For Avedon’s program is supraindividual. He wants to portray the whole American West as a blighted culture that spews out casualties by the bucket: misfits, drifters, degenerates, crackups, and prisoners-entrapped, either literally or by debasing work.

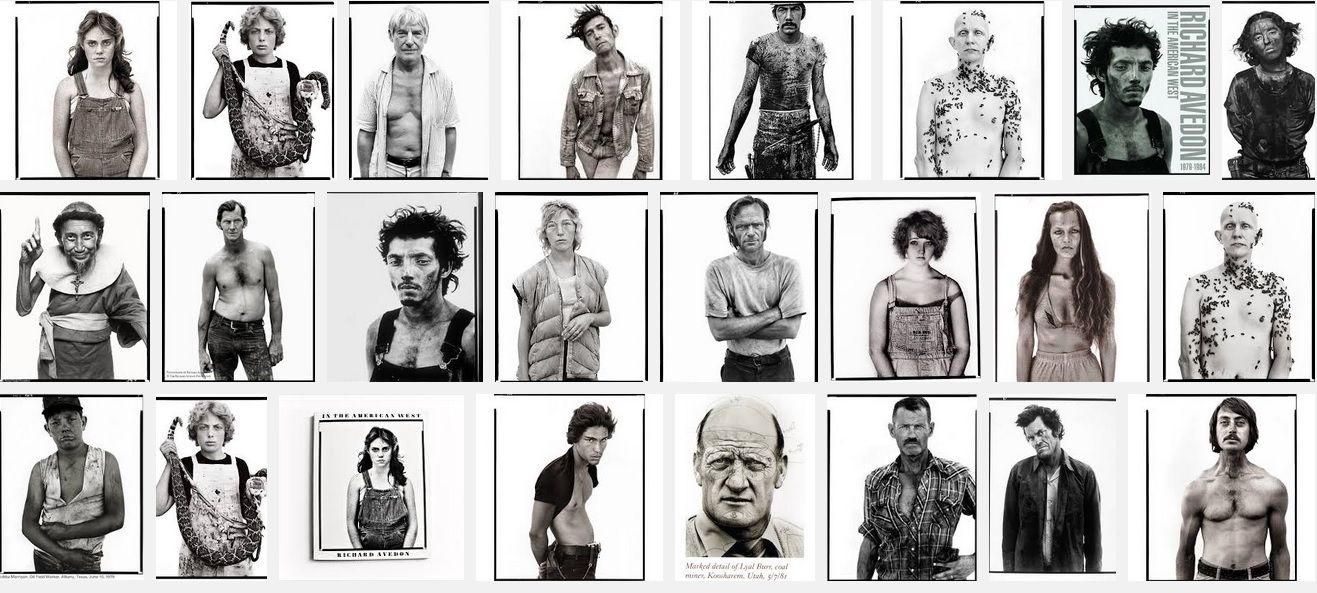

Richard Avedon’s “In the American West”

By Max Kozloff

“Sometimes I think all my pictures are just pictures of me. My concern is… the human predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may simply be my own. ” – Richard Avedon

No one has smiled in an Avedon portrait for a long time. If there was pleasure in their lives it left them in the act of posing, or rather, confronting his lens. One sitter, de Kooning, told Harold Rosenberg that Avedon “snapped the picture. Then he asked ‘Why don’t you smile?’ So I smiled but the picture was done already….” The photograph of de Kooning and the quote appeared in Avedon’s Portraits (1976), an image-gallery of famous people in the arts and media. A disproportionate number of them look either snappish or torpid and tired… oh so tired… unto death.

At the end of that book, in a suite of shots that record the progress of his father’s cancer, the subject is described as literally wasting away. But this is a progressive account not so much of the flesh dying off, but more of his father’s terrified knowledge of his decomposition – a conclusive rush of dismay that gives Portraits its unstated theme.

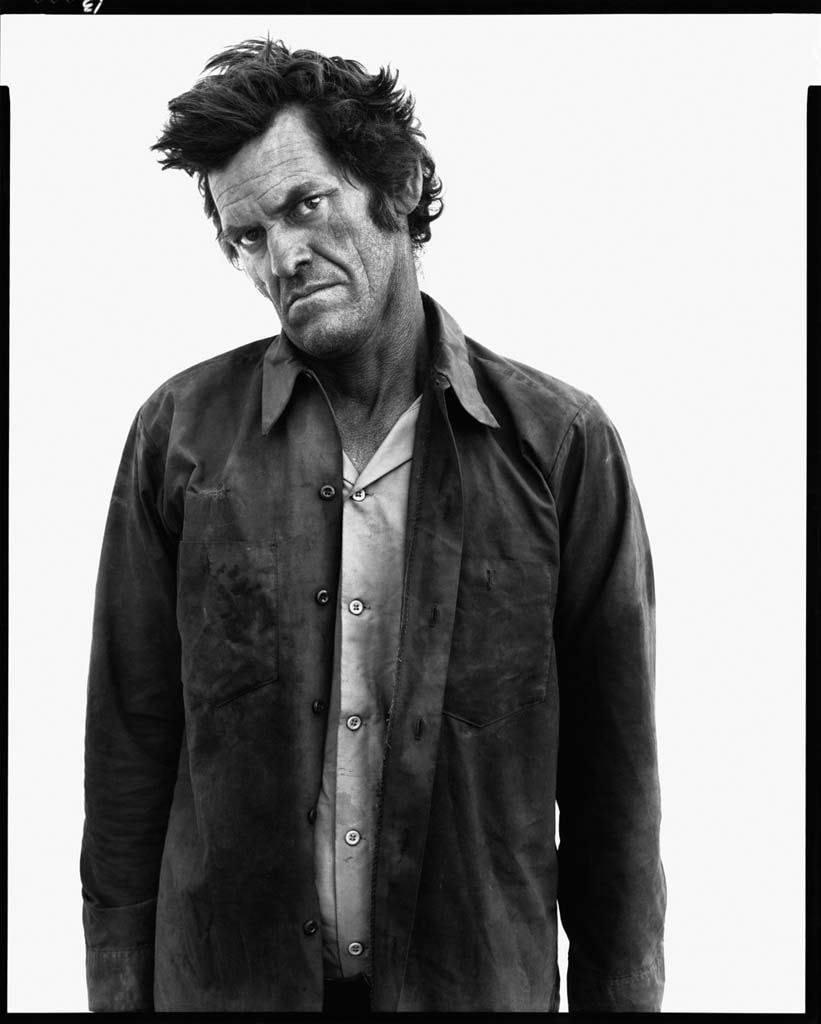

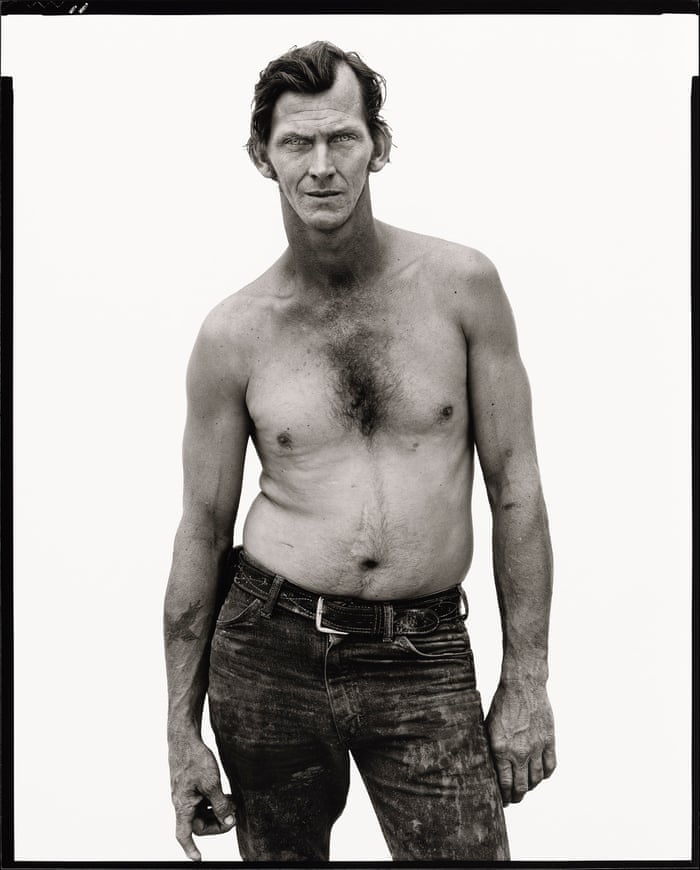

Avedon’s most recent portrait effort, In the American West, published by Abrams in 1985, furthers that theme, once again by a characteristic emphasis at the end of the book. There, in studies of slaughtered sheep and steer, he insists upon such details as glazed and sightless eyes, blood-matted wool, and gore languidly dripping from snouts. As his father was the only unprominent person in the first campaign, so the animals are the only nonhuman subjects in the second. It’s as if Avedon were each time underlining his philosophy by breaking his category. Adjoining the guignol presences of the animals are ghoulish images of miners and oil-field workers, as befouled by the earth as the animals by their spilled entrails.

For Avedon’s program is supraindividual. He wants to portray the whole American West as a blighted culture that spews out casualties by the bucket: misfits, drifters, degenerates, crackups, and prisoners-entrapped, either literally or by debasing work. Pawns in his indictment of their society, his subjects must have thought they were only standing very still for the camera. Even those few in polyester suits who appear to have gotten on more easily in life are visualized with Avedon’s relentless frontality and are pinched in the confined zone of the mug shot. In photography, this is the adversarial framework par excellence. He could rely on knowledge of this genre to drive home the idea of a coercive approach (which he frankly admits), and of incriminated content. But why should he have imitated a lineup? And why, since this is his personal vision, should he refer to an institutional mode?

The blank, seamless background thrusts the figures forward as islands of textures of flesh, certainly, but also of cloth. Nothing competes with the presentation of their poor threads, nothing of the personal environment, nothing that might situate, inform, and support a person in the real world, or even in a photograph.

The answer to these questions should probably be sought in the politics of Avedon’s career, or rather, his career in the politics of culture. With him, style has always been understood as political expression, and the will to style but a reflection of the will to power. Translated into photographic terms, this becomes a matter of visually phrasing the relations between the subjects and the photographer. For example, either the sitter can be depicted as apparently possessing the means to act freely, or the photographer can be perceived as free in the exercise of control over others. In his fashion work for over thirtyfive years, Avedon configured the myth of the hyper-good life of the ultramonied in the bright expressions and the buoyant gestures of expensively outfitted women who flounce through a blank or glittering ambience where there is always enough room for them to open their wings, even in close quarters. No one had more success in vectoring the physical ease with which splurge maneuvers. No one could fake a more lacquered spontaneity. Unquestionably Avedon called the shots in the studio, but his was the kind of work in which mastery nevertheless had to disguise itself, hold itself in check.

Though they were literally his creatures behind the scenes and in the throes of picture production, the fashion models were imaged to have a magnetic, even commanding effect. The conceit of the genre asserts that subjects are constant narcissists and photographers are professional adorers. Fabricated through the collective resources of a large and nervous industry, the final spectacle, a self-centered object of regard, was something that existed only to lift up and draw in the gaze of the viewer. The high-fashion photograph mimics a situation in which the viewer is supposed to be captivated by styles of material display. Of course its commercial message was thoroughly bonded to the psychic lure and social symbolism of the picture. All those with craft input into the fashion image were contributing to a mercantile semblance of a court art in a democratic society.

Avedon did nothing so crass as to intimidate his subjects since it was much simpler and more effective to put forth his indifference to the portrait contract itself. While depicting people, his portraits carry on as if they were describing objects of more or less interesting condition and surface.

In the late forties and early fifties, there developed an American market for an idiom of literal swank and sniffishness. Avedon led the way in adapting this largely continental mode more appropriately to our manners. He made his figures approachable, innocently overjoyed by their advantages, as if they were no more than perpetual young winners in life’s lottery. It was Avedon, too, who set the pace for contemporary narrative scenarios of fashion display. Into the sixties he managed to waft via the faces of his mannequins the sense that their good fortune had hit very recently – say the second before he opened the shutter. When unisex became chic, and fetishism permissible, he filtered some of their nuances into his design. He could also suggest that the glamour of his models drew the attention of sports and news photographers, whose styles he sometimes laminated onto his own. (This was a snap for someone who grew up on Steichen and Munkacsi, and knew about Weegee.)

Insights into the crossover of genres and the convergence of modern media gave Avedon’s work its extra combustive push. He got fame as someone who projected accents of notoriety and even scandal within a decorous field. By not going too far in exceeding known limits, he attained the highest rank at Vogue. In American popular culture, this was where Avedon mattered, and mattered a lot. But it was not enough.

In fact, Avedon’s increasingly parodistic magazine work often left -or maybe fed- an impression that its author was living beneath his creative means. In the more permanent form of his books, of which there have been five so far, he has visualized another career that would rise above fashion. Here Avedon demonstrates a link between what he hopes is social insight and artistic depth, choosing as a vehicle the straight portrait. Supremacy as a fashion photographer did not grant him status in his enterprise -quite the contrary- but it did provide him access to notable sitters. Their presence before his camera confirmed the mutual attraction of the well-connected.

Unlike the mannequins, most of the sitters had certified personalities, and this perked up Avedon’s interpretations with extra dividends of meaning. The early portraits worked like visual equivalents of topics in the “People are talking about . . .” section in Vogue; they fluttered with cultural timeliness. When he showed Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller lovingly together, it was as if each of them took manna from the other in a fusion of popular and highbrow icons. The first book, Observations (1959) with gossipy comment by Truman Capote, spritzes its subjects with an almost manic expressiveness. They are engaged at full throttle with their characteristic work, so that the contralto Marian Anderson, for instance, has a most acrobatic mouth. These pictures were engendered well within the fashion mold (publicity section), but they led gradually to a break into a new, anxious politics of the image.

Avedon’s second book, Nothing Personal (1964), tries to evoke something of its historical moment, although it would seem hard to suggest the duress of the sixties through portraits alone, even when arranged in narrative sections. It opens with foldout tableaux of wedding groups, in which a number of ordinary people rehearse their festiveness, as if they were models. There after, we get sitters known for ideological heaviness, positive or negative depending on the readership: the Louisianian politician Leander Perez, George Lincoln Rockwell, Julian Bond, and so on. They scowl, salute, or look clean-cut; that is, they are made to impersonate their media image with breathtaking simplicity and effrontery. One symbol is assigned per person, and one thought is applied per image. Almost at the end, Avedon treats us to a group of harrowing, grainy action closeups of inmates in madhouses, and he concludes the book with happy beach scenes.

Just the same, the western album is his most arresting book. I am thoroughly downcast by his terrible perspective on the West, but that is his right.

These wild technical and mood swings are worked up in a jabbing, graphic magazine-like layout, as if Avedon thought that a book audience had as short an attention span as a fashion-mag public. One gets the strange feeling that while the illustrations are present, the feature articles are absent. In their place is an essay by James Baldwin, at his most self-indulgently alienated and bitter. Not only does his prose fail to mention the pictorials, it has nothing to do with them, regardless of the occasional avowed racists Avedon depicts. There is something half-baked about the way the book seeks to move visually from the emphatic trifles of the fashion media to the “relevance” – a word then in great currency of political statement.

Baldwin lashes out at the unmitigated nastiness of the American scene, but Avedon does no such thing. This impresario of haute couture at Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar lacked the credentials to offer any sort of critique from below. Even when it would seem to be suggested by a tendentious icon, there was no moral energy in his outlook. We’re in a world only of angles, not of values. The book offers an uneasy sequence of sentimental, tart, sycophantish, and pitiless images. A group portrait of D.A.R. officials comes on simultaneously as a takeoff from Irving Penn’s Twelve Most Photographed Models (1947) and as a satire on genealogical arrogance, but is too respectful to succeed on either count.

One of the most vivid faces in the history of portraiture is also here, that of William Casby, an ex-slave. One of the most significantly disturbed personalities in our post-World War II history, Major Claude Etherly, bombardier of the Enola Gay at Hiroshima, makes an appearance, though he does not create an impression. Nothing Personal certainly grabs one’s attention, but it doesn’t add up. It’s so busy figuring out its strategies that it gives the reader the idea that Avedon had no time to respond to anyone. Much of the album assumes a clarity of purpose that is not realized in a design chopped up by willful and unexplained thematic jumps.

Like crossed wires, the messages in this curious album seem to have shorted out. Thereafter, we no longer see a rhetoric infused through the junction of image-sets or portrait scenarios. Strangely enough, such a liberation does not appear to have refreshed his sitters. A pall now generally falls over them, and their body language is constrained to a few rudimentary gestures. Avedon, in fact, would take the portrait mode into a new, antitheatrical territory. Visualized from familiar rituals of self-consciousness and self-scrutiny, portraits offer specific moments of human presentation, enacted during an unstable continuum. Whatever their apprehensions, sitters hope to be depicted in the fullness of their selfhood, which is never less than or anything contrary to what they would be taken for (considering the given, flawed circumstances). What ensues in a portrait is usually based on a social understanding between sitter and photographer, a kind of contract within whose established constraints their interests are supposed to be settled. In his fashion work, Avedon dealt with models whose selfhood had been professionally replaced by aura. His career was a function of that aura. Presently, engaged with sitters, he found that their selfhood could become a function of his aura.

Avedon did nothing so crass as to intimidate his subjects since it was much simpler and more effective to put forth his indifference to the portrait contract itself. While depicting people, his portraits carry on as if they were describing objects of more or less interesting condition and surface. Though this deflates his subjects, such a radical procedure is just as evidently not hostile… not, at least, consciously hostile. Nothing Personal anticipates the route Avedon was to follow, and is already aptly named. Portraits, a much later book (1976), gets very close to its subjects in terms of physical space and is now decisively removed from them in emotional space. The noncommittal titles of these projects are ideological clues intended to suggest the absence of individual bias.

Many of the details in these newer portraits are very articulate socially and culturally, but the visualizing instinct behind them is certainly opaque. The photographer wants to do justice to the presence of the sitter, at that particular moment, though only insofar as he can make a certain kind of Avedon picture, or cause a sensation. (Ideally, the two would go together.) Avedon demonstrates such a long-term superiority in the contest of wills in portraiture that even the occasional assertiveness of a subject does not compromise the unconcernedly abusive look he had begun, in the sixties, to achieve and be known for. For all that they are sentient and experienced people, his subjects consented to exposure since it was still hard to imagine anyone like him taking their feelings so little into account. The contrast between what is presented and how it is processed generates the unsettling effect of the Avedon portrait. Let there be no mistake, that effect is here the equivalent of intended content.

As he introduces the western gallery, Avedon writes, “The moment {a} fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.”

Harold Rosenberg spoke of Avedon’s “objective cruelty” (when photographing Warhol’s scars), and then went on to write of the photographer as a difficult, reductionist artist, like Newman or Still. This is spectacularly wrong, since it implies that Avedon wanted to practice an ideal, difficult truthfulness, whereas he’s a most equivocal, advantage-taking realist, and knows it. As he himself says about the western portraits: “Assumptions are reached and acted upon that could seldom be made with impunity in ordinary life.” The big 8-by-10-inch camera is, then, an alibi for a most transgressive stare. Such a stare doesn’t come from painting, of course, but it does stem from a knowledge of the German August Sander, whose catalogue of social types Avedon makes much harder edged, and of Diane Arbus, whose ecstatic, guilty transgressions Avedon routinely refrigerates.

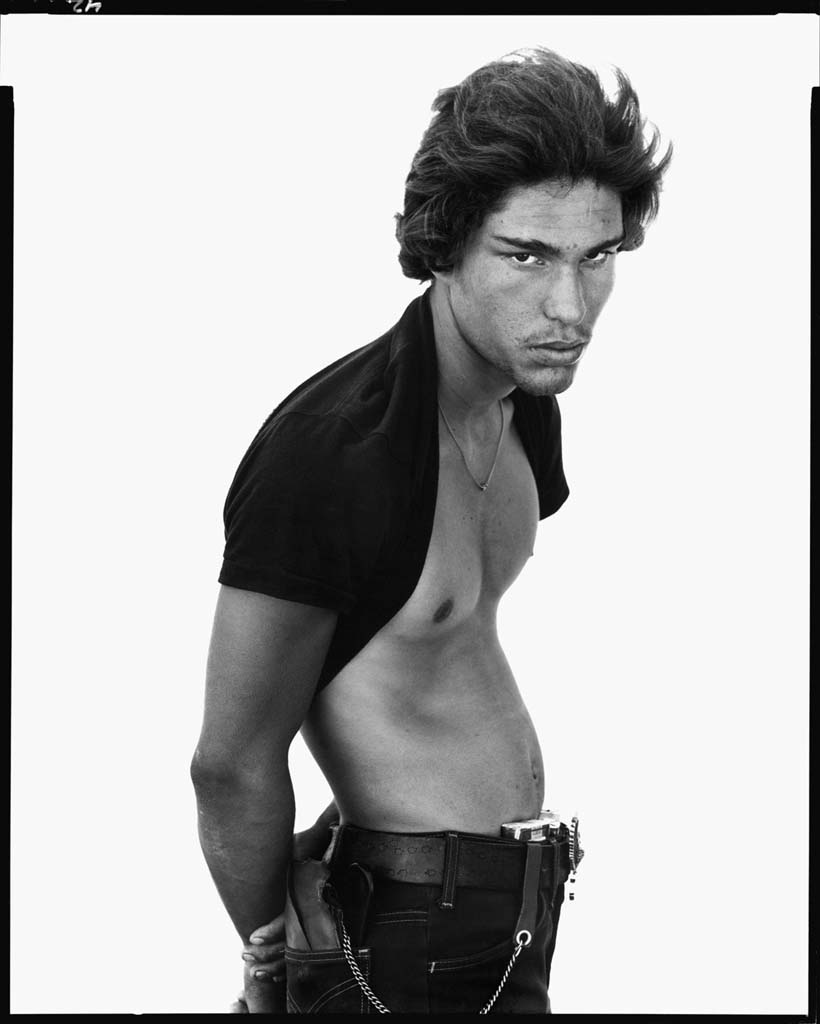

An assumption of extreme, hard-headed realism is brandished through Avedon’s portrait work. There is, for instance, the highly specific dating of these pictures, as if the day as well as the year of exposure mattered. This is extra, inessential information – and quite typical of a realist attitude. Then, too, one notices the clinical approach, the pronounced, unshaded clarity of sight and the emphasis on physical data. Further still, if Avedon’s glamour imagery was known to be highly fictive, then his realist portraiture, through an altogether mechanical turn, would have to stand for everything unglamorous. In his recoil from the sentimental, Avedon hardly stops anywhere along the line until he gets to the unsparing and pugnacious. Even his young westerners seem to have a meanness knocked into their faces and only a bleak life in the future. Realists are thought to look the world unflinchingly in the face, and their credibility is supposedly increased the more imperfections they record.

In realist territory, Avedon had to compensate for his well-earned reputation for smart, commercial stagecraft, and he protests, accordingly, in the hands-off direction of these “dumb,” do-nothing poses. The subjects are understood to be engaged with (or are caught in) nothing more than an unschooled or archaic attempt to comport themselves, which they more or less fumble, thus revealing their actual character.

But the question remains: what is convincingly revealed in these images? I, for one, am persuaded of the grumpiness of most of the sitters at the moment they were photographed. One sees this expression often in photographic culture, when people aren’t getting help from the stranger behind the camera, and don’t know why he should be trusted. It’s a kind of squint, and it hardens them. In a book containing I06 pictures of westerners, this arid psychological atmosphere prevails so completely that it rules out the freshness of any open, one-to-one human contact. The subjects are individuated according to their varied circumstances and histories, but not by their moods. Whatever public foreknowledge might have made it difficult for Avedon to obtain his results in his own social circles during the first half of our decade, they could be brought off more easily among any group unaware of his national reputation, such as these somewhat defensive but unsuspecting westerners. Their need to plead their case went deeply, he says, but “the control is with me.” If his insistence upon this control is necessary to legitimate himself as a realist artist, no matter at whose expense, he nevertheless fails to accomplish realist art.

Again, his sophistication about photographic pictures prepares him to encompass and accept this judgment. As he introduces the western gallery, Avedon writes, “The moment {a} fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.” How remarkable that his critics have not thought to quote him a little further on in this statement, where the deep, internal conflict of Avedon’s portraiture asserts itself. On one hand, he arranges it so that the sitter can hardly shift weight or move at all, supposedly because the camera’s focus won’t allow it. The hapless subject has to learn to accept Avedon’s uncompromising discipline (as if the lens and the photographer were the same). On the other hand, “I can heighten through instruction what he does naturally, how he is.” In the end, “these strategies . . . attempt to achieve an illusion: that everything . . . in the photograph simply happened, that the person . . . was never told to stand there, and . . . was not even in the presence of a photographer.”

One either remains speechless upon reading this total denial of his working program in the American West, or one sees that it applies covertly to fashion photography. Such stridently mixed signals and elemental confusion about self-process have something to say to us about the derisive qualities of the work itself. I think not only of the fact that voyeurism is the chic metaphor in fashion (none of the models are supposed to be aware of the photographer), but also that fashion has always been an imagery of material display -and that’s what Avedon’s western portraiture consciously amounts to. The blank, seamless background thrusts the figures forward as islands of textures of flesh, certainly, but also of cloth. Nothing competes with the presentation of their poor threads, nothing of the personal environment, nothing that might situate, inform, and support a person in the real world, or even in a photograph. At the same time, the viewer is left in no doubt about the miserableness and tawdriness of their lives- for their dispiriting jobs or various forms of unemployed existence are duly noted. An ugly comparison is invited between all these havenots and Avedon’s previous and much better defended “haves.” It is one thing to portray high-status and resourceful celebrities as picture fodder: it is quite another to mete out the same punishment to waitresses, ex-prizefighters, and day laborers.

Where is the moral intelligence in this work that recognizes what it means to come down heavy on the weak? Even the thought that such hard luck cases might arouse class prejudice does not surface in the book’s text. All that would be required for “polite” society to imagine these subjects as felons would be the presence of number plates within the frames. In the mug shot, the sitter’s selfhood is replaced by an incriminating identity in a bureaucratic system. Avedon has gained a cheap, enduring dominion over his sitters by reference to this mode, but executes his pictorial versions of it very expensively, and therefore, innovatively. He not only used a view camera of much greater optical potency than needed and exposed around 17,000 sheets of film in “pursuit of 752 individual subjects”;(1) he also enlarged his photographs to over life-size and had them metal-backed for exhibition in art galleries and museums. The disproportion, technical overkill, and sheer obsessional freakishness of this campaign work as factors of stylistic insistence. And without question, he succeeded, for one can definitely recognize any of these pictures as an Avedon at sixty paces.

For fashion photographers, the problem of “saying” something, of having any conceptual obligation to picture a world, is solved before any film is exposed; they know who the client is. The action and the enjoyment of fashion photography is bound up entirely with distinctions of craft, flair, and setting – the equivalents in their commercial context of imaginative vision in an artistic one. For all their harshness, Avedon’s portraits belong to the commercial order of seeing, not the artistic.

Pictures may be only their mute selves, but for Avedon they are everything, a totality. The photographer thinks that you ultimately get to know people in pictures, as if there is some arcane, yet clinching knowledge to be gleaned from the image.

Just the same, the western album is his most arresting book. I am thoroughly downcast by his terrible perspective on the West (in a background text Laura Wilson, his assistant, more or less implies Avedon’s special receptivity to damaged subjects), but that is his right. Obviously, whole spheres of western culture – the sun-belt retirement communities, the new wealth grown up through oil and computer development, the suburban middle class -are ignored in Avedon’s gallery. He is definitely obsessed by a myth based on geographical desolation, rather than engagement with any real society. Just the same, those who complain about his unfair visual sampling are quite off the mark; let them tell us what sampling is fair. But if I ask what is the principle of this sampling – for example, personal animus, political critique of western culture and conditions, or humanist compassion for social casualties – I don’t get any legible reading at all, and suspect that there isn’t one. It’s not that the subjects don’t incite judgment or sympathy – they do that automatically because they’re human and we’re human. Rather, Avedon counts on their shock value, on this level, to get us absorbed by the way they look.

It’s certainly true that the picture of the blond boy exhibiting the snake with the guts hanging down is a sensational image. Likewise, the hairless man literally coveted with bees. And who can forget the Hispanic factory worker with the crisp dollars cascading down her blouse, or the unemployed blackjack dealer, with a face made of dried leather and bristle, whose sport jacket is a tantrum of chevrons? Nothing seems to come out right in these faces, and so many others, that have a breathtaking oddness. They make terrific pictures. In 1960, Avedon did a real mug shot of the Kansas murderer Dick Hickock, protagonist of Capote’s In Cold Blood. He printed it next to a larger one of Hickock’s father (taken the same day), in the Portraits book. Here is some evidence of an avid look at the genetics of American faces for whatever might be reckoned as pathological in them. In the current gallery, that pathology seems to have come home to roost, at such close graphic quarters that it’s a relief to know that these are only pictures, and the subjects won’t bite.

Pictures may be only their mute selves, but for Avedon they are everything, a totality. The photographer thinks that you ultimately get to know people in pictures, as if there is some arcane, yet clinching knowledge to be gleaned from the image. Strangely enough, it had been the inadvertent resemblance of his earlier western portraits to nineteenth-century ones that led the Amon Carter Museum of Fort Worth to commission Avedon to do this series. If any such work is recalled to me, it would be medical photography of the last century. Doctors had sick people photographed to exhibit the awesome hand of nature upon them. Later, the subject might be lesions.

Avedon photographs whole people in the “lesion” spirit. In the New York Times of December 21, 1985, he asked, “Do photographic portraits have different responsibilities to the sitter than portraits in paint or prose, and if they seem to, is this a fact or misunderstanding about the nature of photography?” Well, if he had to ask, the question certainly indicates his misunderstanding of the medium. But more than that, the question symptomizes a failure of decency that no amount of vivid portrayal will ever redeem, because the portrayal and the failure are bound together in the malignant life of the photograph, each a reflection of the other.

In the American West.

Photographs 1979-1984.

Photographs by Richard Avedon. Preface by John Rohrbach. Foreword by Richard Avedon. Background by Laura Wilson.

Harry N. Abrams, New York, 2005. 184 pp., 120 tritone illustrations, 11×14″.

(© Max Kozloff. All rights reserved. All images © copyright The Richard Avedon Foundation.)