By Simon Baker, Brought to ASX by 1000 Words Magazine, 2010

There is a partially obscured photograph of the French writer Georges Bataille in Leigh Ledare’s Double Bind: just one of a number of ripped-out book and magazine pages that make up collage elements in a diverse installation of different kinds of photographic image; made, found and arranged, by the artist. Bataille, the anti-surrealist so-called ‘shit-philosopher’, was described by his friends as ‘impossible’: the impossible Bataille balanced a day-job in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France with night-time brothel culture; wrote scholarly essays on coins, and some of the most subversive and explicit novels ever published: the manuscript for his infamous Story of the Eye, having in fact been scribbled directly on the backs of library record cards, as though he’d written it at work. The ‘impossible’ Bataille, whose interest in eroticism and transgression stretched from theory to practice, seems an appropriate figure to find at the heart of Ledare’s work, which seems constantly to take issue with what it is possible to photograph.

Visitors to Arles in 2009 will have seen an installation from a body of work called Pretend You’re Actually Alive, in which Ledare engaged with an impossible, (and impossibly intimate), subject; working with (and against) his own mother as she herself worked in and around the production of pornographic films and photography. Images of her current activities and collaborators, inter-cut with sombre, restrained portraits, images from her former life as a young ballerina, and intimate documentary evidence of her complex, powerful but strained relationship with her children. The impact of this installation at Arles, (and again when shown at Pilar Corrais gallery in London in 2010), was two fold: brutal and immediate, prompting an immediate head-shaking refusal to accept the troubling and explicit content, coupled with a slow-burning realisation that despite this impossible material, the rhetorical presentation of the material was precisely calculated and incredibly sophisticated. It is the ability to achieve this impossible equilibrium between form, (or rhetorical address), and content, that marks Ledare out as one of the most engaging and original artists working with photography at the moment. And this intellectual tactical facility with framing and presenting material of intense emotional and personal significance is evident not only in the gallery installations of the work, but in the publication Pretend You’re Actually Alive, produced by Andrew Roth/PPP in 2008, and already recognised as one of the most significant photo-books of recent years.

Another thing that Ledare has in common with Bataille, however, is his ability to reach through the carefully calibrated rhetoric of presentation to a genuine emotional affect: Bataille sought, after all, to unpick the conventional relationship between the mannerism of cultural production and the emotional urgency necessary for its consumption. His response to the work of Salvador Dali, for example, was to suggest ‘squealing like a pig’ before his canvases; and his challenge to collectors of Picasso was to point out that they could never ‘love’ one of his paintings as much as shoe-fetishist loved a shoe. The obsessive, urgent, involuntary response, (something that should by rights have been repressed) had to be more honest and of more value than some bland, tasteful, sense of ‘appreciation’. And it is in this preservation of affect (the communication of an intense emotional intelligence as emotion, rather than intelligence) that can also be found in Ledare’s work: this is photography at the limit of propriety and therefore photography that risks upsetting the mannered conventions of conceptual post-rationalisation (in itself a very good thing at this point in time).

However, having made as significant and as effective a body of work as Pretend You’re Actually Alive, there was always going to be a question over what could possibly come next. The collapse of eroticism with the maternal (also, incidentally, celebrated by Bataille), seemed to be something of a final taboo, or at least a point beyond which it seemed there might be little further emotional terrain left to explore: as one well-known photographer remarked of Ledare’s work – ‘how on earth can you follow that!’ – a sentiment as pertinent to Ledare as the person who expressed it. So showing a new body of work, similar in scale and complexity to Pretend You’re Actually Alive at Arles this year, 2010, was inevitably both a challenge and a risk for Ledare. And although he did not leave the previous body of work entirely alone (showing one of the film sequences of his mother that he had added to the London installation of Pretend You’re Actually Alive), the new work, Double Bind did indeed offer something entirely different, while remaining true to the impossible negotiation of emotional honesty and rhetorical complexity in his work to date.

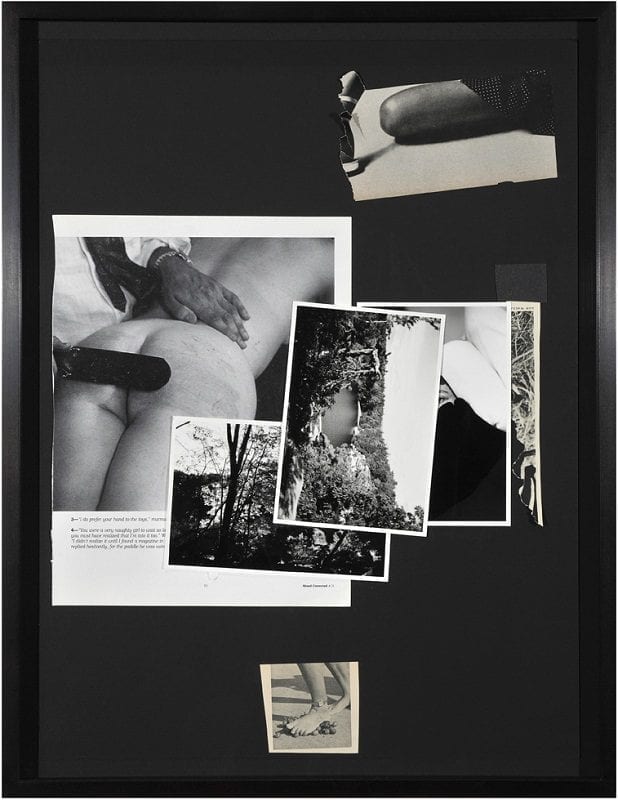

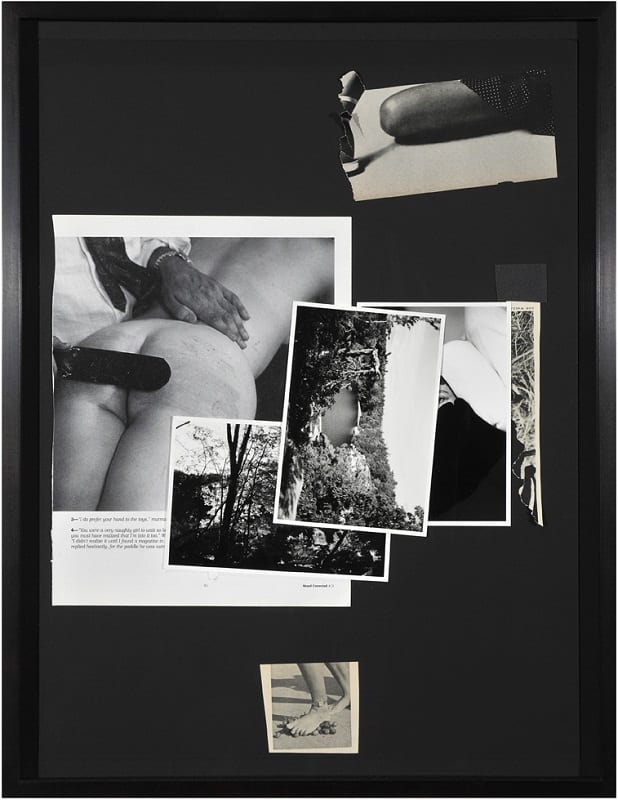

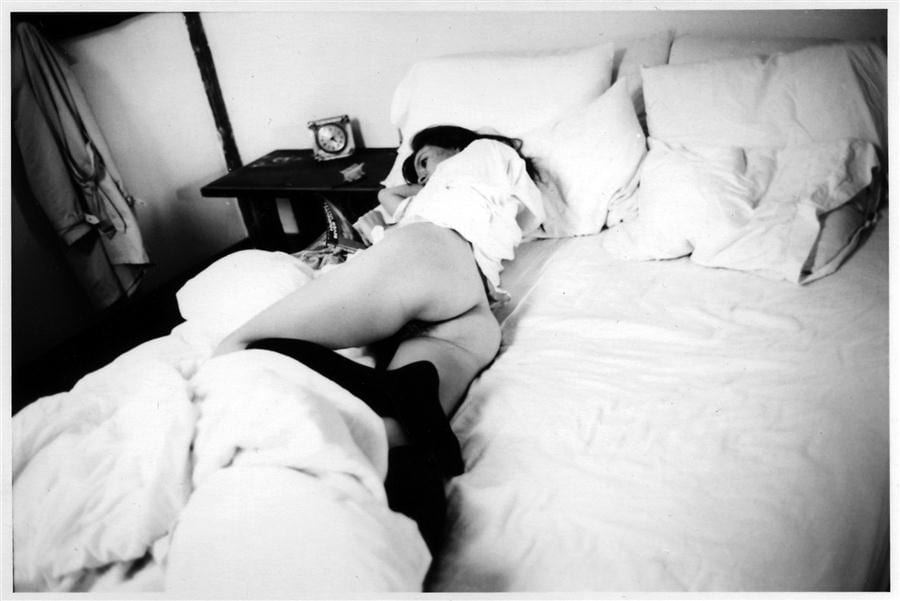

Remaining close to home, for Double Bind, Ledare worked with his recently re-married ex-wife Meghan Ledare-Fedderly, and her present husband, the photographer Adam Fedderly, placing the three of them within an elaborate, and presumably uncomfortable, set-up. The original premise for the work, the ‘double-bind’ of the title, was that Ledare would visit a remote country cabin with his ex-wife, photograph her there for several days, and then ask her to return to the same place with her current partner and repeat the experience, with Fedderly giving up the unexposed rolls of film to Ledare on their return. Ledare took responsibility for printing both sets of photographs by hand so that the immediate results of this doubled process were two substantial sets of strangely intimate, (and stranger still), and strangely similar, small-scale black and white prints. For Ledare; ‘The images suggest a phenomenological comparison of Meghan Ledare-Fedderly as observed from the vantage of two distinct relationships…the newlywed associated with limitless potential, and [his own], an exhausted, finite version of this same role.’ And this sense of comparison is heightened in the work itself, with examples of Ledare’s and Fedderly’s photographs of their ex-wife and wife (respectively), hung side by side, framed on the gallery walls. But for the final installation of Double Bind these prints also took their places within a much more complex collection of Ledare’s personal belongings: images from his past, presented in the form of collages and displays, including both intimately sentimental, and explicitly pornographic material, as well as obscure (and obscured) cultural references like the portrait of Georges Bataille.

The way that the images of Meghan Ledare-Fedderly take their place within the complex structure of Double Bind is, unsurprisingly, hugely significant: clearest perhaps in strange double-bind between, on the one hand, those pairs of images that look indeterminably similar (where the gaze that strikes the two photographers lenses seems equivalently tender or malevolent); and on the other, moments of irreconcilable difference, where images of impossible physical intimacy sit side by side with images of concealment or evasion.

As with Pretend You’re Actually Alive, there is a balance struck between the expression of raw emotion and its rhetorical choreography within the display. Or, to put it another way, there is a double-bind generated within the work: the desiring look within the image (whether in response to Ledare’s ‘exhausted’ vision or the ‘limitless potential’ of Fedderly), doubled by the desire of the viewer to determine the nature of the gaze through Ledare’s careful orchestration of the images themselves. There are individual examples of pairs of photographs framed on the walls where this dynamic works extremely well, but it is in a pair of glass-topped tables, containing grids of archive stacks of ‘unused’ prints (from Ledare and Fedderly respectively), that Double Bind becomes truly impossible. It seems here that a body of work which, it might be imagined, would have generated nothing but contrast, conflict and opposition, has, at the same time (involuntarily) generated its own centrifugal force: a kind of emotional-representational entropy, through which every additional image of Meghan Ledare-Fedderly tends towards the same impossible conclusion. Double Bind, then, may deal with a more subtle and equivocal subject than Pretend You’re Actually Alive, but with this new work Ledare continues to demonstrate a singular commitment to the equivalence of the conceptual rigour of image-rhetoric, and direct emotional engagement. This uncomfortable but productive position, it would seem, is one that photography has always been capable of occupying but has rarely achieved.

At a moment of considerable pessimism in 1930, Georges Bataille wrote The Modern Spirit and the Play of Transpositions; the text that includes his famous ‘shoe-fetish’ challenge, and which was illustrated by bizarre photographs of dead flies. In it he suggests that the increasingly complex rhetorical presentation of subject matter (like the florid arrangements of bones in the catacombs), was all that there was left to art: with artists doomed to occupy a depressing conceptual impasse, manipulating and transforming what he called the ‘sad fetishes’ destined to move us, (a description, that may well be more apposite now than it was then). But the conclusion to Bataille’s essay suggests something like a way past this dead-end, in the form of works of art that are, as he puts it; ‘addressed just as much to the taste of informed enthusiasts as to the most unfortunate or hidden emotions of humanity.’ This, it would seem, given the evidence of Ledare’s work, is still a double-bind worth entering into.

Simon Baker is Curator of Photography and International Art at Tate. He is Tate’s first curator of photography and joined in 2009 from the University of Nottingham, where he was Associate-Professor of Art History. He has researched and written widely on surrealism, photography, and contemporary art; and co-curated the exhibitions Undercover Surrealism: Georges Bataille and Documents (Hayward, London: 2006) and Close-Up: Proximity and defamiliarisation in art, film, and photography (Fruitmarket, Edinburgh: 2008).

[nggallery id=396]

ASX CHANNEL: Leigh Ledare

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher