The vast majority of this material exists in a format without physicality. These ‘documents’ that the artist collects are in effect, de-materialised. They exist in a capacity of their non-physicality. It is an archival practice of collecting where the previous mode of acquisition is lost for that of an imagined meta-collection – a collection that, through the digital, becomes a post-collection of non-physical imagery to be used further than that of its original, private intent.

As the dusty shoeboxes that once held our private collections of photographs are replaced by public online forums, open to all, artists are able to mine a wealth of new (immaterial) material. Collector, photography dealer and editor of American Suburb X, Brad Feuerhelm navigates through the new vernacular of the Internet.

Brad Feuerhelm, ASX Editor and Partner, September 2015

In a world where practical photographic application has taken a backseat to that of concept and with the rise of the unnameable quantity of imagery found on the Internet, artists have begun collating and redistributing a taxonomy of imagery culled from all corners of our global network. The rise in collecting these abundant images stems not only from their readiness, but also because of their appearance in public forums from their previously dormant positions in private holdings. In the torrent of imagery that collides with daily life via the Internet, photographic art practice has learnt that what we do not know about the practice of photography could just about fit inside the metaphorical Grand Canyon.

This collection does not exist in a physical format outside the hard drive until repurposed for exhibition or book making. It is the becoming of these documents that is truly inspirational. To take their ambiguous representation and make it into a concrete object is something wholly indebted to the rise of the digital.

Previous historiographies of the medium, from Beaumont Newhall through to recent writings by Marina Warner, have failed to grasp the practice of collecting by artists in terms of its dusty corners and unseen material potentials. Artists have and will continue to consume abundant imagery unseen before the days of Flickr, Instagram and other social medias, seeking out imagery that previously lay dormant in attics, private albums and mobile phones. With the rise of public forums dedicated to sharing this imagery, we have, as a society, unlocked the potential of creating new vernacular sensibilities and practice: ways of working digitally, with images that we perhaps used to find in shoeboxes or family albums, but have been shifted from the private to the public to be consumed, collected, and redistributed into new collections and new practice.

This marauding effect of dislocating imagery from the source of intention has provided a wellspring of potential appropriation, which finds the artist acting as an oracle for which the images may be redesigned into a completely new narrative. These narratives, often woven together in a fragmentary cinematic discourse, allow the artist to use their collection in a way that was potentially unintended when they begin to stitch images together. To find the sources of such material, the artist must act as though each image were to be part of a collective body of work, ephemeral and reconditioned for use at a later date.

Notably, archival imagery has been used since the 1960s to drive towards conceptual practice. This collecting spirit existed before, but never without physicality until the rise of the ‘connectable momentary’ via the Internet. These fragments of narrative, when repurposed, often find a register in the audience and artist’s psyche that presents something of an uncanny disposition through the use of images of the ‘alien other’. When fed through a new public platform, the amateur or hidden private photograph brings insight into a unfamiliar terrain of people’s lives, previously unknown to the viewer, creating an investigation into a fragmentary discourse with lives that may feel uncannily familiar or alien.

This notion of representation also considers what we may relate to in regards to the hive mind. The hive mind – a collective understanding of imagery – is important for the use of such material. It dictates that although the source of content may have had a previous intention, within this paradigm the artist repurposes our collective reading of such images. The hive mind, akin to that of bees sharing their toil within the hive, points at a more universal understanding of images. The reading of the photographic as inherent memory, when reshaped into a dialogue with another intention completely distinct from the source of its making, presents a challenge. The original personal meaning or representation of the image becomes a secondary feature. This collecting, with its magpie like charm, has set the artist within course to distribute a new understanding of the taxonomy of photographic language in which the base language is stripped away. The artist/collector seeks to share his/her findings with the world, but in a new form. Within this, we may ascribe significant new meaning to the contextualisation of the image, but also to the practice of artistry that invokes it.

@ Lotte Reinmann from ‘Jaunt’

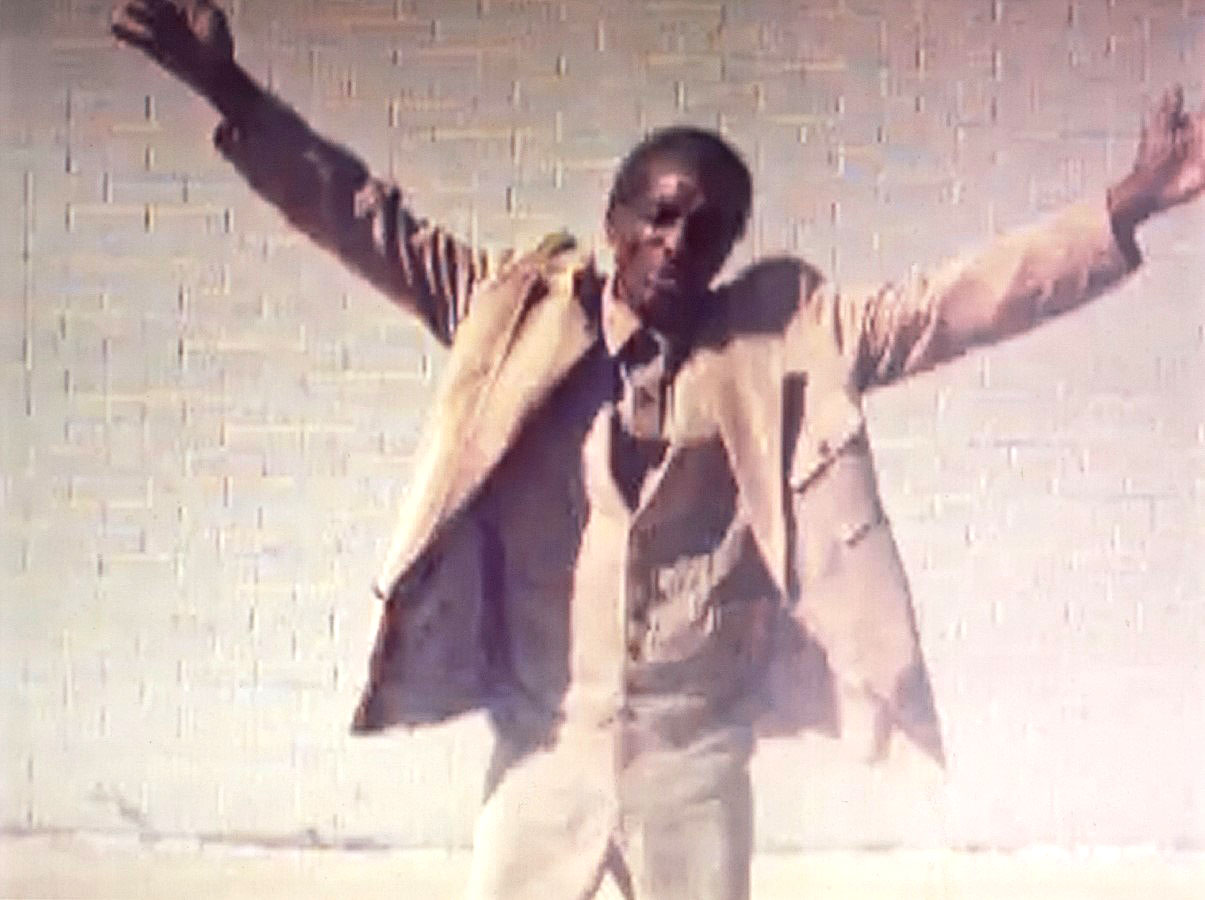

@ Doug Rickard from ‘N.A.’

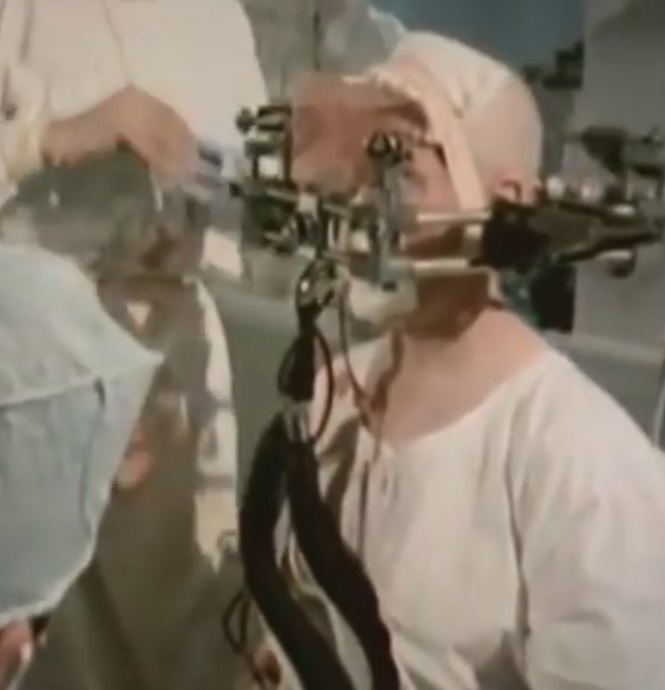

@ Lotte Reinmann from ‘Jaunt’

@ Doug Rickard from ‘N.A.’

It will be up to the artist and perhaps institutions to begin paying more attention to the formats in which we may collect this information in a non-physical way. We will have to consider how to store imagery, with its problematic shift in technology, and the backing up of back-ups of imagery made when these technologies go out of date.

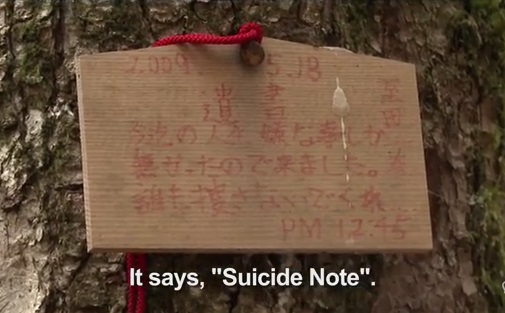

There are many core examples of artists collecting images for their work. Doug Rickard’s N.A. (National Anthem) is a sociological cinematic distillation of fragmentary moments, taken from unseen histories/footage of American society uploaded to YouTube. The videos are by and large from anonymous sources, made by people looking to distribute tiny glimpses of information that are usually personal, or carry with them a platform for which the democracy of the image/video is given reach to a wider audience. Here, there is a call for the viewer to look at the lives or messages of the person uploading for the gain of ideas or subjective distribution of information.

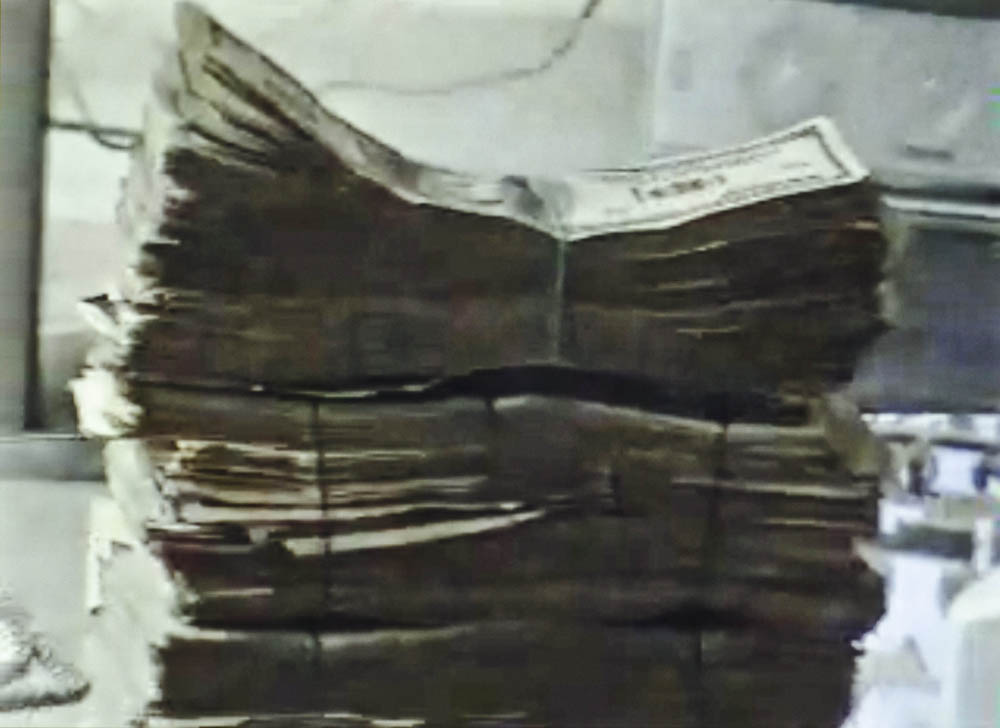

The videos Rickard collects are condensed down to a single frame from mobile phone footage and, through this process, become purposefully ephemeral. From the original codex of film to that of a single photographic remnant, they are re-contextualised into an editorial format that references the technological. The work is also symptomatic of the age we live in with America’s deteriorating system of racial injustice, larger issues of economic middle class displacement and the widening chasm between rich and poor. The images are collated and subsequently rendered into a ghostly and disturbing sequence of material, illuminated by fleeting presence and uncomfortable grimaces. Rickard, in collecting footage in this manner spends a large amount of time appropriating material and rendering the images into large amounts of metadata storage, which he sifts through ceaselessly to find material that speaks to a broader social concern. In doing so, he considers his job between that of the collector, artist and editor.

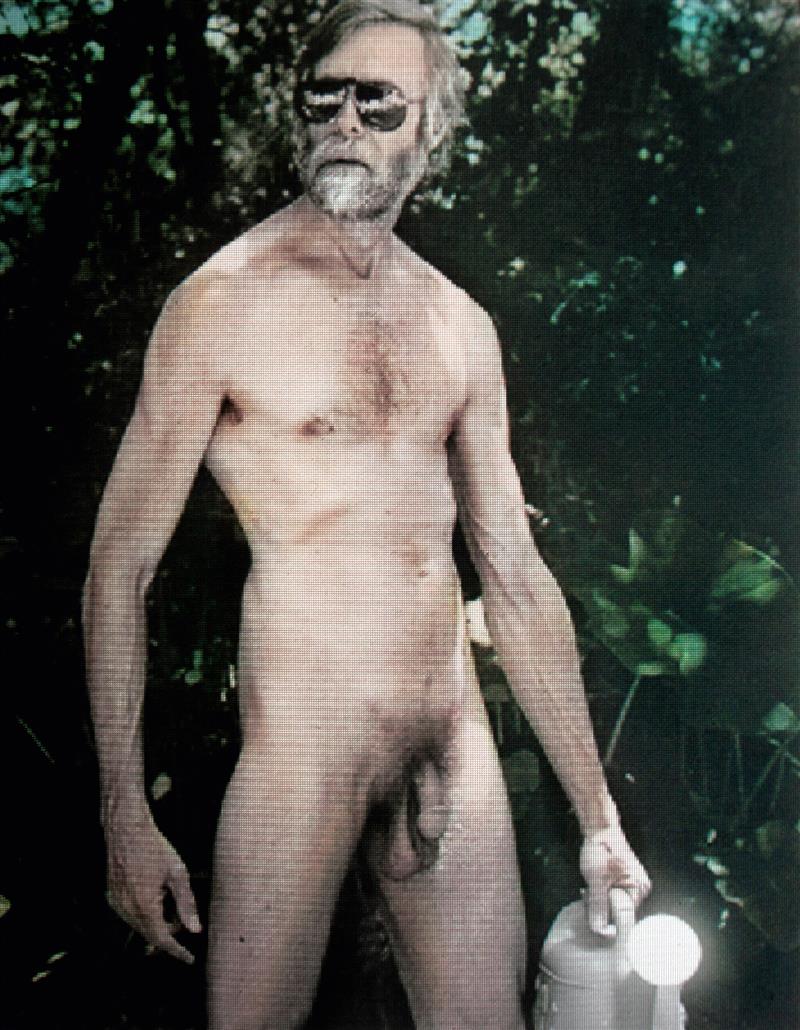

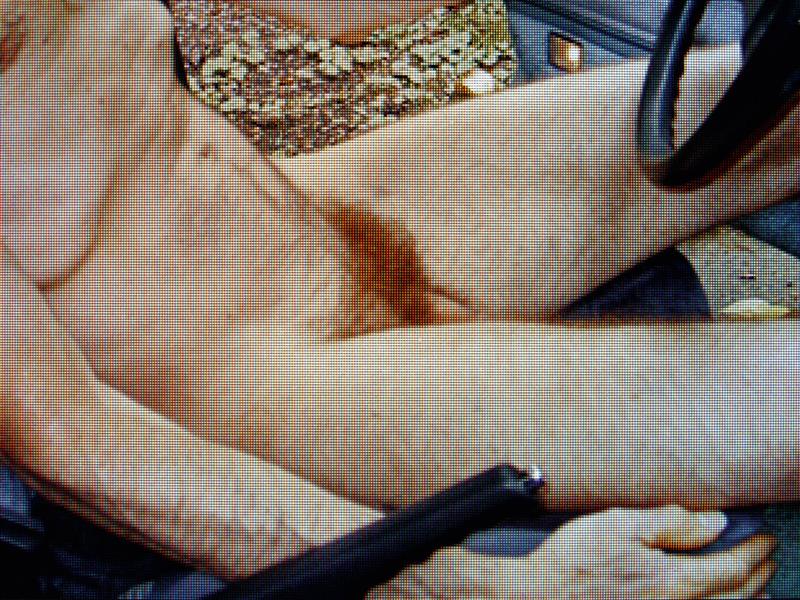

Image collecting enabled by technology is also vastly present in Lotte Reimann’s body of work and book Jaunt. Reimann, a German working in both Germany and the Netherlands, has woven together a completely fictitious narrative from fragments of imagery she has found of a couple on one of the vast amounts of photography sharing sites where couples upload their images for the consumption of a large audience. The images, when decontextualised and resequenced via the artist’s eye (not hand), begin to reinvent a story: a tall tale of two lovers traversing across America in a sexual escapade of the great American road trip.

By fragmenting the images, blowing them up and rephotographing them on her computer screen, Reimann presents a new context in which the narrative of the couple’s trip becomes something existential, obtuse, and highly charged. The smoke from the tires of a classic American automobile mingles with the nostalgic interiors of American hotel rooms. We have fashioned a hive understanding of this story. Though its particulars are completely personal to the main stars of the story, we collectively understand the environment and idea of the road trip through countless cinematic moments we recall from our own memories. Reimann’s work points at subconscious desires where age, abandon, and experience lead the viewer down the rabbit hole of a psychological guessing game, where the characters feel underdeveloped and the storyboard skewed and uncanny. These fragments often present a space in which the gaps between images – the unseen – present a methodology in which the viewer must make connections by themselves. Often these connections are short-circuited by the gap, creating a completely new subjective context.

As the digital age continues to sprawl along our collective use of the medium of photography, there will be less and less physical photographic objects for society to hold on to. Though there will be more and more amateur images created by mobile phones, film, and social media, we will lose the potential to understand this vernacular collecting base and its materialism in physical terms. It will be up to the artist and perhaps institutions to begin paying more attention to the formats in which we may collect this information in a non-physical way.

We will have to consider how to store imagery, with its problematic shift in technology, and the backing up of back-ups of imagery made when these technologies go out of date. It is interesting then that artists themselves have turned to this practice, reformatting our photographic histories for that of their collecting. To collect images which exist only in ether is to pay attention to the true meaning of photographic representation, the truth of which has and always will be subjective and fallible.

Little Big Man Gallery has announced Doug Rickard’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, opening on 9/19. It will debut the artist’s latest body of work titled N.A. Rickard’s new photography and video work continues to explore the darker side of urban America and highlights issues of economic disparity, ever-present surveillance and tendencies toward publicity via social media. The show will also mark the gallery’s grand opening in its new, larger exhibition space.

EXPLORE ALL DOUG RICKARD ON ASX

(All rights reserved. Text @ Brad Feuerhelm and Unseen. All images @ the artists.)