“But aside from this other kind of intellectual thing of the drawing and writing, I was like into hot rods more than anything else, and girls, obviously, and drinking beer and smoking, all of these things that the pastor’s son is not supposed to do.”

Interviewed by Stephen K. Lehmer

TAPE NUMBER: I, SIDE ONE, MARCH 2, 1996

LEHMER: Your family moves to Riverside in ’46, and in ’49 you attend Riverside [City] College, where you get an A. A. degree in art from ’49 to 51.

HEINECKEN: Even in high school I was in a kind of college preparatory program, but I worked on the yearbook both as a kind of .writer and did drawings and stuff for this high school yearbook and was active in– Oh, you’d have the literature club or drawing club or art– None of these were taught as courses. They were–

LEHMER: Extracurricular.

HEINECKEN: Extracurricular kind of ideas. So again I have, or I had–I don’t know where they are now–sorae writings I had done and a lot of drawings and illustrations, really, for the kinds of things a high school does. But I did take, not in high school but maybe — Certainly in junior college I took formal classes in drawing and things like that.

LEHMER: Well, in high school, if we can back up here just a snitch, what were the courses that began to set or direct your interest? Were they like literature or history or — ? What did you go into? Math and science? Or did you gravitate towards humanities?

HEINECKEN: This is clear in some sense. High school, maybe, the period of time. And in a burg like Riverside it’s not as developed as it would be in bigger cities. But there was one teacher, a woman, who was the literature person.

LEHMER: What was the name of that teacher? Do you remember?

HEINECKEN: Her name?

LEHMER: Yeah.

HEINECKEN: No. I might bring it up sometime if I could, but– She was very enthused about my writing and the combination, I guess, of the writing and the drawing interest. So she was very helpful and supportive and probably in some sense the surrogate kind of mother that a good teacher becomes, like a woman to a young man, young boy.

Anyway, she got me interested in going to college and also actually lined me up for exams or interviews to see if I could go to Pomona College. Pomona College, for those of us who don’t know, it is a wonderful, well-known private school– Very expensive, which I– My memory is that I qualified for– But the scholarship that was offered was like a part, you know, half, maybe, and my parents just couldn’t come up with the money for the rest of it. I don’t think I was aware of how disappointing that– I mean, I could have probably become a CEO [chief executive officer] of a bank somewhere today if I could have gone to Pomona College or something. [laughs] But it’s a very good school. I could have gotten in, but there were some money problems, so I didn’t go there. But it was this teacher who made sure that I had the opportunity to get involved in that. I wish I remembered her name, but-

LEHMER: Do you remember the kind of literature that you read that was meaningful to you in that high school period?

HEINECKEN: No, I don’t, nor do I have any real memory of what was happening in art at that time. It’s like a hick high school, you know?

LEHMER: Right.

HEINECKEN: I think it wasn’t so much of — It must have included that kind of reading, but certainly no study of the history of art or anything like that. But I think she was just enthused by what she perceived to be talents that could be developed along certain lines that were creative, as opposed to mathematics or something like that.

LEHMER: Also what I’m picking up is that you’ve mentioned more of an active role rather than a passive role such as reading, that you mentioned writing versus the reading. You mentioned earlier that you were a voracious reader, but in high school at that kind of a critical point where we begin to see our future, you were actually producing at that point rather– You were writing. You weren’t necessarily reading literature where you don’t remember specific types of literature or books or authors, but you were beginning to– You’re talking about that you’re doing your own writing and drawing. What would be interesting to me is, what did you write about?

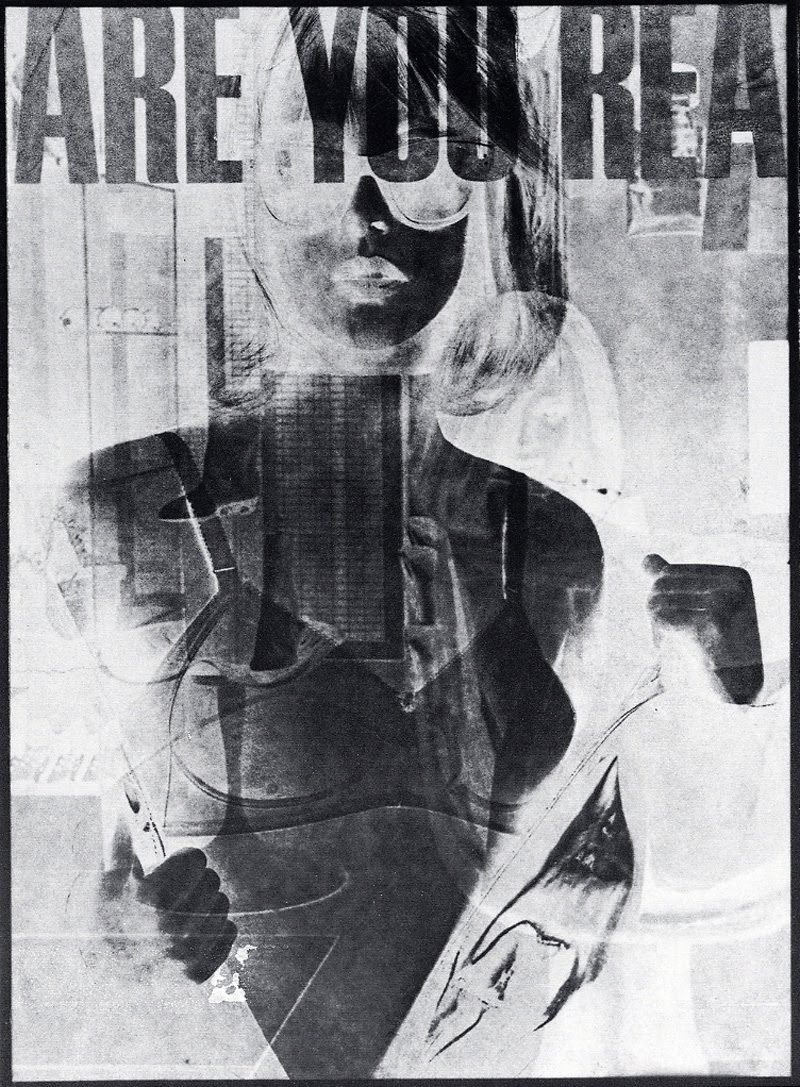

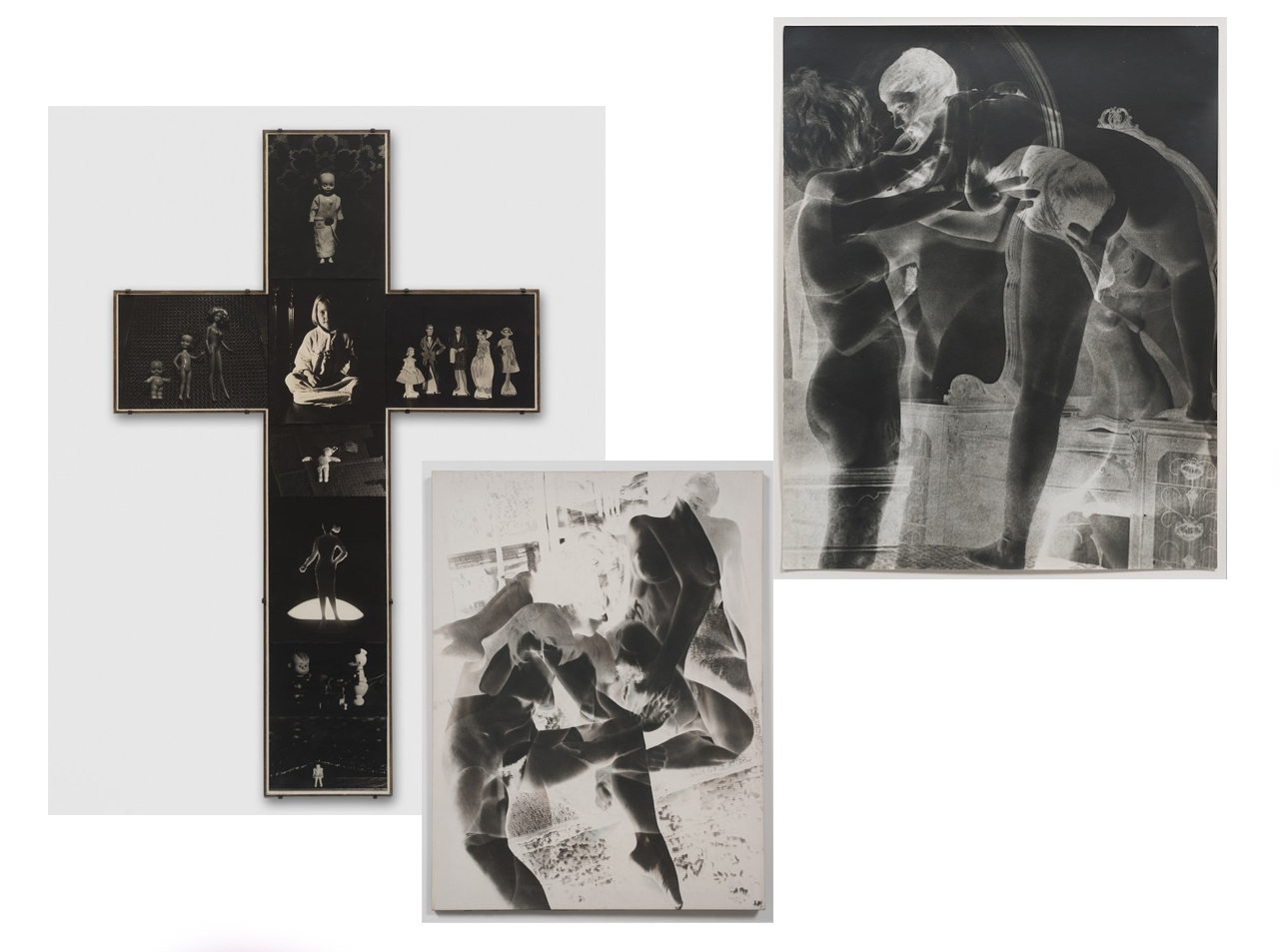

HEINECKEN: It’s very interesting, because my mother through all of this saved everything that I drew. I still have a lot of it. Some of it’s pretty advanced, and some is garbage and stuff like that. But the writings were never saved . I don ‘ t think she saw the importance of that, or maybe she was simply focused in the other direction, maybe because of my grandfather’s interest in art or something like that. And maybe in a sense my gift, if that’s what we can call it, was more for the visual thing than it would be for writing. I remember writing. I remember being in these exhibitions of drawings. You’d have readings by students; I was involved in that. I do remember that. By I have no evidence of what that was, and I don’t remember it. I don’t think it was poetry. It was probably- -what would we call that?–like “This is what I did for my summer vacation” or something. But in fact, at this point, and even in the evolution of my artwork, the what I would call a kind of literature aspect–that is to say the titling, the writing, the reference to writing, to language- -in the pictures is very strong. Probably that ‘ s the only thing that you could trace that would be constant through all of it. It’s not a visual art per se. It’s an ideational art based on language principles, based on metaphors, simile, parody, all these things that arereally literature ideas. We can talk about that more, but–

“I went drinking beer probably or something like that. It wasn’t a serious thing, but it– You know, when the minister has to go down to get the minister’s son out of jail, it’s not exactly what you want to do.”

LEHMER: So that’s in high school?

HEINECKEN: Yeah. And also I was very rebellious, which is the other side of this time period. I didn’t want to leave Los Angeles. I had just entered high school, I guess. And probably the freedom of living with this other family was good. I had this very good friend who was the guy who actually went on to become an Olympic hurdler. I forget his name right now. So I was not without– I mean, I was without my parents, but had this surrogate family. But it was very good for me to do that, because– And I didn’t want to go to Riverside. They were insisting, “Well, you have to come to Riverside. You finished that school. Now you’re coming.” So I went, but very– I went because they told me to go, but I didn’t like it. It was a hick town. I was from Los Angeles, you know, all of that. But I went. I had a very difficult time with my family regarding the church. My father was very tolerant because of his background. I mean, he wasn’t going to come down on anybody simply because they were rebellious. [laughs] He knew about that. But finally, I remember very clearly at some point, I went to jail once, for which he had to come and bail me out.

LEHMER: What was that for? Do you remember?

HEINECKEN: I went drinking beer probably or something like that. It wasn’t a serious thing, but it– You know, when the minister has to go down to get the minister’s son out of jail, it’s not exactly what you want to do. But anyway, I don’t know whether it was the direct result of that, but I remember having a conversation with him which really came down to, “You can do whatever you want to do. I’m not going to tell you what to do. But you do have an obligation to my profession, which is ministry, so you will be in Sunday school, and you will be in church every Sunday. I don’t care if you stay up till five o’clock Saturday night drinking beer, you will be there on Sunday morning. And that’s our deal,” he said. And I said, “Well, this is okay.” I could sleep through Sunday school, church, whatever. “I’ll be there” as a kind of symbol. Because he said, “If you’re not there, how am I supposed to convince these people that their children should be here?” And I understood. So it was an agreement between us that was, as I think back– I would have never been that gracious or that understanding with my kids. I just wasn’t– I didn’t have that capacity. And my kids rebelled. I guess all kids rebel. But aside from this other kind of intellectual thing of the drawing and writing, I was like into hot rods more than anything else, and girls, obviously, and drinking beer and smoking, all of these things that the pastor’s son is not supposed to do. Obviously I did it because I resented something about the whole thing.

LEHMER: And that rebellion is an interesting idea. I’ve always been intrigued by what you are rebelling against. Are you trying to establish your own identity or express your own ideas? You’re maturing, and you want to consider who you are versus who your family is. It sounds like you had a strong family. They were strong enough to be actively involved with other people’s lives, trying to influence other people’s lives, so they’re obviously going to be doing that with you. And at some point you’re trying to establish your own identity, I would imagine.

HEINECKEN: Well, I didn’t know all the history of the family when this was going on. I mean, I know that now, and I’ve accumulated all this. But what strikes me about it as being very clear is that this is a man who made a big mistake with this woman, got himself in trouble with the church, lost his job, lost his profession, but decided somehow to go — Well, first of all, to go back to school when he was a kid to start this whole thing, and then even after making this horrendous mistake went back again, because he finally got it figured out for himself. It wasn’t necessarily just the religion of it but the morality of it, I think, or something. So he clearly saw in me some kind of replica of his running away. I mean, I never ran away, but in a sense running away from appropriate- –

But I liked his deal, which was, “I’ve got my life figured out, I’m going to be a minister, and you are going to conform to the extent that you will not damage my situation.” I thought, “Well, this is — ” Again, I’m remembering. I’m not remembering it verbatim, but this is an important thing, to have an understanding with your father that this is the deal. “And you will do it that way.” And of course, for me it wasn’t a bad deal. All I had to do was show up. I didn’t have to believe that or anything. And I’m not sure where my mother was in any of this. She doesn’t seem to enter the picture on this. This was a deal or an understanding that was made. But he was very tolerant. So was she.

I remember when I finally had a room of my own. It was covered with these pretty girls and [Alberto] Vargas girls, which passed for erotic pictures for a kid. [laughs] And then there was no objection on their part that this was there. It was private. That was my room. I can do whatever I want–masturbate, whatever– Whew, right? And I think I still have a streak of– I mean, I know what’s right and wrong, and I try to do what I think is right. I’m not perfect at it, certainly, and I’ve made a lot of mistakes myself. But I do have a morality which is not based in formal religion necessarily, but it comes out of that religion, that there are some rules, right? There are the Ten Commandments and things like that which you can adhere to, or try to, without becoming religious or something.

LEHMER: You have learned through your environment, through direct teachings from your parents, but did you ever feel like you wanted to rebel against that? Or was it just that–? Have you ever been able to identify what you did in high school? Some people I think pursue activities at that age in direct rebellion against their parents. Other times they’re beginning to figure out what it is that they really want to do on their own. Or you know what’s right, but — Were you tempted to do what you knew was wrong for the thrill of it?

HEINECKEN: Oh, I think this is true then and now and forever, that the environment of– Or being an adolescent, the environment of that culture in that school is the strongest thing there. I mean, the thing about peer pressure is, of course, true. I forget my point, but I had figured out somehow, not consciously necessarily– At an early age I knew how to do school. Some people know that. Some people never– It doesn’t have anything to do with intelligence. It’s just like I could do all of my homework in study hall. I never had homework to do. I just figured out how to do that. So I wasn’t a bad student or anything. But again, this high school is so hick, you know. There aren’t any bad students in this. They just show up or whatever. I got grades good enough, as I said, to apply to this program, and certainly as a result I– The summer I graduated I went to UCLA on a summer thing, which was to introduce you to university life for three months or whatever. Then you would —

TAPE NUMBER: I, SIDE TWO MARCH 2, 1996

HEINECKEN: So I was saying that I went to UCLA during the summer of 1949. That would have been to participate in the program which– We actually took courses. I forget what I took, but I maybe can remember that. But it was really to give you an opportunity to transition from high school–no matter what kind of high school it was–into that situation. So they put us up somewhere. I can’t remember. It was like a dorm kind of situation, so that was controlled. I don’t know if they still do this or not, but they would meet you, you know– Other students would– In other words, it was like a program to acclimate you to this life, because it’s so different from what your previous life was about. And we took courses, but– And I can’t remember what I took, but the point is that at the end of that three months, or maybe even before that, I had completely kind of washed out of this deal because I could not handle it. I mean, I was just too young or too immature, too mixed up or whatever. But in a sense what I did was fail this summer school kind of thing, which was a big disappointment, because this was my big move from, well, high school to college, or in this case university. I had been accepted, which was no problem, because of the grades and whatever. But I guess emotionally or something I just wasn’t ready for it. So that was a big disappointment.

“Well, for me, it’s a horrible thing to say, but I think I could probably do without most of the things that I have. I’d get by. I mean if Joy [spouse] died it would be awful, but I’d get by. I mean, I adapt to things.”

At the end of this, or whenever I dropped out of it or flunked out of it, I went back to Riverside and enrolled in the community college–then called junior college — called Riverside College, which was a two-year basically vocational kind of school. But the lower- division college courses were all taught that would be transferable into university programs. 1 went back and did that. And I think I lived at home, basically. But there was a small group– I know I lived at home, basically, but there was this other place, which was an apartment or something like that, where similar people like myself lived. And this was now 1950, right? Or 1949.

LEHMER: Yeah, 1949-50, when you were at Riverside College.

HEINECKEN: Right. Okay. So the Korean War happens in 1950. Oh, meanwhile, I should mention, in this junior college were still probably the last vestiges of the World War II veterans. So it was interesting, because you had in that age group people who had real experiences with that war along with eighteen-, nineteen-year-old kids. And it was really a schism between– I mean, these guys

were serious and older and had that aura of, like, veterans. And then you had the regular kids, like the idiots who were much younger and with no experiences. So it was initially an educational problem–not a problem for me — to try to figure out how to deal with these mature people as opposed to these beer drinking people. Anyway, toss it aside.

So I did the two years there basically with the idea of taking lower-division academic courses to transfer to UCLA as a junior–right?–but also continued because I was going to major in art when I got to UCLA or anyplace.

LEHMER: So that was your intention even then, to go to UCLA?

HEINECKEN: Yeah. Well, someplace. UCLA was obviously the major university at that point in the UC [University of California] system for Southern California. The other schools didn’t exist. And I guess it would have been the only public university other than maybe some state colleges or– Anyway, that’s where I had decided to go.

But I took courses also in this junior college in art, like painting, finally something like that rather than drawing and illustration, basically. But it wasn’t a program that introduced me very well into what I experienced in the art department at UCLA when I got there. It was more like still a second-class– Well, really like an illustration kind of an idea or something that could be applied art, design, something like that, and drawing not as an expressive or painting as an expressive idea but as a kind of skill, a kind of craft, a kind of — You know, how to make something look like it should look. I have a lot of paintings and drawings from that period of time, which are kind of — There is some skill there, but they’re not exceptional. Anyway, I had like almost straight A’s out of this two-year experience and still continued to– Most of my time was spent like with the car culture and something. I wasn’t a student necessarily. But it was easy for me still. I just knew how to do that somehow.

I forgot to mention that I met my wife Janet — Storey was her maiden name- -in high school.

LEHMER: In high school?

HEINECKEN: Yeah. She was one of those women or girls, I guess you’d say, in high school who was part of the elite kind of group. There’s always that group of like cheerleaders, although she didn’t do that, I don’t think. But they were all the good-looking girls, and they were lively and so on. So she was really one of those girls. We dated rather consistently — maybe we went steady, I

can’t remember- -through high school or the last of high school. Then, when she graduated, she went into nursing school in Los Angeles, so that sort of ended our whatever was going on. Except I would date her. I mean, I would come into L.A., or when she was in Riverside we would go out and whatever. And we were in love. I mean, it was that kind of thing. But it was that she was in L.A. and I was back — I think that was probably what was disappointing about not getting into UCLA the first time, because she was in L.A. And we would have probably continued that relationship, which then became sort of less involved. Anyway, I was dating other people, she was, and so on. But that’s how I met her. Later we’ll talk about that, how and when we were married or whatever. So we’ll try and maybe find a place to stop here which would kind of be easy to pick up on when we start again. Anyway, I’m graduated from this junior college. I’m going to transfer to UCLA and take up that life. So maybe we can stop at this point and pick it up at that juncture, if that’s useful for you.

LEHMER: Okay.

HEINECKEN: There are probably things that will come to my mind about this time period that we haven’t talked about, but —

LEHMER: Maybe we can pick that up right at the beginning of—

HEINECKEN: Yeah. Or if you listen to it and see if there are some gaps or whatever, because- –

LEHMER: I’m sure I’ll have some questions, and we can fill in things.

HEINECKEN: The only thing here that I thought was interesting is that as a kid– Did anything stand out? And I was trying to think about that. The only thing that comes to my mind is the kind of independence or something that maybe comes from my parents or from the situation of living apart from my father, thinking he was part of this giant, wonderful military thing when in fact he wasn’t, and that they were divorced and they didn’t tell me. I don’t know. These are kinds of things that I think probably at the time I didn’t realize but later I kind of thought something was wrong there, or there was some– I don’t think it would be uncommon, let’s say, especially during the war, that you wouldn’t necessarily feel obligated to tell a kid seven or eight years old that you’re divorced. I mean, why not spare him that? But in retrospect it just seemed like a kind of — I didn’t want to have to hear that from this maiden aunt. I needed to hear it from them.

LEHMER: You mentioned, I think it was in Glendale, you lived with a friend. You lived with a family whose son was a very close friend of yours.

HEINECKEN: Jack Davis. That was his name. That just popped into my mind.

LEHMER: Jack Davis. Well, maybe you can think about it, but I’m curious about other friends you had and what kind of relationships you had with them and what you did. HEINECKEN: The implication here, which — I never said it. I mean, I’m an only child. I think for me that breeds a kind of independence and also takes away any opportunity to use brothers and sisters as a familial device or– You know, brothers and sisters enjoy something that no one else who doesn’t have them ever gets. And I don’t think I miss that, but I think it makes you self -centered. In my case, I think reading and fantasizing about reading– fantasizing about everything and constructing your own internal world–can be beneficial, but it also isolates you from– I mean, I think basically you’re a colder person, because you don’t grow up with the sense of — And I had cousins or whatever, but I never saw them or anything. So that’s important. If anything would stand out, it’s that kind of notion. I don’t know how to express it more clearly, but–

LEHMER: A form of survival based on independence or a form of independence based on–

HEINECKEN: Well, for me, it’s a horrible thing to say, but I think I could probably do without most of the things that I have. I’d get by. I mean if Joy [Joyce Neimanas] died it would be awful, but I’d get by. I mean, I adapt to things.

My whole childhood, the period of time with my mother in Iowa without my father and with this familial problem, I remember being just completely in my own world most of the time. I had these soldiers. I would recreate whatever the current World War II stuff going on was. I was just absolutely focused on the order and the — These soldiers had to be the same scale. In other words, if I

got a soldier that wasn’t in scale, it would not work. I mean, that soldier was gone — right? — because it throws the whole thing out of kilter. I’m very much like that now, as you know. Things are on the surface very disorganized, as is my mind, but underneath that is this acute sense of–

LEHMER: Order.

HEINECKEN: –order and obsession with not knowing where all — Well, knowing where all these pictures are and who has them is a very unusual kind of obsession. I mean, most people– Like I was talking with Robert Frank last night about something like this, and he has no idea where these pictures– Nor does he give a shit where they are [laughs], which is quite different than my– And I think it’s a kind of — When you say that, it’s an admission of not guilt, it’s an admission of a weakness in relation to what you make. It’s as if they’re your children and you want to know where they are. But that’s silly. But that’s the way I am .

Completed under the auspices of the Oral History Program University of California Los Angeles

ASX CHANNEL: ROBERT HEINECKEN

(All rights reserved. Copyright © 1998, The Regents of the University of California)