From 41 Hewitt Road

By Niccolò Fano for ASX, May 2013

Anna Fox (born 1961) has been taking pictures for over thirty years, documenting her surroundings and reinforcing the strong tradition of British colour photography initiated and developed by practitioners such as Martin Parr, Paul Graham and Paul Reas. Her work is often described as typically ‘British’ in both the approach to subject matter and the highly saturated colour documentation of culture, social structure, peculiarities and customs. Fox’s focus often turns inwards; this is particularly evident early in her career where introspection plays an important role in the formation of her signature style. In recent years she has been recognized for her contribution to the photographic medium by being short listed for the 2010 Deutsche Borse Photography Prize, with grants for elaborate commissions and the publication of a monograph surveying her work from the early 80’s to 2007: ‘Anna Fox, Photographs’ (published by Photoworks).

In this extensive interview I talk to Anna Fox about her numerous projects, the difficulties and challenges of autobiographical photography, house co-sharing, villages, cockroaches and ‘the Anna Fox problem’.

NF: The structuring and understanding of the history of photography requires us to allocate practitioners within certain categories, genres or groups. Your work falls, somewhat unanimously, in the category of British colour documentary alongside a small number of photographers who’s images have focused on looking at Britain from a ‘different’ angle. How instrumental was the relationship with Martin Parr and Paul Graham – both lecturers during your time as a student – in the creation of your photographic identity?

AF: Vital to know is that my tutors were Paul Graham and Martin Parr and we also had Karen Knorr – Paul Reas was a student at the same time as me but in Newport and he had Martin as a tutor but not the other two – interesting to look at that the difference in our approaches based on that knowledge!

So all three lecturers were vital in terms of helping me to form my identity as a photographer – with Martin I admired his humour and was particularly excited when I saw his first colour with flash photographs from Last Resort which he brought out to show a small group of us when we went on a field trip to stay with him at his home in Liverpool – what a trip: six students staying with Martin and Susie Parr! I had grown up listening and watching the best of British comedy (my dad was a big fan of Tony Hancock and the Pythons) and Martin loved all that too – I could relate to this.

Paul Graham was quiet and determined and tended to be interested in the less predictable images; his editing (when he looked at our pictures) was always highly complex, intelligent and informed by his interest in politics/social conditions – his vision of what was interesting really made me question my beliefs all the time. He kindly offered me a space in his darkroom/studio in London (when I finished college) and without this I would never have made it through the early years. Paul also had a vast technical knowledge particularly with colour printing, this combination of intellectual enquiry and technical know how made him a real maverick and so very inspiring.

Karen was grand and quite intimidating at times, though always looking out for us – I loved her use of image and text, the irony she created was a key inspiration for me in creating the two series’: Basingstoke 1985/86 and Work Stations. Again – Karen was a master (or mistress) in terms of her craft and the way she combined image and text had an academic feel to it, was highly intelligent and helped me to realise new ways of making political comment in a body of work.

NF: The documentation of Thatcherism is a recurring theme for most photographers successfully surveying the cultural and social structure of British history in the 1980’s. Paul Graham’s ‘Beyond Caring’ (1984 – 1985) focuses on the unemployed, the unknown, those swept under the rug by economic liberalism and class war. In the same decade you produced ‘Work Stations’ (1987-1988) where the focus is on the opposite spectrum, the employed, competing in the everyday rat race. What is the thought process behind the project?

AF: Well in a way the intention was similar except, as you say, I was photographing the opposite. As mentioned above my influences had come from my tutors but at that time I had been looking at Suburbia by Bill Owens and thought it was a fantastically satirical narrative about modern North America, a desperately depressing and timely critique of the American Dream. At the time I made Work Stations I had not read a lot of fiction – mainly just the books we were asked to read for exams at school, most of the texts we read for our ‘O’ levels (taken at 16) seem to have informed, in some way or another, my later photographic work. In the case of Basingstoke 1985/86 and Work Stations and even Friendly Fire it was Orwell’s Animal Farm, 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World. Other literature, read at school, influenced later projects: Kafka’s Metamorphoses, Hartley’s The Go Between, Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and Golding’s Lord of the Flies all stuck firm in my imagination in relation to how a social landscape could be described.

Anyway – Work Stations was commissioned by Camerawork Gallery in the East End of London (now disappeared) and the Museum of London; the direction was to photograph London Office Life. So I did, for about a year and a half I gained access (via friends, neighbours and the commissioners) to about 60 London offices where I photographed with my Makina Plaubel (a purchase influenced by Graham and Parr who both used it) and a Metz portable flash gun. I went on one or two shoots a week – shot a mass of film – and each location was totally different. I tried to cover different areas as much as possible but this was never going to be a survey. It was relatively easy to get into most places especially as The Museum of London was one of the commissioners – we all like to become part of history and this is how I approached taking pictures of people – I spoke with everyone I photographed and explained what I was doing in these terms and a collection of the photographs went into the Museum of London’s photography archive. One or two people I did photograph before talking to them then I explained afterwards, I only met one person who said no to being photographed and there was one woman at the end of the project who decided she didn’t like the photo of her but by this time the book was on the printing press and it was too late so I had a meeting with her and we resolved the issue – she asked me if I could “airbrush” her skirt a bit longer so it covered her knees, I explained that it was too late and that actually her knees looked fine and it was all OK. I have some very funny stories about things that happened on some of the shoots but these are too long to write down here – actually I am planning a semi-fictional autobiography of a woman photographer based on many of my anecdotal stories – this will be a new project that hopefully could come out before 2018.

Every two months or so there was a meeting with me and the Camerawork Gallery committee / board – it was a bizarre meeting where they would look at the work and make comments – thankfully Anna Harding was the curator at the time and after the meetings she would just say “don’t worry about it, just keep shooting”, as the meetings were not in the slightest bit inspiring or confidence building it was great to have Anna Harding on my side. Camerawork wanted me to concentrate on women at work but I objected to that – I mean, it felt like they had employed a woman photographer simply because it would mean I would want to photograph women! I didn’t. I was more interested in politics, society and power structures within the working environment of the office and particularly in Thatcher’s Britain as the period later became known. All my family worked in offices at the time from the paper trade to the banking industry to a design office. I had worked in insurance prior to studying photography. Work Stations was a bit like The Office (that brilliant comedy that came out in the 1990s) but with less comedy.

In terms of making the images I generally relied on what I had learnt in college: I wanted to use colour and flash because of the very immediate feel that they give to the work – you really feel like it is happening here and now rather than in the distant past or far away when you look at this type of aesthetic. I wanted to make large-scale images (though no where near as large as todays photographic prints) that were sharp and colourful, I wanted to tell a story using images combined with texts that picked up on the social conditions of the time (Thatcher’s Britain – and her famous quote: “There is no such thing as society; just individuals”). I wanted to use humour, satire to engage the audience in what I was trying to say – I was doing two things, as I saw it: the first was to record history and the second was to make a critical commentary on society as it was and focus particularly on aspects that were not normally looked at by photographers – the middle classes. I collected the text captions in the same way that I made photos; getting into the right places, reading the relevant essays and magazines, interviewing people as I went around. I collected a vast number of quotes and statements and then edited them slowly. Once I got down to the ones I wanted I started to put them with the images that I had already edited in the same way. I played around with the combinations of texts and images for a while but in the end most of them were obvious in terms of what went with what – I liked the idea of creating a filmic narrative – or a short story about office life – by this time I had really started to read more fiction and was particularly interested in authors like JD Salinger, Raymond Carver and Carson McCullers. I was also interested in the intriguing narrative structures used by Paul Graham, Robert Frank and Diane Arbus amongst others. I wanted to find ways of telling a story, using photographs and text, that was more like a work of fiction (as in a novel or short story).

So I think that was the way I made Work Stations – finally the work was edited down to 35 pictures for the book and 36 for the walls of Camerawork Gallery where it first opened – it happened to be 36 on the wall as I decided on one extra at the last minute. Anna Harding selected the final images with me. She had some great ideas and we had some disagreements – it was a real learning process for me – she was very good – I don’t think I realised at the time how important the curator is – I do now!

NF: Looking at the overlooked, as you have mentioned in one of your lectures at Newport University, has been a defining aspect in your research, an inspiration for your work. How is this translated within your photographs?

Well I think what I meant was that instead of looking at either news type stories or stories that are primarily exotic I am generally more interested at looking at the everyday, at what is in front of my nose or around the corner, under the bed etc. I feel that the most interesting photography does this: observes what most of the world ignores and dismisses as dull or “too ordinary”. When I photographed office life in London for Work Stations hardly anyone had photographed the office environment (more have now), Basingstoke 1985/86 (one of my first projects) observed life in a 1960s new town – again a subject not considered interesting particularly by British photographers at the time. Cockroaches in Cockroach Diary – very everyday and never photographed like that! Cockroach Diary was a project that observed and recorded the comings and goings of cockroaches from my home in London, the photographs all shot on a small auto focus analogue camera (and often shot without looking through the lens) were accompanied by a handwritten diary text that described (in my voice) the comings and goings in the house and the way we (a group of house sharers) argued and were unable to deal with the infestation – the story was a metaphor for the contemporary conditions for young people sharing a London house, it was a tragic comedy of sorts.

NF: By looking at the images and text from ‘Cockroach Diary’ and ‘Afterwards’ it seems to me that dynamics within co-sharing apartments haven’t changed…. It might just have something to do with the fact that we both studied and lived in precarious housing in the south of England. Tell us about those years, the parties and the creation of these two bodies of work.

Cockroach Diary was made ten years after I graduated and we were still sharing houses! – The kind of photography I was doing meant it would be hard to earn enough money to live alone or just with my family. One year I lived in a van with my partner and baby! I bought my first bed when I was 40 – up to then it was always a roll up mattress on the floor – I spent money on film, equipment and printing before anything else. I now have a full time Professorial position at University for the Creative Arts so things are different.

Cockroach Diary was made inside 41 Hewitt Road, a two story attached Victorian house in North London. 41 Hewitt Road became another book project when I selected a series of images made in the house (none included people and they looked like I had discovered the place rather than lived in it) and brought them together with a series of emailed memories from people who had visited the house and a set of still live photographs of strange objects that I found, all individually wrapped inside three cardboard boxes, (I found the boxes some years after we had moved out of the house). The objects were all very eccentric (as was the house) and I didn’t unwrap them (after moving) for about four years. When I did unwrap them they were unusual enough to warrant photographing so I turned the boxes into mini-studios and photographed each object as a still life. A Japanese cockroach trap, a toilet roll with a small hole in it, a sad poem called “Winter” written by my son mounted on blue sugar paper, a brooch from a junk shop, a paper plate decorated with three Welsh women in traditional dress (tourist trophy) whose heads had been replaced with footballers heads in an act of photo montage, a hand made paper container for taxi business cards, an unpainted plaster cast of a dog – these were the kinds of objects I unwrapped and photographed. Four years on it seemed astounding that these were things that had been so carefully saved. After photographing I rewrapped everything and it became “The Hewitt Road Archive, currently in storage”. So Cockroach Diary was made in the house too and I simply photographed the Cockroaches and kept a diary of what happened, it was another cathartic project: I really was terrified of the cockroaches and I hated living in the house with all those people. During the shooting of the project people slowly left, we had various arguments all documented in the diary, until there were only two of us left, myself and Abi, she with one son and me with two. Once we all left and I moved to the country and started photographing rural life again in Back to the Village – which literally meant I was back.

From Cockroach Diary, @ Anna Fox

Afterwards was an odd project in the sense that it was the first time I had delved into my archive and dug out pictures that I had not thought of as being a series when I shot them – from the 1980s onward, in my mid twenties, I generally took a camera everywhere and so a number of house parties were photographed and they seemed to be the same sort of student parties that continue today. Later in the 1990s I started going back to where I had lived as a student and photographing the same people who were having similar parties. The parties were slightly different as they were post rave culture parties; they were more intense, always lasted all night and modelled themselves on raves – mini raves. By the time I started photographing them public raves had virtually been banned so it was as if everyone was trying to re-live the experience. I edited the series together with Val Williams for the first Shoreditch Biennale (a photography festival that she and I directed in the late 1990s). Val was interested in the idea of “Afterwards” and this fitted nicely with the feeling that I had that Rave culture had been killed off and that these bodies exhausted at the end of a party represented the idea of “Afterwards” quite precisely – so we picked a series of primarily prone bodies from the end of parties and hung them as a set of six simply calling them “Afterwards”. Some people thought they were scenes from a war – it became very interesting for me to consider what happened when no explanation was given with a set of photos and how this work really stood to signify the end of an era as opposed to having anything to do with the people in the pictures or even the parties. One of the images from the series was from the 1980s (when I was a student) the rest were from the mid to late 1990s when I went back to visit my past. I still felt like an insider, as these were people I knew, but I had moved on (up to London away from the country). I had missed out on rave culture as it happened when my children were young, so perhaps I felt like I was trying to catch up. Everyone knew I was taking photographs and I printed pictures for the people I photographed when they wanted them, I tried to avoid showing too many faces as the work was not about individuals. I always stayed up all night to get the images at the end of the parties. Sometimes if I was tired someone else would offer to take the camera and carry on – it was the same analogue auto focus film camera that I used for Cockroach Diary.

The final Afterwards prints were made by Paul Graham – As mentioned previously Paul had offered me a shared space in his darkroom, this kept me going, but the negatives for Afterwards were so poor and I wanted them very large (2.5 x 1.3 metres) and I could not manage to print them myself. Joe’s Basement (Lab) took one look at the negatives and said “ no-one could print these”, Paul offered to do them – he is an extraordinary craftsperson and managed to make six beautiful prints. They were then sealed in plastic and hung in a deserted school playground in Shoreditch, one of the venues for the festival. The bodies looked even more vulnerable and disturbing like this – their frail frames exposed to the elements and in a brick built institutional courtyard.

All this work: Cockroach Diary; 41 Hewitt Road and Afterwards was very much inspired by working alongside Val Williams – she pushed me to think differently about photography and enabled me to break away from what had become a rather formulaic approach to documentary photography. It all happened at a time where there was a lot of critique of the whole colour documentary aesthetic and how we were all photographing people in a way that was considered unflattering – so it was a challenge to turn the camera on my own life.

NF: You seem to focus extensively on others, groups and individuals, although one of my favourite projects is poignantly introspective and somewhat heartbreaking, ‘My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words’. Have you used photography, as many have done in the past, as a tool to eradicate and exorcise some of the woes associated with the difficult issues we all face in our lifetime?

AF: Yes, I have explored using projects and the camera to “exorcise” difficult issues – the work in this book was made at a time when my Father had been ill for several years and was wheel chair bound – it was a difficult time for everyone in the family but most of all for my Mother. She looked after him until he died over ten years later – a heroic job. I always have a project like this on the go but I don’t often get them out in public and sometimes destroy them – I think autobiography is insanely difficult and one has to be absolutely sure that it is necessary to do before making the work public. I made the work quite quickly and quite secretly: I kept a notebook on me at all times when I was in my parents home and simply scribbled down my Father’s rants, in particular the ones that were about my mother, my grandmother and sometimes me too. These quotes pointed to something desperately wrong going on, a terror of women and an attempt to squash the life out of us. Then I remember suddenly thinking about the neatness of my Mother’s cupboards and I saw them as a reaction to My Father’s words. I photographed the cupboards to deliberately exaggerate the neatness and that neatness became violent like the quotes. I designed the book myself also in a very deliberate way, like a beautiful miniature prayer book with light weight pages and pale pink covers; both texts and images showed through the pages, layering on top of one another like menacing couplets. On the front of the book it simply says “ My Mother’s Cupboards” and the reader does not immediately look at the back that has the other part of the title – “ My Father’s Words”. The text, including the title, is all written in a gentle scripted font, printed tiny on the page so the viewer has to get close up to read it. It is all designed to draw the reader into what looks like a quiet project then when their face is right up close to the page the words scream out at them – the photographs become invested with a distinct sense of claustrophobia – a shock.

NF: You have been photographing Linda Lunus for over 30 years. Who is she? What is your relationship with her?

I met Linda when I was in my early 20s when I was beginning to get really interested in photography and always had my camera. I had met a music writer, Paul, who lived near me and I started working with him: he wrote the articles and I took the pictures – we published them in Zig-Zag Magazine, which was a brilliant punk type magazine in the 1980s. There were a couple of recording studios round where we lived and we did articles on Test Department and Mark Almond amongst others. One day Paul decided to do an article on small town punk bands so we photographed our town’s best punk band – Afterbirth – the band was headed by Alison Goldfrapp, there were two guitar players and the drummer, Glen. I carried on photographing Alison for years after she left the band (this work turned into the project Country Girls).

When Alison left the group Linda took over, I had become quite friendly with Glen and when Linda joined the band she really wanted to be photographed all the time – she was into promotion and she loved my photographs of her. So I generally photographed Linda and the band when they practiced (I preferred practice to live gigs as it was easier to get in close and really concentrate on the character). I did group shots for them too which they used for publicity. I photographed Glen a few times but he was too shy to become the centre of attention. Soon Linda wanted more photographs of herself mainly to create a portfolio to try to get modelling work – she always called me. I don’t know if I realised at the time but I certainly know now that Linda is an extraordinary character: she always dresses exactly as she wants and has a vast collection of costumes, all totally unconventional. She has dozens of characters and never intends to conform to the conventions of how we, as women, are told we should dress. I suppose this was appealing to me as I had been brought up being told that I always had to look a certain way and it was soul destroying – Linda was, and still is, a breath of fresh air. Eventually I got a bit fed of being called up all the time to take photos so I talked to Linda about the idea of photographing her more and turning the whole thing into a project that we could continue and that we could both use as opposed to me simply making photographs for her folio. She loved the idea and there it began more seriously.

Since then the work has taken several turns and Linda now lives five hours away from me (we were virtually neighbours) and I only photograph her once a year. We once made a film about the work and during the film we swapped roles – Linda dressed me in a few of her outfits and I taught her to use the camera – it was excruciatingly uncomfortable and the film was a bit ridiculous (to me anyway), I hated being the model but Linda loved being the photographer. She then bought a camera and now gets her son or her husband (Glen) to photograph her – our intention is to combine her photographs with my photographs. Linda is also writing her life story, we would like to make a book of this work but its hard to think how to do it as it is never finished – I think the only way is to make it as a series of chapters all published separately.

I started this work, Pictures of Linda, when I was a student and I was living in the village of Chawton in Hampshire. I have an archive of work that I took in the 1980s before, during and after I was a student. I lived in Chawton House which was a deteriorating mansion owned by descendants of Edward Austen. The Austen family lived at the parsonage in Chawton which is now a museum. Edward Austen married into the Knight family who lived in the Tudor mansion, Chawton House, just nearby. By the time I lived there Major and Mrs Knight owned it and two of their sons and their families lived there too. Each of the three families lived in distinct corners of the house as most of it was falling to bits. One son lived in the attic and one in the cellar whilst the Major, with his wife, lived in a corner of the East wing. That left the centre and west wing of the house to a group of strange individuals who each paid £8 per week for a room and shared a bathroom. When I first moved there it was crazy – there were four of us officially living there and about ten or more hangers on. Everyone was taking drugs of one sort or another and we all shared a massive oak panelled living room with chintz curtains – it was as big as a tennis court with a huge fireplace with fire dogs and a spit to roast meat (which we must have done once or twice). I have a few wonderfully anarchic photographs of life at Chawton House – not shown before and dug out for this interview – this is where I first met Alison Goldfrapp and Linda Lunus.

All the punks and rockers hung out at the house, it was a fairly non-stop party, there were no students there except me; I worked for the first few months before becoming a student then left almost a year after I had graduated. The others who lived there at the beginning, Pete, Tony and Kim all worked, the hangers on were mostly unemployed. The rooms were massive and we lived a wonderful existence (for young people), there was a priest hole in the stairs where an escaped criminal wanted to hide – Pete was in charge (an ex-marine) and he managed to keep most of this type of trouble at bay – in fact he and I were kind of in charge together: I dealt with the land lady and directed the cleaning up, Pete dealt with the difficult hangers on and any one who was having a tough trip or come down. Towards the end it all changed. The Knight son, living in the cellar, had enough of us and wanted to swap his place for our extensive apartments. His mother agreed, most of our group moved out and three new people moved in. I didn’t enjoy living in the cellar and the company was not such fun as upstairs. Too much dope was smoked, everyone seemed like they were in a coma, it became incredibly dull. Eventually, shortly after I graduated, I moved to North London to live with a group of Farnham graduates in a big shared house in Willesden Green. When that didn’t work out my partner and I moved to share a squat with Alison and another musician in Islington.

NF: As a very distinct shift in scenery, you seem to concentrate extensively on particular villages and rural areas in Britain and have produced over the years a very diverse collection and documentation of life in the countryside. Why the village?

I grew up in villages and my grandparents lived in villages. I am very familiar with village life and it is interesting to photograph things you are familiar with – even if I travel far away I tend to photograph things or aspects of life that I have a connection to. Villages and rural life have been romanticised by photographers since the earliest days of photography and because of this many aspects of what life is like in rural Britain are frequently concealed. I am interested in revealing something of the life behind the scenes steering well away from the mythical picture postcard images of twee thatched cottages or rolling green hills. Historically fiction writers had been much more revealing – I love Jane Austin’s satirical observations of English manners and particularly the way she revealed many new things about women’s lives. Later I became fascinated by John Moore’s fictional accounts in his trilogy centred on Bensham Village.

I first photographed for the project The Village in the West Sussex village where my grandmother lived and my mother had grown up. It was a way of exploring the social values that I had been brought up with and I was interested particularly in women’s lives and about how we operate in a patriarchal society. I used photography to discover something and often what I discovered was a surprise, photography helped me to articulate things I thought or felt but definitely couldn’t say – it gave me the confidence to speak and was incredibly liberating. I had not realised how sinister a scene I would set in what looked like a twee English village.

The project, The Village, was commissioned in 1991 by the Cross Channel Photography Mission (now Photoworks), other photographers were commissioned included Karen Knorr, Peter Kennard and Julian Germaine. The idea was that we had to make a comment on the impending changes to the UK with the opening of the channel tunnel. I wrote a proposal stating that I wanted to look at the possible changes that might happen for women in a small, largely middle class, village. I had excellent access to everything I wanted as it was a close-knit community and my grandmother knew everybody. I started photographing in the same way that I had photographed Basingstoke and London offices and collected quotes in the same way. I thought I was going to put the two together but the more I tried to do this the less it worked and felt quite lost for a while, it was difficult to find a new direction and I was a bit bored of the idea of simply repeating myself and worried that if a style becomes too dominant then the content and meaning of the work could dissolve.

Nearer the end of the shooting period we (CCPM and I) invited Val Williams to write for the project (I had met Val first when she interviewed me for the Oral History of British Photography in the mid 1990s). Val wanted to do something different, she wasn’t interested in writing a conventional text for the project and she started looking through all the work. She asked me about some of the darker images that I had not yet selected saying that she found them strong and disturbing – this appealed to me, her interpretation linked to how I felt about the place. It was then that the project really took shape. I gave Val all the text that I had collected, quotes and village magazines etc. She selected ten quotes and then we went to the National Sound Archive and they helped us to record a soundtrack which included Val and I whispering the quotes mixed with another soundtrack (titled: village) playing in the background (it was mainly birds and bees and rustling leaves). Examples of the whispered quotes are:

We shouldn’t have to feel too guilty

We are an island

Only Housework for women

We are sending toys to Romania

If you listen carefully you can hear the voice of God

Don’t forget the homeless

Please give generously

So then there were a series of dark (literally and metaphorically speaking) colour photographs of village events (mainly images of women) and the soundtrack. We discussed the work more and then I went out and made a set of black and white photographs of the gardens (that I saw as being predominantly controlled by the women in the village) and photographed them as if I was a spy – I peaked through hedges and looked at them like empty stage sets where something was about to happen or had happened – this was inspired by a story my mother had told me about one time she was playing make believe in her dressing up clothes in the garden and someone was spying on her through the hedge – it was a creepy story. Finally I collected lists of all the jobs women had done, how long they had lived there, the names of their houses and the names of the flowers they grew – I think this was Val’s idea, she was particularly interested in the book Akenfield by Blythe (1969) which documented village life through interviews with working labourer families – it was a beautifully written prose text that had a documentary feel to it (because of the interviews), it shocked the public as it was the book that destroyed the rural idyll that so many people believed in. I now live in the village where the famous naturalist Gilbert White lived in the 1770s – his book the Natural History of Selborne has also been a great reference: a series of letters written to a friend about the natural history of Selborne and its surroundings. The letters are full of amazingly visual descriptions of the weather, birds and some aspects of social life, though he avoided the nasty bits and contributed to the mythologizing of English rural life. I made Back to the Village in Selborne and surrounding villages, I started when I moved there in 2000. I have also been working on a much larger project based on the Gilbert White book; it includes imaginary letters that I write to a “city friend” with photographs of local weather and wildlife (though avoiding the tropes of this type of photography). The work will eventually be a book titled “The Natural History of Selborne, Part 2, after Gilbert White”. There are many versions of the White book, each one illustrated in different ways and sometimes by very well known illustrators such as Eric Ravilious.

Going back to my first body of work on rural life, The Village, all the different parts of the project came together in what I now describe as an installation. There were black and white photographs spying on gardens on the walls of the gallery, (beautifully printed by Dirk Sveringen), then there was a box in the centre of the room where the colour photographs were projected and the whispering sound track played like menacing gossip – a floral curtain (virtually out of the village) covered the doorway – the box was 6ft x 6ft x 8ft and was very claustrophobic – it represented the heart of the village. The lists were printed on A4 sheets and left for the audience to take away – it was first shown in Worthing Museum and since then has toured to other venues and some modifications have been made. The interior of the box was small, I had bought three carousel projectors and, after advice from Andy Golding (the master of tape slide presentations), I also bought or borrowed wide-angle lenses so that the projections were as large as possible inside the small box. Martin Parr lent a set of interesting speakers and Sandy, a friend who knew how to build, helped with the box. Building the box in Worthing Museum was a nightmare – photography shows at the time had never included any installation and the Museum staff were very suspicious of us – Sandy and I building was a strange site to them: I was a bit hippyish looking and he was a massive ex paratrooper, and once, when they got particularly nervous, they locked us out of the Museum – building boxes for photography exhibitions was definitely not the norm. The photographs projected inside the box were all the dark colour photographs I had taken of village events and some in people’s homes – faces and limbs were grotesquely stretched across the walls and corners of the box. I had shot these images in film (using the Plaubel) and then printed them as 10×8 prints and then re-photographed them on 35mm transparency film on a copy table – they had a lovely rich dark quality and the way I had used the flash, lighting only parts of the images, made them look like stills from a horror film. The images were filmic and theatrical, later I realised they also had a Caravaggio type feel to them (in terms of the lighting) – I had been totally awed by the use of colour and light in the work of the Renaissance painters that I had been introduced to in 6th form. I was also always interested in experimenting with light, exposure and colour.

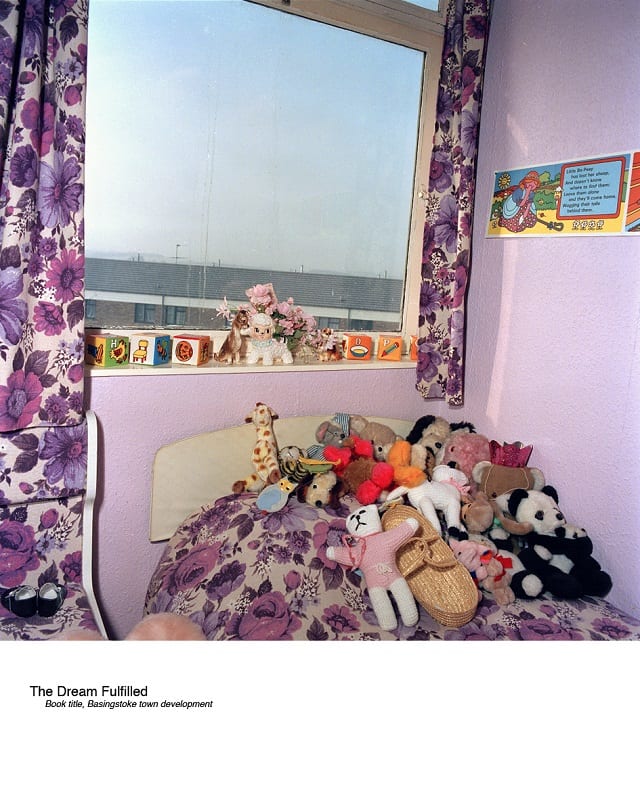

Child’s Bedroom, Basingstoke, 1986

The Village was an unusual show and people seemed to enjoy it, I had wanted to break away from the style I had developed in Work Stations and Basingstoke 1985/86 and this was about as far away as one could get, yet the meaning of the work was not altogether different. The Village had a more personal feel than my earlier work as I had moved a little closer to looking at my own family yet I still wanted to make a social comment. I wanted the work to speak about middle class values, to critique them and point out how the middle classes had slowly taken over many rural communities in the South of England. Often referring to themselves as “original villagers”, the residents of this small West Sussex village, had mainly come out of London after the Second World War. They had bought cottages, farmhouses and land from the landed gentry who were running short of money and moved many of the farm workers out. By the time I was photographing there were about two farm-labouring families left and one of the elder women in one of these families (who I interviewed) told me to “ never imagine that villages were friendly places to live”. Her house was still owned by the farmer; heated by a solid fuel fire, with only a few radiators downstairs. Her bathroom was at the back, made of breeze blocks and had no double-glazing. The two cottages (attached) to her left were also both owned by the farmer. He had gotten rid of the farm workers some years back, had modernised the cottages, put in double glazing, new carpets, central heating and was renting them out as holiday lets for about two months a year. The woman who I interviewed was bitter about this. I learnt a lot in The Village, at the time I made the work I was living in Aldershot, I then moved back to London (where I had lived in the late 1980s) and in 2000 I moved back to the countryside near to the village where I had been brought up and where my parents still lived.

NF: It seems to me that your village work functions as a solid foundation for your most recent commissioned project, ‘Resort’, where you turn your attention to the phenomenon of Butlin’s. Tell us about Butlin’s as an institution, the decision to divide the project in two parts and the difficulties encountered when approaching a large commission.

Butlin’s is a holiday camp first opened in the 1930s by Billy Butlin, who had come out of the circus. He had the idea of giving working class families the chance to have a holiday. The camps were designed for families to have fun, there were services offered to look after the children in the evenings so parents could go to the bar or to see a performance. There were shows, events, exercise classes and games all organised and overseen by the sociable Redcoats – the Butlin’s employees who were the public face of the organisation and helped everyone around the place always appearing to be your friend.

I was invited by Dr Roni Brown from University of Chichester to come down and look at Butlin’s in Bognor Regis with the idea of making some work there. Roni had made the connection with them and as a design historian was interested in the fabric of the place, it’s history and the attempts that the new owners had been making to re-vitalise it and “modify the brand”. The company who now own Butlin’s wanted to modernise the holiday camp experience and promote it to a wider potential clientele – they want more middle class holiday makers to come. Roni also discussed the project with Pallant House Gallery who decided to commission me to make the work with sponsorship from Butlin’s and University for the Creative Arts. I also won a Media Museum Award (sponsored by James Hyman) to help towards the making of the work. Once all this was in place I arranged access to the camp via the director, who was mostly very helpful though none of the on site staff ever seemed to know I was coming, making it difficult at times.

I set out to photograph the family holidays but when I arrived and found out about the themed adult party weekends I immediately wanted to photograph these as well. The Bognor Regis Director seemed pleased for me to do everything I wanted, the only thing he didn’t want me to photograph were the chalets, he felt they were too shabby – it was a shame as these were all that remained of the old Butlin’s. In any case I did not really want to be nostalgic about the place – I was interested in the modern face of Butlin’s and what it was being transformed into. I started photographing with medium format cameras, first my 6×6 Rolleiflex 6006 then the Plaubel (I mainly used this for landscapes as it is so light and easy to use – I don’t like it much for photographing people as the closest focus is about three feet and this sometimes feels restricting). I was not entirely comfortable at first photographing the families with these light-weight portable cameras, I needed to be able to have more of a conversation with people and to slow the process down. Unfortunately nobody wanted to slow down and talk as they were on holiday packing in as much fun as possible. So it was easier to start photographing the adult parties where people were dressed up in fancy dress according to the theme, drinking a lot and really wanting to be photographed. I also decided to bring the 5×4 Linhof field camera that I had inherited from my father who was a keen amateur photographer. So I had three cameras with me and as well two assistants: my partner Stephen, who loves talking to people which was vital (as I was often quiet behind the camera) and a great technical assistant Sveinung Skaalnes (by now I had been teaching for many years and was Course Leader of photography at Farnham – Sveinung was a graduate of the course). It helped that they both loved the Butlin’s experience; Sveinung because he was Swedish and the place was exotic for him and Stephen because he had been there several times as a child and had a deep affection for Butlin’s. We were in one of their best suites; it was in fact a kind of miniature (as in everything was scaled down in size) house – like a dolls house – and it set the scene for me as to how I began to feel about the whole place: Butlin’s was simply a set of theatrical stages where different acts could be played out, all of the acts would be things one might dream of being part of a perfect holiday.

The miniature house was a stage too: perfectly brown and beige; a bottle of sparkling wine in an ice bucket; three tiny bedrooms with half size beds; a small sofa; TV and kitchenette with instant coffee sachets like in a hotel. Everything was set up for a series of dream-like fantasies – the kind we all played as children with our dolls houses or toy racetrack or train set. The camp itself also seemed to be completely walled in and although the beach and sea were just outside (literally) the only place you could see them from was a few of the balconies in one of the new hotels – so hardly anyone thought about the sea being there – it certainly was not one of the stages.

The first weekend we went to was called “Back to the 60s” and the Troggs played one of the evening sets – a fabulous 60s band who I had longed to see as they had sung Wild Thing, a great favourite of mine. It started Friday night and we watched people arrive lugging massive cases (full of costumes) and crates of beer – which surprised us as we thought this would not be allowed. By 9pm the party was raging all over the camp and at all the different venues including three different stages, a pub and a nightclub. The costumes were brilliant, all very authentic and it was amazing to see the effort that had been put into this. People seemed to wear different costumes each night and the weekend lasted three nights. We only managed two nights because we partied as well as taking pictures so were all exhausted. I also tried to use the Linhof hand held for the first time – Sveinung organised the dark slides and I attempted to get the focus as correct as possible, we were inside the dance area of the Central Stage literally dancing around with the 5×4 camera and photographing anyone who wanted to pose. I took ten 5×4 colour photographs as well as masses of 120 shots – only one of the 5x4s was in focus – I realised when I printed the 5×4 image how amazing the detail was and this meant I could make incredibly large prints and that the scale would really monumentalise the subjects – this seemed exactly right. I went to a few more of the parties, the best one was the summer party, Stephen and I went twice to that, they were packed and masses of men were dressed up as women. There was a great gang of Welsh men who came as fairies, a couple of nuns who turned into bowlers the next day, a wonderful group of elegantly dressed and hatted ladies (men) who looked fit for the races as well as a group of women all dressed as Amy Winehouse, two groups of Elvis’s, a group of surgeons, monsters, honalooloo girls (men again) and many more.

I made a lot of photographs – I think my favourite was a bald fairy in a vivid pink tutu, cigarette hanging out of his mouth and texting on his mobile – the sky was deep dark blue behind him looking like a storm was about to break. Many of the party goers were on hen and stag nights, some had their sexual preferences printed on their t shirts, others had phone numbers inviting callers to call if they liked what they saw. These were big events (as if it was carnival in the whole town) and aside from the surprise of seeing so many people in fancy dress I was also surprised by how safe it all felt, the security guards were always around and if there was any trouble (I hardly saw any) they were quick on the scene – this made the environment much more fun than the Friday/ Saturday night streets of most British towns where violent fights can break out at the drop of a hat.

At certain points I dropped a few photos to the director as I was keen to know which ones he liked – he seemed to like everything I showed him and it wasn’t until a few weeks before the second summer party that he suddenly started to say that he wasn’t sure about the adult weekend break photographs. After that second summer party he called and said no more party photographs could be taken – I couldn’t get into another one. He didn’t give a reason and I immediately realised that the decision must have come from higher up the company as there had been no complaint at any time when I sent in images of earlier adult weekends. In the end we had a lunch meeting at Pallant House Gallery with Simon Martin, the curator, Roni, myself and the Butlin’s director and it was made explicit that due to the impending 75th anniversary celebrations the adult weekend party photographs could not be used in the 2011 exhibition at PHG. We were all disappointed but I did understand the situation and I agreed to this as well as agreeing that there would always be two distinct series (later titled Resort 1- family breaks and Resort 2 – adult parties) and that they should not be exhibited or published together – the main thing is that the adult weekends should not be seen amongst the family holidays. Again this made sense – I would never have intended to mix the two series’ up.

So as I had been effectively banned from the parties I started to concentrate in earnest on the family holidays. I still felt awkward with the medium format cameras so I asked Vicki Churchill (a fellow teacher and also a lighting expert mainly for commercial and fashion shoots) if she might come to assist with the 5×4 camera and some portable lighting kits. I had been very impressed watching Vicki work to light Neeta Madahar’s portrait series Flora (I was one of the portraits) – she was calm and capable and very friendly – I knew Vicki would be the right person on a documentary shoot with families, big camera and lights involved. So we did a day together, Stephen also assisted with getting the model release forms completed as this was now essential with families involved. During that day I had to really learn to slow down: big camera and lights is a different operation. We had a couple of trolleys and we moved around the camp like a caravan trail looking for locations. I think we took 3 shots that day and one really worked – it was in the new Ocean Hotel restaurant with pink walls and floors, bright yellow bucket chairs, a vivid blue sky beaming through the mirror-like windows and a family of four sitting in the right place eating lunch. They agreed to be photographed and we had to hurry to set up as I didn’t want to make them re-run their meal. Vicki worked fast and the lights were put up – Stephen had to guard all the wires which were a bit of a hazard – I set up the camera and Vicki set up a 35mm digital next to it – this was useful as it meant the family could see the photograph quickly, it also meant she could test the lighting before I shot on the 5×4. I think I took two or three 5×4 photographs, after that the daughter started playing up to the camera so much that it was pointless to continue and I was keen to get out of the way so as not to spoil their meal. I really prayed that I had got the picture and when I had them processed I was relieved to find that one worked – the colour and the light was so much stronger than I had expected and the detail extraordinary – the blue lettering on the back of the husband’s t-shirt matched the blue of the sky and the blue of the pushchair frame, there was also a tiny dribble of coffee running down the back of one of the yellow chairs (not visible in small prints!) – it felt like a real seaside image without the sea. So from there we became a team, I started to realise how great a team could be and far more fun than working alone. Vicki eventually persuaded me to hire a medium format digital camera to back up the 5×4 and this meant I always got the shot as I could shoot more on the digital.

The team grew to include 1st camera assistant Andrew Bruce – who is extraordinary calm and good with cameras and ideas – Jenny Patterson who worked on the digital capture, Vicki who continued with lights and a great band of 2nd assistants who managed lights, model releases, talking to people, safety etc. We did around seven shoots like this and a maximum of four or five sets per day and with each set I managed to get one image. There were one or two problem sets particularly at Christmas when there were so many people and so many flashes going off that our lights kept triggering at the wrong time. There were problems with the Butlin’s staff some of the time as they didn’t seem to know who we were or what an earth we were doing there – the director did not seem to have communicated anything to anyone. When I processed the Christmas shots there was one image that I really wanted to use but none of the three shots taken worked – I asked Andrew Bruce to try joining parts of all three negatives to make one image and he did an amazing job – he knew what I was after and interpreted the digital post production brilliantly. I spent weeks considering this image, initially bothered by the knowledge that it was joined I slowly got used to the idea and a few more were altered – amended to be more like the photograph I wanted through joining one to three shots. This was made much easier by the fact that I had shot on a tripod and the frames were the same. This technique has of course been used before but I could not think of when it had been used in a documentary series that included people – and despite being initially bothered by the construction, I eventually came to the conclusion that this interference was no different to the actual act of framing the image (and in so doing missing things out from the edges). I was choosing to add things that had been there (a few seconds before) and possibly were still there (concealed by a lack of light due to technical problems with lights going off at the wrong time). I think four in the series were changed.

From Afterwards

Finally I wanted some of the images printed as large as possible and there was enough funding to make two photographs approximately 6ft x 8ft – all the prints were light jets so there was scope to play quite freely with colour and saturation. Most of the prints were made by Dave at Goldenshot whilst the two large ones at Metro in London. The large prints were illusory and in the exhibition two children tried to get into them, thinking that they were real rooms. The final difficulty came when the work was actually being printed and Butlin’s emailed to say that four of the images I had selected could not be used – this was more than frustrating as they had had the images for several months and said nothing. At that stage I was in the darkroom printing with Dave and they were pulling images out! I was really fed up, as was Dave who had been working hard to get the pictures right. The four problematic photographs were titled as follows: Red machine; Karaoke family; Thirsty family and Pool hall. The first three I really wanted in and the fourth was not such a problem, the email that came included an email trail that I don’t think I was supposed to see as it talked about the “Anna Fox Problem” and about how the image of Butlin’s that I was celebrating was “not the brand”. The Red machine shot I agreed to take out as they did not like the idea of children on gambling machines – I loved the red walls and massive red slot machine. The other two I tried to persuade them to re-consider. Thirsty family is a family of four on a go cart with a cola machine behind them and this one I felt very strongly about and I got it back in – I just could not understand why they wanted it out. The karaoke family they had described, in their list, as the image with the “woman on the mobility scooter in it” – she was the grandmother on her way to bed with hair rollers preparing her for the next day – it was a shame to lose that one. The final prints were framed with bespoke white frames, made by Photo1st, there was no glass and many of the audience at PHG mistook the photographs for paintings – in the visitor book there were numerous comments about the nice paintings and when I gave a talk at the gallery most of the conversation was about how they had been made – people did not recognise them as photographs.

Looking at the history of photography shows at PHG it seemed that there had not been a big colour photography show and most of the photography that had been seen there tended to be classic, small-scale black and white images. The gallery is on the South coast of England and the reaction really illustrated how much of the modern photography scene had been reserved for London eyes only. There is now a book coming out of Resort 1 – published by Schilt in Amsterdam in September/October 2013. Resort 2 is planned for 2014/15 and will be the same format and design.

NF: ‘Zwarte Piet’ seems to be the only series that focuses on traditions and customs from outside the UK. I also know that you have started to produce work in India, tell us more about this shift, your experience and what is next for you.

I suppose when I first saw Zwarte Piet in the Netherlands (staying with my brother in Holland one Christmas) I knew it was vital to photograph him – a white woman blacked up as a Moorish Man, a key character in the Dutch Christmas pageant. The idea was almost directly opposite to what I normally consider good subject matter ( i.e. the everyday) yet despite the bizarreness of this character, Zwarte Piet, he/she was also in a sense quite an ordinary part of the everyday in Holland and the tradition was not well know outside of the Netherlands.

Zwarte Piet is the assistant of Sinta Klaus – Saint Nicholas the patron saint of children originating from either Spain or Turkey. The Dutch celebrate the old fashioned Christmas story more seriously that they celebrate the 25th December Coca-Cola version. Sinta Klaus arrives in every Dutch city, on a big boat, in the middle of November and he is accompanied by hundreds of Zwarte Piets. They parade around the city, Sinta Klaus often on horseback and the Zwarte Piets dance around behind carrying a black baton to threaten the “naughty” children and a sack of cookies for the good ones. Zwarte Piet can change from a clown to a demon in seconds depending on how he feels. Most of the Zwarte Piets are white women blacking up to look like Moorish men though there are some men and some black people who join in too. The story goes that when the Spanish occupied the Netherlands (then the Lowlands) in the 16th and 17th centuries they had Moorish servants and slaves: the Moors acted as the Zwarte Piets for Saint Nicholas – they were his servants. In the book Zwarte Piet, published by Black Dog, Mieke Bal writes and extended essay about this story and about her own desire to be a Zwarte Piet.

I started photographing the first year in a fairly straightforward way in the streets and in shops. My brother Andy and his (then) girlfriend Berit helped me to talk to the Piets and explain that I was a documentary photographer wanting to record them for posterity. There was one school I went into where the background light was very dark, I was shooting quite close up with a wide-angle lens and the Metz flash with a bounce card to soften and spread the light but it was so little light (due to the close up) that the background remained dark with a slight glow from the fluorescent tubes attached to the classroom ceiling – by this time I had sold my first Plaubel and was using a Rolleiflex 6006 with a prism on top so I could use it almost like a 35mm camera. When I processed these films and saw the darker shots I knew these were the ones: They were the most dramatic, less overtly documentary and more similar to paintings – like grand portrait paintings of important people – they were a little underexposed and took a lot of work to print in an analogue darkroom (no problem now with digital editing and light jet printing). Later when Mieke Bal agreed to write about these portraits she pointed out the similarity between them and the portrait of Juan de Pareja by Velasquez – I was amazed and realised how many things we carry in our heads as reference. So after seeing these first few portraits that worked I went back for several more years to take more, it took ages as I really wanted particular expressions. I ended up with 18 portraits that were printed for the exhibition measuring just under a metre square. When hung all the Zwarte Piets stare at you – it is very disarming.

The first solo show of the work was in the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago curated by Natasha Egan. I arrived on the day of the show to find that the pictures had all been taken off the wall and replaced in a third floor boardroom; my Zwarte Piet show had made the board nervous (there had recently been street protests in the US about Kara Walker’s work) they wanted the work locked in the cellar but Natasha had argued that it must be seen. I think the problem was that I (as the photographer) did not seem to be making a judgement about the fact that this blacking up actually took place – this was not conventional documentary practice. I don’t think I could have explained this while I was shooting or printing the work but I do know that when I realised the effect the photographs were having I knew that this was a vital part of the work. Earlier on in the process before Black Dog agreed to publish the work I had had a meeting with another publisher: The editor there, who had been fascinated by the work, suggested I go back and photograph the parades in the street, the boats arriving and the Sinta Klaus character too – like a “proper” documentary. It was a big publishing house and I was very excited by their interest but as I walked away from the meeting I knew that what the editor had suggested was not the project that I wanted to do so I did not go back. In Chicago I was invited to do two talks to public audiences, at one of these a young woman stood up in the audience and said she had been living in the Netherlands for five years and she had never seen a Zwarte Piet and that I had made the whole thing up – then a Dutch person stood up and said “yes it does exist: I was a Zwarte Piet” – it was quite bizarre and I have it on video somewhere.

I first went to India in 1984 during the summer break after my first year at Farnham. I travelled with Jazvinder, an Indian friend from college who had been before, and Freddy, a friend from Chawton House. We flew to Mumbai with PanAm arriving at around 4am in the morning, greeted by the suffocating heat of the monsoon; mud a few inches deep on the road and rats all over. A taxi driver grabbed our luggage before we even got to the exit and we ran to keep up with him, frightened we would lose everything. I was in a ludicrous cotton dress and flimsy sandals, I remember seeing Europeans in sleeping bags lying at the airport entrance, some of them begging, they looked dreadful and I could only assume they were victims of drug abuse. After miles of driving through the main slum areas, in pouring rain, we arrived at a small hotel somewhere central and knocked on the very closed looking door. A massive man dressed in a white loincloth came out and we were ushered into a big room with three beds and shown to a washing room that was an oil drum full of water with a tin can to slosh yourself. I was pretty shocked, Jaz and Freddy seemed fine, the noise of birds and monkeys was deafening, I tried to sleep. In the morning I remember waking up and seeing that half the room was wood panelled – one panel started to move and out came someone who had been sleeping in the cupboard. The cupboards turned out to be the cheap beds and they were completely full. We drove around the city that day trying to find Jaz’s Aunt, who we had a suitcase for (she had left it behind on her last trip to London). The taxi dirver drove all over but we never found the place, we didn’t realise how difficult it was to find places in big Indian cities and so we thought he was cheating us and refused to pay when he eventually dropped as off at the main station. A huge row ensued and we ended up giving him the suitcase full of material bought in London. We travelled on to Agra, New Delhi and Srinagar by bus and train, got very sick (mainly through dehydration) and returned home after about three weeks instead of the three months we had planned. Jaz had gone back after a week as the place was just not how she remembered it and she was hassled from morning till night for the clothes she wore, the haircut she had and the cigarettes she smoked – India in the 1980s was not the place for a liberal young Indian woman to be in, especially back packing. During the journey I started to photograph the dilemmas that arose when rich and poor rubbed up against one another; I took some simple documentary shots that observed the relationship between the new and the old, the tourists and the native Indians and the chaos that existed everywhere. There was plenty of irony to be captured and I had a show of the work, my first ever show, at the West End Gallery in Aldershot in 1985.

In 2005 Sarah Jeans, then an Associate Dean at University for the Creative Arts (UCA) at Farnham, asked me if I would like to go to the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad to investigate a potential collaboration in relation to photography education. I jumped at the chance and set off once again to investigate a continent I had never managed to forget. This was the start of a long term British Council funded project to work together with staff at NID and develop photography education in India coupled with student exchanges and research enquiry. Each time I went to work with NID I booked extra time to shoot new work for myself. I am still developing the projects there, they seem to be quite long term mainly because I find it incredibly difficult as a foreigner to be sure about what I need to say in a body of work. I am interested in the dilemmas that exist in everyday life and particularly in women’s lives, yet this is so hard to comment on without being judgemental and this for me is the underbelly of most documentary practice (to be judgemental) – so I am working through this slowly and perhaps I will eventually work more collaboratively with a writer – I am using a working title, Honour, for the work on women series. I am also developing a body of work called New Age that essentially looks at the clash of new and old, rich and poor, within this fast developing economy.

I have become fascinated by contemporary Indian literature and by the writing of William Dalrymple whose books, Nine Lives and Age of Kali, have inspired the series New Age. In this body of work I have photographed a number of different groups of people and events such as Pulikali and Kumatti Kali in Kerala, the Baul singers and Barupias of West Bengal. I have also started to photograph the Theeyam characters (Kerala) and am about to photograph a group of Hijaras in Tamil Nadu. Eventually I would also like to photograph one of the big cities of widows in the North. All these characters represent change; either through trance (Theeyam) or through men becoming animals/trees (Kummati and Puli Kali) or men becoming women (the Hijaras), men giving up their worldly goods to travel the country as players (Bauls), men becoming cartoon type characters to perform in the street and earn money (Barupias) or women being discarded because they are widows and having to find new communities where they can attempt to survive. Each group represents a different kind of change and change is what seems significant in India right now.

[nggallery id=509]

(All rights reserved. Text @ Niccolo Fano and ASX, Images @ Anna Fox)