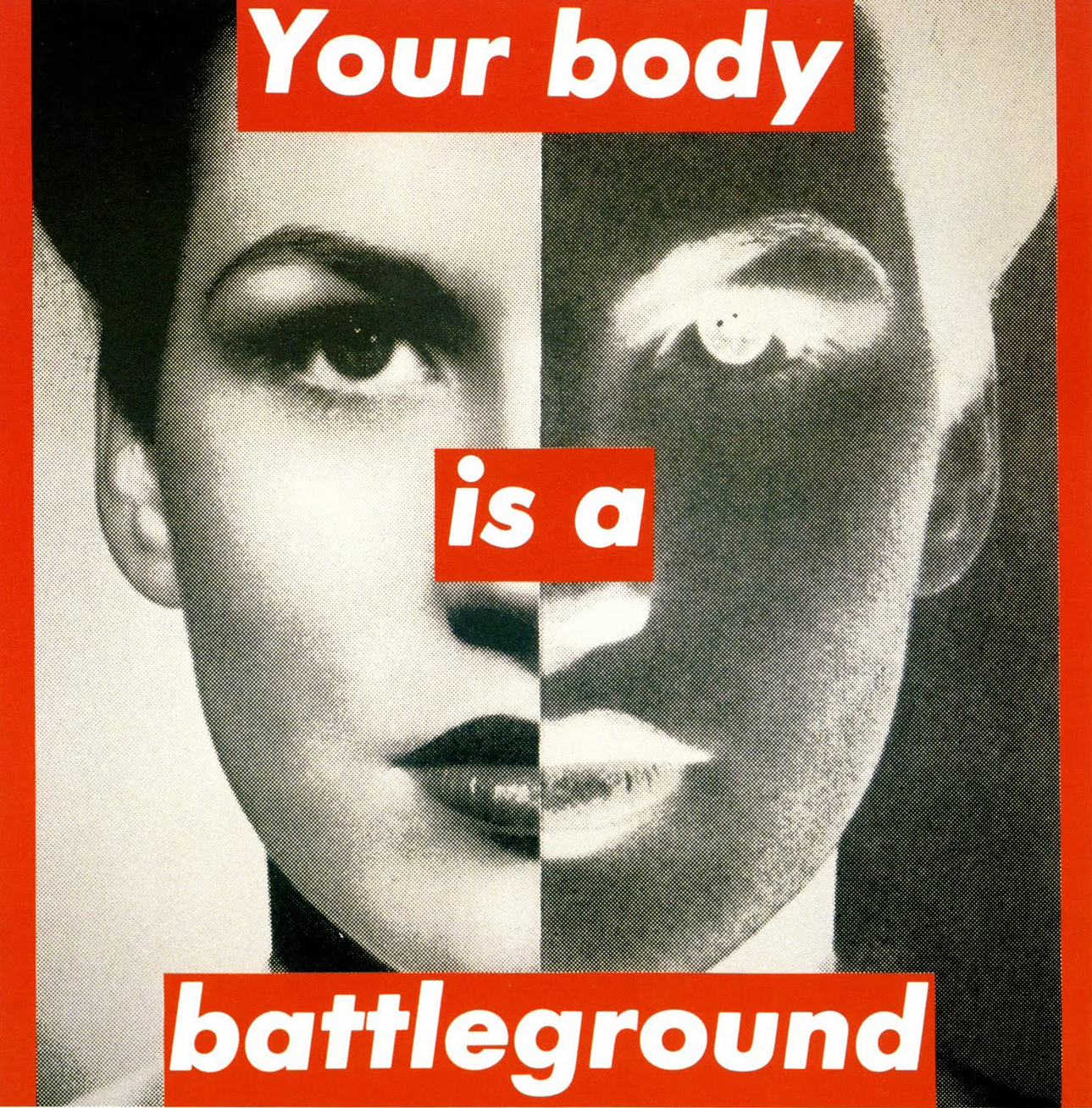

Barbara Kruger

Untitled (Your body is a battleground)

1989

Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery New York

“I hate to get to you on these words, but I wouldn’t call it an agenda-but I would say that I am interested in sort of, in not just displacing and questioning stereotypes.”

Barbara Kruger Interview, excerpt from Critical Inquiry 17, Winter 1991

MITCHELL: Is part of the agenda of your images, then, to re-embody, or to restore the body to these stereotypes?

KRUGER: Yeah-and I hate to get to you on these words, but I wouldn’t call it an agenda-but I would say that I am interested in sort of, in not just displacing and questioning stereotypes-of course I’m interested in that – but I also think that stereotype is a very powerful form and that stereotype sort of lives and grows off of that which was true, but since the body is absent, it can no longer be proven. It becomes a trace which cannot be removed. Stereotype functions like a stain. It becomes a memory of the body on a certain level, and it’s very problematic. But I think that when we “smash” those stereotypes, we have to make sure and think hard about what we’re replacing them with and if they should be replaced.

MITCHELL: If stereotypes are stains, what is the bleach?

KRUGER: Well, I wouldn’t say that there is a recipe, and I wouldn’t say “bleach.” Bleach is something which is so encoded in this racist culture that the notion of whitening as an antidote is something that should be avoided.

MITCHELL: So you just want to stop with the stain.

KRUGER: I don’t want to get things whiter. If anything, I would hope when I say that basically to create new spectators with new meanings, I would hope to be speaking for spectators who are women, and hopefully colleagues of mine who are spectators and people of color. Now that doesn’t mean that women and people of color can’t create horrendous stereotypes also. Of course they can. But hopefully one who has had one’s spirit tread upon can remember not to tread upon the spirit of others.

MITCHELL: Most of your work with the problem of difference has focused on gender. Are you interested in or working on problems with ethnicity, since that certainly involves a whole other problematic of embodiment?

KRUGER: Well, I think about that all the time. I think about it in terms of race, and culture. I think about it when I teach. I think about it in a series of posters that I do and of projects for public spaces, but I also-unlike a number of artists-feel very uncomfortable and do not want to speak for another. I basically feel that now is the time for people of color to do work which represents their experience, and I support that, and have written about that work as a writer, but do not want to speak for others. I basically feel that right now people of color can do a better job of representing themselves than white people can of representing them. It’s about time.

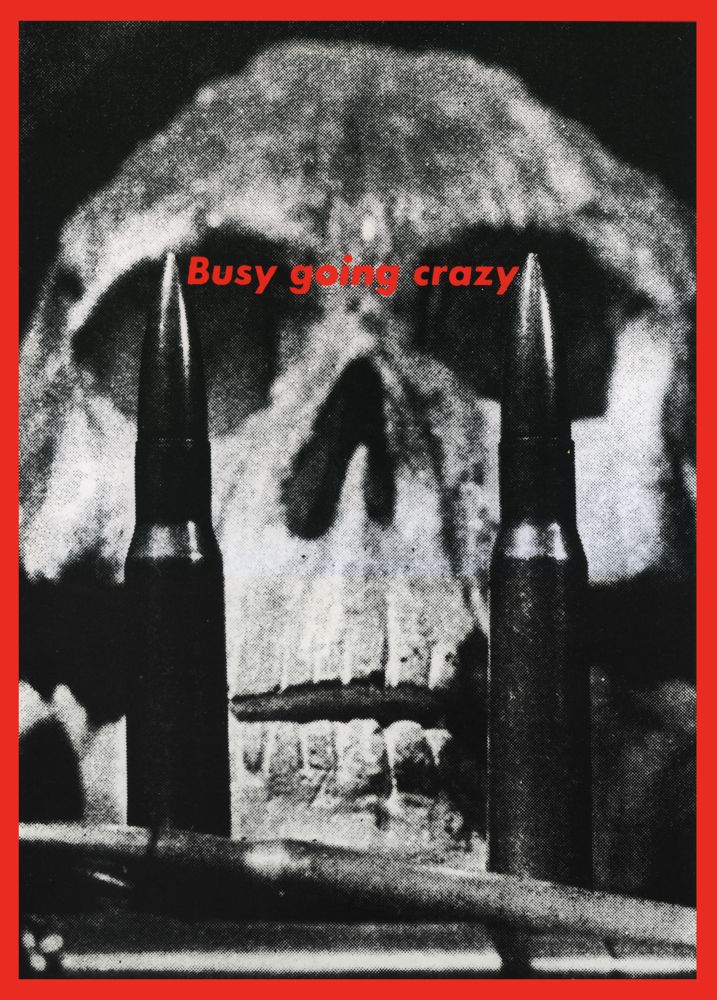

Barbara Kruger

Untitled (Busy going crazy)

1989

Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery New York

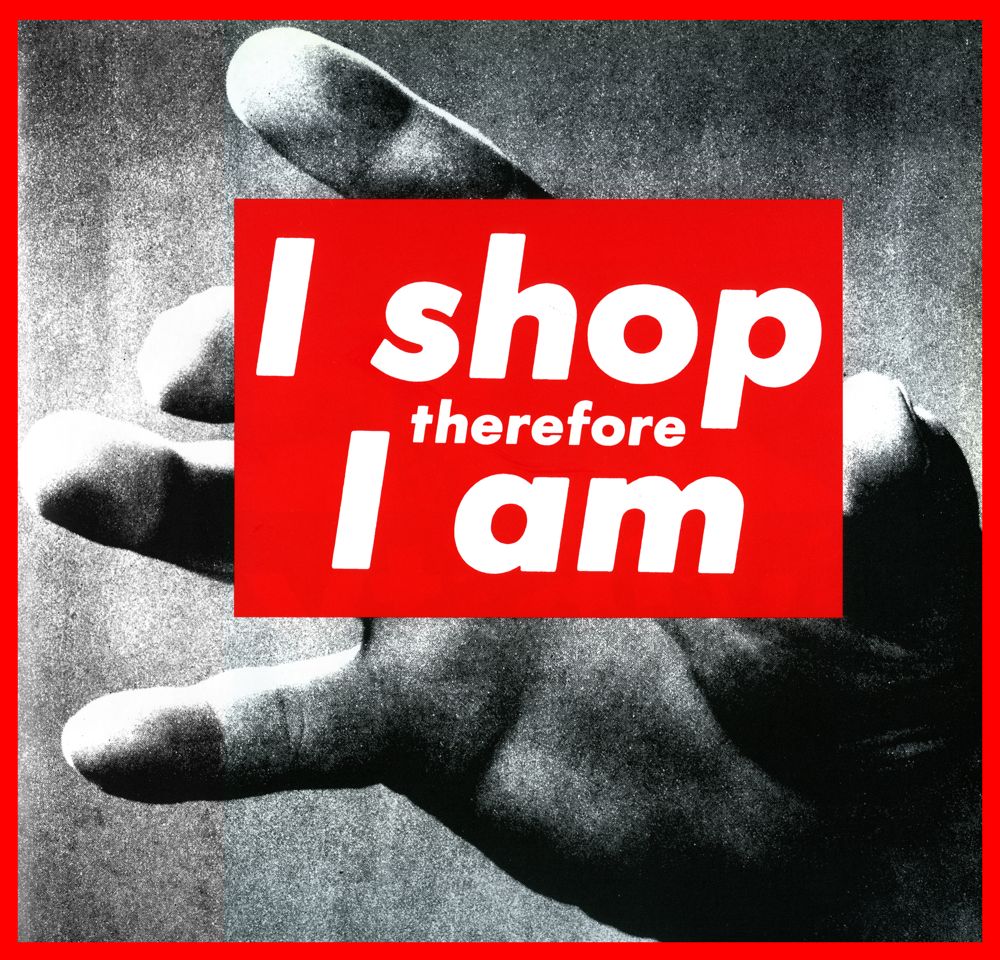

Barbara Kruger

Untitled (I shop therefore I am)

111″ by 113″

photographic silkscreen/vinyl

1987

Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery New York

“I’m not saying that something should be unreadable. I’m saying that it should be readable, but it should suggest different meanings or that it should give a meaning.”

MITCHELL: Let me just take one further step with the problem of word and image, and try to tie it back into the issue of public art. I’m interested in the combining of words and images in the art of publicity and in traditional public art, the old-fashioned monument.

Let me just give you a little background on what I’m thinking here. The traditional public art, say, of the nineteenth century, is supposed to have been universally readable, or at least

it’s often invoked that way, as something that the whole public could relate to. Everybody knows what the Statue of Liberty was supposed to mean, what it “says.” When modern works of public

art are criticized, they’re often characterized as “unreadable” in contrast to traditional works which were supposedly universally popular. The modernist monument seems to be a kind of private

symbol which has been inserted into the public space, as I think you said, the garnish next to the roast beef. So it looks as if modernism kept the monument in terms of its scale, and egotism, and its placement in a public site, but it eliminated the public access to meaning.

This is all a kind of complicated preamble to asking whether it might be possible that word-image composite work-especially coming out of the sphere of advertising and commercial publicity might make possible a new kind of public art. I know this is to bring you back to something you said you’re not terribly in love with, or you have some problem with, the whole issue of public art.

But, does this question make sense to you?

KRUGER: Yeah, I think that there is an accessibility to pictures and words that we have learned to read very fluently through advertising and through the technological development of photography and film and video. Obviously. But that’s not the same as really making meanings, because film, and, well, television, really, and advertising-even though it wants to do the opposite-let’s just talk about television-it’s basically not about making meaning. It’s about dissolving meaning. To reach out and touch a very relaxed, numbed-out, vegged-out viewer. Although we are always hearing about access to information, more cable stations than ever, . . . . But it’s not about the specificity of information, about notions of history, about how life was lived, or even how it’s lived now. It’s about another kind of space. It’s about, as Baudrillard has said, “the space of fascination,” rather than the space of reading. “Fascinating” in the way that Barthes says that stupidity is fascinating. It’s this sort of incredible moment which sort of rivets us through its constancy, through its unreadability because it’s not made to be read or seen, or really it’s made to be seen but not watched. I think that we can use the fluency of that form and its ability to ingratiate, but perhaps also try to create meanings, too. Not just re-create the spectacle formally, but to take the formalities of the spectacle and put some meaning into it. Not just make a statement about the dispersion of meaning, but make it meaningful.

MITCHELL: That’s what I was hoping you were going to say. My next question was whether you feel there’s still some place for the unreadable image or object (which I’ve always thought of as one of the modernist canons: the idea that an image has mystery and aura and can’t be deciphered).

KRUGER: But that’s not what I’m saying. That is not what I’m saying.

MITCHELL: You’re speaking of another kind of unreadability.

KRUGER: I’m not saying that something should be unreadable. I’m saying that it should be readable, but it should suggest different meanings or that it should give a meaning. I’m saying that what we have now is about meaninglessness, through its familiarity, accessibility, not through its obscurity. Whereas modernism, or what I take it to be (you’ve used the word), was meaningless to people because of its inaccessibility. What the media have done today is make a thing meaningless through its accessibility. And what I’m interested in is taking that accessibility and making meaning. I’m interested in dealing with complexity, yes. But not necessarily to the end of any romance with the obscure.

MITCHELL: There was one other question I wanted to ask you, and that’s about interviews. The old idea about artists was that they weren’t supposed to give interviews. The work was supposed to speak for itself. How do you feel about interviews?

KRUGER: I think that the work does speak for itself to some degree absolutely. But I also feel that we’re living in a time when an artist does not have to be interpreted by others. Artists can “have” words. So it’s not like I think I’m going to blow my cover if I open my mouth.

MITCHELL: Well, you certainly haven’t blown your cover today.

(All rights reserved. Text @ W. J. T. Mitchell. Images @ Barbara Kruger.)