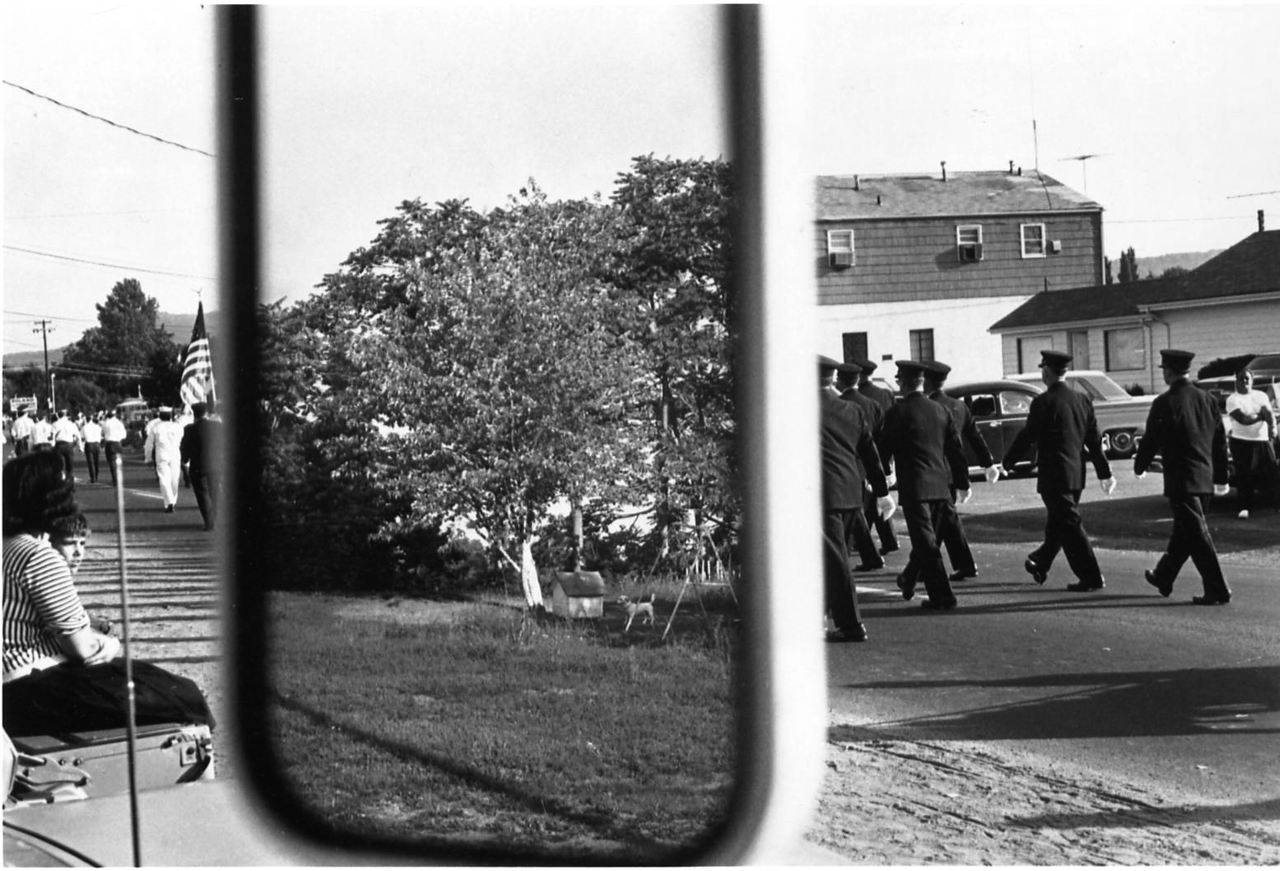

Haverstraw, New York, 1966

Friedlander is a photographer, never forget. Although a major photographic artist, he is not an ‘artist utilising photography.’ He uses the camera, that unthinking machine, to transcribe his visual perceptions of the world.

By Gerry Badger, from Creative Camera (1991)

‘That scrawny cry – it was

A chorister whose c preceded the choir

It was part of the colossal sun,

Surrounded by its choral rings,

Still far away. It was like

A new knowledge of reality.’

Wallace Stevens

The second essay I ever wrote upon the subject of photography was about the work of Lee Friedlander, on the occasion of an exhibition of his pictures at the Photographers’ Gallery, London, in 1976.2 Now, some fifteen years later, a much larger retrospective, Like a One-Eyed Cat, arrives at the Victoria and Albert Museum, having the benefit of much fine work completed in the interim, and accompanied by the most extensive monograph on the photographer to date.3 And published almost concurrently is the eagerly awaited volume of his remarkable and controversial studies of the female nude.4

We might hope that, as a result of all this activity, one of the pre-eminent figures in post-fifties photography will at last be given the recognition in this country his widely influential imagery merits. It is important too, that the Friedlander picture is brought up to date for us. The 1976 Photographers’ Gallery exhibition, though covering a career of a dozen years or so, dealt essentially with what might be termed the ‘classic’ Friedlander style, principally those familiar, raddled urban landscapes, full of fractured reflections, disruptive telegraph poles and other spatial manipulations – the style which was so instrumental in defining the ‘social landscape’ school and the visual vocabularies of three generations of young photographers. Since that date, however, Friedlander’s oeuvre has expanded in scope and broadened considerably in style, separating into distinct and differing strands. Even in his major project of 1976, The American Monument5 – elements of which were seen at the Photographers’ Gallery – the classic style was in the process of refinement and simplification. A few commentators were puzzled by the plainness of many of the images in that study, the photographer’s contribution to the bi-centennial celebrations. And these feelings of perplexity were hardly assuaged by the publication in 1980 of Friedlander’s next book, Trees and Flowers,6 which contained deadpan, puritanically straight images of frequently scrofulous pieces of natural vegetation. Certainly it was difficult to tell whether the tree pictures hit a determinedly plainsong or cautiously lyrical note, some critics reading new heights of photographic sophistication and subtlety in their drabness, others simply noting drabness.

Explore All Lee Friedlander on ASX

Following Trees and Flowers, we were kept guessing as Friedlander continued to visit other photographic territories in bewildering succession, keeping, it would seem, several balls in the air at any one time by working on different series concurrently. To his burgeoning repertoire he added, or rather revealed, intimate portraits of family and friends,7 and he has made several extended essays documenting the modern workplace,8 culminating in a startling series detailing the numbed faces of office workers concentrating furiously upon their computer monitor screens. And now, the supposedly cool Friedlander has turned to a decidedly hot subject, presenting his disturbingly fleshy (and hirsute) nudes, a subject we suddenly find he has been exploring surreptitiously for the past decade-and-a-half.

Needless to say, such profligate versatility has caused a deal of headshaking amongst those many commentators who find it ideologically necessary to demonstrate both stylistic and subject unity in the work of any ‘serious’ artist. Friedlander, it is contended, already under suspicion because of his penchant for visual humour, cannot be totally serious. Why does he insist upon confounding us with this disparity of subject matter and confusion of style? This ‘problem’ was already apparent in 1976. Friedlander’s jocularity and overt displays of formal virtuosity tended to mask other aspects of his work, thereby raising questions about its ultimate meaning. In my earlier essay, for example, I asked the following:

‘Just what is Friedlander’s work about? To what does it refer, either concretely, metaphorically, formally, allegorically, or representatively? In what sense are his photographs documents – either of the world or of his true perceptions? Is he confronting us directly with our perception of reality – or merely an abstract, ultimately barren non-reality? Is his work an allegory for his view of civilisation and humanity – or is it only about the medium in its narrowest sense? Is it a series of facile formal manoeuvres? Or even a kind of existential jerking off?’9

Martha Rosler, in one of the finest essays ever written about Friedlander – or modernist photography for that matter – was overtly dubious, conceding the efficacy of the pictures’ form, but disputing whether they had much meaning, other than those deriving from how those forms were disposed within the frame, or meanings so reeking of ambiguity as to be irritatingly fey and inconclusive:

‘The locus of desired readings is, then, formalist modernism, where the art endeavour explores the specific boundaries and capabilities of the medium, and the iconography, while privately meaningful, is wholly subordinate. . . The level of import of Friedlander’s work is open to question and can be read anywhere from photo funnies to metaphysical dismay.’10

Mount Rushmore, South Dakota, 1969

To be sure, Friedlander is patently an artist as well as a photographer, entranced by the medium as well as involved in the message. He is quite willing, and certainly able to range consciously over a wide spectrum of meaning and artistic expression, ranging from the formal to the contentual, from the concrete to the metaphysical – often, it would seem, in a single image.

Like a One Eyed Cat reassures me at any rate of Friedlander’s seriousness and depth of purpose. The broadening out that has become apparent in recent years, in terms of both subject matter and iconography, takes us some distance from modernist formalism, I would contend, and much nearer to the realms of the metaphysical. Of course, Rosler might seriously question the socio-political relevance, and therefore the artistic import of metaphysics, while I would take issue with her over the significance of Friedlander’s ‘privately meaningful’ iconography, which is neither so private nor as subordinate as Rosler suggests. Nevertheless, the whole question of Friedlander’s supposed formalism remains tantalisingly open. His formal language, once so strikingly flaunted, has now become so subtle that often, it would seem, it hardly bothers, or needs to declare itself. The photographer, indeed, has refined his formal means to the point where his images seem totally transparent – in a word, they seem almost unmediated records. But records of what? They are not, to be sure, sociological documents in the accepted sense. Friedlander’s work is very different in both form and effect from contemporary exponents of the social documentary or reportage genre, such as Eugene Richards or Sebastao Salgado. Nevertheless, John Szarkowski’s characterising of Friedlander’s imagery as ‘false documents’, which stressed the photographer’s ‘uncompromisingly aesthetic commitment’,11 also falls somewhat short of the mark. At the time Szarkowski used such terms – on the occasion of an earlier Friedlander exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 197412 – they were more pertinent. But as Friedlander’s vision has evolved, and as his contingent aims and interests have become clearer, to pigeonhole him categorically as a simple formalist seems unduly narrow, even trite.

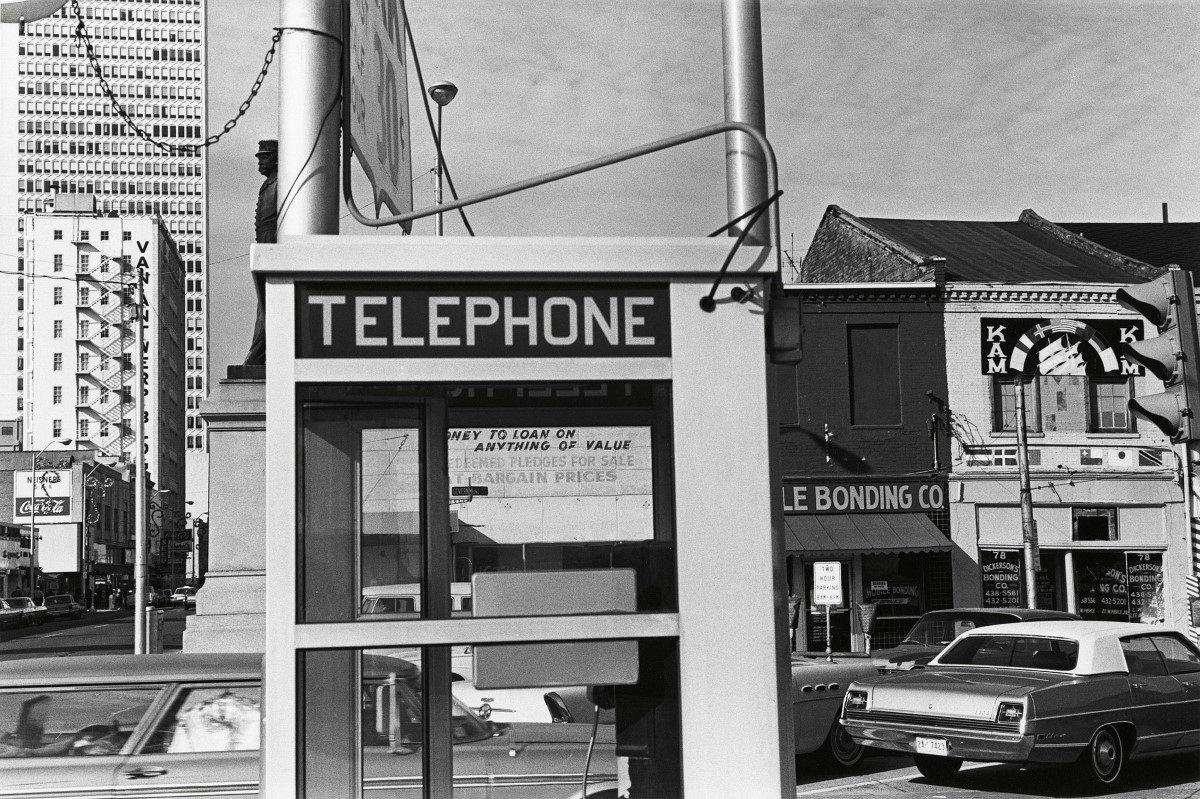

Mobile, Alabama, 1969

He likes to hunt – he is a deadly marksman with his Leica. He window shops, hangs around suburban malls, and above all, being only a half-generation younger than Jack Kerouac, he likes to drive his big shiny American car across the big shiny American continent.

Friedlander is a photographer, never forget. Although a major photographic artist, he is not an ‘artist utilising photography.’ He uses the camera, that unthinking machine, to transcribe his visual perceptions of the world. He would seem to be concerned primarily with pinning down meaningful slices of that thing we call reality and, unlike many knowing postmodern manipulators of the medium – camera conceptualists with attitude – he has faith in the efficacy and worth of his perceptual fragments. He himself gave the most succinct, and perhaps the most candid view of his own nominally modest ambitions near the beginning of his career. ‘I’m interested in people and people things,’ he stated,13 and at this juncture we might see how remarkably true he has remained to that simple dictum and the profound, all encompassing gravitas it implies. Of course, Friedlander has an acute interest in the formal structure of his images, in the games cameras play, but what he photographs matters to him. For example, it matters that he photographs naked women and not naked men. As Ingrid Suschy writes in the afterword to Nudes, ‘he’s not curious about men.’14 And in Factory Valleys, his document of the Ohio and Pennsylvania steel industries,15 the psychological and social consequence of the enforced union between worker and machine surely matters more than, or at least as much as the neat surrealist camera collaging utilised to convey this grievous fact. These ‘workers working, men and women, are heroic in an order of action that transcends consciousness of its own merit,’ Leslie George Katz writes. They are ‘beyond pathos or irony.’16

To be sure, Friedlander is patently an artist as well as a photographer, entranced by the medium as well as involved in the message. He is quite willing, and certainly able to range consciously over a wide spectrum of meaning and artistic expression, ranging from the formal to the contentual, from the concrete to the metaphysical – often, it would seem, in a single image. Lee Friedlander might be a simple photographer, but he does not make simple photographs. In taking an overview of his oeuvre, issues of complexity and conceptual ambiguity surface again and again. Far from being the avant-garde formalist he was adjudged to have been in the nineteen-seventies, a man forging a new tradition of cold, disinterested, rather empty self-referential photography – in which the ‘social landscape’ was in effect an asocial ‘landscape’, or playground of photographic artifice – Friedlander has turned out to be a rather more old-fashioned photographic animal. Upon the evidence of Like a One Eyed Cat, I would contend that Friedlander, like many of the best twentieth century photographers, from Alfred Stieglitz to Nan Goldin, is essentially a diarist. His whole oeuvre, in short, is a record of experience. He has photographed anything and everything that has interested him visually – that has ‘caught’ his voracious eye – from his environment, architecture, and monuments, to trees and flowers, to animals, children, friends, and naked women. In so doing, he has demonstrated, and vindicated the basic impulse of photography – to record one’s visual sense of the world directly as it impinges upon one. This crucial motivating force, this need to reach out and grab hold of reality, is the elemental demon that drives photographers ranging all the way from the weekend snapshooter to the likes of Eugène Atget, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, and William Eggleston.

Just who is this freaked-out, unshaven, unsmiling figure in boxer shorts who stares us down half-dementedly from a hotel armchair? He is a man with as many masks as a Russian doll, masks which he has peeled off gradually over more than twenty-five years, and will no doubt continue to reveal until the last release of the shutter.

According to much current photographic theory, driven by the imperatives of a teaching and academic art establishment that seeks concrete meaning and positive purpose in a photographer, the somewhat meandering, casually contingent, intimate impulse of the diarist would seem anathema. This is the age of the ‘project’, the conceptually driven rather than perceptually driven body of work. Anything which cannot be predetermined, defined publicly prior to shooting, then explicated publicly in a treatise after shooting, is deemed to be substantively wanting and socially suspect, damned by a retrograde tendency to individualism and the private, atavistic doodlings of modernism. The new breed of photographers, heeding the dictates of this orthodoxy, propose and execute their concept orientated ‘projects’ with a will, the worst of them forgetting that art has visceral as well as cerebral qualities, the best of them soon casting aside the theoretical crutch and continuing to do what photographers have always done – marking their perceptual connections with the world. Friedlander too, has followed the ‘project’ path of late, though without quite the systematic fervour and apparent conceptual rigour of the younger brigade. He does not need such rigidly defined perameters. His ‘diary’ differs from most other photographers of a perceptual persuasion in one fundamental respect – it exudes depth, breadth, intention, history, and continuity. Too many photographers have only a few brief years of diary in them. Few have the several decades of Friedlander. The photographic medium, it would seem, has a higher ‘burn-out’ rate than teenage tennis players. Even Garry Winogrand, Friedlander’s alter ego, would seem to have run out of ideas and impulse. Robert Frank and Diane Arbus, in tragically differing ways, might be said to have quit while they were ahead. Only William Eggleston and Robert Adams appear to share the stamina and inexhaustible curiosity of Friedlander.

But let us return to the basic question. What is the substance of this curiosity? This issue cannot be ducked by demurring that the diarist’s musings are necessarily personal and private. Artistic ‘diaries’ – be they literary or photographic – are created for public consumption. Is not much of contemporary art, rooted in nineteen-fifties New York, essentially diaristic in nature? Neither can one avoid the question of meaning in Friedlander by resting one’s case on formalism, by simply stating that his primary interest is formal. Why carp, the formalists would say, when Friedlander is one of the most formally inventive of contemporary photographers, and almost single handedly, has changed the basic way we look at the world in photographs and construct photographic images? Why not leave it at that?

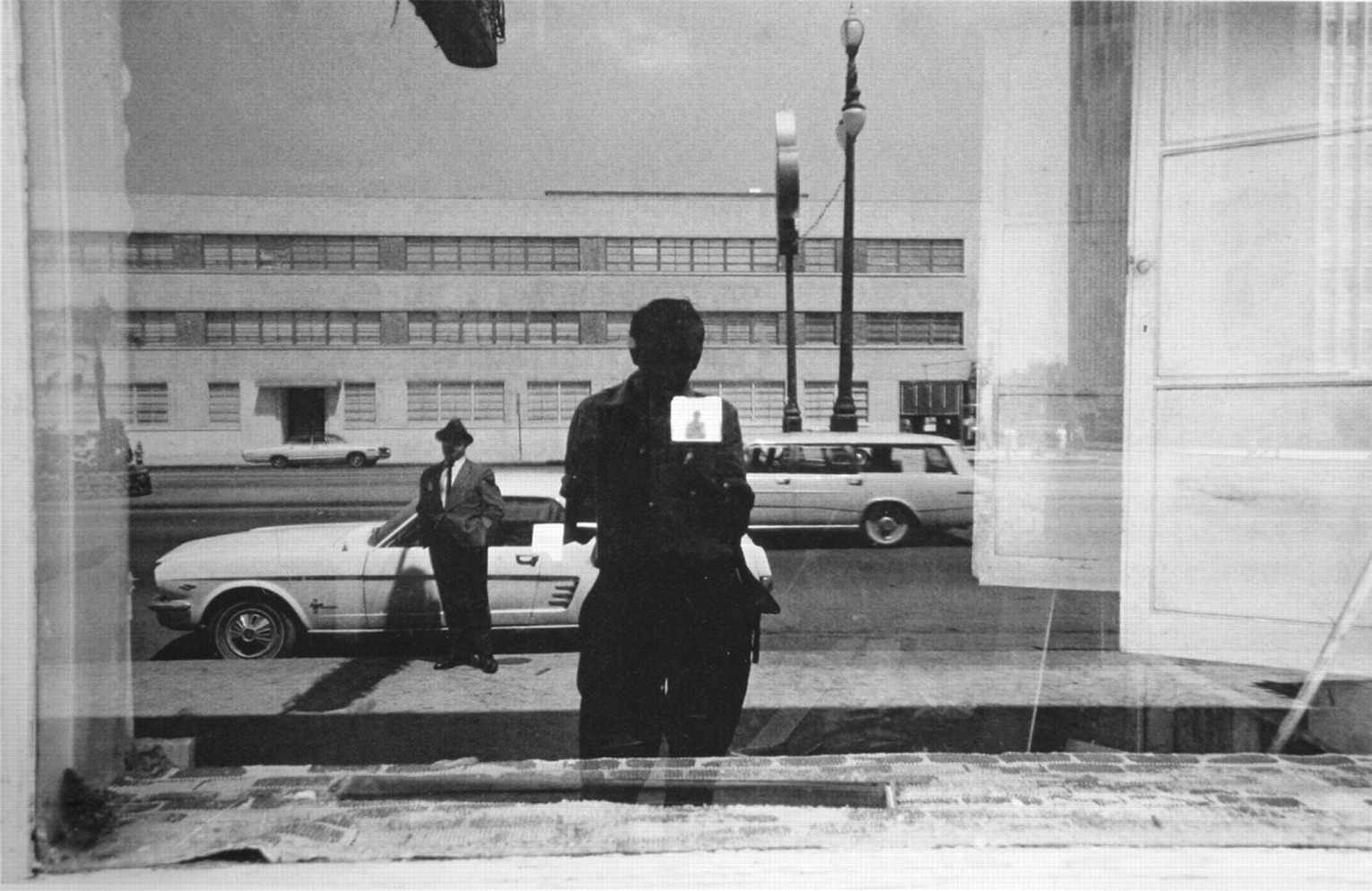

Washington, D.C., 1962

I would contend that Friedlander is as much of a pessimist, supremely adept at suggesting the creepy side of Middle America, as either Arbus or Winogrand – despite their concentration upon the wilder fringes of society or their adoption of more overtly expressive styles.

Unfortunately, the complexity of the issues currently occluding the problems of photographic meaning do not allow us to leave it at that. And Friedlander’s own complexity and net worth warrants more. We can perhaps gain some insight into its substance by temporarily renaming Like a One-Eyed Cat. Let us retitle it Diary of a Nobody, and examine Friedlander as a mid-century, transatlantic Pooter – in Yankee parlance, Joe Average. Certainly, a profile of Friedlander compiled from his diaries indicates that he would fit the bill admirably. He is white, male, of Middle European origin, living somewhere in middle America and holding down either a good blue collar or middle ranking white collar job. He lives in a clapboard suburban house with a porch and backyard, has an ordinary looking wife, two ordinary looking kids, and is himself an ordinary looking, average kind of a guy, with ordinary, average, all-American interests. Looking around his ordinary, average world, Joe notices fairly unexotic things. He notices the suburban environment he inhabits, its buildings and the slightly scruffy spaces between the buildings. He notices his family, his friends and his workplace. He appreciates, amongst other things, flowers, trees, statues, cats, dogs, and ducks. He likes not-too-skinny, not-too-fleshy women, after whom he lusts (thinking his wife doesn’t know) with forthright American gusto, and all the darker undercurrents that might entail. He likes to hunt – he is a deadly marksman with his Leica. He window shops, hangs around suburban malls, and above all, being only a half-generation younger than Jack Kerouac, he likes to drive his big shiny American car across the big shiny American continent. So far, ordinariness is the keynote. Joe is just an ordinary, average benefactor of the post-war American Dream. Thus there is little on the surface of Friedlander to suggest many affinities with the wholly disaffected, alienated visions of his fellow New Documentarians,17 a disaffection that could be said to have begun in the fifties with Robert Frank. There seems little of either the psychological angst of Arbus or the misanthropy of Winogrand. Friedlander seems altogether more affirmative and laid back, cool and detached about the lives of others, with few of the psycho-social hang-ups laid bare in Arbus, with none of the frustrated rage barely masked in Winogrand.

New Orleans, Louisiana, 1966

This is (now) the age of the ‘project’, the conceptually driven rather than perceptually driven body of work. Anything which cannot be predetermined, defined publicly prior to shooting, then explicated publicly in a treatise after shooting, is deemed to be substantively wanting and socially suspect, damned by a retrograde tendency to individualism and the private, atavistic doodlings of modernism.

But just a moment. What is a regular, all-American white Joe doing travelling on a coach with a negro jazz band in the late fifties? The saxophone’s wail can touch anyone, but fraternising with black musicians during the Eisenhower years seems to be taking it a little far. At the very beginning of his career, Friedlander has declared a subtle something that is decidedly out of the ordinary. And what of the much mentioned laid-back cool? Who is this spiky haired figure looming up behind an unsuspecting women on a New York street? What about those spreadeagled naked women, or those bleak, unremitting views of working environments? Above all, why the incessant fracturing of the American townscape, with its disturbed reflections and doughboy statues that chase women down sidewalks? Why, for that matter, Haywire Press, Friedlander’s self-publishing company? Just who is this freaked-out, unshaven, unsmiling figure in boxer shorts who stares us down half-dementedly from a hotel armchair? He is a man with as many masks as a Russian doll, masks which he has peeled off gradually over more than twenty-five years, and will no doubt continue to reveal until the last release of the shutter.

As it stands in this exhibition, we have been given a complex and varied portrait of the photographer, more fully rounded than most in photography, and so much more than we might have expected at the beginning – more even than we might have ascertained at the Photographers’ Gallery exhibition fifteen years ago, though that was remarkable enough. In its unassuming, yet assuredly ambitious way, it is a portrait of an extraordinary Joe Average – which in essence we all are. It is a patently truthful portrait, warts and all, consisting of many moods and different levels, varying from the distant and cool to the intimate and warm. And although it has tended to become warmer and more valedictory in its later manifestations, such a progression is by no means certain. We may see this in the nudes, which by virtue of their lengthy gestation, exhibit a wider emotional range than much of Friedlander’s work. The nudes indeed, are positively expressionist if compared say, to the landscapes, laying open a veritable web of feeling, all the mixed-up emotions one might suppose a middle-aged man has had for women since his first infant suck on a teat – desire, fear, awe, loathing, longing, tenderness, rage, lust, and love. They are in there, from one image to another, sometimes with several contradictory moods in one image. Overall – and perhaps this says as much about me as it does about Friedlander – I find the nudes dark, unsettling, disturbing. But I find such undercurrents in much of his work. I would contend that Friedlander is as much of a pessimist, supremely adept at suggesting the creepy side of Middle America, as either Arbus or Winogrand – despite their concentration upon the wilder fringes of society or their adoption of more overtly expressive styles.

Galax, Virginia, 1962

Like a One Eyed Cat is an exemplary, impeccably selected exhibition, and proves conclusively for me that Lee Friedlander is a very great photographer indeed.

Fifteen years ago, I concluded that Friedlander’s work was quintessentially ‘photographic.’ It was, I said:

‘…about photography – not about pseudo-painting, not about graphic schema or chemical manipulation, not about social or political propaganda, not even about itself as an art medium, though it can embrace all of these things – but essentially about the act of taking a photograph, not in a physical but in a psychic sense. It is about the act of seeing, knowing and understanding some small part of the world or fragment of experience, and placing oneself in a singular physical relationship to it in order to make a record of that experience with the camera.’18

I still agree broadly with those sentiments, if not the exact manner in which they were expressed. In essence, they describe what Friedlander has continued to do in the intervening years, demonstrate a central, basic potentiality for the medium. As he has grown older, his photography has grown in complexity and scope to reflect the expanding breadth and depth of his life experience. The work which made his reputation may have become overfamiliar to us through overuse by a legion of followers, but the later mellowing, and now the astonishing, unsettling nudes, prove that he remains well ahead of the game. Like a One Eyed Cat is an exemplary, impeccably selected exhibition, and proves conclusively for me that Lee Friedlander is a very great photographer indeed.

Notes

1. Wallace Stevens, from Not Ideas About The Thing But The Thing Itself, reprinted in Wallace Stevens: Collected Poems (Faber and Faber, London, 1955). Page 534.

2. Gerry Badger, Lee Friedlander, in The British Journal of Photography (London), March 6, 1976. Pages 198-200.

3. Lee Friedlander, Like a One Eyed Cat (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1989).

4. Lee Friedlander, Nudes (Museum of Modern Art, New York, and Jonathan Cape, London, 1991).

5. Lee Friedlander, The American Monument (The Eakins Press Foundation, New York, 1976).

6. Lee Friedlander, Trees and Flowers (Haywire Press, New City, N.Y., 1981).

7. Lee Friedlander, Portraits (New York Graphic Society, Boston and New York, 1985).

8. See Lee Friedlander, Factory Valleys (Calloway Editions, New York, 1982), and Cray at Chippewa Falls (Cray Research, Inc., Minneapolis, 1987).

9. Badger, op. cit., page 200.

10. Martha Rosler, Lee Friedlander’s Guarded Strategies, in Artforum (New York), April 1975. Page 47 and page 52.

11. John Szarkowski, quoted in Rosler, op. cit., page 47.

12. John Szarkowski, wall note to Lee Friedlander: 50 Photographs, shown at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, from October 20, 1974, to January 30, 1975.

13. Lee Friedlander, quoted in Nathan Lyons, Toward a Social Landscape (Horizon Press, New York, and George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, 1966). Page 7.

14. Ingrid Suschy, quoted in Nudes, op. cit., unpaginated.

15. Factory Valleys, Op. cit.

16. Leslie George Katz, ibid., unpaginated.

17. From February 28 to May 7, 1967, the work of Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Diane Arbus was introduced together in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, entitled New Documents, setting the standard for a new notion about the ‘documentary.’ In his wall label for that exhibit John Szaskowski wrote, ‘In the past decade a new generation of photographers has directed the documentary approach toward more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life, but to know it.’

18. Badger, op. cit., page 199.

ASX CHANNEL: Lee Friedlander

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

(Text Copyright © 1991 Gerry Badger. All rights reserved. All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher.)