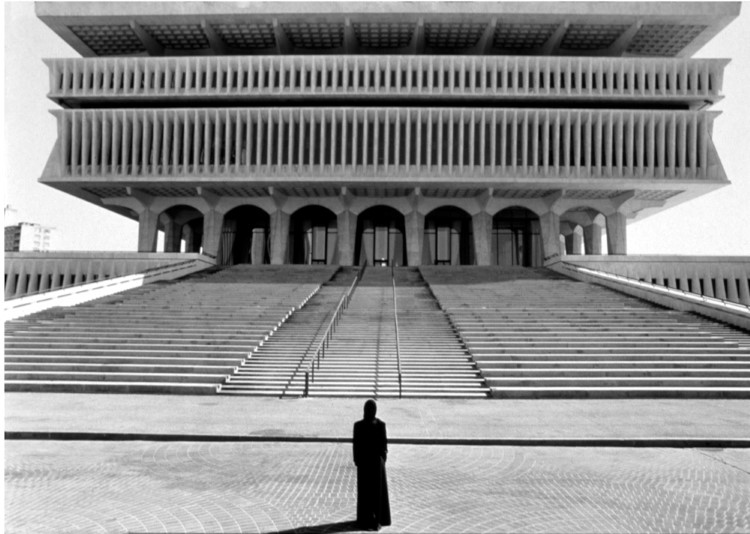

Soliloquy Series, 1999

Shirin Neshat. A conversation.

By Raphael Shammaa for ASX

January 27, 2014

Raphael: Shirin, your upbringing in pre-revolutionary Iran straddled both the religious and the secular. You attended Catholic schools, your grandmother was a practicing Muslim but your father’s thinking was progressive. Did you study the Koran at home or in school in any formal manner?

Shirin: Well just to clarify, it’s not just my grandmother; my whole family were Muslims. I grew up in a strictly Muslim family and even my mother and father were Muslim. It’s just they were not as strict about practicing it, and in Iran in my time, and I’m sure today, yes we studied the Koran at school. We don’t speak Arabic, and the Koran is in Arabic language, but we prayed and we went to the mosque and we studied the Koran in school.

Raphael: Was that part of the curriculum in Catholic school?

Shirin: No, I went to Catholic school for only two years. I was mainly in public school in my city. Of course in Catholic school they wouldn’t be teaching the Koran. That was a boarding school. I went for a short time in the city of Tehran, but the rest of my education was in the city where I was born, which was a very religious city. I think it’s the third most religious city in Iran.

Raphael: Is it really?

Shirin: Yes, it is very very religious, and there we studied Arabic and also the Koran, from what I remember, yes. We were all practicing Muslims, so it wasn’t just my grandma or anything.

Raphael: Well thank you for this clarification. And knowing what was going on in your own country while you were in The States, how was it for you to witness Tianamen Square, the Velvet Revolution, the overthrow of Ceausescu in Romania and the fall of the Berlin Wall – each of them the outcome of people rising against oppression and all of them taking place within the same twelve months in 1989, barely ten years after 1979, which was the year of the Iranian revolution?

Shirin: Well I grew up during the Shah period, and we lived under a heavy sense of censorship and there was a lot of social control and we had the Savak, which was the secret police of the Shah. It was as liberal as it may sound compared to this government, current government. It was really a hush-hush situation. There were a lot of student activists that were imprisoned. It was sort of forbidden to talk about Khomeini – because there were so many of them killed. Even at a young age I knew something was boiling up, meaning the frustration of the people who were religious and the frustration of students against the Shah’s tyranny, and then eventually what came out was the Islamic Revolution.

For me now, it is my understanding that nothing happens overnight. Everything sort of builds up over the years and it was no surprise that we had the Islamic Revolution. The groundwork took place a long time before that and I am one person who knew that. So my response to Tianamen Square and the razing of the wall in East and West Berlin was very much the same thing. It was the frustration of the people that eventually crystallized in a very strong reaction, and it made perfect sense, and for others who haven’t lived in countries such as that, or who have democracy, etcetera, I tend to think they believe it comes out of the blue, but in fact it takes 20 – 30 years, or more sometimes, to build up that kind of rage and determination to bring about a revolution.

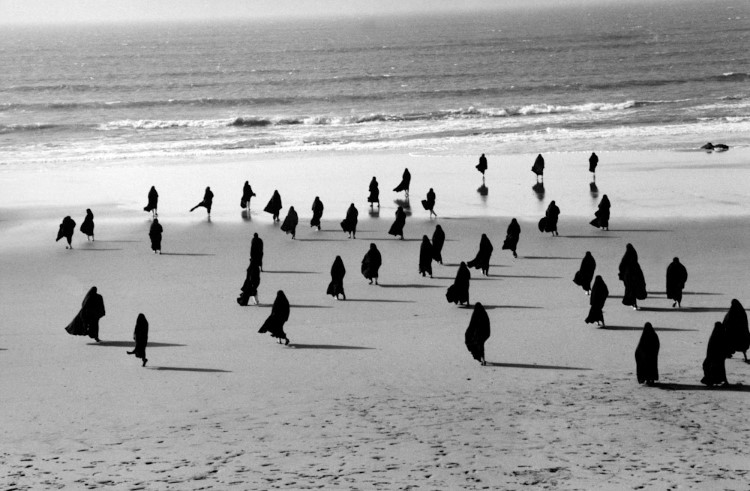

Rapture Series, 1999

Raphael: Yes, it’s a confluence of factors.

Shirin: Exactly.

Raphael: In 1990, after a 12-year absence, you finally go back to Iran. The militancy of Irani women and their changed outer appearance, you say, were a shock to you. Your work, The Unveiling and Women of Allah, are products of this shock. What was the process that unleashed your energy and activated your art?

Shirin: It was the very simple reaction of a person who had been away since the start of the Islamic Revolution and was inundated with a sense of nostalgia and a longing to reconnect; and when, of course just like any other Iranian, I went back, I really did find that the place had changed like day and night in terms of what I had remembered was there before, even the way people looked, the way that people dressed, the way the streets were bombarded with propaganda against the US. It was totally unbelievable that this was the same country.

Raphael: The prevailing tone had changed.

Shirin: Exactly, and for me it became an obsession to understand, from a strictly artistic perspective, some of the issues that were really relevant to the understanding of this transformation. I decided to really focus on a very key conceptual ideological issue of the Islamic Revolution, which was the concept of martyrdom. Martyrdom – meaning that people who were very committed to and had a strong conviction to their religion would be willing to die and kill in the name of devotion and faith in God; and to me that was really a kind of loaded concept that was almost institutionalized by the government. But even more interesting, I saw that even women in the Islamic Revolution were seen in that new way, I mean there were a number of publications and images that showed religious Iranian woman wearing the veil and yet holding weapons, and I found that amazing – a kind of paradox.

So I just kind of took that and ran with it in terms of not only framing the question of martyrdom, which is this obsession with death, and life after death, and the idea that young people should die and that their families should be congratulated for their deaths because they’re now in heaven but, more so, that women were placed within that context even though women are generally about giving life and birth and not about dispensing violence and death. So I just found that as an artistic and philosophical point of view a kind of fascinating phenomenon, and decided to develop Women of Allah, which pretty much explores these conflicting ideas.

Raphael: Is it a matter of concern to you that it’s easy to a casual audience outside of the Middle East to confuse Persian script with Arab calligraphy and to erroneously assume that the text overlaying your art in The Unveiling and Women of Allah is excerpted from the Koran instead of what it really is: contemporary, even feminist Irani poetry, a far cry from Koran texts?

Shirin: It’s a good point. There are two issues that frustrate me often. People in the West often cannot understand the difference between people who are Arab and Iranian. Iranians are not Arabs and we do not speak Arabic and we don’t write in Arabic, but we have the same alphabet, and you know also that Western audiences often rush to think that everything that we write is excerpted from the Koran, which I would never do. It would be so sacrilegious, and my texts are all Iranian text, Farsi text, and they’re all poetry. And another frustrating thing is that when I speak about my work, about my subject, people don’t understand that I’m really talking about Iran. I’m not talking about the entire Muslim world, because that relationship to Islam is specific to each country’s political history and about their specific relationship to Islam, in terms of whether it is an authentic religion, whether it was brought in by force, whether it was a secular religion or a non secular religion, so unfortunately there is in the West that rush to generalizing when representing me as someone who makes work about Muslim women. I don’t do that. I’m very specifically talking about Iran.

Raphael: You’re really focused on the product and the outcome of the Iranian Revolution and the effect it has had on women in the population there. So I wanted to talk a little bit about your short piece Turbulent. It’s a haunting video installation, and it features a man singing a Persian poem by Rumi and simultaneously, on a separate screen in another part of the same room, a veiled woman intones a primeval, wordless lament. The man sings to an audience, confident in his own talent and their appreciation of his art, and the woman to an empty room. But then the man seems to gradually become aware of the female voice reaching him across the chasm and he becomes transfixed by it. At this point the episode seems to transform itself into a call-and-response duet across space. Is this about hope? Is it an ode to receptive men willing to listen past prejudice and ignorance, or is it about women’s innate power to communicate something deeper and more powerful even than culture itself?

Shirin: Yes, I think it’s more about the second explanation. That piece along with two other videos is based about the issue of gender in Iranian society, referring to the fact that women often find themselves against the wall. This particular piece, Turbulent, is about women being forbidden to sing publicly or produce recordings. I was fascinated by how in general, women in Iran, the more against the wall they feel, the more defiant and innovative they become. I believe that if you look at Iranian society today you’ll find women to be remarkably rebellious. So that piece is more about looking at it through the rules governing music. The man sings a stylized, predictable, conceptual piece and is applauded by his all-male audience. And what about the woman? She’s forbidden to sing and therefore becomes creative and makes music outside sanctioned music or language and their rules. While she is rebellious, the man continues along conformist lines, a metaphor of Iranian society.

Raphael: Does the metaphor also stand for art in such societies?

Shirin: Yes, in fact the kind of expression you expect from women is very, very different from that of men’s. Therefore, whatever is created or is expressed by women is radically different from whatever is created or is expressed by males. And being a woman I’m very fascinated by Irani women.

Raphael: Of course. And in Rapture, women in traditional black Chadors busy themselves on a beach putting a small boat to sea, some, but not all, departing onto the open waters toward unspecified shores. Men in western clothes on the other hand, survey the scene from elevated rampart walls – hemmed in, moving about their enclosure with nowhere to go but the short distance to the next fortified wall. This work seems to present an inverse perspective on gender realities in Irani society from what we know. Is this a misreading of your work or is it a psychological portrait?

Shirin: Rapture is an allegorical piece just like Turbulent. It addresses important sociocultural issues in an allegorical way. If Turbulent is about gender in relation to music, Rapture is about gender in relation to nature and culture. And for me it is truly curious that religious women in Iran are never pictured as having any connection to nature – mostly represented as they are in urban environments; and I found it interesting to represent a hundred of them in Nature while representing men in a traditionally masculine space. I feel there is a common thread between Rapture and Turbulent where, in the end, women show enough courage to migrate from the desert towards the sea and, eventually, just leaving. As in Turbulent, they contradict standard expectations by resorting to courage and rebelliousness.

Passage Series, 2001

Raphael: Yes, in your pieces, men seem to be hemmed in by tradition, and women to be responding to their own nature.

Shirin: Yes, exactly. Your reading is correct. Both pieces are similar in their conceptual approach.

Raphael: You say that if we really want to know a society we ought to look at how its culture deals with women and how women are faring within that society, and you seem to position women’s status as the proverbial “canary in the coal mine”, a strong indicator of how balanced a particular society is.

Shirin: In a lot of Islamic societies women embody the rules of government, of society or religion, so their private lives are much more impacted by them than men’s, but I think this is changing and if you look at Iran today and even at my own recent work you’ll find women no longer abiding by government rules quite as much. They’re very educated and independent, they’re very vocal, and powerful participants in protests. In the streets of Tehran some women even dress in outrageous ways. They just refuse to mirror government dictates. At the very least they’re subversive.

Raphael: The brand new Tunisian Constitution enshrines women as equal rather than complementary to men. Do you think that will spread through the Muslim world any time soon, or at least have some impact?

Shirin: I’m very optimistic about President Rouhani and I have the feeling we’ll see some very good things happen to women as well.

Raphael: Incidentally, I want to ask you how different your career would be today without the advent of the Iranian Revolution and the dramatic rise of the ayatollahs?

Shirin: That’s a good question. Maybe I wouldn’t be an artist. I think it’s true that much of my work has been defined by the Islamic Revolution, by my reaction to it, and that my life has been defined by it. I’ve been separated from my family and live in exile, so emotionally and, I suppose intellectually, my work is my response to the Revolution and how it has defined a whole generation of people in and from Iran.

It’s fascinating how this revolution defines so many peoples’ lives, whether they choose to leave or stay and what kind of political decision they opt for. I haven’t seen my family in so long and it’s had a direct influence on my thinking, and yes, if all of this wasn’t an issue I certainly don’t think I would have been an artist, just talking about the weather or…

Raphael: Or not the same artist, perhaps.

Shirin: Yes. You know I stopped making art for ten years.

Raphael: Yes.

Shirin: Yeah, not the same artist. Maybe it’s a good thing [the Revolution] – or I would have quit altogether.

Raphael: And yet, although there is no fatwa against you, you hesitate to go back to Iran for reasons of personal security. Is Iran the only country you feel that way about?

Shirin: I think so. I think it is the only country.

Raphael: You directed a short for the 2013 Viennale with Natalie Portman and cinematographer Darius Khondji – both world class artists and you are proceeding with research on a film about Umm Kulthum, the legendary Egyptian female singer (in yet another Islamic country) with more or less the same issues. Does working on these projects, because they are not related to Iran, feel different than working on say, Turbulent, or Women Without Men – your award-winning feature?

Shirin: I think it’s very similar because in Women Without Men the main idea is the relationship between art and politics, the lives of certain women as Iran was battling a coup… I’m not sure if you’ve seen the movie…

Raphael: Yes, I have…

Shirin: With Umm Kulthum I feel that by making this film we’ll be navigating and taking the audience on that same journey. Once we’re with Umm Kulthum and her music, with art and mysticism, brought to the level of primal responses, we find ourselves elevated beyond time, politics or even history. We’ll use the music, the camera and everything else we have to take the audience to that state of ecstasy. Because she happened to live in Egypt at such a pivotal time in politics, we’ll take the audience through the age of colonialism, of social revolution, of the war with Israel and through defeat and economic disaster. We’ll show her at the center of all that as well as an artist. For me, this is potentially a similar concept – it’s about the underlying connections between individuals, the community, art and politics.

Raphael: Does serendipity play any role in your work despite all the planning?

Shirin: You know something, I believe in magic. For example, we have this opening at the Rauschenberg Foundation this week and it never occurred to me that the theme of the exhibit is about loss in the aftermath of the Egyptian Revolution, and that this month is the anniversary and that there’s violence there again.

Also, I’m just back from Davos, from the World Economic Forum, where I was given a prize and had to give a little speech. This year is also the first in ten years that the Iranian president agreed to participate. That was serendipity – an Iranian artist and the Iranian president.

And after working on it for years, Women Without Men came out exactly in the same summer of 2009 when we had the uprising in Iran. People thought we planned it like that, because there were all these shots of protest in the streets of Tehran in 1953, so yeah, I believe in magic.

Raphael: How would you like that particular body of work to be seen over time other than playing against its specific backdrop and time in history?

Shirin: Which body of work?

Raphael: The one that has to do with women within the Irani revolution.

Shirin: Well I’ve come to the conclusion that, in terms of my photographs, I’ve done two big bodies of photographs. Both of them have been human portraits. One of them has been Women of Allah, which basically captured a pivotal moment in Iranian history, which was the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The next body of work in photography, again a human portrait, captured during the Spring and Iranian Green movements another pivotal moment in Iranian contemporary history. For me, my photographs, the big two, are the only two groups of photographic work that I’ve done, each one of them representing a particular moment in Iranian history but neither reflecting what’s going on today. The Book of Kings, finished in 2011, represents a lot more of Iran today, but Woman of Allah should be looked at as something of the past and no longer of the present.

Raphael: As an engaged artist do you feel that contemporary art sometimes suffers from lack of content?

Shirin: Yes absolutely, I have two thoughts on that. I don’t insist on contemporary artists being politically active but they ought to be politically conscious. And if I could be that blunt, I think the art market has been the biggest factor in determining art movements for the past decade or so; and the money involved has seduced galleries, collectors and artists to becoming super rich and very, very distanced from sociopolitical issues; art has basically become a commodity and about entertainment.

Being Iranian came as a mixed blessing of course, because Iranian artists paid a great price, having to live in exile and being censored. You really have to suffer for what you do, but I have to say that I have not become just pure commodity and my work has been effective and has been heard by non-art people from my community and that gives me a lot of pride. So I do criticize the art world and the artist today and think that this was not the case before.

That’s why I’m so proud to be apart of the Family of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation because as a Western artist he definitely has a legacy in being politically conscious and an advocate for helping with different causes from education, to AIDS, to government, to asking for democracy. And it doesn’t mean that you don’t make highly aesthetic works but it still means that you should be engaged. I’m not saying that people shouldn’t be painting landscapes and things that aren’t completely outside of political reality but I think it’s important to be engaged.

Raphael: You were not born into the US culture, obviously and the country in which you grew up is no longer there. How does that reality play out for you?

Shirin: Yeah. This is the story of the new generation of artists that we are truly nomads. In my case I don’t even remember living in a place in which I look like everyone else and speak the same language. I’ve always been an outcast. It’s just a way of life. I am a storyteller and I find my way. I go to Mexico, Egypt, Morocco and Turkey and I make work that makes one believe that I’m in Iran, and this reality of never being in a place that’s your place of origin, has been a way of life.

Raphael: Is there are a part of you that wishes for a place that you actually belong and feel totally at home in?

Shirin: No, to be very honest. I’ve lived longer in this country now than I have anywhere else. My independence and way of life is non-Iranian in many ways. Inasmuch as I’m emotionally Iranian and I’m surrounded by a community that’s Iranian I don’t think any of us have the ability to go back to that idea of purity of just remaining in one place. I go to Egypt now and I feel so at home. I go to Europe and I don’t feel quite as home but I can adjust to it. I can’t go someplace where they tell me how to be and how to live, that there’s just one way of being. I just don’t know. I’d love to visit Iran but I just don’t know if I could ever go there to live permanently.

[nggallery id=601]

Shirin Neshat: Our House is on Fire, January 31 – March 1 2014, The Rauschenberg Foundation Project Space, 455 West 19th Street, New York

Shirin Neshat

Iranian-born artist and filmmaker Shirin Neshat has had numerous solo exhibitions at galleries and museums worldwide, including the Detroit Institute of Arts; Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin; Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montréal; the Serpentine Gallery, London; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; and the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. She is the recipient of various awards, such as the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale (1999), the Hiroshima Freedom Prize (2005), the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize (2006), and the Crystal Award at the World Economic Forum, Davos (2014). In 2009, Neshat directed her first feature-length film, Women Without Men, which received the Silver Lion for Best Direction at the Venice International Film Festival. Declared Artist of the Decade in 2010 by The Huffington Post, Neshat is represented by Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.

(All rights reserved. Text @ Raphael Shammaa, Images @ Shirin Neshat and courtesy The Rauschenberg Foundation)