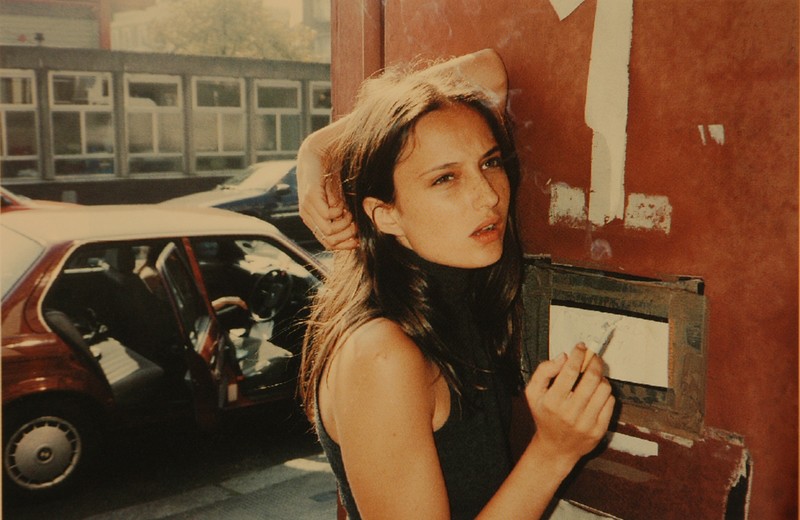

from Go-Sees, @ Juergen Teller

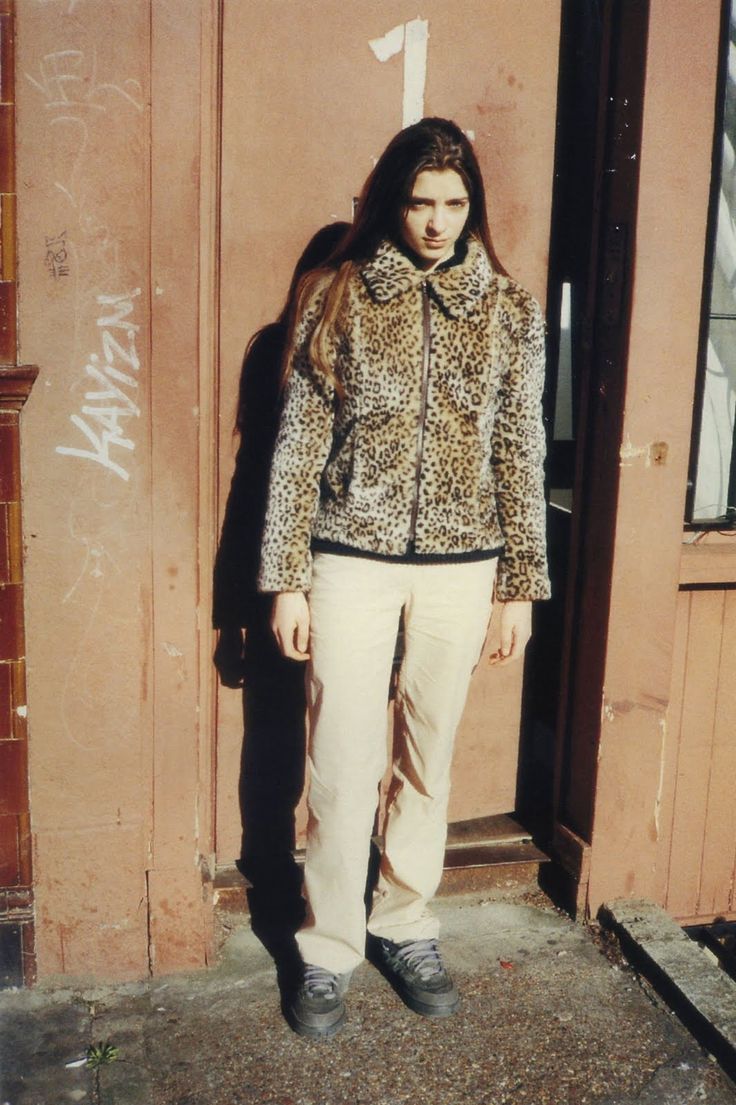

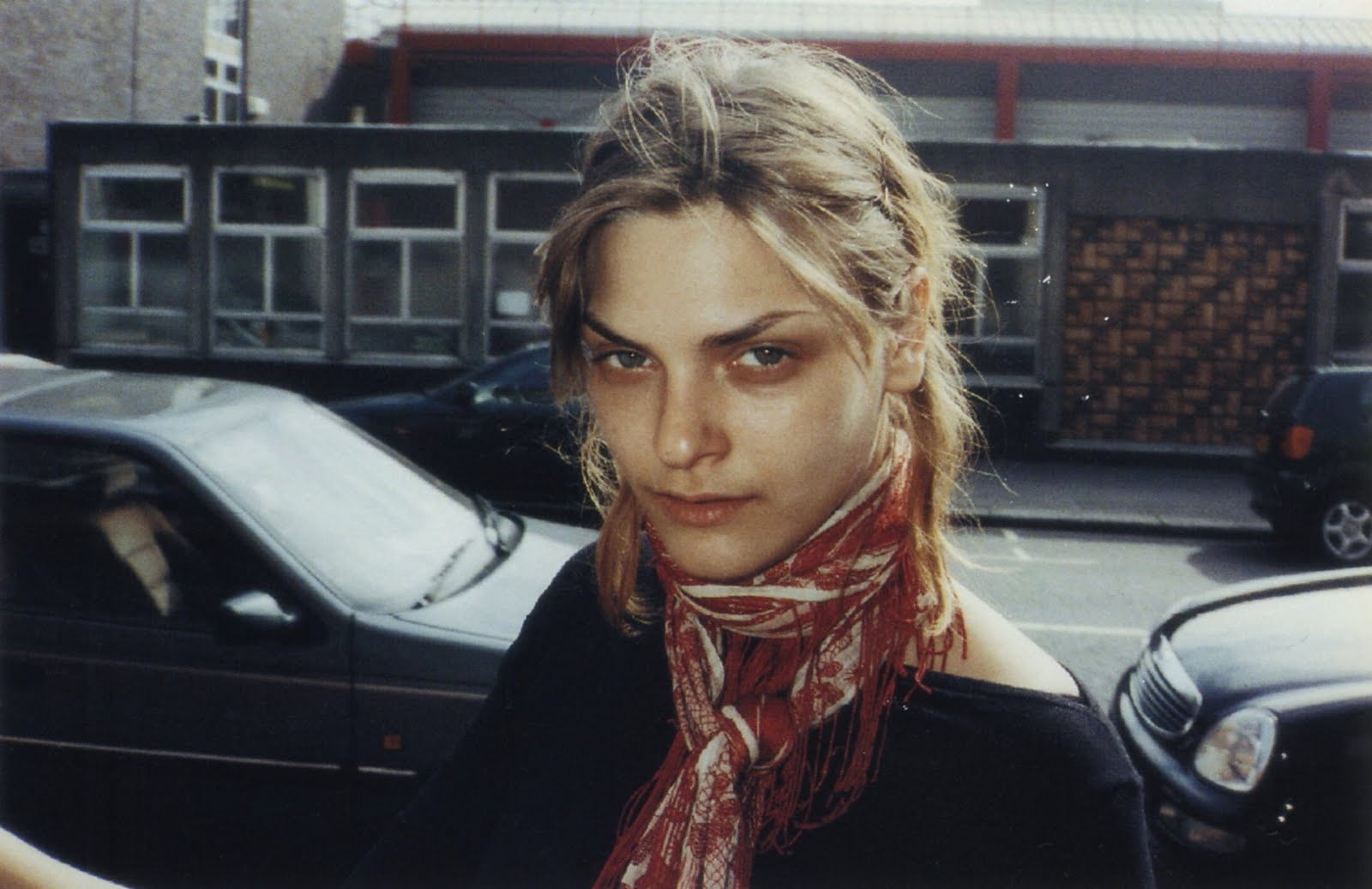

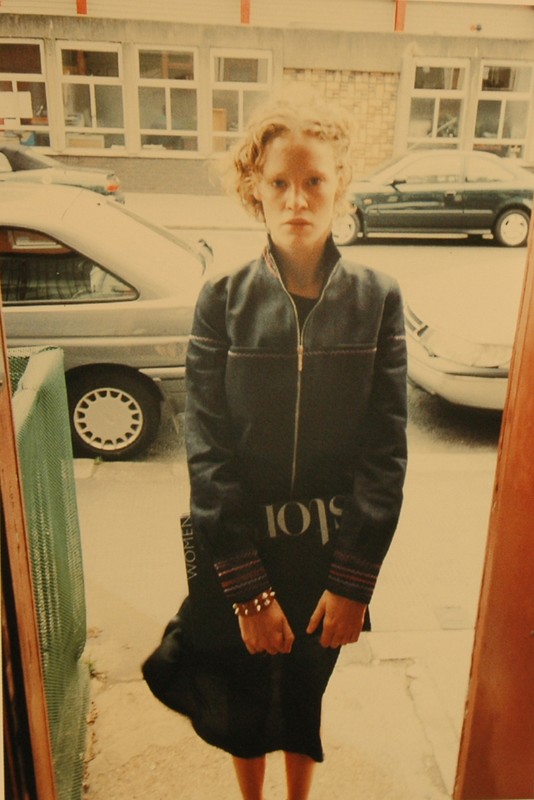

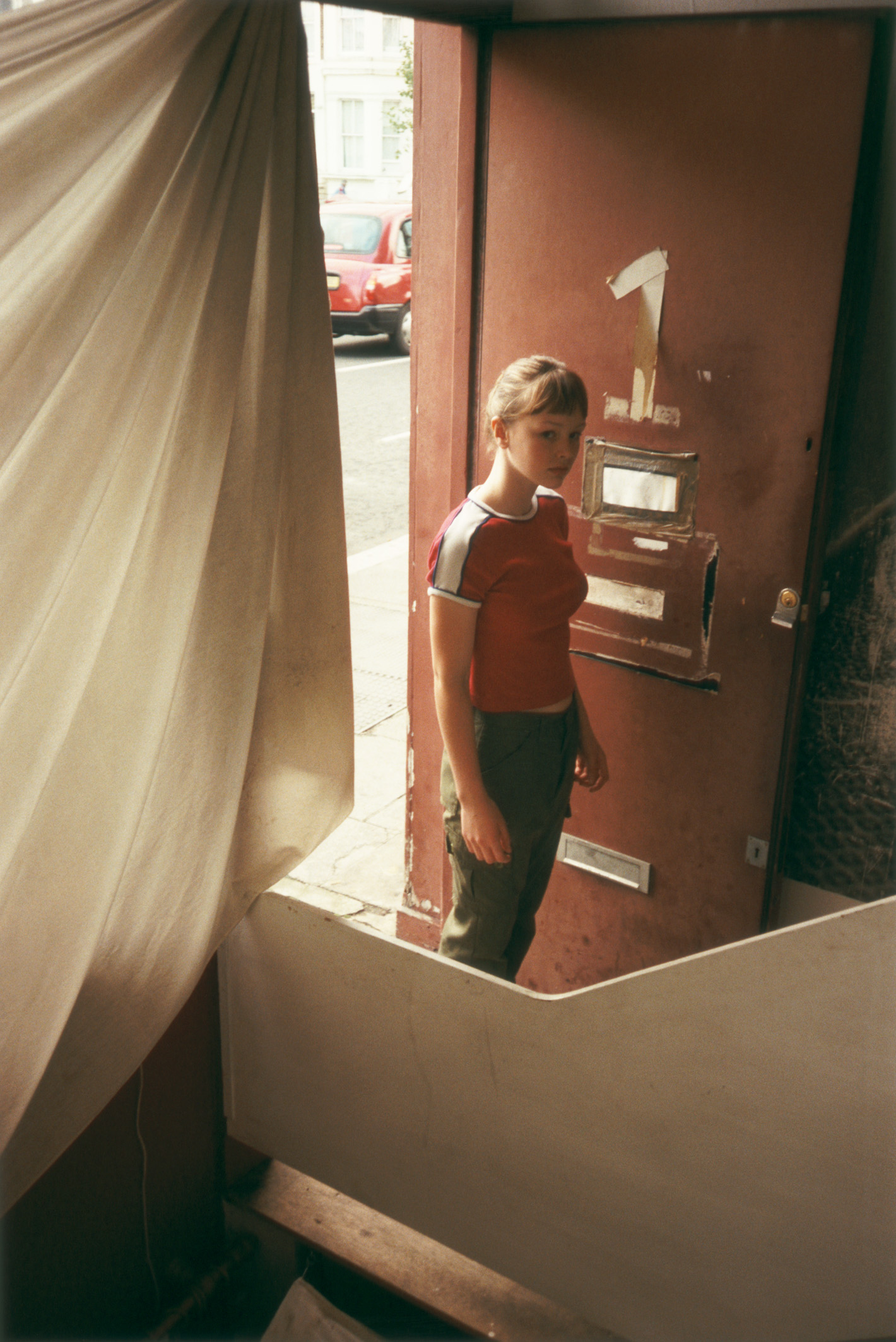

Made over a twelve-month period, Go-Sees is a collection of photographs that depict the hundreds of women and young girls who called at Teller’s studio for an informal meeting in the hope of securing the modeling contract that would lead to fame, fortune and a life of ‘glamour’.

By John Tozer, originally published in Contemporary Visual Arts, Issue 28, 2000

With the formulaic coterie of gaunt, pancaked and digitally manipulated young women pouting and leering at up from magazine covers, advertising hoardings and the glossy pages and soft porn that pass for women’s style journals, we have become accustomed to the long, lean arm of the modeling industry extending into our daily lives. Nevertheless, it is a surprise to find evidence in Juergen Teller’s Go-Sees of quite so many hopeful young women starving, painting and depilating themselves in pursuit of the sort of career that involved the commodification and consumption of their image by complete strangers.

Made over a twelve-month period, Go-Sees is a collection of photographs that depict the hundreds of women and young girls who called at Teller’s studio for an informal meeting in the hope of securing the modeling contract that would lead to fame, fortune and a life of ‘glamour’. As such, what Go-Sees offers us is page after page of shiny snapshot images of girls collected, like so many flattened flowers in an album, between vulgar gold cloth covers.

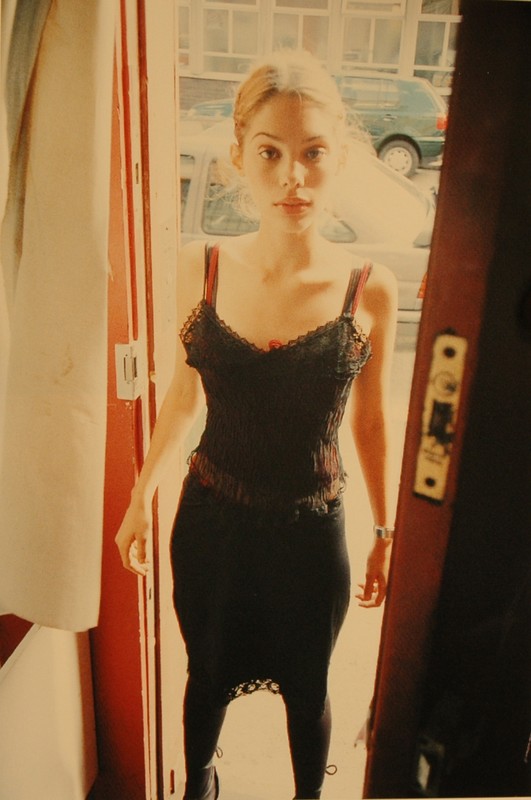

A ‘go-see’ is fashion industry slang for a would-be model who may or may not be worth engaging. The go-sees that Teller has photographed in the doorway to his studio since mid-1998 are not professionals but young women who have embraced the appearance and ideology of the world of fashion, and who decorate and deport themselves in a simulacrum of some form of ‘authentic’ model status. Ironically, and some could argue unhappily, the supermodels that these girls have attempted to emulate are themselves as far removed from any real notion of womanhood as Pot Noodle is from a square meal.

The girls appear not quite as models or even as ‘normal’ young people but as something somewhere in between. The glamour world’s form of idealized beauty, which some of the girls approximate more convincingly than others, is a fiction, an abstraction and a fantasy, and it is impossible to say who is most seduced by this absurd ideal – men, women, or the girls themselves. Clearly these girls wish to be beautiful, and to be recognized as being beautiful, but this beauty is itself little more than a construct that has evolved from an economy of production and consumption based less on aesthetic universals than on culturally overdetermined aspects of desire.

Though we are aware that the photographs belong to a real narrative that involved Teller and his visitors, the visual aspect of the girls – what we see when we look at them – are overwritten by the codes that govern our readings of a femininity mediated by the fashion industry. Teller’s photographs are not portraits in the sense that they seek to describe the individuals depicted, as the various Rebeccas, Giseles, Hannahs, Ninas, Naomis, Saskias, Zanettas, Jades, Charlottes, Saffrons and Juliettes all look the same – all conform to a limited notion of modelhood, all have the same look of rueful candour, slightly tainted by a vague awareness of the voyeuristic lechery of the camera lens.

What do these girls want? Indeed, what do we want from them? Rather than wondering why Vesna has no eyebrows, or how old Lynsey is, or whether Lauren has eaten anything in the last six months, we just assume – because of the endless repetition of vaguely pretty girls – that their images are no more related to any tangible, palpable reality than is the impossible bosom of Lara Croft. Besides, in truth we have no need to ask these questions, as we already know what the answers will be.

from Go-Sees, @ Juergen Teller

One could argue that in ‘taking’ these girls’ photographs Teller has acted with neither morality nor intellectual critique, for what he has effectively done is exploit his position as a fashionable photographer in order to amass a vast quantity of marketable images, with no obvious intention other than to share them with an unseen public at a later date.

Teller, while highlighting the production-line nature of an industry obsessed with appearances, must nonetheless admit to a degree of duplicity and culpability. On the one hand, his project is a valuable one, for it illustrates and articulates the unspoken strains of discontentment within modern young females – factors which drive hordes of them to seek recognition within a world that dictates abstract standards of beauty to an acquiescent culture. But on the other hand Teller is deeply implicated within this world, despite the quasi-art-status his works have achieved within an art industry that is as greedy for products as is the ‘low’ culture to which it used to be in opposition.

One could argue that in ‘taking’ these girls’ photographs Teller has acted with neither morality nor intellectual critique, for what he has effectively done is exploit his position as a fashionable photographer in order to amass a vast quantity of marketable images, with no obvious intention other than to share them with an unseen public at a later date. There is no accompanying statement of intent, and no recognition of the roles played by the young women who made Go-Sees possible; as such this tends to position Teller not so much as author of a body of work but rather as exploitative consumer of bodies.

Individually the images have little to recommend them other than the passing appeal of their subjects, so we have to see Go-Sees as a project in itself rather than as a collection of separate photographic works. The evident perfunctoriness with which the images were made, and their lack of obvious ‘photographic qualities, indicates that we should not waste our time searching for formal values such as colour or composition but simply enjoy the girls quickly, one after the other, as the book invites us to do.

If attempts to position Teller’s Go-Sees within existing recent histories of snapshot photography, the most – or perhaps the least – obvious comparison one could make is to Gillian Wearing’s Signs that say what you want them to say and not signs that say what someone else wants you to say. In this well-documented series Wearing gave white card and felt markers to anyone on the streets who cared to take them, inviting people to write whatever they wanted on the card. When they had finished she photographed them holding their messages. In a sense Wearing, like Teller, exploited the individuals as a resource; but unlike Teller’s subjects, Wearing’s have a voice. Teller’s go-sees are effectively rendered speechless inasmuch as the only language they are allowed already belongs to the world of fashion. In the real world they are reduced to little more than silent, consumable, coffee-table titillation.

One could also place Go-Sees within the ‘stolen’ Metro photographs of Luc Delahaye, the ‘street photography’ of Garry Winogrand, or the mercilessly non-judgmental studies of the British working classes by Martin Parr.

However, behind these works are a number of serious artistic projects, whereas Teller has admitted that, though it is important to him to create photographs that ‘leave your imagination free to think about what kind of life this person leads’, he also ‘enjoy[s] taking pictures of a girl in – and out of – clothes.’

The striking images Teller has made of personalities from the world of fashion, film and pop music have earned him a reputation as a popular and fashionably credible photographer. Despite this, though, the signature style for which he is known is paradoxically general and democratic, as his photographs share many qualities with the snapshot images produced by those of us who take photographs as a simple and economic way of recording events in our lives. For most camera owners photography is a means of fixing social experiences within memory, of building an archive of treasured ‘moments’ that form a personalized pictorial history of the individual within a cultural group. For Teller, this abrupt ‘point and click’ aesthetic reveals as much about the author himself as it does about his subjects. It is evident that this work, like that of Nan Goldin, is inherently linked to being part of a glamorous social scene – it’s about being able to participate in an enviably stimulating lifestyle, and it’s this that gives the images of both these photographers much of their seductive appeal.

What does Go-Sees tell us about the girls pictured, except that they are exploitable? What does it tell us about ourselves as viewers, except that perhaps we are exploitable, too? If we accept the offer to enjoy vicariously the pleasures that Teller documents, are we not – with our equally willing consumption – as guilty as he is? The reality is that the vast majority of the girls pictured in the book will never appear either on a catwalk or in a fashion shoot. Instead, they will have returned to university, to school or the supermarket checkout – undiscovered and, in the eyes of the fashion industry at least, imperfect.

EXPLORE ALL JUERGEN TELLER ON ASX

Download a PDF version of this article HERE

(All rights reserved. Text @ John Tozer, images @ Juergen Teller.)