Romance is inescapable; the L.A. river is maybe the most romantic strip of concrete in the world, the light in the window of a Todd Hido exterior is romantic, just the name “Dennis Hopper” is romantic; romance is inherent to the image.

By Owen Campbell, ASX, July 2015

Both Sides of Sunset: Photographing Los Angeles is a study of Los Angeles, yes, but also a crash course in the last half-century of photography; every style, theme, and problem of photography in the past sixty years comes out in these photographs of Los Angeles, which seems to offer the medium greater richness than any other city on earth. A follow up to 2005’s Looking at Los Angeles, Both Sides of Sunset again features the work John Baldessari, Julius Schulman, Robert Adams, John Divola, Florian Maier-Aichen, and Stephen Shore, to name only a few. Yet it’s so large, nearly 300 pages, and so diverse in reach and style that even the biggest names in photography are merely blended into sprawling collection of images.

Both Sides of Sunset shows the roads, the homes, the cars, the beach, the mountains, the riots in Watts and at the beach, the immigrants walking in the brown hillside grass to the side of the highway, advertisements from the couple post-war decades when having one’s life flooded with advertisements was still a novel experience, heavy industry, red sky, smoke, fire, rain. The images typically come grouped in sets, black and white architectural photos followed by color shots of car culture, followed by landscape followed by street photography, but the categories and transitions are unannounced. The categories blend into each other and across decades as the photographs shuffle through time and space, moving from downtown fifty years ago to the outskirts in the nineteen-eighties and panoramic helicopter shots from this decade.

It’s a rich book, too large and too diverse to neatly summarize, but it has more soul than just a “survey” of Los Angeles photography. The jacket copy calls Both Sides of Sunset “unromantic” – which isn’t exactly true – there’s certainly a romance to Skid Row, to Bill Ray’s images of Hell’s Angels. Romance is inescapable; the L.A. river is maybe the most romantic strip of concrete in the world, the light in the window of a Todd Hido exterior is romantic, just the name “dennis hopper” is romantic; romance is inherent to the image, and while it shares a soft border with cliché, romance is not a bad thing

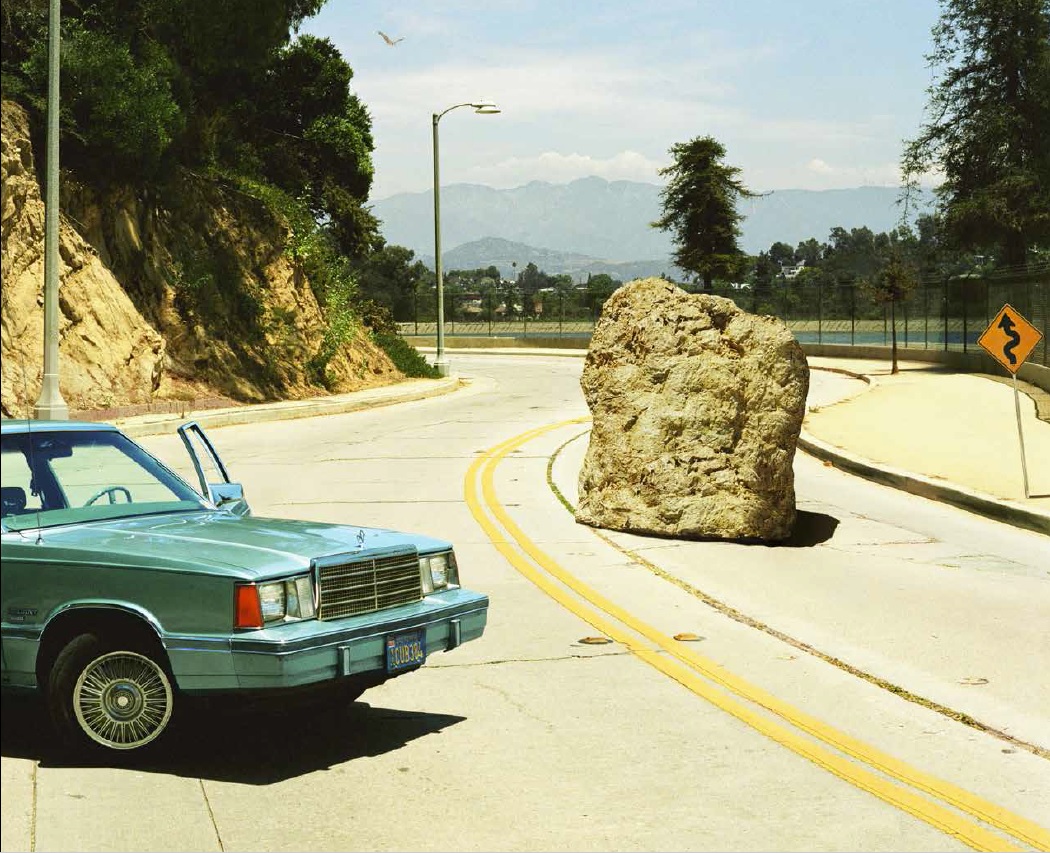

Among the best in Sunset are two photos by native Angeleno Alex Prager. In 1:18 p.m. Silver Lake Drive, 2012 a perfectly aged 90’s era Chrysler is stopped diagonally across one lane of a winding road at the bottom of a hill, the door is open but there is no driver to be seen. In the other lane is a massive boulder, at rest. In the background is a thin strip of the Silver Lake Reservoir, beyond that are the mountains and above the mountains a bird. The darkness of the greenery around the road forms a perimeter around the washed-out blues of the mountains and sky, the beige-white road and pale yellow double line winding in its middle. The seafoam-turquoise-teal of the foregrounded Chrysler Plymouth, and the contrast of this most vibrant color field of color set against the darkest area, the shadow underneath the car, creates the focal point of the composition and underscores the small mystery of the missing driver. The boulder fell. The Chrysler Plymouth swerved and stopped. The left border of the image crops the rear of the Chrysler, you can only see the hood and through the windshield to the steering wheel and out the open driver’s side door. The driver got out; where did she go? The image is a silent, slightly disquieting story of the near past

Alex Prager, Julie, 2007

Dennis Hopper, Los Angeles (Wallace Berman on Motorcycle), 1964

Alex Prager, 1:18 p.m. Silverlake Drive, 2012

As Hollywood also exports, as normative, the appearance of Los Angeles, disguised or not, the idealized particularities of other cities are constructed from those of Los Angeles.

Prager’s Julie also creates the same impression, one image part of an incomplete story, but with even more of a film-still effect. It shows a woman, presumably Julie, shot from behind, in a seemingly precarious situation, as it seems like she’s trying to descend a rough, hay-strewn hillside. Her hair, her heels and her skirt wouldn’t be out of the place in the early sixties. The sky and her outfit have a familiar, classic Hollywood Technicolor hue, and then there’s the ominous bird, all of which combines to make Julie seem like a distressed Hitchcock heroine.

Among the other highlights are Julius Shulman’s architectural photos. A pair of drive-in theatres in Terrace Theatre (Los Angeles, Calif.) from 1941 and Pan-Pacific Theatre (Los Angeles, Calif) from 1942 are shot in high-contrast black and white, both cool and stark, their white lights look seared into in the sky. Also, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Building (1965), is seen through Shulman’s lens as sharp and bright, throwing light out from between the levels of it’s razor-like shell. The power to move water made Los Angeles more so than any other large city; it’s appropriate that the real institution looks just as weighty and foreboding as building it might in a modernist retelling of Chinatown.

As the capital of America’s entertainment industry as well a geographically diverse area in topography and built environments, it’s a foregone conclusion that Los Angeles will “play” other, real places, or, just as commonly, indistinct, nameless and generic places. Dayna Tortorici writes about how even architectural monuments, like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House are used as interchangeable props in for various stylized genre-pieces, “What’s made them interchangeable is the cultural dominance of Hollywood. Hollywood has denied Los Angeles the ability to be particular.” The obverse truth of this insight is that as Hollywood also exports, as normative, the appearance of Los Angeles, disguised or not, the idealized particularities of other cities are constructed from those of Los Angeles. Consequently, what’s mistaken as authentic vernacular American imagery is really the well-budgeted and focus-grouped image of suburban Los Angeles. Just one appeal of Both Sides of Sunset is that it circumvents pat depictions of the city most typically overexposed and shot in soft focus in order to present it as unique and unidealized, but more than anything unexportable.

Both Sides of Sunset: Photographing Los Angeles

ISBN 9781938922732

Owen Campbell is an an artist and writer from Wilkinsburg, PA.

FOLLOW on Twitter @OwynnKampbell

Connect to the ASX universe. Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

(All rights reserved. Images @ the artists and the publisher.)