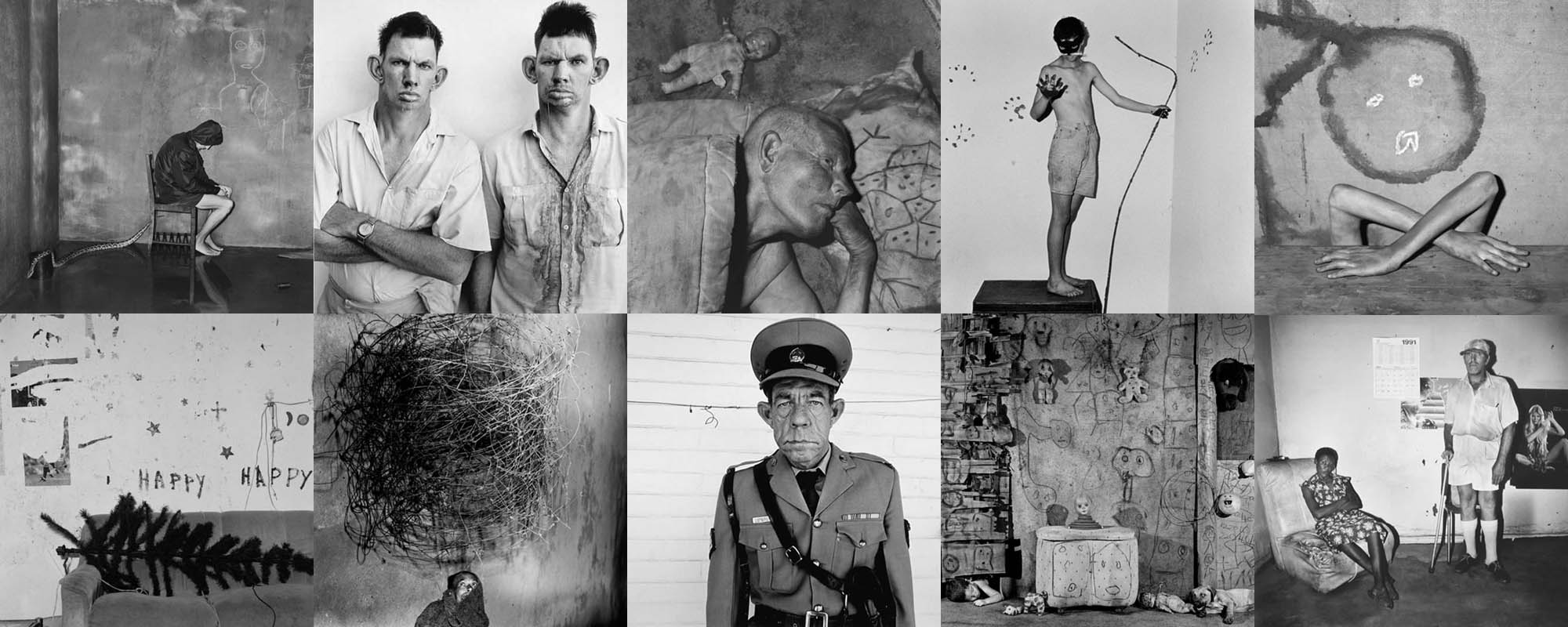

Ballen’s pictures bring to life in a variety of ways what (Man) Ray illuminated: the impulse to externalise the chaos of the mind and emotions, and the possibility that the creative process may just as soon yield a monster as an object of beauty.

By Bronwyn Law-Viljoen, Art / South Africa, 2005

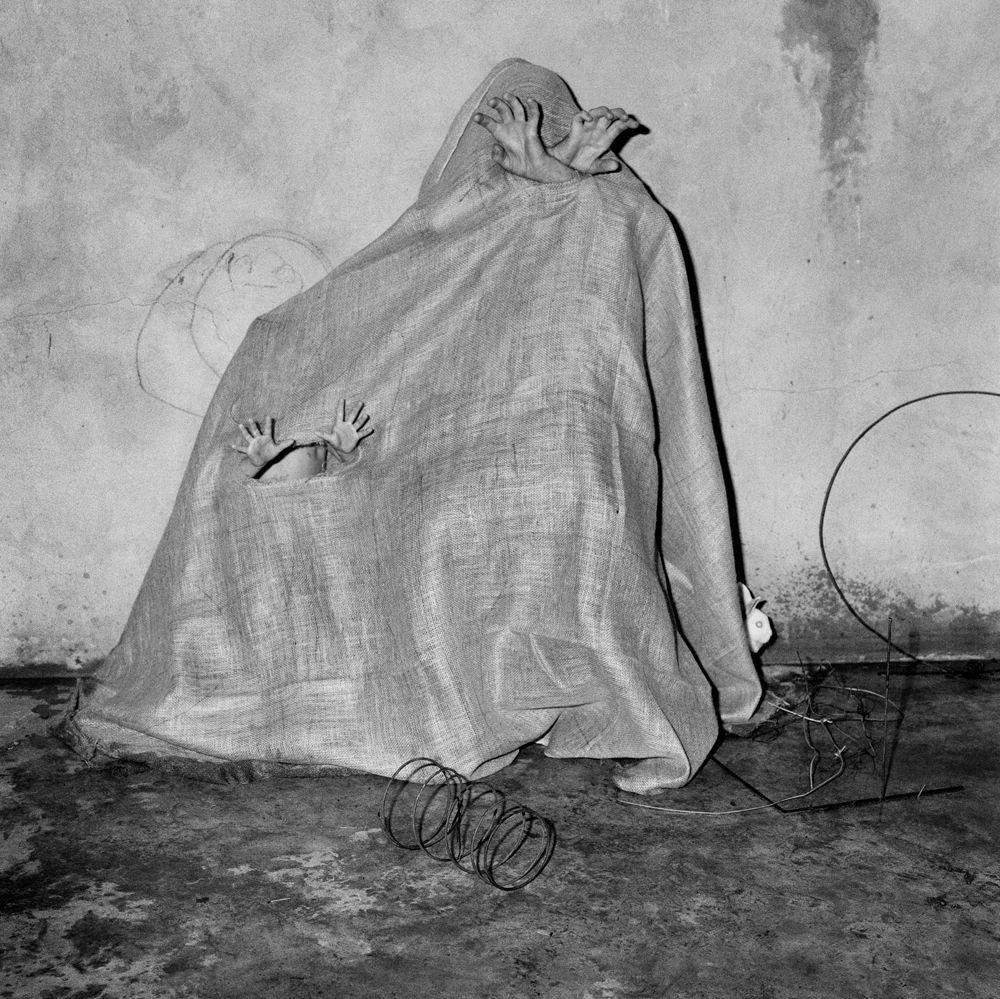

Certain of Roger Ballen’s recent photographs remind me of Man Ray’s picture of Jean Cocteau making a self-portrait out of wire. In the picture Cocteau is hunched over the sculpture, teasing out of it the shape of his own head, while on the wall behind him Ray’s lighting creates a theatrical shadow of the artist and his wire head, merged and looming like a Frankenstein over the man intent on his task.

Ballen’s pictures bring to life in a variety of ways what Ray illuminated: the impulse to externalise the chaos of the mind and emotions, and the possibility that the creative process may just as soon yield a monster as an object of beauty. Ballen understands, as Ray did, the potential in photography to transcend the boundaries between artistic disciplines, to be at once theatrical, painterly, and sculptural, without, however, losing sight of the way photography sees and creates the world. But more than this, Ballen’s work represents a logical end point to something that Ray’s photograph saw and foresaw, as neither painting nor sculpture could in quite the same way.

Cocteau’s semi-realist wire sculpture is doubly transformed in Ray’s image. In the first instance, the very mechanisms of photography – the lighting, the choice of camera angle, lens, and time exposure – create the shadow on the wall in which artist and object become an amorphous, conjoined shape, an abstraction of two objects. But another kind of transformation takes place in the space of looking opened up by the camera. In this space we are allowed to see the photographer watching the artist at work, seeing what he does not see, and even venturing an interpretation of the work.

By the time we arrive at Roger Ballen’s images, the artist-in-the-work has been shown, by Western art, not to be dead in the way that the structuralists and post-structuralists asserted but rather disseminated throughout the work as a fragmented presence (in what some have asserted is a recapitulation of Romanticism). Where Cocteau saw the possibility of self-representation and Ray embarked upon an ironic investigation of this assumption, Ballen recognises a kind of scattered, extended dream of the artistic self. His aesthetic instinct is to confront and contain the entropy of this dream.

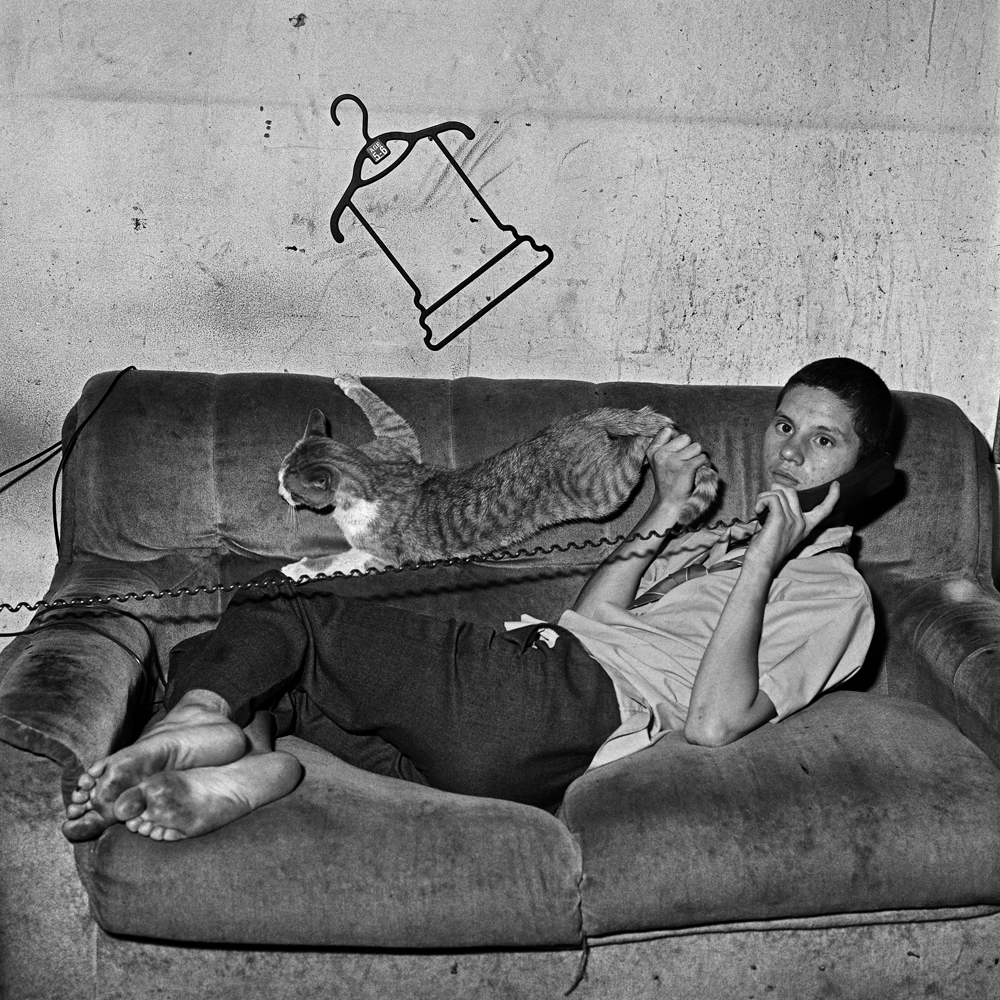

I am helped in my allusion to Ray and Cocteau by the ubiquity of wire in Ballen’s work. His sculptures are mostly abstract, and some, like Twirling Wires (2001), give a kind of knotted and cyclonic shape to the inner life. If Ballen had stopped there, however, his images would be too solipsistic to be of lasting interest.

Instead, his latest body of work seeks ways to channel a personal drama outward, to find not only an aesthetic foothold but also a place in the common consciousness. For all the power of Twirling Wires as a single image, when we pair it with others we are forced to re-evaluate its first claims on our attention. In Swirling (2003), the human subject is replaced with a flat, one-armed wooden figure endowed with crudely drawn breasts.

Three concentric circles on the figure’s torso are visually echoed in a pared down barbed-wire sculpture above its head. Next to the figure is a large spanner, the opening of which would fit neatly where the figure’s arm should be. The visual pun of arm and spanner elicits both amusement and the faint horror often associated with any implied mechanisation of the human. In Configuration (2003) the human subject is missing altogether, replaced by a ragged teddy bear.

The wire sculpture is still there, this time made of bent coat hangers and fixed to the wall with black electrician’s tape. Taken together, these images suggest the contours of a psychological landscape but, more than this, the crude machinery of wires and tools, coupled with bits of domestic detritus, creates a dense parody of modern life, as though the fragments of that life, the bits and pieces that make up family, community, the body politic, become, when broken, dilapidated, or torn from their context, the elements of a nightmare.

Ballen’s work has never fitted comfortably into categories, either historical or aesthetic.

Ballen’s work has never fitted comfortably into categories, either historical or aesthetic. Born in New York, Ballen travelled through South Africa in the early 1970s and became fascinated with the small mining towns that would be the subject of his book Dorps. He later returned to South Africa and has lived and worked here for almost thirty years, making his living as a geological consultant for mining corporations but continuing to photograph the places and people that interested him when he first came to the country.

He has had something of a combative relationship with the social documentary that has dominated South African photography of the last several decades, but though he owes much to the documentary tradition he has rejected reductive interpretations of his work, and has ventured a critique, albeit indirect, of a medium burdened with the responsibility – real or imagined – of truth-telling.

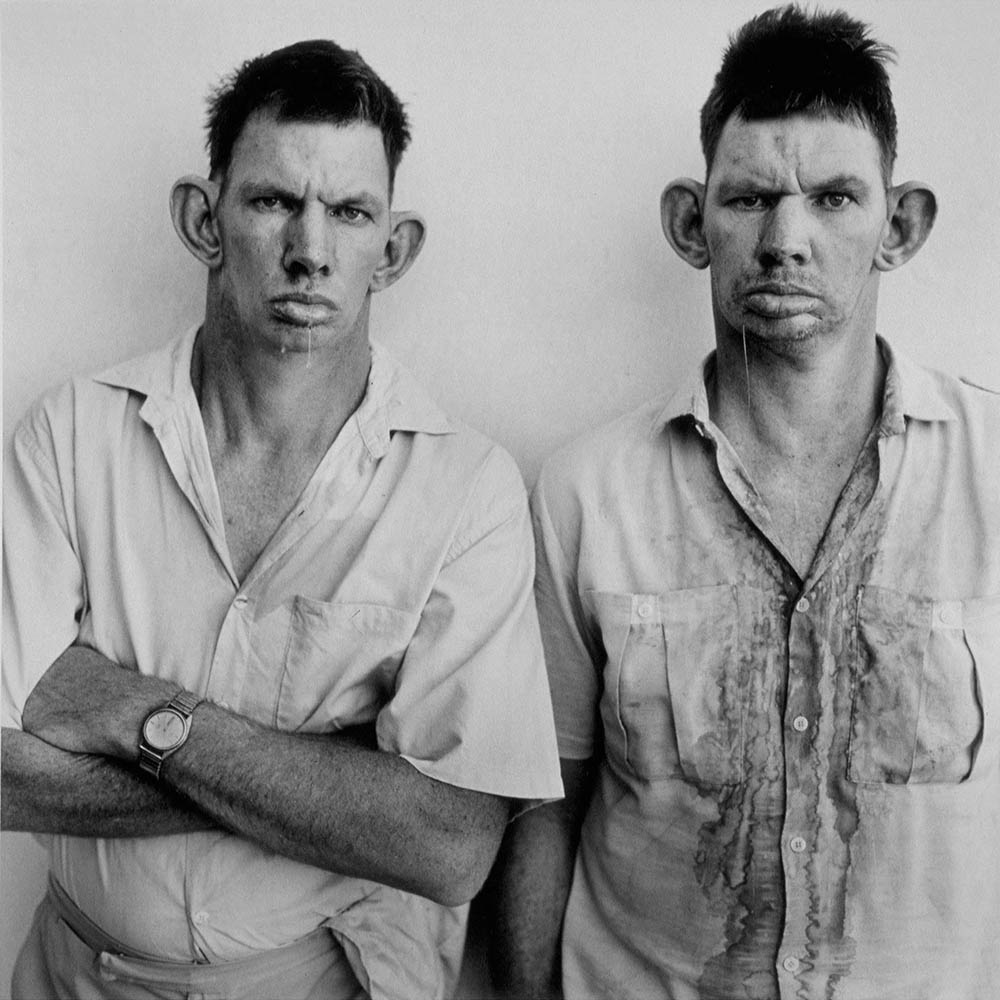

We need hardly recapitulate the debates sparked by Dorps and Platteland, except to say that even some of Ballen’s staunchest defenders missed the point when they offered, as validation of his work, his lasting relationships with his odd-looking subjects. This defence assumes that Ballen’s photographs should tell us the truth about people’s lives, that social documentary necessarily privileges truth over fiction, and that as a photographer working in South Africa Ballen is compelled to adhere, at the very least, to a liberal humanist interpretation of the world.

Whether or not Ballen is a liberal humanist I shall not attempt to discover, but what does seem clear is that he can no longer be mistaken for a social documentarian. The evolution of Ballen’s work lies less in the conceptual impetus of the photographs as in a tightening and consolidating of their formal language.

Though he still alludes to elements of social documentary – the focus on outsiders, the preference for black and white, the unblinking dead-pan of the visual vocabulary – Ballen’s approach to the photographic event is now more explicitly that of a painter contemplating a canvas or a sculptor arranging and shaping objects.

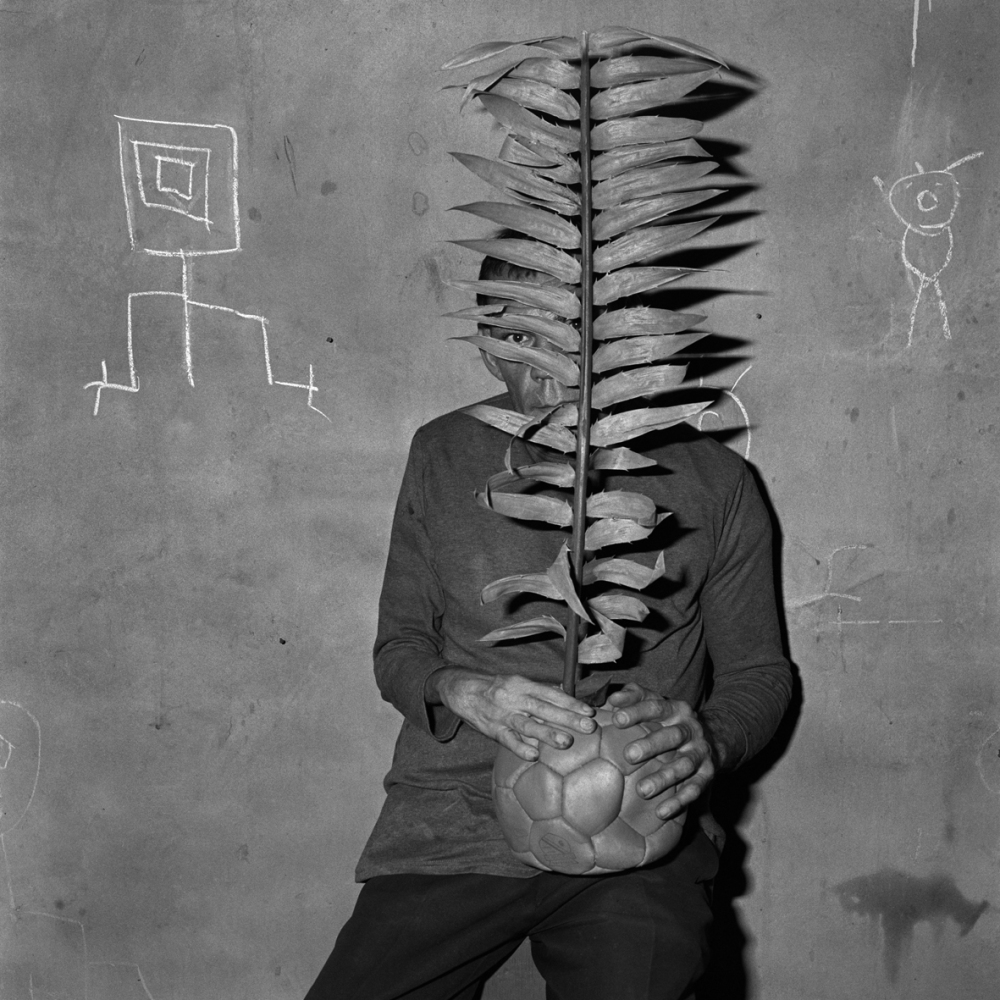

Some of his drawings, paintings, and masks point to Ballen’s interest in ’art brut, a term formulated by the French painter Jean Dubuffet to describe what later came to be known as “Outsider Art.” Dubuffet had, through the 1930s and 1940s, become interested in the art of children, the insane, and criminals, and he asserted that such people had a connection to the imagination unmediated by the tendency, in most sane (and presumably non-criminal) adults, to rationalise or inhibit the tumultuous world of the subconscious.

In one sense, Dubuffet was describing what had long been underway in European art: the absorption of the ‘exotic’ or ‘naive’ into painting and sculpture. In hindsight the results of this (in artists from Picasso to the Surrealists) are more interesting than the now-problematic theories about so-called primitive art.

In Ballen’s work, crude, childlike drawings and masks are part of a dense symbolic universe rooted at once in the subconscious and in an apprehension of the decay, isolation, and absurdity of life in the world into which, as Heidegger expressed it, the individual is thrown.

While Ballen creates sculptural or painterly effects, however, he is alive to the ways in which photography transforms those effects on two fronts. On the one hand, the medium allows him to dematerialise concrete things and, through the use of hard, direct lighting, to flatten perspective until it seems that objects and people are pinned to the grimy walls against which he composes.

On the other hand he is able to trade on the assumption – still deeply rooted despite decades of photographic experimentation and illusionism – that photography reflects or captures the empirical facts of the real world. Ballen’s images unsettle most when this assumption encounters the strange objects, weird characters, bleak settings, and animals of his visual repertoire. Ballen has worked almost exclusively in square-format for the last decade, a self-imposed discipline that works upon the photographer in the same way that the fourteen lines of a sonnet do upon a poet.

The square-format photograph, like the sonnet, is most successful when it is able to maintain and manage the tension between formal restraint and conceptual freedom.

The square-format photograph, like the sonnet, is most successful when it is able to maintain and manage the tension between formal restraint and conceptual freedom. It announces itself as much through its shape as its content and when it works, it conveys meaning inside structure without ever being heavy-handed. Ballen often takes advantage of the visual symmetry of the square, as in Untitled (2003).

Here a round tin plate containing a lizard and a goldfish is anchored firmly in the centre of the image. But he is not afraid to break this symmetry and place objects off-kilter, as in Under the Moon (2000) in which a bulb hanging left of centre is balanced by the weight of the prone figure at the bottom of the frame.

The square compels him to pay careful attention to detail since he cannot rely on the eye moving across the visual plane, taking in one element at a time. It is perilous terrain and Ballen does not always escape the pitfalls (an occasionally distracting smudge leading the eye off the image, a tipped horizon where a level one would be stronger) but when he hits his mark, he achieves images of enormous emotional and formal power.

The formal discipline, even conservatism, of these images, however, is deliberately set at odds with their subject matter and mood. Ballen’s black comedy, though it often breaks the tension of his tableaux vivantes, produces a deep unease – we don’t know, looking at some of his pictures, whether we should laugh. At the same time, Ballen’s iconoclastic comedy derives some of its force from its references to kitsch.

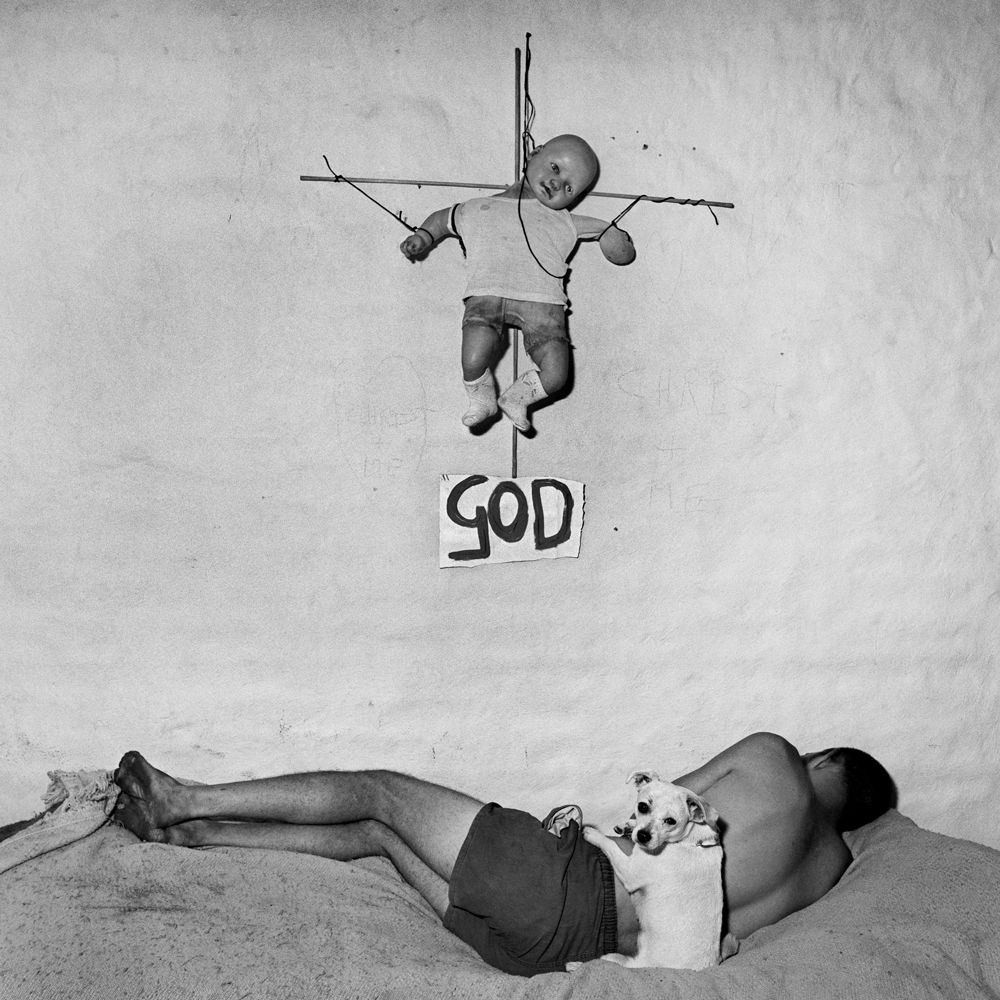

In Loner (2001), for example, a crudely fashioned crucifix hangs against a wall, the Christ figure replaced by one of those disturbingly lifelike baby dolls. A sign underneath the cross reads “God” in large letters. Beneath this effigy, a shirtless boy with blackened feet lies with his face to the wall and behind him a white dog gazes wistfully into the camera.

The image engages in a visual parsing of the elements of kitsch – the religious iconology, the small animal, the plastic doll – until what emerges in its stead is a delightfully blasphemous joke, but undercut by the pathos of the dog’s gaze. Sentimentality, kitsch’s evil twin, is the ever-present danger in photographs of animals but Ballen avoids it through a complete lack of romanticism in his perception of the relationships between humans and animals.

Loner, 2001

In Loner the dog’s gaze is counterbalanced by the unsettling fact of that prone human figure facing away from the camera. Ballen’s animals seem to occupy two fields of reference: in some images they are hapless victims of human mischief while in others they are granted symbolic status. In his 1977 essay ‘Why Look at Animals?’ John Berger remarks, “no animal confirms man, either positively or negatively… its lack of common language, its silence, guarantees its distance, its distinctness, its exclusion from and of man”. Perhaps the greatest challenge of looking at Ballen’s recent work is in encountering his awareness of this exclusion.

Human beings and animals coexist, in Ballen’s experience of the world, in an unfriendly relationship. If any connection exists it becomes apparent only, Ballen seems to suggest, in death. In The Chamber of the Enigma (2003) a figure with a mask-like, plastic face lies on a bed, covered by a blanket, while a brindled puppy stands on a cloth-covered table to the right, playing the role of the psychopomp conveying the body of the dead to the next world.

If we were looking for a Barthesian punctum in this photograph, a point of recognition and strangeness, it would have to be that white table cloth that manages to tip the image, literally and figuratively, over to one side: it is both a shroud and a symbol of bourgeois gentility, utterly out of place but bizarrely appropriate.

Ballen has described the world of his photographs as “an amalgam of the asylum, the subconscious, and the Castle,” which is to say a territory that begins in the dark corners of the mind and extends to those terrifying institutions of human society described in different ways by Kafka and Foucault, institutions created to incarcerate, scrutinise, display, and rehabilitate ourselves and our fellow creatures.

But Ballen’s theatre of the dregs also sifts through the particulars of our places of habitation, the sometimes-marvellous junk of human domesticity that is at once emptied of meaning and heavy with loss. His images frequently convey a large-hearted mischief and sense of the comic, but they also turn inwards to paranoia, riddles, and secret jokes. It is Ballen’s willingness to contemplate all of this terrain that makes his images so compelling.

The strength of photography lies not in its ability to show us real places and events, but rather, as Ballen observes, in persuading us that the places it purports to have seen really exist. We assign painting to the realm of make-believe, but continue to give photography the benefit of the doubt, which is precisely the quality that appeals to Ballen. We should not, however, think of Ballen as cynical; he too believes in the world of his own photographs. It is, after all, he says “some sort of place”.

In Ballen’s work, crude, childlike drawings and masks are part of a dense symbolic universe rooted at once in the subconscious and in an apprehension of the decay, isolation, and absurdity of life

Sentimentality, kitsch’s evil twin, is the ever-present danger in photographs of animals but Ballen avoids it through a complete lack of romanticism.

Bronwyn Law-Viljoen is a critic and books editor based in Johannesburg

http://www.artsouthafrica.com/

ASX CHANNEL: Roger Ballen

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

(© Bronwyn Law-Viljoen, 2005. All rights reserved. All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher)