Disfarmer Rediscovered

By Michael P. Mattis, from the book Disfarmer, The Vintage Prints

The legend of Mike Disfarmer has intrigued the photographic community for nearly thirty years. The bizarre story of a hermit-like Arkansas studio photographer named Mike Meyer legally changing his name to Disfarmer in order to disassociate him- self not only from his family, but from the very farming community of Heber Springs in which he plied his trade, is irresistible. But even more compelling are the pictures themselves. The beautifully sequenced book by Julia Scully and Peter Miller that introduced his work to the art world revealed searing portraits from the American heartland, captured at a defining moment in history in which the Great Depression yielded to World War II, and the sons of the farm donned their country’s uniform and headed off to foreign shores. The camera’s unsentimental gaze suggests a photographer who was simultaneously an insider and an outsider in his own community.

Scully and Miller’s book caused a sensation at the time. “Nobody famous ever posed for Mike Disfarmer,” Gene Thornton wrote in ARTnews, “but his portraits are among the best ever taken by any photographer.” Richard Avedon termed the book “indispensable”; his own series of rural portraits, In the American West, published a decade later, reveals a kinship with and likely the influence of Disfarmer’s unblinking eye. To Sean Callahan writing in the Village Voice, Disfarmer’s portraits constituted “a compelling and compre- hensive record of the home front from 1939 to 1946 … a microcosm of the nation during hard times.” And in its end-of-year review, the New York Times hailed the book and the accompanying exhibition of posthumous enlargements at the International Center for Photography as one of the ten outstanding photographic events of 1976 – stating flatly that Disfarmer’s portraits “can stand comparison with August Sander, Diane Arbus and Irving Penn.”

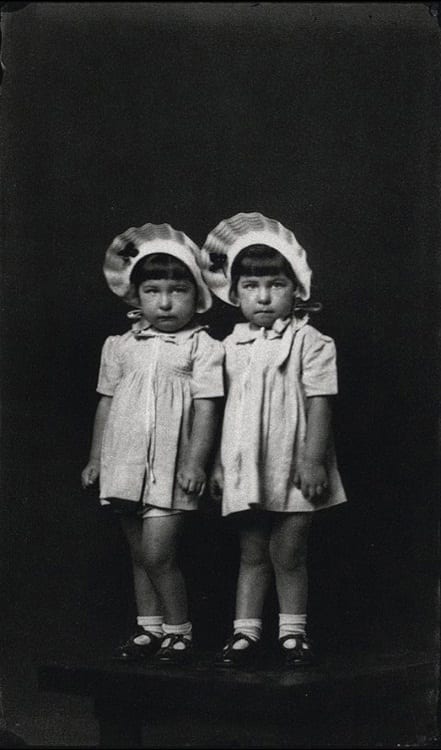

Figure 1

So it was somewhat deflating for collectors to learn that no original vintage Disfarmers could be had. Rather, the discovery of this photographer stemmed entirely from a trove of 4000 glass-plate negatives that had been rescued from destruction by Joe Allbright, a retired army engineer who had purchased the contents of Disfarmer’s studio after his death; the negatives were later given to the local newspaper publisher Peter Miller. Scully’s essay contained the tantalizing comment, “Many of these originals are still to be found in the photo albums of Heber Springs families,” but rumor had it that some enterprising art dealers had already flown down to Arkansas in search of such “originals,” only to have doors slammed in their faces by the untrusting locals.

The present historical reclamation project began in February 2004, when I was serendipitously offered the family collection of vintage Disfarmers assembled by Ashleigha and David Pratt, a young couple who had grown up in Heber Springs and recently relocated to Chicago. The intimacy and sheer beauty of the vintage contact prints was undeniable and a spur to action. With Scully’s tantalizing comment as a touchstone, a dedicated team of historically-minded locals was quickly trained and mobilized; ultimately they combed every dirt road in Cleburne County in search of Disfarmer originals. From the outset, an integral part of the project was educating an initially skeptical rural community that their albums of old family photos were likely to contain objects of significant artistic and cultural value that could – and indeed should – be brought to the attention of a wider audience. To this end, art researcher Hava Gurevich joined the project to gather oral history and perform geneological research. In addition, members of the team worked closely with the Cleburne County Historical Society, providing materials for exhibitions that celebrated Disfarmer’s achievement. Today, after nearly two years, it can categorically be stated that the bulk of Disfarmer’s extant oeuvre has been recovered.

What have we learned along the way? To begin with, note that prior to the present book, all published Disfarmer portraits dated from the short period 1939-46 corresponding to the dates of Allbright’s cache of glass negatives. So it is especially eye-opening to have uncovered vintage prints spanning Disfarmer’s full 40-year career in Heber Springs.

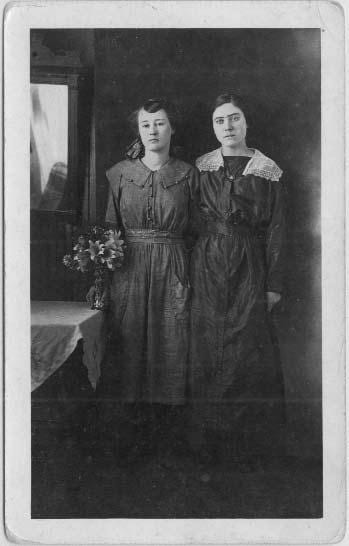

Figure 2

Dated examples in the collection range from 1917 to 1956. Thus anxious young soldiers are portrayed prior to shipping off, not only to World War II, but also to World War I [Plate 1142], whereas towards the end of his career (when his anachronistic glass plates do inevitably give way to film negatives) Disfarmer’s previously somber camera joyfully captures the pairings of bobby-soxed young women with their James Dean wannabe boyfriends.

Much that is new can now be said about Disfarmer’s life work. Mike Meyer/Disfarmer is known to have settled in Heber Springs some time after 1910 ; by 1915 the Penrose & Meyer Studio was open for business in the lobby of the Jackson Theatre, an elegant Victorian building on the south side of Main Street. During this time Heber Springs was undergoing a revival as a spa town. Figure 1 illustrates a photograph that bears the rare Penrose & Meyer Studio stamp on the verso and is dated 1917. Whereas hints of the later Disfarmer “look” are certainly present, the psychological power of the double portrait is attenuated by the typical props of a turn-of-the-century studio, in this case a mirror, a tablecloth, and a floral bouquet.

Figure 2 shows the freestanding moveable backdrop that appears in most of Disfarmer’s portraits between 1918 and 1928 [Plates 1780-1224]. The painted trompe-l’oeuil features include a pulled-back curtain to the left, a Roman “temple,” and an overall pattern of clouds and/or foliage. Often the subjects from this time period pose on an oriental carpet.

Figure 3

Figure 3 depicts the freestanding moveable solid black backdrop that characterizes the majority of Disfarmer’s work beginning around 1930. The spare and somber background seems appropriate for a time in which prosperity in Heber Springs had come to a halt and the Great Depression had settled in for the decade. Starting in 1940, this black backdrop alternates in usage (possibly depending on the available natural light) with the distinctive Mondrian-like white background with black stripes shown in Fig. 4. It is these two backgrounds that are already familiar from the earlier publications, and that, to modern eyes, harmonize most successfully with Disfarmer’s psychologically direct approach to portraiture. The two backgrounds continue past 1950, although in that decade Disfarmer’s overall productivity seems to have dropped precipitously.

Figure 4

Disfarmer’s output was not wholly confined to the studio. Longtime residents of Heber Springs recall a gangly, Zorro-like figure in a black cloak riding about town on his horse, view camera and tripod at the ready, offering to photograph families relaxing on their porches; a particularly fine early exam- ple bears the Penrose & Meyer stamp. And on weekends he frequently set up his camera in Spring Park, a central gathering place for the young and young-at-heart.

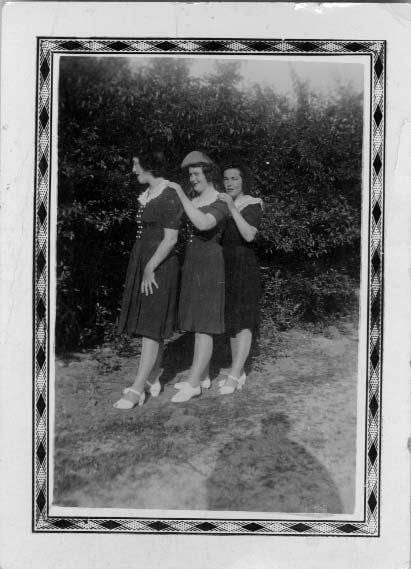

Figure 5

Figure 5 shows one such photograph; the light-hearted spirit is disturbed by the ominous shadow of the photographer hunched under the black cloth. The diamond border of this small-format print dates it to 1935-1938 which is when Disfarmer favored this particular stock.

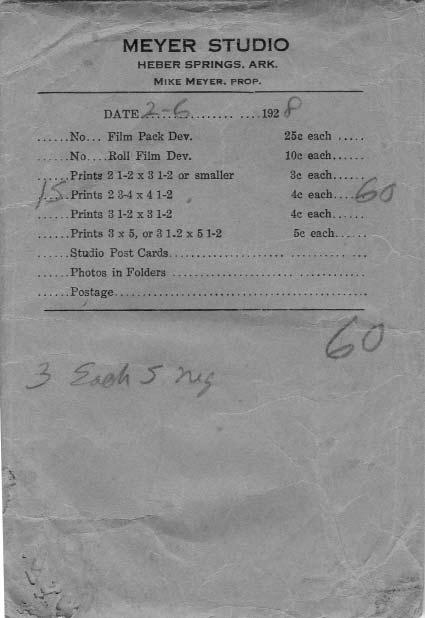

Despite the dramatic changes in his studio interiors, physical addresses, and of his very name over the span of his career, Disfarmer did manage to hold the line on prices. Figure 6 reproduces his price-list from 1928. A single-picture sitting cost 50 cents and included three free prints; additional prints ranged from three to five cents each depending on size. An Edward Weston nautilus shell, which at that time would have cost $25, seems pricey by comparison.

Figure 6

How to summarize Disfarmer’s (dare I say) artistic achievement? By virtue of his trade as a small-town studio photographer, Disfarmer was the ultimate insider, privy to each family’s rites of passage – from first birthdays to high school graduations, engagements and army furloughs, anniversaries and reunions – as well as to the private joys of close friends celebrating a night on the town. But in fundamental ways (described in detail in Woodward’s essay in the present volume) he remained a lifelong outsider: an agnostic from Lutheran stock among church-going Baptists and Methodists, the son of a German-born Union soldier in the heart of the South, a man of perception among men of action, a confirmed bachelor in a community of large families. In my view, it is this unique insider/outsider mix, so evident in the pictures themselves, that is the essence of his genius, and the reason why – despite three decades of intense searching – no other studio photographer from that era has been uncovered whose accomplishment remotely matches Disfarmer’s.

1 J. Scully and P. Miller, Disfarmer: The Heber Springs Portraits 1939-1946, Addison House, Danbury, N.H.,

1976.

2 ARTnews, November 1976.

3 Village Voice, January 1977.

4 New York Times, 26 December 1976.

5 At the time, the only other major photographer for whom no original vintage prints were available was the chronicler of the French belle époque, Jacques-Henri Lartigue, who was born ten years after Disfarmer; but unlike Disfarmer, since Lartigue lived into his nineties, modern signed prints could be ordered. In the last decade vintage Lartigues have finally surfaced, as several unique family albums have been disassem- bled; as with Disfarmer, these are contact prints (see Imprints of Joy, Edwynn Houk Gallery catalog, 2000).

6 Most vintage Disfarmers are printed on Azo or Velox papers which were high-quality papers that were particularly well suited to contact printing (with the exception of the dustjacket, the prints in the present volume are reproduced actual size). Over his long career Disfarmer experimented with many different types of such papers, both single- and double-weight, warmer and cooler toned, and in finishes ranging from dead matte to high gloss.

7 The prior literature consists of J. Scully and P. Miller, op. cit., and the revised and expanded edition, Twin Palms, Santa Fe, 1996; Toba Tucker and Alan Trachtenberg, Heber Springs Portraits: Continuity and Change in the World Disfarmer Photographed, UNM Press, Albuquerque, 1996; Aperture magazine no.

78, 1977; Photography Year 1977 Edition, Time-Life Books, New York, 1977.

8 Fewer than 20% of the photographs are dated, some by hand by the sitters, others with Disfarmer’s 6- digit ink stamp in which the first four digits give month and year, and the last two digits indicate the neg- ative number.

9 For further details, see R. Woodward’s essay in the present volume.

10 His estranged family members reported to Scully that Disfarmer and his mother moved from Indiana, but Disfarmer told at least one close acquaintance that he had actually lived in Elmira, NY, prior to Heber Springs (Col. Carl F. Baswell, interview with Daniel Hipp, 18 June 2005). The 1920 Cleburne County cen- sus lists his occupation as photographer and his birthplace as Indiana.

11 Unfortunately, very little is known about George A. Penrose.

12 Other, less common, backdrops are also occasionally used prior to 1930.

13 Evalina Berry, Time and the River: A History of Cleburne County, Rose Publishing Co. Little Rock, Arkansas, 1982, p. 270. The cautionary note should be sounded that the large majority of the outdoor shots from Heber Springs, even those bearing one of Disfarmer’s studio stamps, were not made by Disfarmer but merely printed by him, as his studio performed such standard photo-finishing services for the com- munity.

14 See also Plates 1959-2166, 1738-1726, 1378, and 1684-2193.

Disfarmer: the Vintage Prints.

Photographs by Mike Disfarmer. Texts by Edwynn Houk, Gerd Sander, Richard B. Woodward, Michael P. Mattis

Powerhouse Books, 2005. Cat# PY172 ISBN-10: 1576873048

ASX CHANNEL: MIKE DISFARMER