Parlourmaid and underparlourmaid ready to serve dinner, Mayfair, 1936

Bill Brandt enjoys darkroom work and likes to experiment, printing the same shot in several different ways. ‘It takes a long time to produce a good print.’ No mass production.

Creative Camera Owner Magazine, 1970s

Bill Brandt’s landscapes are truly creative. He went to the same places that had been photographed many times before-but he saw differently and set a standard that has rarely been equaled, never surpassed. His simple, open ‘scapes have a mysterious brooding beauty that is unique, yet widely imitated. But such masterpieces do not come easily. He has infinite patience and will wait months, years, for the right weather, the right season, the right combination of circumstances that will present him with the picture he knows to be there.

The Nudes

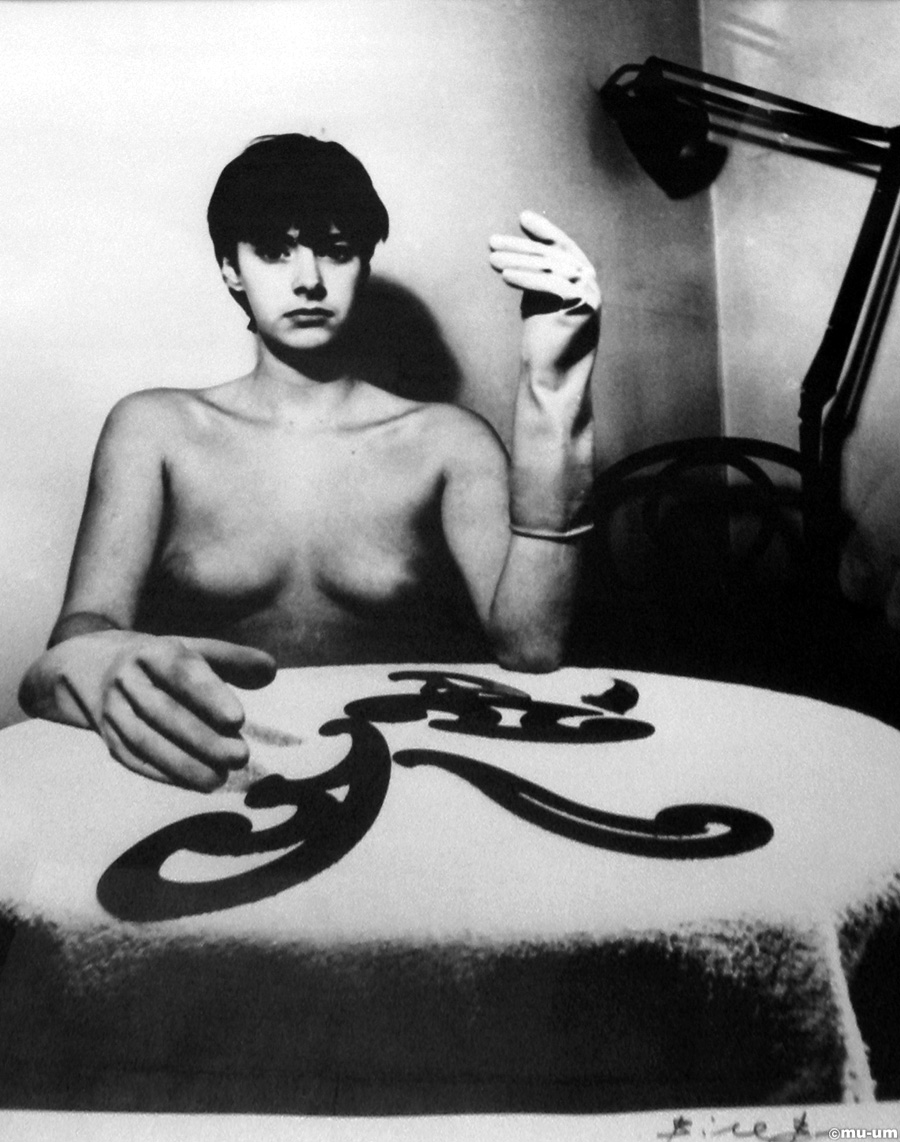

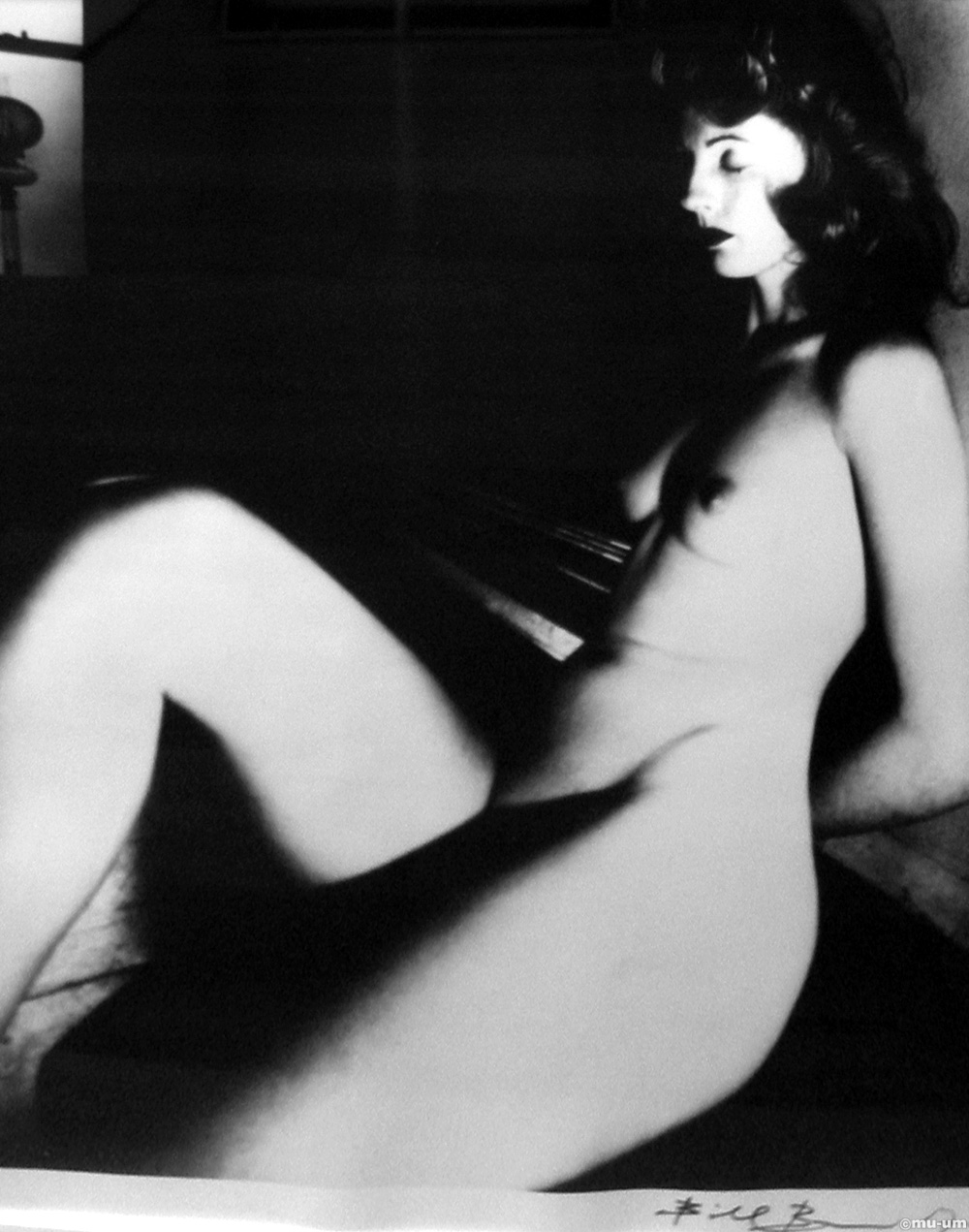

Since 1945, too, he has created a magnificent series of nudes, which are a significant landmark in the evolution of the photographic nude. His series was started in 1945 with the discovery of a camera that would give him ‘an altered perspective and a less conventional image’ that would help him to see ‘like a mouse, a fish or a fly’. It came in the form of an old mahogany monster created by Kodak. It had no shutter, the aperture in its wide-angle lens was as small as a pinhole, and it was permanently focused on infinity. It had been used by Scotland Yard for police record work and by auctioneers to make inventories. He loaded the camera with a fast film, and started experimenting. The image on the ground glass was so dim it was useless for pre-planning the picture. The camera had to do its own seeing. Each exposure was a gamble; a picture could never be duplicated. Yet he was immediately excited by the weird results. Perspective was so steep it created an entirely new feeling of picture space.

His series was started in 1945 with the discovery of a camera that would give him ‘an altered perspective and a less conventional image’ that would help him to see ‘like a mouse, a fish or a fly’.

Over the next 16 years Bill Brandt completed his nudes which he considers the climax of his creative photography and the most satisfying work he has tackled. His mahogany reject, found in a second-hand shop in Covent Garden, helped him ‘to get rid of the accepted image and to view his subjects without the Cellophane-wrapping of conventional sight’. Brandt’s nudes have excited such artists as Braque, Picasso, Jean Arp, Henry Moore, as well as millions of discerning photographers and visually alert people everywhere. Bill Brandt’s later nudes, taken on the sea-shores of the Mediterranean, became increasingly abstract and gave way to natural objects until toes, fingers, elbows really are synonymous with sculptured rocks, cliffs.

Until 1960 nearly all his work had been in black-and-white, but since then he has been keen on colour landscapes, several of which have been published in Shadow of Light. He does not like colour portraits-‘the results are always too soft, they lack impact. But I do think colour can improve a landscape, particularly when the colours are odd and ‘incorrect”. Colour is so much better when the hues are non-realistic.’

Cameras

Most of his current work is taken with a Hasselblad camera although he used a Rolleiflex for many of his early works, and still carries one with him on some assignments. These cameras are invariably loaded with a 400 ASA film (‘There is no need to mention the manufacturer, is there? It sounds so much like advertising, and there is little to choose between the different makes’). He never uses a 35 mm miniature camera. ‘I have tried several models but I find the viewfinder image far too small. I like to see a larger image in order to compose my picture. Composition is essential; good design is inseparable from a good picture. Unfortunately, very few young photographers seem to have any thought or sense of design. They just snap.’ How do you cultivate a design-sense? ‘Keep looking at good pictures and paintings in museums and exhibitions. I found this of great value in my first years of photography.’

I asked him if he felt he could have created better pictures during the 30’s and 40’s with the aid of more sophisticated, modern equipment. On the whole he thought not, although he said he would have liked a good wide-angle lens before the war. This would definitely have increased the impact of some of his working-class interiors. He does not use or like electronic flash. ‘It’s too metallic, harsh.’

Working practice

All his negatives are printed on to 8 x 10in, single-weight glossy paper, unglazed, usually trimmed to leave a narrow white border around the picture area. Not very fashionable. But Bill Brandt is beyond the influence of fashion. The bulk of his prints are on grade 4 extra hard paper, which accounts for the preponderance of rich, detailless blacks in most of his pictures. This is another point that is striking about a Brandt print the areas of shadow are solid shapes, essential areas of the picture design, and not merely the inevitable result of directional lighting.

Also unlike most of his professional colleagues, Bill Brandt does not feel the necessity for constant interchange of ideas with fellow photographers. He still keeps in occasional touch with Brassai, who has now given up photography and is concentrating on writing.

Bill Brandt enjoys darkroom work and likes to experiment, printing the same shot in several different ways. ‘It takes a long time to produce a good print.’ No mass production. A Bill Brandt print is an original-seen, exposed, processed, printed and finished with utmost care to create a unique atmosphere. ‘I consider it essential that the photographer should do his own printing and enlarging. The final effect of the finished print depends so much on these operations. And only the photographer himself knows the effect he wants. He should know by instinct, grounded in experience, what subjects are enhanced by hard or soft, light or dark treatment. But … no amount of toying with shades of print or with printing papers will transform a commonplace photograph into anything other than a commonplace photograph … It is part of the photographer’s job to see more intensely than most people do.’

He has had a one-man show of his pictures in Paris, and at George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, which has a number of his prints in its permanent collection. The Museum of Modern Art, New York is planning a major retrospective exhibition for 1969. He is constantly receiving orders for prints from the Museum for sale to collectors at $50-60 each.

Books

Six books of pictures by Bill Brandt have been published; the first five are out of print and rapidly becoming collectors’ items. The first was the English at Home (1936), then came A Night in London (1938) followed by Camera in London (1948) and Literary Britain (1951), After a ten-year gap, Perspective in Nudes (1961) surprised and shook the world of photography. A revolution had been fought and won in the field of the photographic nude, and only a few close friends knew that the battle was on. Shadow of Light (1966-The Bodley Head, 63s.) a collection of Bill Brandt’s best pictures taken over the years from 1941.

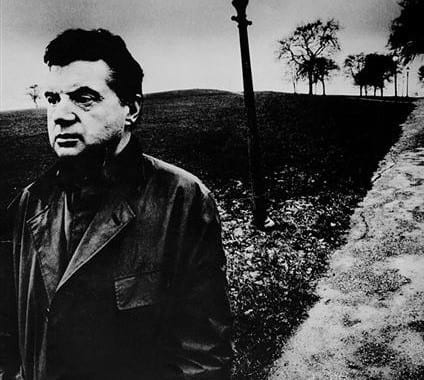

It never ceases to amaze me that Bill Brandt is a successful professional photographer. The only factor in his favour is his enormous talent. But as any struggling freelance will affirm, talent by itself is useless. Today’s success-story relies heavily on presentation, self-publicity, the right contacts, business acumen and a brash salesman approach. ‘Surprised and amused’ by the lavish praise heaped on his head, Bill Brandt is the opposite of the brash salesman. He is reflective, reticent with an attitude more suited to a don or priest than to a photographer. There has never been any question of his compromising to commercialism. His art is spotless yet successful-which is some measure of the height and depth of that talent.

He certainly doesn’t work on the principle, if you shoot enough film you are sure to get a winner. ‘I hardly ever take photographs except on an assignment. It is not that I do not get pleasure from the actual taking of photographs, but rather that the necessity of fulfilling a contract-the sheer having to do a job-supplies an incentive, without which the taking of photographs just for fun seems to leave the fun rather flat.’

‘I find that on an average I get three usable prints out of every spool … By temperament I am not unduly excitable and certainly not trigger-happy. I think twice before I shoot and very often do not shoot at all. By professional standards I do not waste a lot of film; but by the standards of many of my colleagues I probably miss quite a few of my opportunities. Still, the things I am after are not in a hurry as a rule.’

Also unlike most of his professional colleagues, Bill Brandt does not feel the necessity for constant interchange of ideas with fellow photographers. He still keeps in occasional touch with Brassai, who has now given up photography and is concentrating on writing. He feels that Cartier-Bresson’s best work was also completed in the 1930’s and his latest pictures are repetitions. ‘When you have done everything inside you, you cannot carry on unless you repeat yourself, and that’s not very interesting.’

A true loner

Bill Brandt has found it no inconvenience to work alone; it has been a positive advantage, he claims. Just as well. One of the penalties of being so far ahead of his time, leading where others follow, seeing new unexplored visions, is that you have to travel alone. In the introduction to Perspective of Nudes, Chapman Mortimer writes: ‘Brandt’s tenacity has raised the status of his art to the level of other arts. He has persisted, always alone, and he is still alone. He has never been moved by “ideas”, by novelty or suspect logic or by the bizarre. Before the difficulties of his medium, and the dangers, he has been patient, serious, loyal to his own unique images.’

Bill Brandt has also been unusually versatile -architecture, ‘candids’ of people, landscapes, nudes, rocks, portraits of the famous. How does the photographer find the field in which he should work? As usual, his own words clarify his beliefs with precision:

‘I did not always know just what it was I wanted to photograph. I believe it is important for a photographer to discover this, for unless he finds what it is that excites him, what it is that calls forth at once an emotional response, he is unlikely to achieve his best work… instinct itself should be a strong enough force to carve its own channel.

Too much self-examination, or self-consciousness about it or about one’s aims and purposes may in the early stages be a hindrance rather than a help. To discover what it is that quickens his interest and emotional response is particularly difficult for the photographer today because advances in technical equipment have made it possible to take such a wide variety of subjects under such varying conditions that the choice before him has become immense in its scope. The good photographer will produce a competent picture every time whatever his subject. But only when his subject makes an immediate and direct appeal to his own interests will he produce work of distinction.’ Cyril Connolly has said, ‘the closing of the shutter is a death-sentence, a guillotining of the moment. It is best left in the hands of a man at peace with himself’.

EXPLORE ALL BILL BRANDT ON ASX

(All rights reserved. Images @ the Estate of Bill Brandt.)