination or end product for many. For some it IS the work. However, for you this publication is considered as an ‘exhibition catalogue’ for your recent show. With the gallery exhibition being temporary, the catalogue is typically left as a legacy, a gift or supplementary documentation to the gallery show. How does this book relate or differ in this respect? Especially as I suspect for an artist making work for the gallery, there are frustrations in translating that experience into print.

TL: From the outset my work has pivoted on the coming together of photography and the experience of three-dimensional display. How we experience forms of display, whether that be sculptural, performative, or an entire exhibition is important to me. I use photography to reinvent and re-present materials, objects and experiences and in this context, I have tried to use the pages of the book in the same way, to recycle and present a continuation of the exhibition itself.

Monuments, No.2, 2014

Monuments No.3, 2015

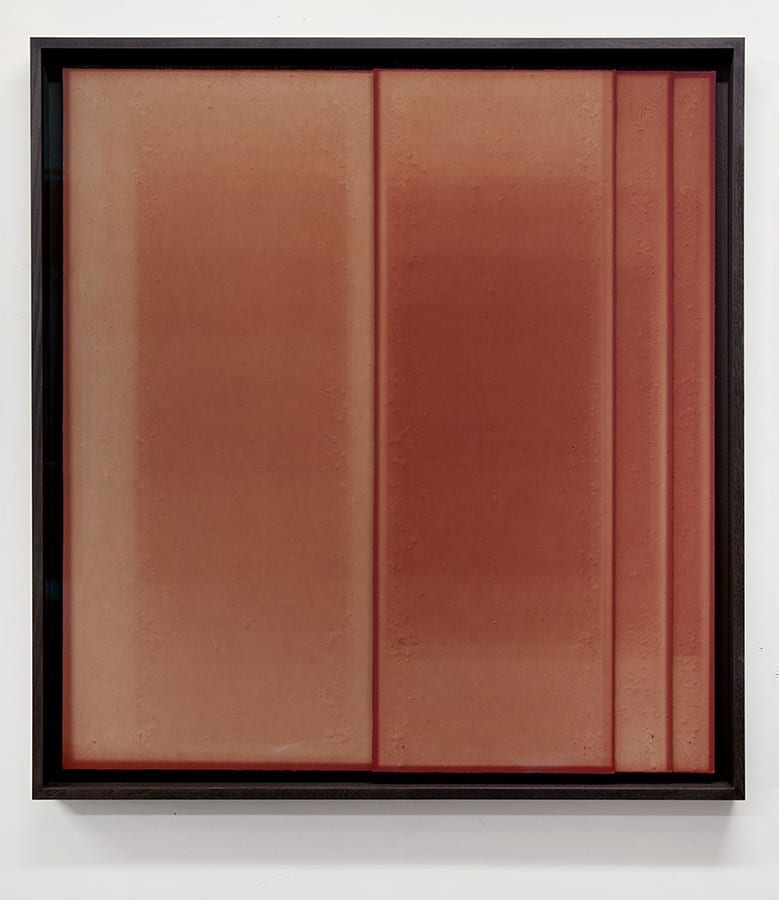

Untitled Red No. 3, 2015

“With all my images and objects, I attempt to take viewers to a certain tipping point at which there is a possibility to lose oneself in a particular work or installation.” – Tom Lovelace

I value traditional documentation of exhibitions, and you will see that I use these on my website, but I have not been interested in employing this type of imagery in my first two books; ‘Work Starts Here’ and ‘this way up’. I view these publications as just as much part of the exhibition, as opposed to existing as a supplementary object which is positioned parallel to it. You have highlighted a feeling shared by many when you touch upon the frustrations in translating ‘exhibition experience’. Simultaneously, you have also highlighted the beauty of staging an exhibition and why some people get so caught up in feeling that they must see and experience a particular show, and visit the church themselves. Further, it is extremely difficult to replicate those conditions; a sense of space and time once an exhibition has closed its doors for the last time.

SS: The book is unconventional, in some respects – being based on the concept of addressing the exhibition retrospectively, abstracting its form and to some degree revealing your work and processes through the essay ‘Snip Snip’ by Rye Dag Holmboe. Although for some your work might be difficult to understand, for others it may exist as a world in itself, without any text or signposting, I guess there is no right or wrong way to interpret these works?

TL: With all my images and objects, I attempt to take viewers to a certain tipping point at which there is a possibility to lose oneself in a particular work or installation. The exhibition ‘this way up’ pivoted on strategies of simplicity where all obvious signposts were removed. Some works pointed in on themselves and oscillated between being open and closed, whilst others where collapsing. As a collection, a sense of obfuscation was present.

I was interested in momentarily relieving highly functional objects of their practical duties, in turn allowing them to slip into a world which has its own set of visual rules and properties and significantly, a place where viewers could become lost and disorientated within the work. Equally Rye’s text, Snip Snip has been a revelation for me. He very simply, yet elegantly dismantles the work both logistically and theoretically, drawing attention to materials, processes and the origins of objects. It is a revealing text into both process and concept. There is a deceptive simplicity to the body of work, which Rye brilliantly exposes.

SS: It is interesting how the reference to Alice in Wonderland is made in the essay. In many ways much of your work to the untrained eye may seem nonsensical and absurd; this disorientation is a part of a world you create in your work. It takes us somewhere we are unfamiliar with which is an interesting trope of photography, where the imagination is activated through a perplexing experience. Is this other place what you are looking for in your process? To paraphrase Alice in the essay: “If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense.”

TL: I am smiling as your words could form the perfect introduction to my practice! I was surprised when Rye used Alice in Wonderland as a reference, surprised that the connection had not previously been made. I extract the highly familiar; the objects, places and experiences from under our nose, and then twist and turn these until I am able to rework them to a stage where they perpetually oscillate between the mundane and the fantastical, the absurd and the perplexing. There is indeed an absurdity about the work, however this is coupled with a serious re-evaluation of the object and image landscape around me. Form, function and identity are not taken for granted in my practice.

SS: In much of your work there are processes involved that are contingent to your ‘framing’ of the work into a finished piece. When we spoke once before, we discussed how one might get to a place where the work seems complete, at that moment in time, at least. When we are working with objects, photographically or not, there are positions, orientations, formats and displays to consider. It’s a difficult thing to unpack, as it is something that’s often based in or around intuition, experience and feeling perhaps?

TL: Unit 2 (2007 – 2009) is an anomaly within my practice as it is the only project where the final set of works have directly mirrored the designs at the outset. This work took a linear, clear trajectory resulting in a set of photographs which essentially pay homage to the concept drawings. All projects since have straddled with objects and images in constant evolution. Here, an initial seed of an idea is stretched, tossed and turned in the ‘framing’ of the work and when that framing takes place, is unknown. The ‘Monteluco Sole’ series would be the obvious example to use here. These particular photographs were taken in 2012, yet they are dated 2013. Taken during a residency with the Anna Mahler International Foundation in Spoleto, Italy in the summer of 2012, these photographs depict a set of chairs seemingly suspended from a tarmac ceiling. The films were developed in Rome, and then once back in London I made a set of prints that hung on my studio wall. I knew that a potential lay in these depicted objects. And then the following year, I turned one of the photographs upside down. Immediately the work crystalized, in a nonsensical way. By turning one of the chair legs upside down, in turn, the chair became the correct way up. Further, all sense of gravity was lost and this harmless, redundant metal object suddenly slipped into a new form, with new meaning and renewed energy. They were photographed in Italy in 2012, yet made, and complete the following year in south London. Hence, the accompanying dates significantly state 2013.

Interestingly now, there is nothing stopping the owner of these photographs to simply turn the works 180 degrees and display them in their original composition and form.

A further example of this evolution of objects and the significance of framing occurred this week at the New Art Centre, Roche Court, Salisbury. I was one of five artists exhibiting in the recent group exhibition Groundwork. I displayed a two-part sculpture entitled Brace, Brace along with a set of photographs displayed in the gallery. Brace, Brace would fall under the category of ‘sculpture’. During the de-installation process, as the technical team were slowly dismantling the structure, a beautiful unravelling process took place with the sculpture fluctuating between order and collapse. Over the next hour I documented this with my 35mm camera and I instinctively had a feeling that the resulting photographs would not only form a continuation of the sculpture, but might also exist as an entire set of two dimensional works. This is a prime example of how my work is driven, and in constant negotiation between the 2d and 3d interpretations of the world.

SS: You’ve mentioned how your work identifies and presents the fabric of photography through interfaces or points of slippage between perception and abstraction. In your own words, you are “pulling work apart, investigating and developing strategies that pivot on simple interpretations of the world… flipping orientation… looking at what already exists in the world… the ready-made” What appears sometimes as complex and serious is perhaps not so, there is a playfulness in your work.

TL: I attempt to make work that is translucent, metaphorically. On the one side, the underlying intention of my work is a serious exploration into photography; where photography exists, how the medium operates, and what it can achieve. The questioning continues. My research is underpinned by the history of the medium and what previous generations have done with a camera in hand. At the same time, I am a visual artist and I strive to make photographs and objects, which engage and rupture the imagination. The installation SWEEP is a clear example of this methodology. The work is rooted in Fox Talbot’s study from 1844, ‘The Open Door’, yet simultaneously, the resulting work displays a playfulness and humour. For me it is about a synthesis of these two elements.

Tom Lovelace lives and works in London. He studied Photography and Art History at the Bournemouth Arts Institute and Goldsmiths College, London. Recent solo exhibitions include Mirage Valley at Lendi Projects, Switzerland and this way up at Flowers Gallery, London. Lovelace is currently exhibiting in Frame Thy Fearful Symmetry at Collyer Bristow Gallery, London until 24 February 2016. this way up, Lovelace’s second self-published book was launched in November 2015. www.tomlovelace.co.uk

Sunil Shah (b.1969) is an artist and curator based in Oxford, UK. He is interested in the politics of photographic representation and conceptual post-documentary practices with relation to history, memory and identity.

(All rights reserved. Text @ Sunil Shah. Images @ Tom Lovelace.)