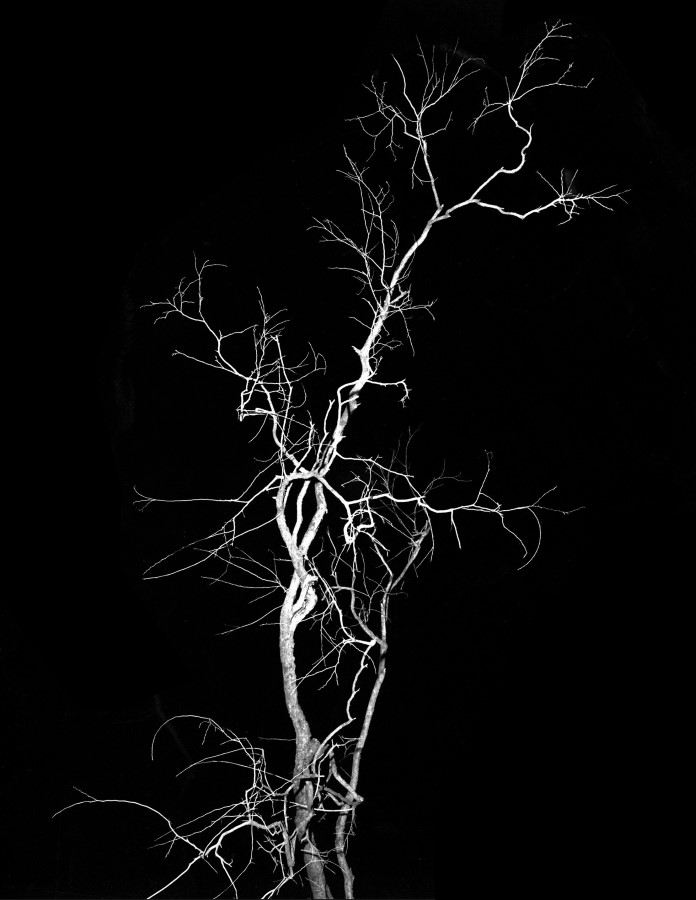

The earth arcing up in anger at the sky – is the only part of a lightning strike that is visible to the human eye.

By Eugenie Shinkle, ASX, February 2015

Lightning – at least the part of it that we can see – doesn’t come from the sky. Invisible fingers of negatively-charged particles reach down, tentatively, from the clouds, looking for a place to land. As they approach a target on the ground, a bolt of positively-charged particles rushes up to meet them. This reversal of the apparent order of things – the earth arcing up in anger at the sky – is the only part of a lightning strike that is visible to the human eye.

Up until the end of the sixteenth century, Michel Foucault writes, humans knew the world by means of representation. The relationship between things and their place in the labyrinthine web of knowledge was given by qualities like proximity and emulation, analogy and sympathy. Thus the walnut’s use as a treatment for wounds to the human head was legible in its appearance, the nut’s hard shell and wrinkled surface emulating the skull and the brain within. The universe, Foucault attests, ‘was folded in upon itself: the earth echoing the sky, faces seeing themselves reflected in the stars, and plants holding within their stems the secrets that were of use to man.’ Everything was connected.

Lightning Tree puts this alchemical process to work on the microcosm of Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs’ own archive. Produced to mark the occasion of the pair’s recent solo exhibition The One-Eyed Thief, held at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, Lightning Tree draws together images from a number of recent projects. It’s more of a postscript than a catalogue, and also includes photographs that weren’t part of the exhibition.

The Swiss duo are known for their playful conceptual work, but Lightning Tree explores the more arcane twists and turns of their collective imagination. Here, they cast their spell over the logic of the series, chasing the fugitive elements of the relationship between world and eye and camera, between image and afterimage and afterthought, between knowledge and necromancy.

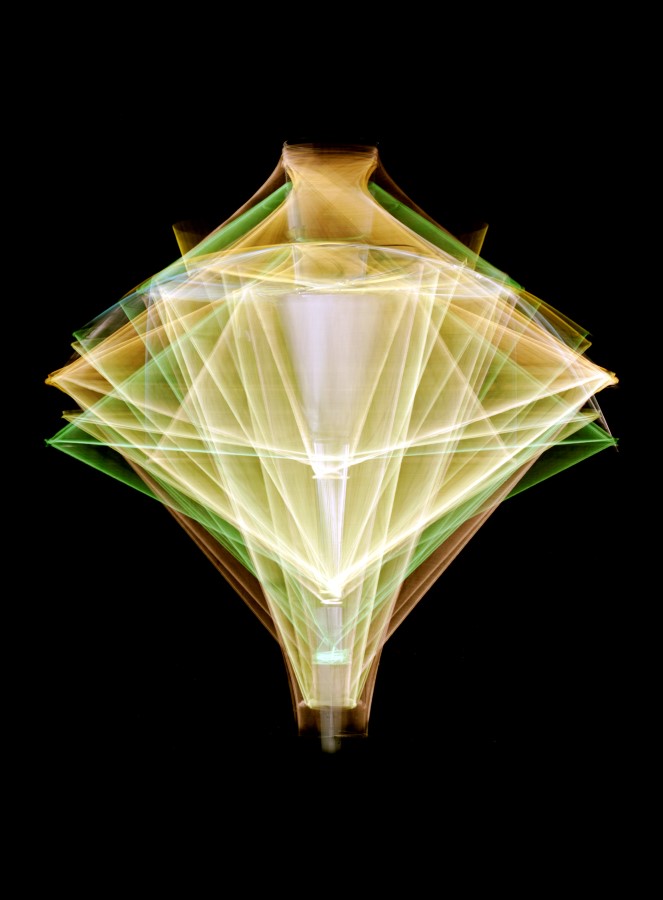

The Swiss duo are known for their playful conceptual work, but Lightning Tree explores the more arcane twists and turns of their collective imagination. Here, they cast their spell over the logic of the series, chasing the fugitive elements of the relationship between world and eye and camera, between image and afterimage and afterthought, between knowledge and necromancy. Here, the hinge between one photograph and the next is forged out of the confrontation of resemblances and the consonance of forms. And this random walk through Onorato and Krebs’ optical unconscious gives us a world as it appears, enchanted, before the calculating eye does its sums and casts perception in stone.

In this world, the tree is the organic matrix from which everything springs: empty branches flash-struck and ragged against the darkness, like fingers of lightning. The intricate venous networks cascading out from a preserved human heart, standing upright in a glass vitrine, looking like it’s screaming. A cyclopean foetus, reposing comfortably in a jar of formaldehyde on a sunny windowsill. A column of light spinning in a forest, and the puddled, amoebic patterns in a slab of quarried marble. One image reaches out to the next, wide-eyed in the dark.

Kevin Moore’s essay takes up this web of coincidence, and runs with it through the garden of organic forms that inspired the Modernist imagination: Karl Blossfeldt’s monumental images of plants, Alexander Rodchenko’s tall, naked pines, and the biotechnical fantasies of László Moholy-Nagy. The rational principles that drove technology and industry and the modern way of life all had their genesis in the natural world. The organic was bound to the inorganic, the animate to the inanimate.

Lightning Tree imagines the way that photographic images might call out and answer to one another when we’re not looking. It traces the patterns of similitude, the ciphers on the face of the world, as they make their way through the guts of vision machines. The camera runs its gaze over the surface of things, gentle and insidious as fingers of lightning. It all begins and ends with a flash. Everything is connected.

Eugenie Shinkle is a Reader in Photography at the University of Westminster

(All rights reserved. Text @ Eugenie Shinkle. Images @ Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs.)