Bert with Guitar, 1992

Shelby Lee Adams was recently interviewed by an entity that decided not to run the complete text. We are bringing it here to ASX.

Q: I’ve read that you spent much of your childhood in Kentucky, but that mountain people weren’t held with much regard in your family. Can you tell us about the experience that changed your thinking?

Shelby: I’ve never changed my thinking I’ve always loved my grandparents, family and especially the mountain people I came from. I grew up in a holler called Johnson’s Fork, where my grandparents and family owned land, were born, lived and died, complicated and educated families with opposing views. My difference is unlike others perhaps; I also simultaneously grew up traveling up and down the eastern seaboard attending different schools during my parents’ work time. Seeing and experiencing other important worlds, but always returning to Johnson’s Fork and attending part of the same school year at the Hot Spot Elementary School.

The Holler Dwellers I photograph say I’m a messenger to the outside world showing life as it really is. Some town people say I’m an insider by being born there but that I’m one who has betrayed his people. My heart and soul is in this place and I photograph the people and places I care about. My father’s family history: My grandpa and grandma Adams had seven sons and two daughters in their family. They grew up through the depression era. Three of my uncle’s benefited by receiving college educations; two became doctor’s, the other a superintendent of schools in Indiana, a major accomplishment for a family, especially then. My father and his three remaining brothers worked with grandpa Adams to support the rest of the family. Grandpa Adams was a timber man, who made and sold mining timber to the coal companies and he was a farmer, the farm and his timber business needed laborers. That’s the way families managed back then. There was family sibling rivalries and jealousy; times were hard, resentments between family members spilled over into class and cultural evaluations. My father and his brother Doc Adams were divided in their opinions on their own diverse culture, as it is still today within many Appalachia families. That division within, I have worked hard to understand and reconcile within myself and with my people. I became a part time companion during my high school days of my uncle “Doc Adams.” He taught me mountain ways, served as my mentor of sorts, we traveled the hollers together, mountain people loved him and we shared this incredible life, the best of times. It was then I first saw and experienced the hard life some still live today.

The Hog Killing, 1990

Q: What do you hope people will get from your photos?

Shelby: “My work has been an artist search for a deeper understanding of my heritage and myself, using photography as a medium and the Appalachian people as collaborators with their own desires to communicate. I hope, too, that viewers will see in these photographs something of the abiding strength and resourcefulness and dignity of the mountain people.”

Shelby Lee Adams, published in first book “Appalachian Portraits”, 1993

“In spite of the fact that I no longer live in that world you bring to life in your work, I connect with it very strongly. It sustains me and instructs how I look at the world. Seeing that world through your eyes gave me something I never fully grasped before, and I’m not even sure if I can explain it to you. It gives me a kind of pride in the hardships we all survived. Pride in the goodness of those people — my people.”

Sarah, [A viewer of work] From Mississippi, May 2010

“I think as long as you can be with somebody, it helps them; talkin’ and takin’ pictures, is your way. When I used to go to restaurants, I’d feel ashamed. I felt like people could look inside of me and see something wrong. Now, I feel free of that. You’ve helped my family with that too.”

Sophie Childers, Summer 2007, whose family has been friends and photography subjects since 1976.

Q: Of all the photographs you’ve made, which ones stay with you emotionally?

Shelby: With some families I am now photographing their fourth generation. With that alone comes a great deal of satisfaction because you feel connected and accepted as family. My relationships are authentic, deep and evolving. I have particular photographs I’m more emotionally charged by than others, but prefer to keep that personal. I work with and identify with parts of all my subjects, empathizing with their situations. Sometimes it takes years of visits and time to really understand some people’s circumstances, but the emotional acceptance is usually always immediate. My subjects and friends always ask me to come back; that is emotionally rewarding. Emotional excitement exists for me in the physical home visits reconnecting and with the plans for future possibilities of meeting new families and people that will welcome me to continue my work.

Mary on Bed, 1990

Q: Some people say that your photos are too composed, that they portray a romanticized or antiquated view of the culture. How do you respond?

Shelby: I grew up in Eastern Kentucky in the 1960’s and 70’s during the height of “The War on Poverty” days. As a high school student, I was asked to show some professional photographers from outside around to meet families I knew. Their magazine stories when published offended us, they didn’t show us what they were actually photographing and certainly never told us what they intended to say. We all felt betrayed, especially me; I provided the introductions. Was the media there to help or use us? As a teenager I grew up studying art, very suspicious of photography.

When in art school my photo teacher recommended I try a 4×5 view camera in Kentucky. You have to work with a big camera on a tripod and formally pose your subjects. Everyone sees and knows where the camera is. Making 4×5 inch Polaroids shows everyone clearly what is going to be in the photos and that most always elicits a positive response from your subjects. The completed composition is what the subjects see in the Polaroid first, before you make the final photograph.

This manner of working has always seemed more honest to me, especially in this culture. I say my work is collaborative because my subjects respond to the Polaroids and we change or contribute to the compositions their ideas, appearances, locations and feelings. I think it’s a more honest exchange, with no surprises – I’ve been working in this manner since 1974. A formal way of working, yes but we have this history of betrayal and misrepresentation by the media and mountain people respond comfortably seeing ahead what is being photographed. I practice this same procedure when a book project or a story is being edited, everyone sees, hears and has input on the entire story or book dummy before publication. We don’t shy away from or ignore our media history, but try and rectify. I learn from my people because of this kind of engagement.

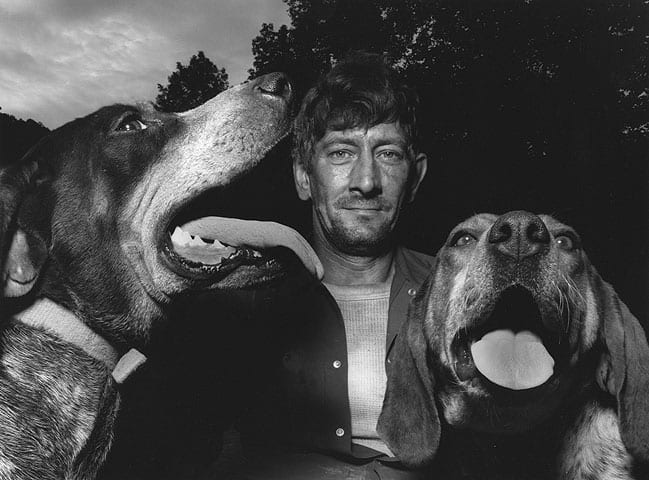

Chester with Hounds, 1992

Romanticizing, my dictionary defines a romantic as someone who is concerned more with feeling and emotion than form and intellectual qualities. I photograph a feeling and emotional culture and my subjects like this look, their look, and my work could not have continued for now 36 years otherwise. Perhaps we are a romantic culture in the hollers and less defined. Lots of great romantic music comes from this country and the larger world embraces it. Concepts and ideas contribute to making enduring art. It is part of my focus to capture and create images of the more tolerant accepting humanity here, balanced with authenticity, not someone else’s ideals. Still all art and photography are subjective and the viewer can deny or accept its relevance, to my mind that makes it more powerful. Your acceptance or denial engages you, you become a participant, like it or not.

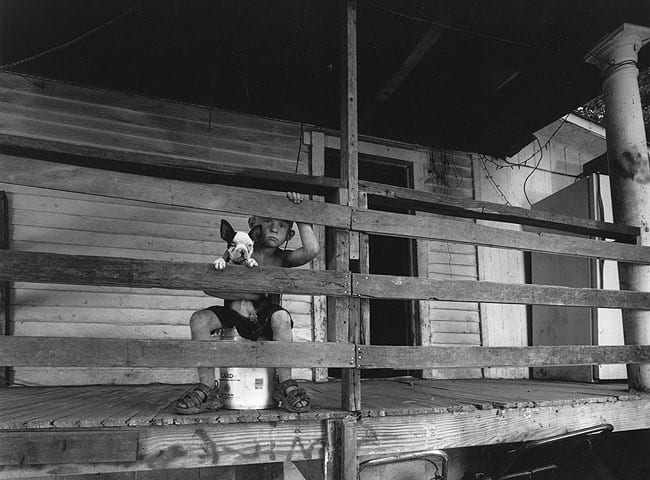

Regarding antiquated, which means old-fashioned or out of date. One could ask my subjects; they feel much as I do, that were preserving and expressing something very important, a complex and seamless view, a family based culture openly demonstrating and reflecting many of its “affects” and behaviors, from generations, a way of rural life that is continually transforming openly. For me, a portrait is a timeless metaphor representing the present while reflecting upon fragments and glimpses of past generations, of how our people have been treated, how they have adapted, overcoming despair and surviving. For the contemporary viewer, here is a culture that openly accepts itself without shame, yet we shame them for our discomfort, creating caricatures. When mainstream society continues to isolate and deny many of its own problems, veiled in hypocrisy. We can learn much here if we desire to connect with these rural lives strengthening ourselves with compassion.

I view my work as personal, documenting my culture as an insider with my own stylized vision, with passion and genuine relationships, not assignment work as sometimes gets misinterpreted. My portraits I hope will continue their own evolution, recognized as enduring, all encompassing and observing a revered life style to those participating. Still many people today continue to impose their values and judgments here, under the guise of, “for the good of the people.” Instead of acceptance and working with the true local people equally and mutually, they wish to reform. Some Appalachians and others deny our holler peoples’ primal cultural origins because they feel less if acknowledging and idealize something grander for themselves; this attitude continues contributing to the low cultural self-esteem and identity problems. The essence of a human being is here maybe more so, as in all nations and all lands.

Tyler & Sheba, 2001

Q: While the folks in Kentucky are your primary subjects, you’ve done other work as well. If you could photograph anyone from the Appalachian South, who would it be and why?

Shelby: I have pretty much always photographed where and with whom I was personally interested you see there has to be a personal connection to making good portraits. In the beginning of my career I photographed for magazines and corporations, but that funded my livelihood and how I made a living. Later, I worked as a college professor teaching photography. Now I teach photo workshops on the national level. I have found traveling and photographing internationally to be a great stimulation to keeping my Appalachian work thriving. I have photographed in Mexico, Bogotá, Columbia, Egypt, Israel, Great Britain, Greece, Spain, Portugal and Scotland, to name a few places. I hope to visit and photograph in Ireland soon. But, doing all of that, I felt very much a tourist, which is why I have never shown or published this work. In retrospect, going back to the Kentucky holler’s has always been the most fulfilling and purposeful, my “calling” you could say. My credo has become expressing the need for mutual equality within “All of Us”. My grandma Bertha from my mother’s family, we called her Berthie’ who slowly went blind as I grew up taught me that we are all spiritually equal, no matter what our positions. In the spiritual world there is no top or bottom of the class. We must all strive and learn to overcome ourselves, accepting each other, living together no matter how different, without prejudice and judgments.

Shelby Lee Adams has received a Guggenheim Photography Fellowship for 2010-11.

http://shelby-lee-adams.blogspot.com/

ASX CHANNEL: Shelby Lee Adams

(© Shelby Lee Adams, 2010. All rights reserved. All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher)