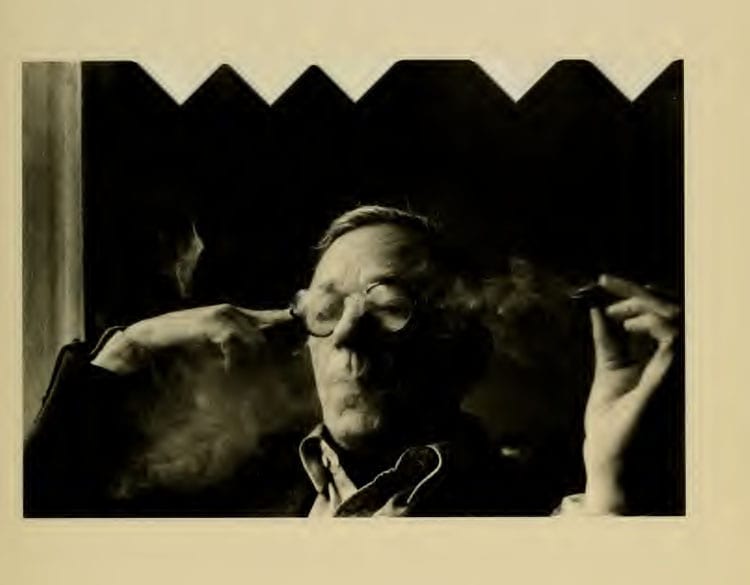

“Photography is a system of picture making in which subject and form are identical and indistinguishable, in which the subject and the picture are beyond argument the same thing.”

Evening Lecture

I would like to address myself to what may seem to be a positively primitive question, and consider in an exploratory way the manner in which photography has changed our understanding of the idea of pictorial subject. The fact of the matter, if we are to begin on the basis of full and open disclosure, is that those of us who have thought about photography have not yet made a great deal of progress. Even in terms of historical matters, our knowledge is shot full of ifs and buts, erasures, illegible words, missing chapters, and dubious conjectures. Perhaps we should start back at the beginning and consider the relationship in photography of subject and form.

Photography is a system of picture making in which subject and form are identical and indistinguishable, in which the subject and the picture are beyond argument the same thing. But what interests me most about this would be a corollary which states that the function of the photographer is to decide what his subject is. I mean that this is his only function.

The kinds of choices that a photographer makes in the process of defining his subject cover a broad spectrum, ranging from gross choices to exquisitely subtle ones. Beginning on the gross end, the photographer must decide whether he will work in his own backyard or sail off to Egypt or to the moon. Once in Egypt, he has to decide whether to photograph Egyptians or pyramids. From this point on, the decisions become not more important, but subtler: which pyramid? from what vantage point and in what light? in what relation to the picture frame? with what combination of exposure and development in order to achieve a just resolution of the conflicting claims of surface texture, space, volume, and pattern? and then the decisions bearing on the making of a print that will most closely approximate the slippery memory of that true and ephemeral subject that was defined on the site.

British landscape, Marine Park, Southport, England, by Francis Frith. ca. 1880.

“The history of photography as a radical picture making system, can be defined as the history of the definition of new subjects. Sometimes these new subjects are extensions of ideas that exist in latent form in the work of exceptional photographers of an earlier generation. Sometimes they are genuinely primitive ideas mothered by a new technical breakthrough or a new market demand.”

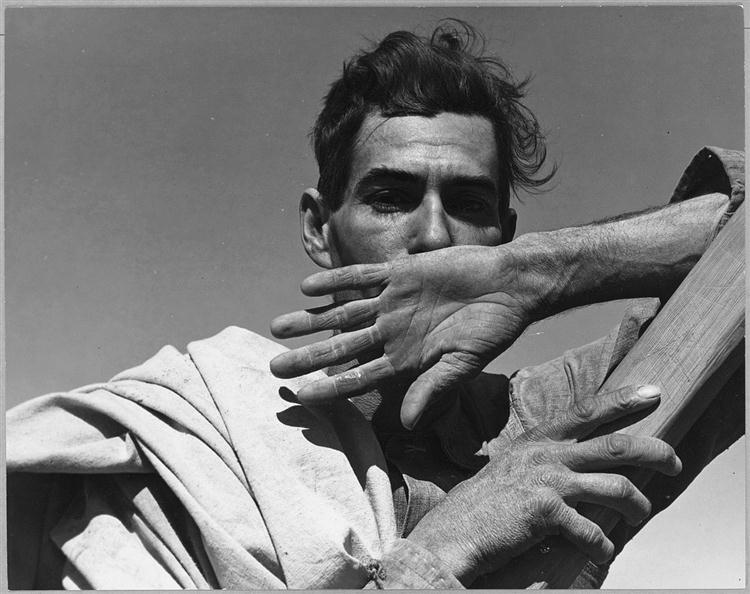

The degree of complexity that separates the decisions of Francis Frith from those of Dorothea Lange, photographing a cotton picker in Eloy, Arizona, almost a century later, is obvious enough. But I think the principle is the same. Choice, intuition, and the winds of chance took Lange to Arizona. By passing a million other potential subjects, she found her way to this particular plantation. There she chose to ignore the landscape, architecture, the beautiful intricate machinery, in order to concentrate on the men who worked there. Among these she chose to photograph a group that included this man. She made several exposures of him and his fellow laborers from a distance as they loaded their cotton. She then decided that she was not yet finished; and she moved closer, homing in on this man, perhaps because he had a good face, more likely, I think, because he was in a good light. By this point, the question of what the subject is involves choices in four dimensions which must be coordinated swiftly and intuitively.

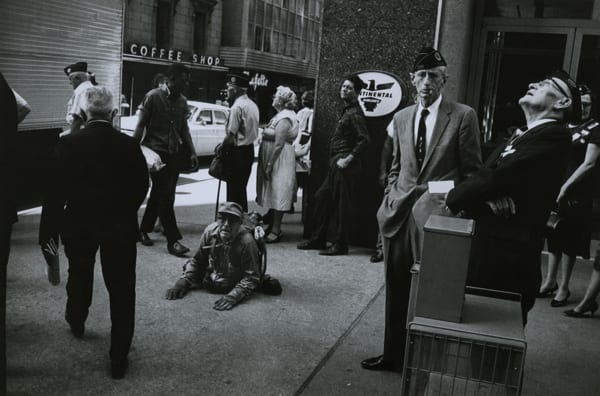

Dallas, 1965 by Garry Winogrand

“The kinds of choices that a photographer makes in the process of defining his subject cover a broad spectrum, ranging from gross choices to exquisitely subtle ones.”

If Lange’s picture would have been inconceivable to Francis Frith, I think this picture, this subject, by Garry Winogrand would have been almost as startling to Lange. For while her subject might have been at least approximately preconceived in verbal terms, the Winogrand picture depends on the recognition of coherence in the confluence of forms and signs that could not, I think, have been anticipated by the most fertile imagination. This coherence cannot, in fact, be understood in analytical terms while the photographer is working. At this level of complexity, intelligence must become-visceral. The history of photography as a radical picture making system, can be defined as the history of the definition of new subjects. Sometimes these new subjects are extensions of ideas that exist in latent form in the work of exceptional photographers of an earlier generation. Sometimes they are genuinely primitive ideas mothered by a new technical breakthrough or a new market demand. But in either case, the picture’s new meaning and its new appearance are the same. I would like now to show you examples from three bodies of work, very different in their motivation and appearance. I’ll ask you to judge for yourselves whether or not their content is separable from their aspect. I will show you a group of classical newspaper photographs, some pictures by the great French photographer, Eugene Atget, and some recent photo postcards by a young American photographer named Bill Dane.

Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona, 1940 by Dorothea Lange

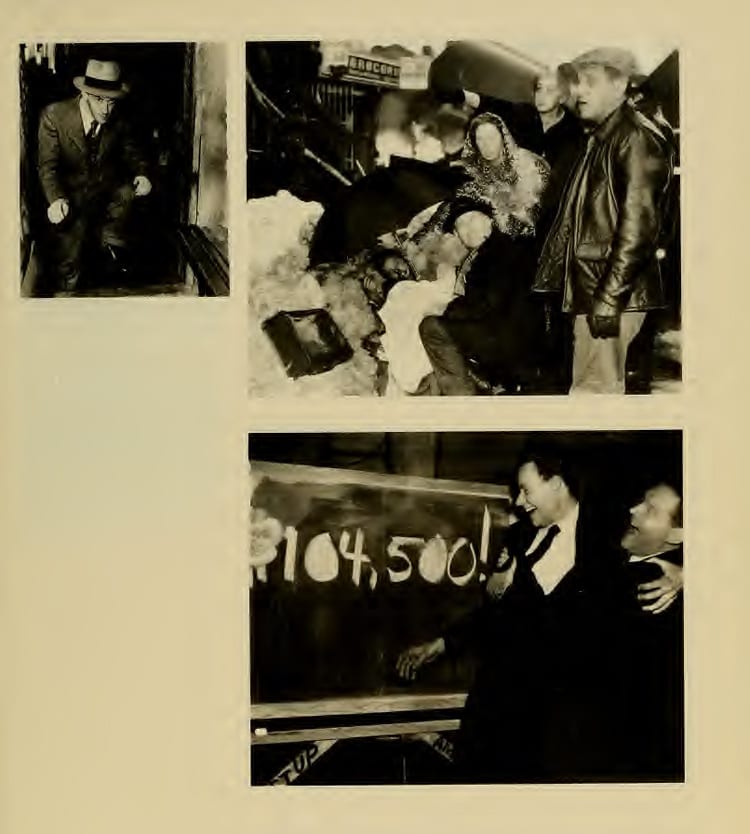

“One of the great charms of early news photographs is that one can’t tell which ones are posed and which ones are not.”

News photographs might well be an especially rewarding area for one wishing to study photography in its most basic and unadorned form. Perhaps the reason why this has not been done is that there has been considerable doubt as to whether or not these pictures are really art. If it were possible to avoid this question, I would of course much prefer to, simply because it is not the most interesting or the most useful question. But since it is probably not possible to avoid it, let me answer it quickly and say, “Yes, of course they are art.” Not terribly fine art, perhaps, but then fineness is not the only artistic virtue.

Before attempting to define what their subject matter is, we should first clear the air of certain misconceptions by defining what it is not. The subject of news photographs is not news. The simplest way of demonstrating this once and for all would be to persuade a newspaper publisher to reprint, one year after their original appearance, all of the photographs of one year earlier, with slightly varied captions. I don’t really think anyone would notice the difference. I do not mean to suggest that newspaper photographs within more or less standardized categories are identical. On the contrary, they are no more identical than the visitations, annunciations, nativities, crucifixions, depositions, resurrections, and assumptions of fifteenth century Italian paintings. News photographs are, however, similar from day to day and year to year, and it is partly in this similarity that their interest lies. A social historian or an anthropologist could surely find much to interest him in the structure and cultural meaning of news photographs, but my own interest is a good deal more modest. I am interested in their character as pictures, by which I mean their iconographic as well as their graphic patterns.

I would like now to suggest several formal characteristics that seem proper to the entire genre and consider them briefly one by one. The pictures are possessed of great narrative ambiguity: without the caption one is never quite sure what is happening. They are hierarchical and formal: what information comes from the picture itself is given within the confines of a rigidly conventionalized technique. They are fragmentary and symbolic: most news photographs are, in one sense or another, close-ups that do not pretend to describe context. They are in large part ceremonial: they deal with events that would not have occurred had they not been newsworthy.

First, these pictures are identified by great narrative ambiguity. Look at this picture (below) and decide for yourself what specific drama is being played out. The young woman on the right is the daughter of the gentleman on the left who has j ust confessed to murdering his wife, the girl’s mother. Or, he is the father of the girl’s late lover whom she has just shot. Or, he is the detective who has just arrested her on the charge of possessing a gun without a license. Or perhaps the gun has nothing to do with the case, but was left there by the policeman who lent his desk to the distinguished family solicitor on the left. Or perhaps the photographer put the gun there to make it a better picture. I apologize for not being able to tell you which, if any, of these stories is true. We did try, but no one seems to remember what the picture was once supposed to have meant. It is a picture that describes the smell and texture of bad trouble and personal tragedy. Its concern is not history, but poetry.

Ed Morgan, Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, undated

“These pictures are not natural, but formal. Their true content is determined largely by the photographic and journalistic disciplines that create them; or to put it more simply, their function follows their form.”

These pictures are not natural, but formal. Their true content is determined largely by the photographic and journalistic disciplines that create them; or to put it more simply, their function follows their form. For example, a classic news photograph describes an event that takes place in a flat and shallow space about twelve feet in front of the camera. This plane is determined not, of course, by the objective nature of historical events, but by the preferences of photographers’ equipment, the limitations of newspaper reproduction, and the pace

at which the photographer works, all of which encourage trust in tried and true formulas.

These pictures are fragmentary and symbolic. Sometimes they are symbolic of genuinely significant events; much more often they symbolize conditions of life that are no more newsworthy than tears. The generic morals of these pictures are generally simple to the point of banality; but the pictures themselves are not banal, for each retells the silly old story with a slightly different set of specifics, a different texture of feeling, a different unique face, a new gesture. No two felons cower quite the same; every detective wears his superiority with a slightly different style; the ubiquitous greedy spectator is unendingly fascinating. In the best of these pictures these various signs and symbols come together with perfect economy and surprise to create not merely a catalogue of visual description, but a picture.

Most of these photographs are ceremonial. A good share of them are frankly ceremonial, by which I mean that the ceremony would have occurred in approximately the same form even if photographers had not been there to publicize it, as illustrated by baseball games, prize fights, and courtroom trials. Other kinds of events, once extemporized according to the logical requirements of the event itself, are now planned according to the requirements of photography. Most news is managed news. Generally, however, the news is managed not to conform to a philosophical or a political standard so much as it is managed to conform to the requirements of the techniques by which one reports it. In our literate past, many events, doubtless, were arranged or rearranged so that they might be written about by the poet laureate or the court historian. Today events occur so that they can be photographed.

One of the great charms of early news photographs is that one can’t tell which ones are posed and which ones are not. This picture is clearly posed.* The personae have been rearranged to fit more economically within the frame of the picture. Later on it becomes more difficult to tell which pictures are arranged, or at what point in history they are arranged. The sincerity of this picture, to me, is simply beyond challenge. The surprise and delight of the contestant and the sympathetic joy of the TV host at the contestant’s miraculously correct answer to the unanswerable $104,500 question are not open to doubt. Even after having been told that Mr. Van Doren’s encyclopedic knowledge was assisted by a little judicious prompting, we do not really disbelieve the evidence of the picture. I have been trying to persuade you that the subjects of news photographs are precisely what they appear to be, and that it is only the captions and the editorial page that have made us believe otherwise.

The gulf that separates a photographer like Arthur Fellig, known as Weegee, perhaps the greatest of all news photographers, from a photographer like Eugene Atget, who was perhaps simply the best of all photographers, is a gulf that separates a great natural talent from a profound, original intelligence. Since Atget did not himself write manifestos, it is assumed that he was a talented primitive who wandered aimlessly through Paris, intuitively making wonderful pictures which were beyond his own comprehension. The pictures themselves, some 3000 of which are now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, do not support this view. They suggest, on the contrary, a man who understood that photography could be a precise, critical tool, a system with which an artist could define exactly what he thought to be true.

Clockwise: John J. Reidy, Murderer Steps into Patrol Wagon, New York Daily Mirror, undated; Paul Bernius, Stephen Baltz, 11, of Willmette, Illinois, lies critically injured on Seventh Avenue, near Sterling Place, Brooklyn. He was the sole survivor in a two plane collision which claimed more than 130 lives in the worst air tragedy in New York City, New York Daily News, 17 December 1960.; Photographer unknown, Charles Van Doren Winning $104,500 on the T.V. quiz show, “Twenty-One,” UPI, 21 January 1959.

The general and encompassing theme of Atget’s work was his own visual life. As an adopted Parisian who loved his city, his visual life was inextricably intertwined with Paris and with his deep appreciation of the fruits of traditional French culture. But he knew the difference between an idea and a sentiment. He knew that while Paris was his arena, his subject was precisely what he defined within the 7×9 inches of his little pictures.

Atget often made more than one picture of the same subject.* He returned again and again to the trees of St. Cloud and Versailles because he knew that an infinite number of beautiful pictures were potential in them. And he knew also that none of these images was true in the sense that it shared a privileged identity with the object photographed. He did not confuse the subject with the object; he understood that the true subject is defined by the picture. If the tree is the same, the subject is always different.

Atget was concerned with complexity and the relativity of form. The breadth of his interests reminds us of the Encyclopedists of the Enlightenment, but the quality of his sensibility seems prophetically modern. The perspectives of his mind were Copernican rather than Platonic; he worked not from, but toward a formal idea. His conception of form was not nuclear, but galactic, relative, plural, dynamic, provisional, and potential.

Four or five years ago, a young California painter named Bill Dane discovered photography and instantly set out to practice it with enormous enthusiasm and generosity. The generosity expressed itself in the form of a massive barrage of photographic postcards which he sent without obligation and, I suspect, often without acknowledgment, to what would seem to be an enormous mailing list. This is not the manner in which artists have traditionally subsidized their public; so it is perhaps not surprising that when a few critics did begin to take cognizance of Dane’s work, they tended to be more interested in the fact of the postcards than in the pictures that they carried. But the real reason that I like Dane’s postcards is the fact that they have, I think, beautiful pictures on them, pictures that define new subjects. It seems to me that the subject of Bill Dane’s pictures is the discovery of lyric beauty in Oakland, or the discovery of surprise and delight in what we had been told was a wasteland of boredom, the discovery of classical measure in the heart of God’s own junkyard, the discovery of a kind of optimism, still available at least to the eye.

The trouble and the good part is that these new subjects are defined in visual terms, and no matter how patiently we thumb through our thesauruses, we will not quite reconstruct them with words. The same thing is, of course, true of the news pictures and of those by Atget; but in those cases, at a slightly greater historical remove, it is easier to pay the pictures the compliment of affectionate and knowing gossip. Much of the content of these pictures is concerned, I think, with a kind of visual play, and therefore with agility, surprise, balance, unexpected moves, and grace. The subjects of the pictures are these virtues in themselves, and also the fact that these virtues can flower in such unlikely circumstances. At first acquaintance, the pictures might seem casual. I believe, on the contrary, that their very point and purpose is order. Like much of the best photography being done today, they concern photography’s ability to know and rationalize reaches of our visual life that are so subtle, fugitive, and intuitive that until now they have been undefinable and unshareable.