One is grateful for The Pond because we are in trouble, and because irony which focuses on the ugliness of man-made juxtapositions does not at this point, by itself, help.

By Robert Adams, excerpt from Creative Camera: 30 Years of Writing (Manchester University Press, 2000)

Irony, defined as unrecognized incongruity, take many forms as a subject for art. John Gossage has in his previous work been alert to several kinds, among them the sort of irony that interested Melville – the disproportion, unacknowledged, of the individual to the world as a whole. One of Gossage’s funnier pictures records, for instance, an ant making its way up a utility pole.

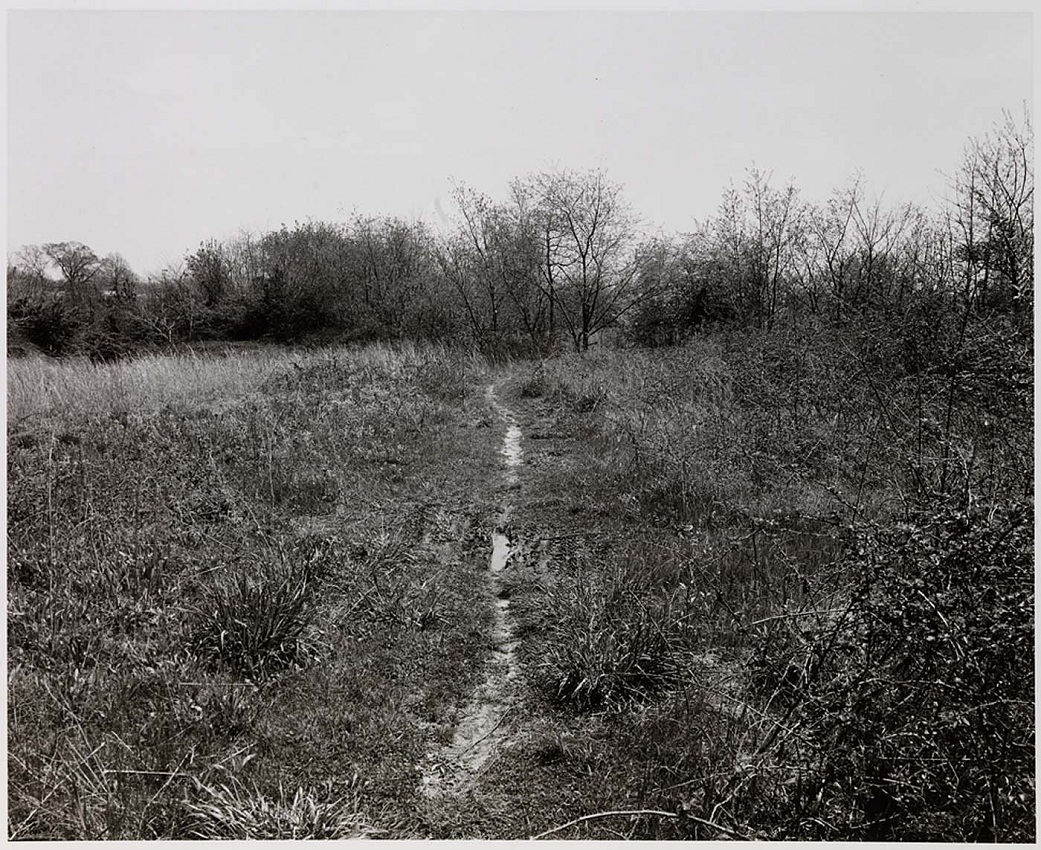

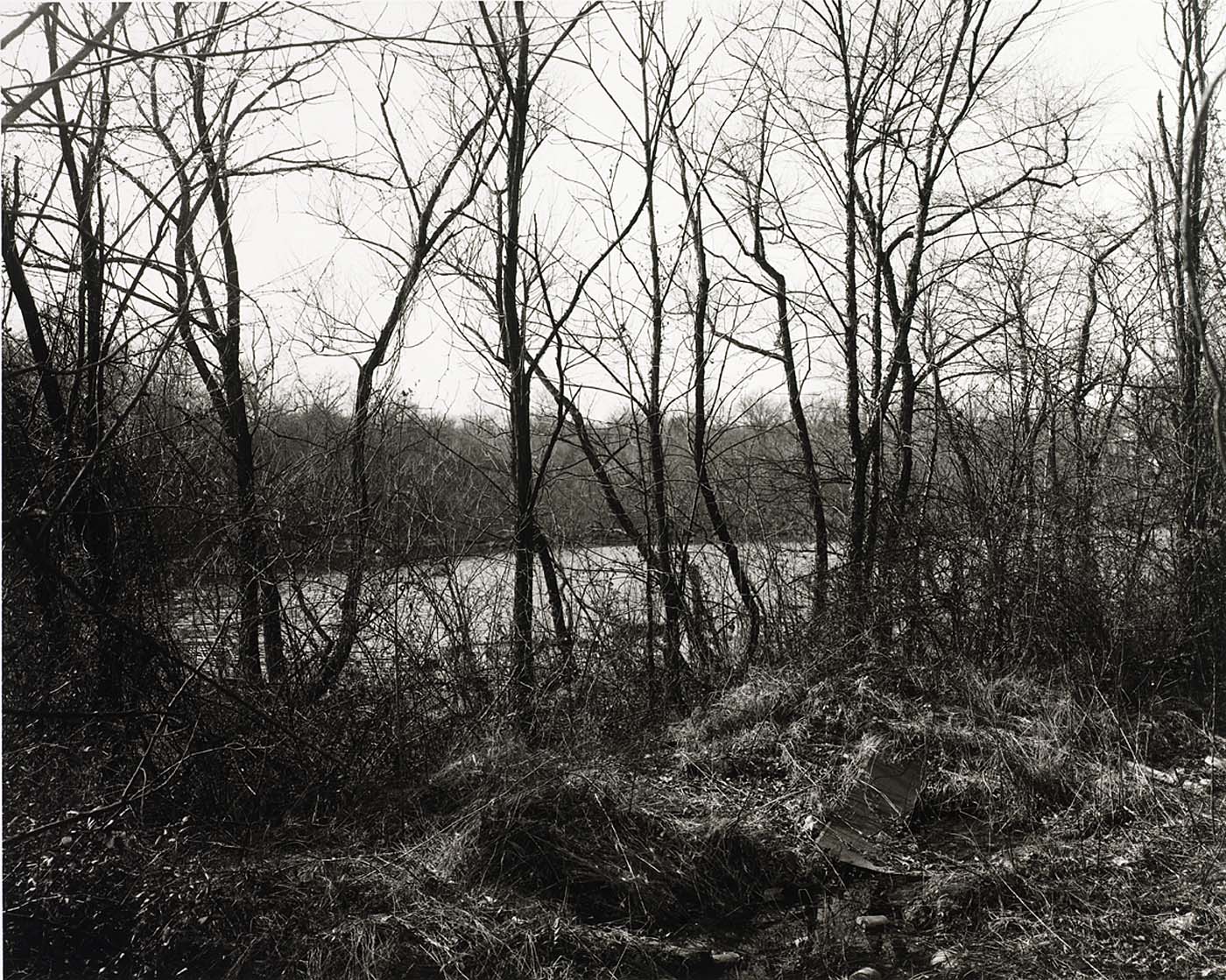

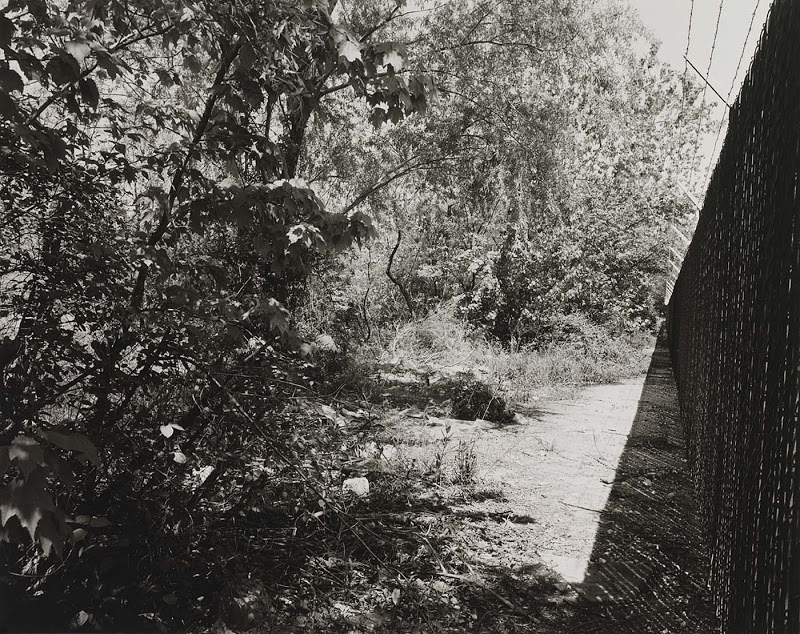

Gossage’s book The Pond, though it implicitly acknowledges such disproportions (and implies they offer consolation rather than humiliation), is fundamentally not about ironies of a lesser sort. Despite his echo of Thoreau, which might seem to promise a didactic pounding, Gossage does not use his survey of wood around a lake to stress an indictment; the off-road landscape through which he leads us is a mixture of the natural one and our junk, but his focus is not so much on the grotesqueries of the collage as on the reassurances of nature’s simplicities.

One is grateful for The Pond because we are in trouble, and because irony which focuses on the ugliness of man-made juxtapositions does not at this point, by itself, help. Americans are the audience (and the protagonists) late in a tragedy; we are not wholly ignorant of our crimes anymore, but we have not yet fully paid for them, and we carry a burden of pity for other and fear for ourselves. And though these emotions are appropriate to the events, they threaten an inappropriate exhaustion. If, as may be the case, we are not to experience the coherence of the end of Act Five in our lifetimes, our effort must be to live with the tragedy unresolved – unjustified, and not fully explained. And for this endurance we need to do something more than rehearse the crimes of the early acts.

Tragedy in its classical literary form is no longer written; authors are unable to find believable resolutions of the plot that can replace our pity and fear with a new understanding, with calm. In a world of unresolved tragedy we thus cast about, and it is the visual arts, it seems to me, that best offer a place of quiet as they remind us of a mystery in the Creation, one that implies coherence but that does not make its way plain. Much of the best work in photography is like the answer from the Whirlwind to Job – a description of natural beauty that implies a higher order.

This is not to suggest that art should only mirror beautiful subjects. Poetry from Whirlwind commands our attention because the story of Job includes, before the consolation of the poetry, an outline for disaster, and it is by that we first recognize our world. It is the incorporation of darkness into art that initially confirms to us, in our discomfort, the importance of art, and assures us that the hope of the art offers has not been cheaply won.

Untitled, from The Pond

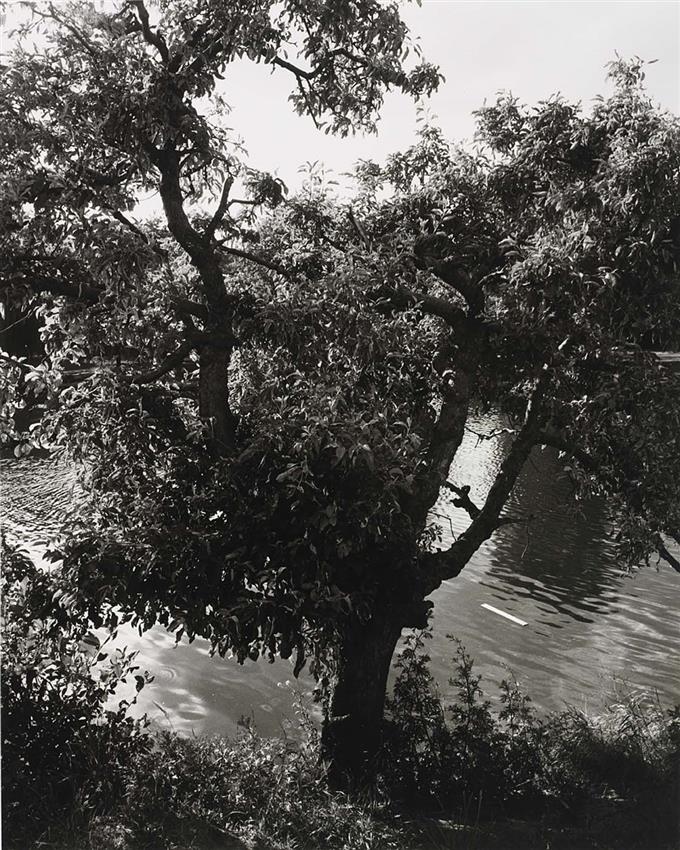

Untitled, from The Pond

Untitled, from The Pond

One of the deficiencies, oddly, with some forms of irony is that it implies an insupportably generous interpretation of the facts. If irony is incongruity unanticipated by those who create it, then the creators are innocent; if they do not know what they are doing, they cannot be responsible. It is a judgement that seems, however, especially when applied to those who now mangle the landscape, dubious. Though one grants innocence to everyone at certain stages in their lives, the sense one gets from the kind and placement of the trash around Gossage’s pond is that it wasn’t necessary to put it there, and the effect of doing so could not have been completely unanticipated; a few of the culprits may have been only willfully ignorant, but most were surely worse – those of us (I think we all do it, with varying degrees of indirection) who disfigure the landscape as a way of striking at life in general. It can be argued, justly, that society has helped people – particularly the poor – hate life, but the fact is that there is one extreme that is impermissible, not matter what the provocation, and that is a hate so unfocused that it takes in everything – the kind of wholesale detestation that is implied, for example, in the breaking of a tree for the pleasure of seeing it broken.

It is the incorporation of darkness into art that initially confirms to us, in our discomfort, the importance of art, and assures us that the hope of the art offers has not been cheaply won.

Such things are, however painful, a necessary, validating inclusion in Gossage’s new book, serving to remind us of the history of the pond, and linking it to the history of all our particular lives.

Though Gossage’s study of nature in America is believable because it includes evidence of man’s darkness of spirit, it is memorable because of the intense fondness he shows for the remains of the natural world. He pictures everything – the loveliness of gravel, of sticks, of scum gleaning the water… He doesn’t even hesitate to photograph what we admire already (which is riskier, it being harder to awaken us to what we think we know), abruptly pointing his camera straight up at circling birds, and, later, over to a songbird on a wire. Nothing is self-conscious about these photographs; we see in them just the subject – and thereby the glory of the common day.

If Gossage wins us by the abandon with which he gives himself to his vision, he strengthens our sympathy for that vision by expressing it through a framework of craft. As an object, for instance, the book is an achievement of the highest order. Reproduction from the original black and white prints is as true as unrelenting care in the application of technology can achieve, and the design of the book, which Gossage worked out with Gabriele Gotz in Berlin, will set standards for years; it breaks conventions successfully (there is no picture on the jacket, for instance, but the jacket effectively invites us to pick up and open the book), and it is full of enlivening complexitites (fold out plates, for example, and unexpected pieces of colour) that have a point and that functions smoothly.

Gossage expands our understanding of his vision, moreover, by developing it within an intellectual and artistic tradition. Which it to say that his work is mature – it makes effective use of the past to bring our attention to the present. When Gossage refers to his predecessors, he not only acknowledges that he learned from them (as does anyone good), but he brings us to liken and contrast his views with theirs, the better to understand his present-day perspective.

Continue reading here:

Creative Camera: Thirty Years of Writing

By David Brittain

Manchester University Press, 2000

Photographs by John Gossage. Text by Gerry Badger, Toby Jurovics.

Aperture, 2010. 108 pp., 52 duotone illustrations, 11¾x11″.

Robert Adams is a photographer and writer. His books include The New West: Landscapes along the Colorado Front Range (Colorado Associate University Press, 1974) and Beauty in Photography: Essays in Defense of Traditional Values (Aperture, 1981).

(All rights reserved. Excerpt @ Robert Adams, Images @ John Gossage)