When Spanish dictator Francisco Franco died in 1975, decades of repressive cultural policy died with him. Swiftly, numerous counterculture movements sprang up to fill the void. La Movida Madrilena – ‘The Madrid Scene’ – was one of the first, and Alberto García-Alix was one of its pioneers.

I know you. You’re a lot like me – or at least, a lot like someone I used to be: the front of nonconformity thrown up at an early age, the drug abuse falling into place like part of the plan, and the camera always ready to capture the photogenic shine of what we thought was immortality. For a while, it’s beautiful, the haze and the squalor and the collateral damage of broken friendships, wasted talents, and lives ended far too soon. And then one day the bacchanal doesn’t look so pretty any more, and the ideals start to seem more like excuses. When the shine starts to wear off, it’s over. If you’re not already trapped, you walk away.

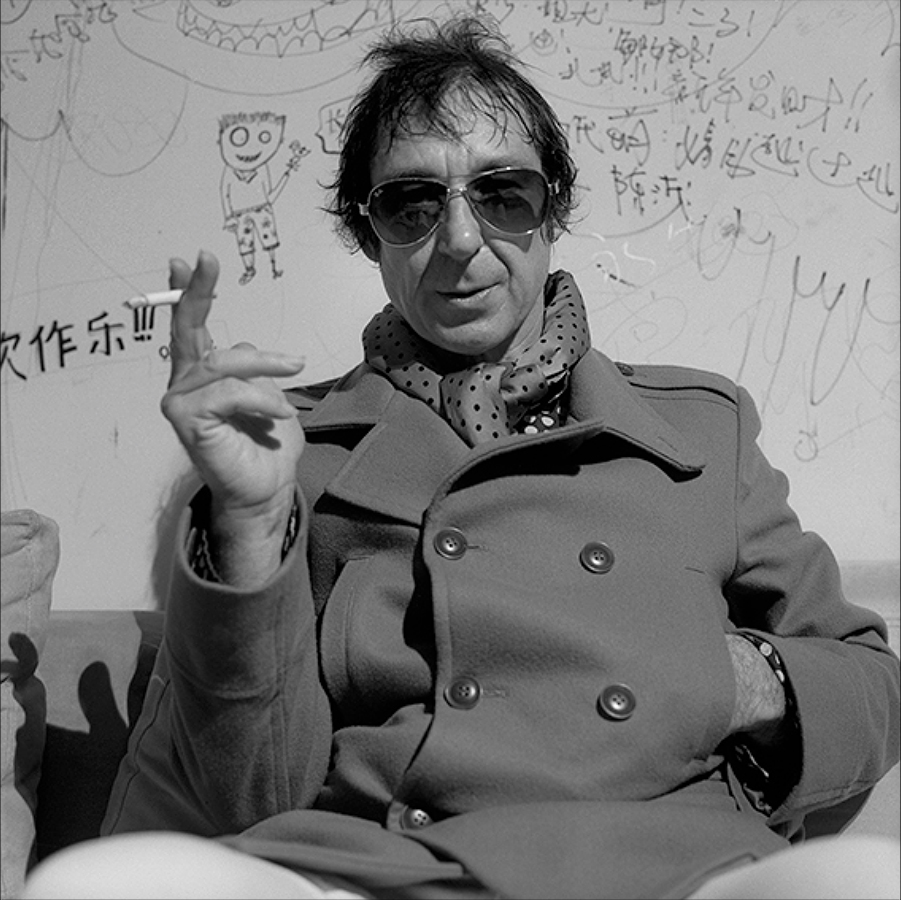

When Spanish dictator Francisco Franco died in 1975, decades of repressive cultural policy died with him. Swiftly, numerous counterculture movements sprang up to fill the void. La Movida Madrilena – ‘The Madrid Scene’ – was one of the first, and Alberto García-Alix was one of its pioneers.

Much of García-Alix’s early work is a record of La Movida’s more hedonistic face: the romance of a cultural revolution that was built around moment-to-moment existence and a politics of transgression that was, at least for some of its adherents, founded on nothing more substantial than an injunction to party as hard as possible. And there is no shortage of pictures documenting García-Alix’s early life: needles going into veins, squalid flats, guns and knives and heedless sex and the pinched, anxious face of addiction. We peer in voyeuristically and congratulate ourselves on our good decisions.

One day the bacchanal doesn’t look so pretty any more, and the ideals start to seem more like excuses. When the shine starts to wear off, it’s over. If you’re not already trapped, you walk away.

It’s far too easy to label García-Alix a kind of Spanish Larry Clark. But Clark’s bored suburban kids have little in common with García-Alix’s drug-addled revolutionaries, whose nihilistic lifestyles were born not out of ennui but out of a sense of social, political, and cultural possibility.

And in any case, Un Horizonte Falso isn’t this kind of book. Published alongside the exhibition of the same name held at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie de in Paris in 2014, Un Horizonte Falso casts a retrospective look over García-Alix’s own life and career.

‘Time should say a redeeming prayer for all of us’, reads a caption to one of the handful of portraits in Un Horizonte Falso. There’s no glamour here, no sentimentality, only faces frayed by time, weary and creased with disappointment. They crop up towards the end of the book, a small gathering of what we can only imagine are failed revolutionaries, nearly hidden amidst images of birds and shadows, cities made of light and the skeletons of plants. They’re the only things in the book that feel solid. Everything else seems insubstantial, ‘a circus of souls’, saints and demons haunted by regret.

Alberto García-Alix never walked away. But he is not a victim of his past, nor is he trying to hang onto it as a trophy. He’s in it for the distance, not trapped, but watching intently, sadly, from just outside the frame, clicking the shutter as the energy of a past life slowly dissipates.

Alberto García Alix

MEP + AC / E + MCE + RM

Dr Eugenie Shinkle is a Reader in Photography at the University of Westminster

(All rights reserved. Text @ ASX. Images @ Alberto García-Alix.)