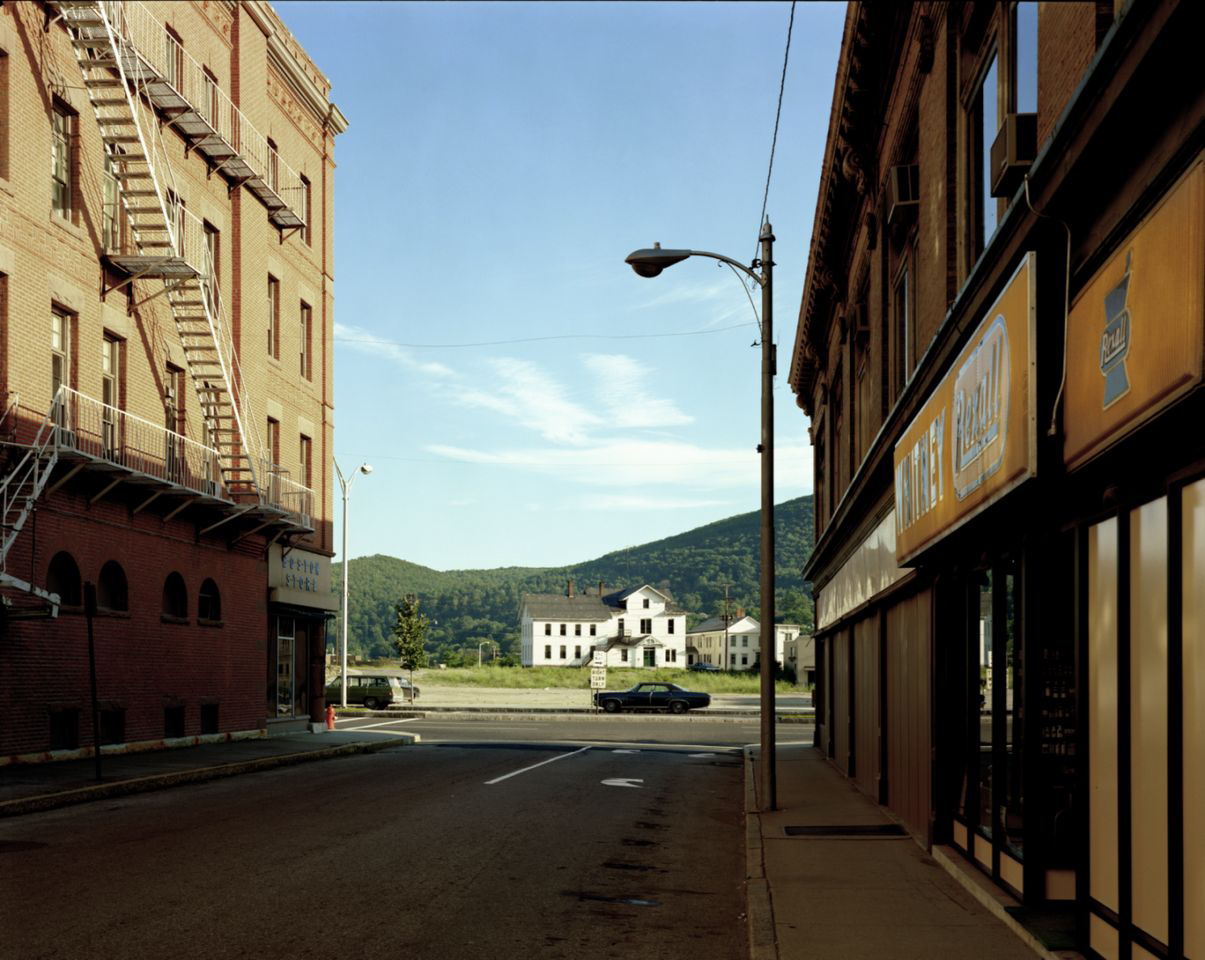

From the series American Surfaces

Looking at Stephen Shore’s large-format pictures of America, it might be hard to believe the images were once controversial.

The Landscape of Stephen Shore at the ICP

By Carl Gunhouse, May 22, 2007

Looking at Stephen Shore’s large-format pictures of America, it might be hard to believe the images were once controversial. In retrospect, the pictures look to be squarely located in a rather clear history, starting with Carlton Watkins and proceeding through to current German photography. But during the early and mid seventies large-format color photography was anything but common.

Shore began his most renowned body of work, Uncommon Places, in 1973, two years before the New Topographic show at Eastman House that cemented the large format camera as a tool for making contemporary art, or three years before the publication of William Eggleston‟s Guide, which forever placed color photography in the ranks of “art-photography,” and fourteen years before Joel Sternfeld‟s more accessible book, American Prospects. By 1973, 35mm black & white photography was no longer struggling to be seen as art among photographers: it was art.

Those who had fought for acceptance in the sixties had succeeded. Garry Winogrand was no longer defending his images against accusations that they were nothing more than chaotic snapshots: he was teaching full-time at the University of Texas. Diane Arbus had died, but left behind a highly regarded retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art. And Lee Friedlander‟s defining book, Self Portrait, had just been published. The photographic art establishment was 35mm black & white photography. And as a result, good young photographers everywhere questioned the accepted hierarchy and did something else.

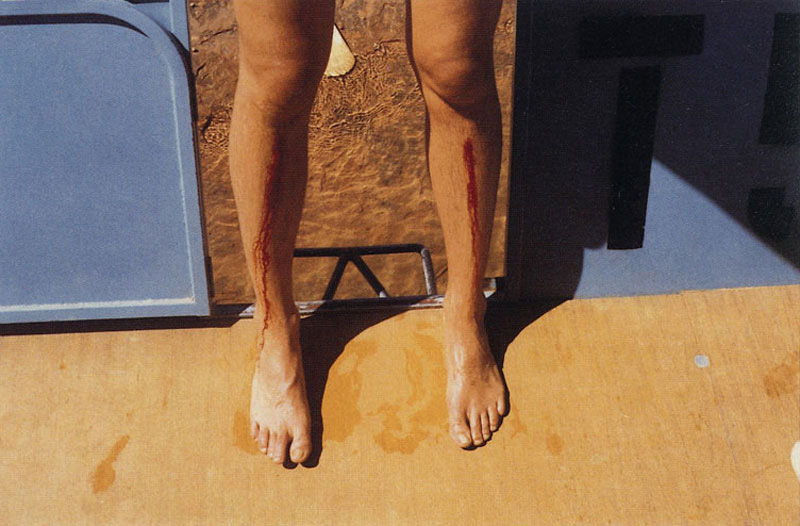

From the series American Surfaces

It was work that clearly fit the greater art trends of the early seventies, yet it seems to have proven unsatisfying for Shore.

This chafing under what was defined as art photography is delightfully illustrated in ICP’s Biographical Landscape: The Photography of Stephen Shore, 1969-79. Shore, as many now know, came early to photography, selling his first pictures, 35mm black & white street photographs, to the Museum of Modern Art at fourteen. By twenty-four, he had a solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Biographical Landscape‟ starts with the more mannered conceptual photographs he made after a stint documenting Andy Warhol‟s Factory. His work from this period echoed Ed Rushca and to some extent Warhol. He photographed in a serial manner like Avenue of Americas, where he walked up the avenue making a picture at the end of each block. He created work that hinged on a self-imposed set of limitations, which removed a portion of the artistic intent from the maker and left it up to faith that at the end of each block there would be something to photograph.

The images could only be understood if seen in the series that would hopefully reveal the limitations the artist had chosen for himself. It was work that clearly fit the greater art trends of the early seventies, yet it seems to have proven unsatisfying for Shore. At the ICP, conceptual series pictures are exhibited in the same room as images from “All the Meat You Can Eat”, a show of pictures declared obscene and seized by the district attorney of Amarillo, Texas. The show included images of masturbation, military flyovers and dead bodies, as well as a picture of a mass grave donated by Warhol. When not enthralled by the vernacular images from a local DA, Shore was creating vernacular postcards of Amarillo Texas. Gradually the world and how it was seen in photographs was overwhelming his earlier, more academic interests.

From the series American Surfaces

In 1972, Shore drove from New York City to Amarillo, Texas making photographs that documented everything he did in a style that mirrored your average snapshot.

Within a year of his solo show at the Met, Shore was on the road photographing American Surfaces, a body of pictures that is now largely seen as the key to deciphering his more popular Uncommon Places work. In 1972, Shore drove from New York City to Amarillo, Texas making photographs that documented everything he did in a style that mirrored your average snapshot. It was an attempt to make art in the world that would reflect his own existence, yet maintain a discernable conceptual content.

He was taking pictures Warhol might have made if he was riding shotgun with Robert Frank. The images covered a wide swath of all parts of America and its broad culture: while remaining art objects that intentionally looked like a snapshots even if they contained things no discerning tourist would bother to remember: toilets, TV dinners, unremarkable intersections, and random strangers. The work served its purposes well: it created a very detailed diary with no central character. The pictures become the diary of an invisible man: you know his whereabouts from the spaces he inhabits, the food he eats and the people who notice his existence, but he is never seen or heard. The presentation of his 3×5 glossy dime-store prints later that year at LIGHT Gallery were at best thought of as highly crafted snapshots.

After John Szarkowski questioned the formal quality of the American Surfaces work, Shore decided to return to the road but with a larger format camera, at first a 4×5 and then a 8×10. The resulting pictures, made over the next seven years, would become Uncommon Places. These pictures also comprise the majority of Biographical Landscape. They are without question his most successful body of work. The pictures pick up where American Surfaces leaves off: once again Shore is photographs the things he eats, the places he sleeps, the people he meets and, most memorably, the little slices of American landscape he sees while wandering unspecified streets.

The facts of his travel make up the heart of the work: pancakes, beds, hotel rooms, generic paintings on desolate walls, abandoned streets, and the occasional welcoming face. The pictures are the shared experience of anyone who has traveled on their own in the world. It is the visual account of a dog-eared copy of a 70’s Lonely Planet America. The world seen by travelers everywhere is painstakingly recreated in visual terms, allowing the viewer to see the world as one might assume Shore did. The pictures become transparent. Viewers are no longer reading another‟s diary, as in American Surfaces, but forced into writing a diary, of a trip they never took.

What makes the pictures sing is Shore‟s breathtaking ability to create a world that seems so every day, but contains elements of transcendent beauty that obliterating anything undertaken by nature photographers like Ansel Adams or Elliot Porter. Shore creates a seamless image that makes the viewers feel they are the ones who noticed the light streaming through a telephone booth, the dance of telephone wires over a dusty street, the color of a turquoise pipe, the sky

reflected in the hoods of parked cars, and generally how great our world can look if one takes some time.

The lack of a personal visual style might have been the result of the working through of visual problems, but in the end it allows those who like looking to feel that if given the chance they might be able to see the world as wondrously as Shore did. At the close of the Uncommon Places work, Shore returned to more conceptual territories, making images that de-constructed scale, perspective, and sequencing: he returned to making pictures about how the camera sees. At times these are interesting, but they are not nearly as fulfilling as the world we were lucky enough to see through his rather generous eye.

Around the WEB: Stephen Shore

* 303 Gallery: Stephen Shore

* Wallpaper Magazine: Stephen Shore Interview

* “American Surfaces” at PS1

* MoCP: Stephen Shore

* NY Times: “Passing Mile Markers, Snapping Pictures”

* Doppelganger Magazine: Stephen Shore Interview

* Bill Charles Represents: Stephen Shore

ASX CHANNEL: STEPHEN SHORE

(© Carl Gunhouse, 2007. All rights reserved. All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher)