“There was also a clause in the Criminal Code which banned the distribution of nudity in photographs, so it put off most photographers from approach this theme.”

Nikolay Bakharev in Conversation with Luca Desienna of Gomma Magazine – Translation by Olga Ippolitova – Series Baharevland

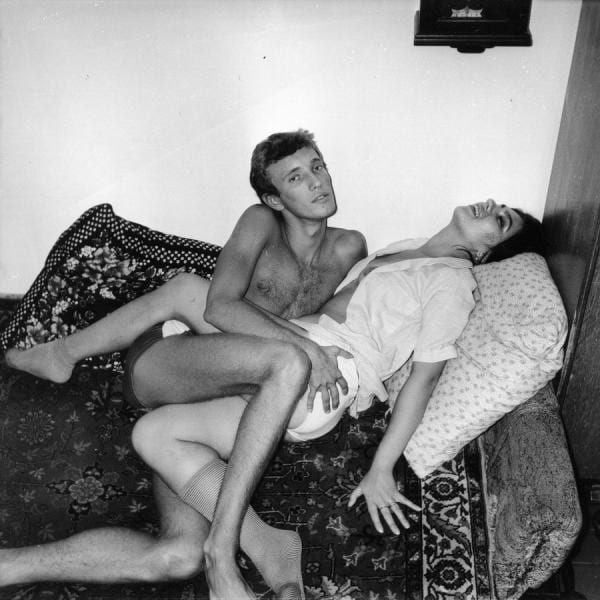

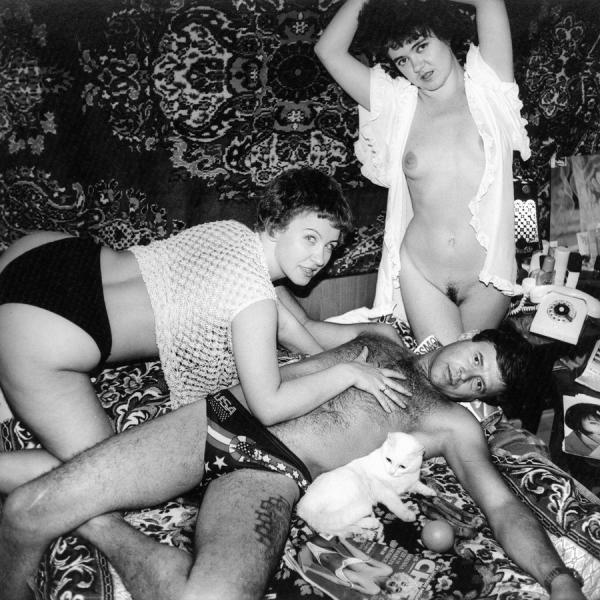

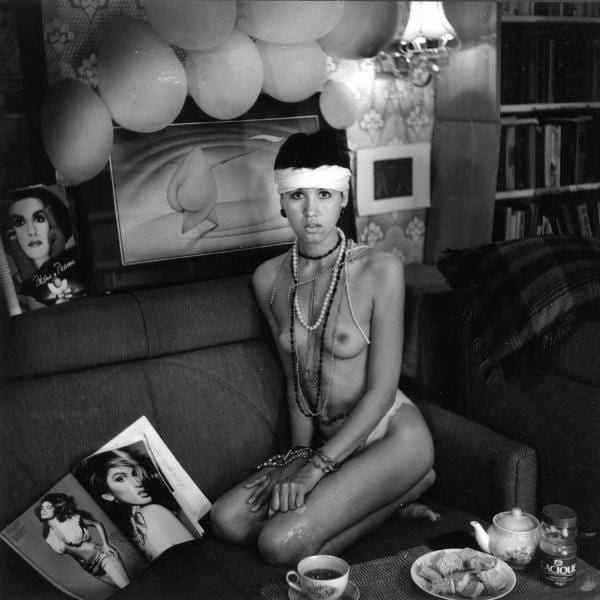

Nikolay Bakharev’s emotive and controversial images are important social documents that enlighten and inform the viewer. The subjects – freed from oppression by this oppurtinity to express grace and fragility, desire and control, honour and sincerity – are merely a means of expression for the photographer: every image gives us an enhanced view of the ‘bigger picture’.

Nikolay Bakharev was born in 1946 in the village of Mikhailovka, Siberia. He now lives and works in Moscow and Novokuznetsk. With help from Moscow’s Regina Gallery, Gomma contacted Nikolay Bakharev in Siberia for this exclusive interview.

LD: How did you find your subjects?

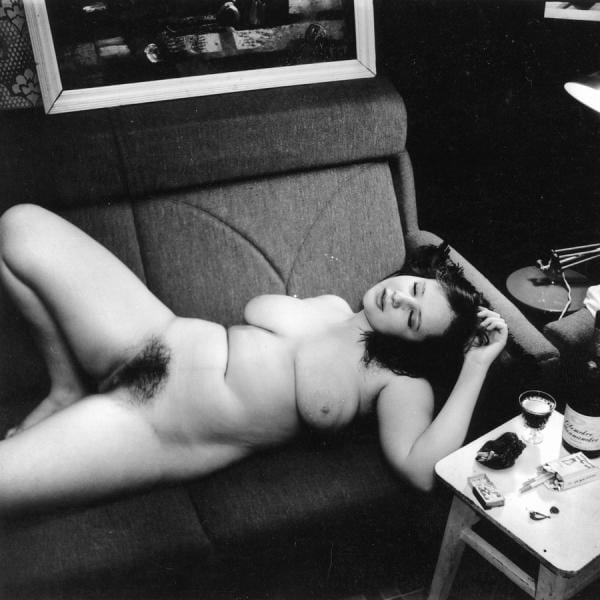

NB: In the 70’s I worked as a photographer at the Communal Services Factory of Novokuznetsk. I went to schools, kindergartens, funerals and weddings, visited hostels and private apartments offering various photographic portraits. Yet, it wasn’t interesting for me to photograph groups at schools and kindergartens, and I had to make 20-30 prints of each frame… It was boring, irritating, but it meant good money. Like many amateur photographers in this country, I wanted to do something creative. I always bought and read Sovetskoye Photo, Czech Photo Revue, German FotoMAGAZIN. During the same period I started going to the local beach, initially to make some money, but then I realized that this kind of work could produce very interesting results. As a matter of fact, the beach was the only place where people were allowed to bare their bodies without provoking a negative reaction from the Soviet society at the time. Our morals forbade us to be nude in front of strangers. There was also a clause in the Criminal Code which banned the distribution of nudity in photographs, so it put off most photographers from approach this theme. That is why people posed cheerfully before a photographer at the beach without any reservations or shame. Thus, a cycle of beach works appeared and later many beach clients also expressed their desire to have photographs taken at home.

LD: Did the political or social situation in Russia influence your creative work?

NB: In the past the political and social situation restrained me in the choice of themes and plots, it limited the access to the viewer, which is very important at a young age; it created a strange perception of the environment when the values promoted by propaganda did not correspond to real life. Many photographers, who worked with social topicality or with nudity, were forced to accumulate their material in “desk drawers”. In my time I tried to get an official permit to shoot nude models in my studio at the Communal Services Factory where I worked then; I went to the municipal and regional party committees for support trying to substantiate my claims with the fact that the openness of such work would help somehow monitor this activity. But they said, “You should be thankful that you haven’t been sent to prison yet.”

LD: You seem to have a dialogue with the person you are shooting. Does this dialogue pursue certain goals, or does it emerge by itself in the work process?

NB: The dialogue with the portrayed person is quite conventional because many things have been read, seen and heard. Looking through the prism of this cultural baggage produces the subjective vision of the portrayed person, so there’s no need to warm myself into his or her confidence to SEE the person. The conversation with the person you shoot is commonplace, just the usual “where”, “who”, “when” etc., but the dialogue in the portrait is a norm for any artwork; something you attain after many hours of work. This dialogue is spontaneous and depends on professional skills and chance. If this is not so, then it is not a portrait, it is a report which flies past without leaving any imprints on the subconscious, leaving no trace of someone’s life.

“I catered to their desires and tried to inject my own aesthetical and psychological interests into the moment of shooting. Typically, the clients rejected these ‘ugly pictures’, but they were informed that they could be displayed at some exhibition.”

LD: You were one of the first photographers to deal with such intimate subject matter. What was the reaction of the people you shot? Was it desire, fear, excitement or the feeling of freedom?

NB: While initially clients bared themselves out of simple interest in their bodies, later I discovered that the person in such a state forgets about the public morals, and a more confidential attitude appears which forces the client to communicate more frankly. Having read a lot of articles in many magazines about the psychological portrait, and looked through art and photo albums of various authors (Zander, Bresson, Koudelka, Binde, Salgado, Mikhailovsky, Newman, Nappelbaum and others), I found out for myself that the human being is interesting with his or her own openness and frankness, and that it has nothing to do with an exalted spirituality and beauty which seems to be hidden in any person and must be revealed. Unable to discover this spirituality and beauty myself, but seeing that my clients wanted their images to fit these ideals, I catered to their desires and tried to inject my own aesthetical and psychological interests into the moment of shooting. Typically, the clients rejected these “ugly pictures”, but they were informed that they could be displayed at some exhibition. There was also a clause in the Criminal Code which banned the distribution of nudity in photographs, so it put off most photographers from approach this theme.The clients would only exclaim in surprise: “Who will take them?” and nobody took them in fact, until 1987, when the All-Union Photographic Show in Moscow dedicated to the 70s anniversary of the revolution, first displayed the social works. Since my clients mainly ranged from workers and students in hostels, to the people at the beach who then invited me for private sessions (mainly working class), they did not have any special requirements except “make it beautiful, man”. If they bared themselves, which is what I tried to make them do, they almost never ordered those photos, or took them for free and hid them somewhere.

I had problems later, when somebody discovered them, and well, then I had to listen to some hard language from the bosses. Just operational costs, as they say. While earlier clients almost never took away their nude photos, nowadays, in the last 5-7 years, many people have begun to take them as I give them for free, although all the rights concerning these photos belong to the author.

“My technology of work and communication with people is still the same, just as it was 30 years ago, but the skills have become more automatic which is a great problem and my approach to the portrait is more conscious and motivated.”

LD: Your photographs produce a certain awareness of “fashion”. Was it your intention to show freedom as something fashionable, something that must form part of the way of life, or is it the influence of recent fashion trends seen in your work?

NB: If you mean the fashion for nudity and frankness associated with it, it is the tendency of the global mass culture about which I do not really care a lot. I see the difference between inner morality and public morality as the behaviour and ethics regulating relations in the mass environment. The fact that people are interested today in the inner morality may be associated with the change in the political situation in this country. Although men of letters had always depicted it, this was absent in the documentary sphere due to the natural dependence on behavioural stereotypes formed in the society at any given moment.

My technology of work and communication with people is still the same, just as it was 30 years ago, but the skills have become more automatic which is a great problem and my approach to the portrait is more conscious and motivated. There is no great demand for a certain topic in photography in our province because there are no advertising agencies and no publishing houses wanting to use certain topics. As for freedom, it stays inside people just as it stayed there before. You just have to win their confidence and leave their inner morality unviolated.

LD: Do your subjects have the copies of their images and what do these mean for them?

NB: All the photographs were ordered by certain clients who agreed to pose for several hours and then selected the pictures they were interested in among the contact prints offered. So I give them all the photographs they order.

“In my work I destroy notions concerning the morals of an ordinary person, exposing the environment of his/her life and I am well aware that the reality I depict would never win recognition from that very ordinary person.”

LD: What does photography mean to you?

NB: Photography is one of the channels through which the present penetrates into the future, just as the art of the past got inside us. For me photography is a means to express systems of opinions and values, the author’s ideology.

LD: What are you currently working on?

NB: When I finished the photographic projects for the Regina Gallery and the Afisha Magazine, I started on a project suggested by the Moscow Photography House. The goal of this project is to create a contemporary photographic chronicle of Russia through a series of provincial portraits. I’m pursuing a broader aim, which is to compose a gallery of human faces that, by reading the subconcious level in the memory, will change the attitude of the ordinary people of Russia.

LD: Do you believe that contemporary photography emphasizes the form rather than the content?

NB: In the 1980’s there was a discussion among creative photographers about the documentary as a sphere of global mystification. It is precisely these photographers, I mean G. Kolosov, I. Mukhin, V. Shchekoldin, V. Syomin, S. Chilikov, S. Osmachkin, M. Ladeishchikov, A. Pashis, V. Vorobyov, A. Trofimov, V. Sokolayev, A. Bokin, V. Shabankov, who helped me to consolidate my stand against the distortion of reality. “Social” was a fashionable term then. Various trends in photography appeared for the first time after a long period when nothing else was allowed in photographic creation except “Stop, this moment, you are beautiful” and the Cartier-Bresson approach to reporting. Many people played the theatre game, of photographic life. In their interpretation reality of that sort looked empty, invented, pure entertainment. Photography of this kind would actually operate with the form ignoring the content. I wanted to arrange my work to counterbalance the creation of these authors.

LD: Do you regard yourself as a social artist?

NB: Society sets up limits for ourselves through the morals which are, to a certain extent, violated by the society itself. In my work I destroy notions concerning the morals of an ordinary person, exposing the environment of his/her life and I am well aware that the reality I depict would never win recognition from that very ordinary person. Certain courage is necessary for it, since the social genre is a drama deprived of any entertainment aspects, fully appealing to the civil, social emotions of the viewer, arousing empathy.

They often accuse me of the fact that the material I have collected represents the society as something spiritually deprived and impoverished and the human being looks miserable and ugly in it. Yet, a certain notion of our life is created to the extent of the recognition of reality by the viewer, making me thus, a social artist.

LD: What is the influence of the present political and social situation in Russia upon your creative work?

NB: The political situation has practically no influence on my creation, if you skip the fact that I am no longer looking around with fear, I am not afraid to be caught by the police or KGB. As for my clients, they are opening up in front of the camera as they did before but they no longer believe that I am doing something forbidden.

LD: Do you think that photography needs to have a sense of rawness, a sense of sincerity?

NB: It is precisely ordinary life registered without any beautification which makes the borders of a stranger’s life transparent, makes us intimate with the other person. As for the creation of types who, instead of living, display what their author “knows”, who are deprived of openness, who are not natural, they will find themselves outside human relations and will hardly move the viewer. In the absence of inner spiritual force and integrity we can persuade other people only with our SINCERITY. My work has taught me that you can impress concrete people only through cultural drive, using the language they understand. That is why I have to mask my actions with interest in the wishes of my clients during the work process exploiting the stereotypes of beauty floating in the minds of people which suddenly turn into frankness when tested with reality. This frankness which is often shocking has many times produced accusations that I create the world peering through the keyhole…that I promote triviality. From my point of view, I expose the nature which people do not want to admit to, if it does not fit their notions of themselves.

Orignally Published in Gomma Magazine – Issue 2

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher