In the 1960s he began to neglect his appearance. He didn’t cut his hair or trim his beard and he wore a ragged black suit.

Miroslav Tichý: Tarzan Retired

By Roman Buxbaum

“O làsce šeptal tichý mech” (Of love murmured the quiet moss)

Karel Hynek Màcha, Màj (1836)

When I was a little boy, my grandmother used to say: “Wash your hands! Otherwise you’ll be like Mirek Tichý!” For my grandmother, Tichý was a prime example of what not to be. In the town between the hills and the vineyards of south Moravia he was the representative “Different Man”, embodying the revolting and the ridiculous. For me, he was always a powerful magnet. I was never afraid of this tall, burly, long-haired man with a full beard and torn black clothes. I never felt disgusted by his appearance.

When I was about five or six, Tichý made a pinhole camera for me out of a shoebox. In the bathroom, we pasted a piece of photographic paper on to the back of the box. In the lid on the front we made a hole with a pin and stuck a piece of tape over it. Then we set out for the city. One photograph we made together with the shoebox has been saved: in the small picture you can see the Renaissance tower of the town, in front of which is an old Škoda car. (Behind them is where the old Jewish ghetto used to be, before it was torn down in the late 1960s.) That was not only the beginning of my admiration for Miroslav Tichý, but also the first step on my own road as an artist.

First, I was his neighbor. And then, I was his pupil, the man who documented him, a collector of his work, and above all his admirer. None of that, however, qualifies me to write an article for a book about Tichý. I lack the professional qualifications that one needs to write an art-history essay. I also lack the requisite objectivity. Perhaps the reader will forgive me if I provide a bare-bones report occasionally supplemented with pictures and recollections of this extraordinary man.

Miroslav Tichý was born in Netcice, a small village in Moravia, on November 20, 1926. He was the only son of the tailor Antonìn Tichý and Žofie Adamcovà of Netcice, the daughter of the mayor of the village council (who had fourteen other children as well). When Miroslav was four years old, his father bought a house in Svatoborskà Ulice in the nearby town of Kyjov, and opened a tailor’s shop there. That’s how he became our neighbor for many years. The corner house of the Tichýs’ had two large shop windows, which let daylight into the shop. The family lived in the smaller rooms of the house and helped to run the business, which, when times were good, employed not only Tichý’s father employed but several other people as well. To this day when the front door of the house is opened the old bells of the former shop rings to announce the arrival of a visitor.

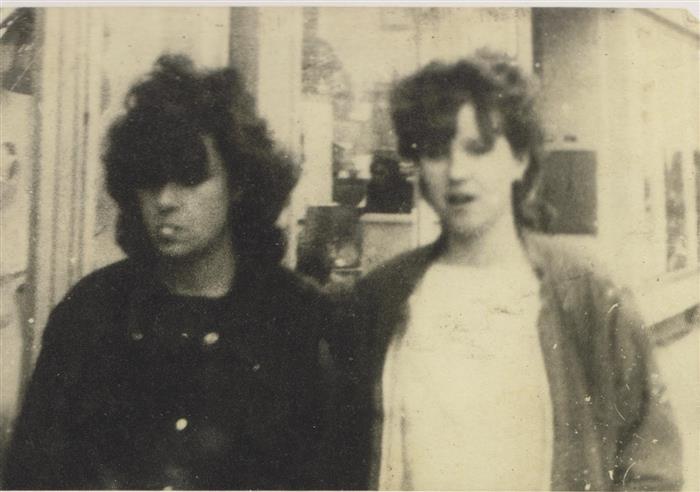

Tichý was an introverted, bright child and, owing to a gift for languages, he excelled in school. While attending the state secondary school he befriended my uncle, Harry Buxbaum. They shared an interest in art and politics, and went on bike trips together to the main town of the district. Just after the war both men studied in Prague and regularly met in cafés. In one photograph from those days they are happily walking along the boulevards of Prague. The world seemed to be all right again. Those were times of hope, a short respite between two dictatorships. In the years 1945-46 Tichý completed his foundation year at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, where he then went on to study for two years with Professor Jàn Želibský. In that studio, Tichý was considered a good draftsman and was popular with his fellow students, owing to his sense of humor. He still enjoys relating stories from those days, from an episode of life unspoiled by anything.

After the Communist takeover in February 1948 drastic changes took place at the Academy. Respected professors and assistant professors were quickly thrown out. Instead of drawing women models, the students were forced to draw workers in overalls. Tichý refused to draw them. It seems that the political crisis overlapped with a personal crisis, and the young artist succumbed to both. He stopped working and spent his time walking about Stromovka park in Prague, and avoided his friends. He quit the Academy and had to do his compulsory military service. I often wonder what his life would have been like if the Communists had not taken power. Would Tichý have remained at the Academy or would he have left for Paris? Would he then have ever discovered photography? We shall never know. But, as Harald Szeemann said when he first looked through Tichý’s originals, “Intensity will always find its medium.”

The 1950s in Czechoslovakia was the ice age of Stalinism. The country was gripped by the paranoia of espionage. With its purges, the system dealt not only with all the democrats but also with any one who had a different view, with competition in its own ranks, and also with groups on the periphery of society. In those days fraught with danger and uncertainty an important change probably took place in Tichý’s psyche.

Between 1957 and 1959 he was repeatedly treated in the Opava psychiatric clinic, which, fortunately was run nearby where Harry Buxbaum was working as psychiatrist and could look after his friend Miroslav. I found several letters from those days, which Tichý had written to his parents, and also the correspondence between his mother and Buxbaum. The correspondence refers to the horrors of a psychiatry that was closely linked to the repressive machinery of the totalitarian regime. In the second half of the 1950s the Khrushchev years began – the first signs of the Thaw. Tichý returned to his native Kyjov, and lived at his parents in isolation on money from a modest disability benefit. He drew and painted only for himself, remaining true to his own style, which was reminiscent of prewar Modern art. In 1958 he made a total exception and participated in a group exhibition of young artists in Brno.

He was, however, strong and combative. “I’m like a samurai,” he said, “my sole aim is to destroy my enemies.”

In the 1960s he began to neglect his appearance. He didn’t cut his hair or trim his beard and he wore a ragged black suit. If he tore his trousers, he patched them up while he still had them on, using a piece of string or wire. He liked to work as little as possible. In summer he used to lie on the roof of his house and sun bathe. He was the opposite of the ideal new Socialist man, that is, the clean-shaven, muscular foreman who tried hard to exceed the Five-Year Plan. In the eyes of his shaken fellow citizens Tichý was an oddball and a loser. He was, however, strong and combative. “I’m like a samurai,” he said, “my sole aim is to destroy my enemies.” At that time too Tichý’s spirit was unbroken, and he didn’t take any abuse. I found a report about his arrest by the local police, which provides evidence of police brutality and also sheds light on the role of the State psychiatrist that worked with them.

In the second half of the 1960s there was a second political thaw, which culminated in the Prague Spring. But the acts of repression against Tichý did not let up. The brutality let up, but not the continuity. Before every May Day and other Communist holidays a car would stop in front of the Tichýs’ house, and two middle-aged policemen in undersized green uniforms would get out. The bells above the door of the former shop began to tinkle. Mrs. Tichý, already prepared, would wait with a packed little suitcase and try to get her son to agree not to make a scene. The policemen also tried kindly to persuade him, assuring him that he would be home again in two days. The regional secretary of the Communist Party was supposed to take part in the celebrations, which is why they had been given orders to detain all dissidents and to take Tichý to the clinic in Kromž. There, they would, as always, “normalize” him, which meant they would wash him, dress him in the new clothes that his mother had packed in the little suitcase, and then let him be. “Good-bye, till we come again before the celebrations of the Great October Socialist Revolution,” they’d say. That is more or less how they used to detain Tichý and try to “normalize” him. In the course of twenty years, paralyzing despair gripped most of society. Tichý did not let himself be normalized.

I clearly remember Tichý’s daily visits to my grandmother Bożena, with whom as a child in the 1960s I always used to spend the summer holidays. Tichý came into the kitchen – the place of social life in every Moravian home – and sat down on a crate of coal beside the stove – because of his dirty clothing he humbly sat only on the wooden coal bin. My grandmother kept on working, either at the stove or walking back and forth across the kitchen. Tichý was given something to eat and drink, and then they became engrossed in long discussions. I didn’t understand the topics, but I recall that they were about politics, the arts, and books.

In the 1950s and ’60s Tichý used to associate with several local artists: Vladimir Vayek from nearby Svatoboice, Vladimìr Vìũek, enk Stak, and my grandfather Old ich Herman, who taught him how to paint. At that time Tichý rented an attic room from my grandmother and set up a studio there. For us little boys that room in the equally fascinating attic had an irresistible attraction. Through the keyhole appeared fragments of a mysterious world: we saw oil paintings, a pile of drawings, and large puppets carved out of wood. A magical world was exhibited before our eyes.

Soon afterwards, my grandmother’s property was nationalized. She became a tenant in her own home. My great-grandfather’s rooms in the former saddlery began to be used by the Obnova cooperative, which repaired leather goods. Tichý was given an eviction notice; the cooperative demanded that he clear out of his studio. But Tichý refused to be evicted. The correspondence between Tichý, the cooperative, the local National Committee and the District Court, to which he turned with his case, provides evidence of the atmosphere of repression in the 1970s. The lone fighter Tichý stood his ground, but, for “economic-political, social, and also security reasons” they threatened him with forced eviction. When, despite all that, he still refused to give in, the State bureaucracy once and for all lost patience: on 27 March 1972 Tichý’s pictures were thrown out onto the street. It seems that the loss of the studio traumatized him so he stopped drawing and painting. In previous years he had also experienced a crisis in which he put aside his pencils and brushes, but being evicted from his studio this time meant turning away from traditional painting and drawing. Even back in the 1960s he used to carry around a camera and had begun taking photographs. Now the streets of Kyjov became his studio.

The mess in Tichy’s home immediately engulfs every visitor. Mountains and valleys of books, pictures, tools, unwashed dishes, drawings, and paper cover the floor, table, and all the furniture.

After the Soviet occupation, which began in late August 1968, my father and Harry Buxbaum escaped with their families to Switzerland. Not until 1981 was I able now as a Swiss citizen to visit my grandmother and Tichý again. Tichý, however, no longer wanted any studio; he no longer drew or painted. People ask me, What are you, Mr. Tichý? Are you a painter, a sculptor, or a writer? I reply: Do you know who I am? I am Tarzan in retirement. From the beginning of the 1980s I used to visit Tichý regularly, and for a long time I was the only one he showed and gave his photographs to. We looked through them together. Tichý leafed through them and gave me this one or that one, depending on what I liked. He never accepted money; I could contribute to his basic needs only secretly. I need about a crown a day to live on, he would say. I looked at him skeptically and gave him the food that I brought. Tichý would turn round and open a cage made of two wire hand-baskets from a supermarket, which he had tied together with wire: I am not eating. For days I haven’t eaten. I have two potatoes and half a kilogram of flour here. Rats or mice eat all my food. They leave me just scraps. That will last me a whole week. I offered him a sausage. I don’t eat animals! An animal, in my opinion, is like me. It has a head, a heart, legs. And, I might add, we are not even as good as animals, because a human being has only two legs, and an animal has four! We laughed, and clinked our glasses of rum. People kill these super-beings to eat, but they would really deserve a decent burial will full honors. Jana, Tichy’s neighbor, has been looking after him every day since his mother died. She’s afraid of the mice in his home. She told him that she was setting mousetraps, but Tichy’s feelings were hurt: The mice are my kin. If you kill them, you kill me! I want to be buried beside them!

The mess in Tichy’s home immediately engulfs every visitor. Mountains and valleys of books, pictures, tools, unwashed dishes, drawings, and paper cover the floor, table, and all the furniture. The electrical wiring hangs free in the air. True, we see two washbasins and one tap that works, but a bucket has stood under the basin for years now, and the water flows into it. I use one bucket of water a day.

When visiting him, as soon as you overcomes the initial shock and grow a bit accustomed to the unmistakable stench, his place begins to feel cozy. You sit on a shaky chair and drink from a brown mug, which once upon at time used to be white. Like the walls of the room, the books, and the photographs, the mugs too are allowed to go the way of all things from birth to death. I am a prophet of decay and a pioneer of chaos, because only from chaos does something new emerge. Tichý, however, moves in all directions of his turf masterfully and confidently. Disorder seems to be his agenda, not because of laziness or an inability to tidy up. Rather, it is his intention. When the visitor has finished looking through some book or at a photograph and returns it to Tichý, he or she will probably hear: Throw it on the ground! Other laws apply here. The world of chance and chaos constitutes a ferment in which material matures, immersed in the depths of Tichy’s ocean, to be brought back to the surface, but changed and worn by time.

Tichý is a reactionary in the truest sense of the word. While Yuri Gagarin was conquering outer space, Tichý was making cameras out of wood. He put himself into reverse, moving backwards against the ideology of progress. A genuine reactionary, and a very effective one, because unlike the Five-Year Plans he achieved his aims. The Stone-Age photographer was the embodiment of an insult to the small-town Communist elite. He became the living antithesis of progressive thought, of the Marxist theory of history moving in a straight line.

Tichý may have abandoned the usual social conventions, but he did not become an autistic loner. Unlike the thinking of the masses, he backed the individual: he has lived only for himself. He went into internal exile and became an observer on the margins of society. He befriended the local dissidents and was, like them, kept under surveillance and arrested. The police once forgot to pick me up on May Day. I already had my little suitcase packed and was waiting for them to come and take me to the insane asylum. I waited and waited, but they didn’t come. I then got tired of waiting, left the house, and went out on to the square. There were red flags everywhere, women in traditional folk costume, Pioneers were marching four abreast in the street. At the town hall they had built a rostrum, and on the podium someone was making a speech. I went to the church on the other side of the square, climbed the stairs, and sat down on the top step. I was then at the same height as the rostrum and could see everything. And everyone saw me. About two minutes past by and suddenly my policemen were standing beside me. And I was soon on the way to the insane asylum.

Of course they also tried to put Tichý behind bars by the legal route. They would have loved to have locked him up for some sexual offense; after all, he was always photographing women. But there was nothing he could be accused of; no harassment, no soliciting in that sense he was clearly beyond reproach. During one trial at the Brno court, they therefore ordered, evidently in desperation, a sixty-page expert’s report on hygiene. The report was presented to the court in four copies and had to be read in full during the trial. During the trial Tichý referred to the mechanism of oppression as a piece of theatre of the absurd. The expert witness had concluded his report with the following offense: Tichy’s clothes were with certainty discovered to have contained two lice and a cockroach. When the judge asked him what he had to say to the accusation, Tichý replied: Summon them as witnesses!

Tichy’s first solo exhibition, at the Seville Biennial (BIACS), was opened by Harald Szeemann in the summer of 2004. It was followed in 2005 by a large retrospective in the Kunsthaus, Zurich. His hitherto almost unknown work was now being exhibited almost all over the world. Tichý, however, did not attend the exhibitions. He doesn’t like exhibitions, particularly not in Europe, which he considers degenerate and doomed.

The paintings and drawings from his years at art school, as well as later works, are mainly portraits and figures, rarely landscapes or still lifes. He painted and drew what he saw almost always from Nature. In the 1950s and 60s he drew and painted (in watercolors and oils) people around him, particularly women (including some preserved portraits of my mother, aunt, and other women neighbors). But he also works from memory, many people today are fascinated by his ability to recall the features of a woman he has only glimpsed on the street, and then to depict her in several quick strokes. There are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of pen-and-ink and charcoal drawings, whole female figures or torsos. Reclining, standing, walking, they are always the same motifs we encounter later in his photographs. Tichy has remained faithful not only to the motif, woman’s body, but also to the style of pre-war Modern art, which he came to know at the Academy in Prague, in books, and in periodicals about art. It was mainly Neo-Classical works of Picasso and Matisse, which influenced Tichy’s early art. His academic work comprises between 100 and 200 oil paintings and a vast number of drawings Tichý destroyed an unknown number of works.

Making things himself was a demonstration of his independence. He foreswore the conveniences of the modern world so he wouldn’t have to accept the demands that world made on him.

In the 1970s and 80s the style of his drawings slowly changed. The lightness and elegance of the line, which often recalls fashion design, vanish. His line gradually became hectic, applied with blows in rapid staccato. Dark shades of green and brown took the place of the radiant colors of his early works. What remained was, again, the same motif, but the women’s figures no longer seem so sweet; they have gradually been distorted and are sometimes almost lasciviously caricatured. In this period Tichý discovered new methods, painting on wooden panels, which he found in the courtyard, and print-making. For his prints he was able to use anything with a smooth surface: pieces of wood, linoleum, a chopping board, a piece of Plexiglas, a piece of cellophane, bits of a plastic pail. After scratching out the drawing he applied paint with the palm of his hand and then, applying pressure with a spoon, transferred it to paper. He made a considerable number of these monotypes. Only rarely did he use the technique of engraving in aluminum. Most of the paintings, drawings, and prints are still owned by Tichý, scattered chaotically about his home. Many of them are soiled and damaged because they are among the household objects used everyday. The hall of the house is barricaded with paintings and frames, which lean against the walls. Others are piled up high, because their artist treats them very unkindly when they get in his way, he mercilessly throws them aside. Many of them exhibit damage done many years ago. Cracks and dents are the most frequent injuries. Nevertheless, there is a clandestine order to the chaos, and Tichý usually knows exactly where to look for a certain painting.

The oil paintings are covered with such a thick layer of dust that they cannot be recognized. If a visitor wants to look at some painting, Tichý wipes it off with a wet sponge. Beneath his fingertips briefly emerges a picture in dark, richly glowing colors. But the dust stays on the surface of the painting. As I wipe it, the dust becomes transparent, Tichý explains. He painted his last pictures in the 1970s. They are canvases of large dimensions, painted in many layers with symbolic subject matter. The form slowly deviates from the models used while an art student, and the spatial composition goes beyond art-school conventions. The paintings describe dramatic experiences, conflagrations, death.

One of the paintings shows two female figures. It is a small oil Tichý painted after a theater performance he saw in Brno. On the right is worldly love, Eros. On the left is heavenly love, Agape. The dancer in the middle of the picture has to choose between the two. I painted a little door for him in the picture, here on the background between the two figures. This door leads to the void, to nothingness, to the light…

Ever since Tichý lost his studio, he has had to work in the very modest conditions of his home. In isolation and under the pressure of external obstacles it was difficult to paint from live models. Women did not come to his place, so he had to go to women. When asked why he became increasingly involved with photography, he replied: The paintings were already painted, the drawings drawn. What was I supposed to do? I looked for new media. With the help of photography I saw everything in a new light. It was new world.

The only thing I know for sure about the beginning of Tichy’s work in photography is that the first camera he began to use sometime in the 1960s was an old field camera inherited from his father. The photos are without numbers and without dates. The way they were stored has meant they have been shuffled again and again like playing cards. Approximate dating is possible only by judging from the styles of clothes, kinds of cars, and other things in the photos. The materials on the reverse side of the mounting and the frames also reflect the times when Tichý used them. Most of the photographs were made in the 1970s and 80s. I had a planned number I wanted to do: I would make such and such a number a day, such and such a number in five years, and when I did it, I quit. He bought his film, photographic paper, and chemicals from a drugstore next to the church. To save money, he often bought 60-mm film and then in the darkroom cut it lengthwise into two strips. He set up a darkroom on the courtyard of his house. He made himself an enlarger from boards and two slats, which he pulled out of the fence. The slats are joined together with sheet metal so that they can be slid in and out lengthwise, that’s how he focuses the picture. To keep the enlarger head from slipping, he wedged a piece of sheet metal between the slats. Obrzek He made the lamp box by placing a light bulb into a tin can. He took a lens from a disused camera. Between the light source and the lens he made the negative tray out of plywood with a hole for rewinding the spool of the negatives. The whole enlarger was hermetically sealed with black paper, tape, and shreds of fabric.

On principal Tichy refused equipment that was offered to him. Making things himself was a demonstration of his independence. He foreswore the conveniences of the modern world so he wouldn’t have to accept the demands that world made on him. That’s fine. It’s good enough, he repeated. When he needed black, he went to the chimney for a handful of soot, which he then mixed with oil. When his feet were cold, he warmed them in the ashes. Frugality, the reduction to essentials, and self-sufficiency are part of the personal philosophy that has accompanied him throughout his life. Remaining unwashed and wearing ragged clothes was a liberation from the standards set by a society that had aims different from his.

Sometimes he pressed the camera to his chest and aimed the camera at his subject by turning his whole body halfway round.

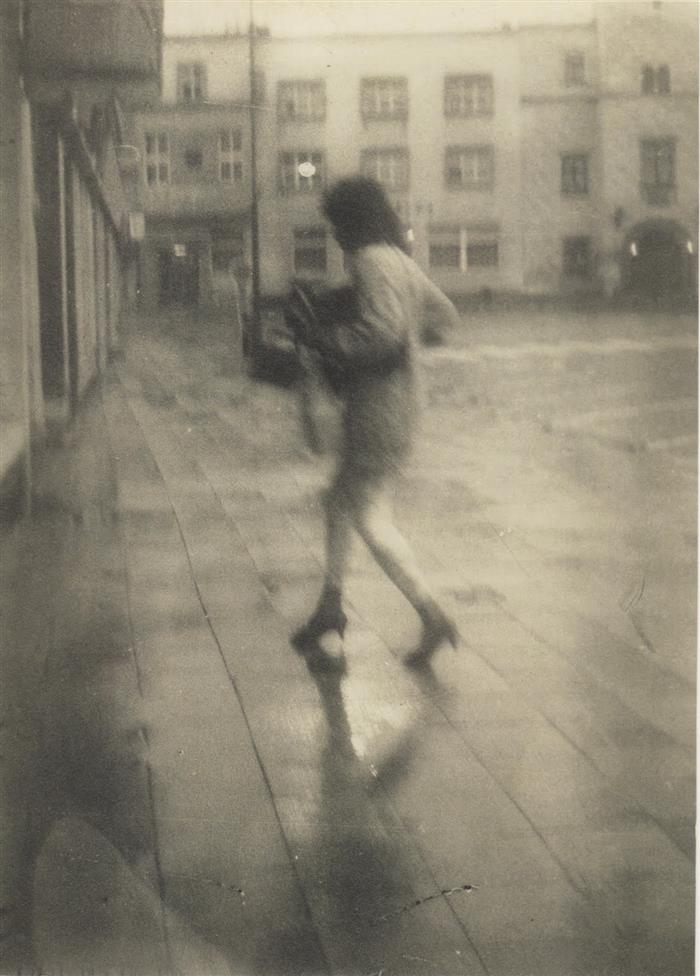

Tichý carried a camera under his sweater. Usually it was the cheapest Bakelite camera, made in the Soviet Union, which he had bought in a junk shop and adapted to his needs. (For example, he fitted it with another lens and improved the rewinding of the film spool.) He carried the camera and case on a string around his neck. He let it hang down on his right side, so that it wouldn’t be seen. As soon as something attracted his attention, he reached over and with his left hand raised the hem of his sweater, and with his right hand opened the camera case and pressed the shutter release, without even looking in the viewfinder. Sometimes he pressed the camera to his chest and aimed the camera at his subject by turning his whole body halfway round. The movement was so fluid and fast, that it was almost impossible to notice it. In this way, he says, laughing, he could hit a swallow in flight.

Tichy’s day began early. Usually he was already outside by six o’clock in the morning. When I asked him how he planned his photography and found his subject matter, he said: I never did anything but pass the time. Because I had set out for the town and had to do something there, I took snapshots. I didn’t determine anything. The time I spent on my walk determined what I would photograph. Everything is determined by the world spinning round. You can’t live longer than the number of times the world spins round. That is a given, and it’s called, for example, Fate. That is how he made a record of a day spent in an imaginary city of women.

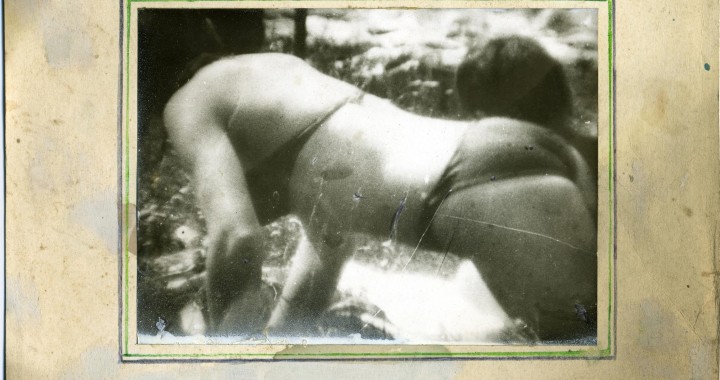

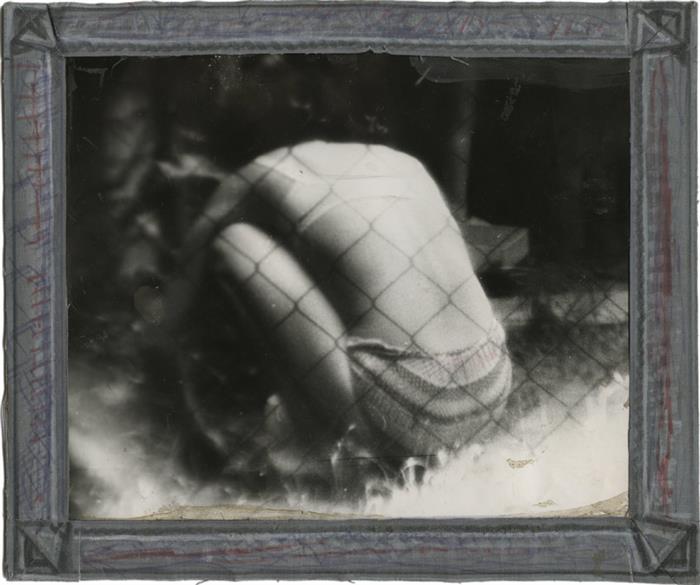

He had his favorite places where he regularly went to take photographs: bus stations, the main square by the church, the park opposite the secondary school next to the swimming pool. Although Tichý was not permitted to go to the pool, he could photograph undisturbed from the park through the wire fence that so often appears in his photographs. Here he found the models that he had lost when life-drawing with nude models was banned at the Academy. He photographed wherever possible. Some shots are of women who are smiling at him, talking with him, posing, joking, or are, by contrast, arguing with him because he is taking photographs of them without their permission. In essence, however, Tichý kept a distance from his models. He photographed quickly, imperceptibly, or from quite far away. I am a mere observer, the most painstaking observer possible. Not of human beings! Of everything! Later, he was more specific about what interested him: Everything, even innards, every atom! I have to explore every atom, because I am an atomist, he says laughing. I asked him about his attitude towards women and the erotic. A woman, for me, is a motif. Nothing else interests me. I didn’t run wild with women. Even when I see a woman I like, and maybe I could have tried to make contact, I realize that that I’m not actually interested. Instead, I pick up a pencil and draw her. The erotic is just a dream anyway. The world is only an illusion, our illusion. Tichý is suspicious of his motives and his feelings, and continues to abstain. I see shapes and convert them into mathematics. It is a composition of elements. The whole world consists of numbers. Someone tell me what the largest number is! And what is the smallest? And it is only in those infinite billions of elements that something can be composed. That happens by itself, beyond me. After all, I simply don’t exist in fact. I am a mere instrument, an instrument of knowledge, or something. Everyone says life, life, but no one knows what life is. Do you know what life is? Define it! When I once asked whether he would enjoy it if we organized an exhibition for him in Prague, he replied: Enjoyment is a concept that I absolutely disallow. How could such a skeptic enjoy something! Momentary feelings! I don’t take anything seriously anymore. Least of all myself.

Tichý has photographed people in the park and on the balconies of the tower blocks all around. That requires a powerful telescopic lens with a focal length of between 300 and 500 mm. He made one himself out of materials he found lying around. He made a system of lenses out of old eyeglasses and Plexiglas. The way he works almost brings to mind the Stone Age, but he wouldn’t have managed without an intimate knowledge of the laws of optics. As Tichý relates: With a knife I cut a lens out of Plexiglas and then I sand it with sandpaper. When I asked him in amazement whether it worked, he replied: Of course it worked. When I do something, it has to be precise. Of course it worked imprecisely. That was perhaps the art, he added, laughing. Then I grind the lens with various sandpapers: first, course sandpaper, then finer and finer, until you can see through it beautifully. And then what? It needs to be polished. That isn’t a problem: you take toothpaste, mix it with cigarette ash, and then you polish it. And that’s what I photographed with.

The framing of the photographs mattered a lot to Tichý.

For the body of the telephoto lens he uses paper tubes or plastic drain pipes. He often put several lenses in them, which he fixed with glue or asphalt. He also focused with a children’s telescope: from a board he made a wooden holder and mounted the camera on it. The telescope was attached to the holder with dressmaker’s elastic at the appropriate distance from the camera lens, so that the picture on the film was in focus. The whole thing looks like some kind of weapon. In a similar way, he also made very complicated cameras. From cardboard and plywood he assembled the body, sealed it with asphalt from the road, and painted it black. From two empty spools of thread and dressmaker’s elastic he assembled the rewind mechanism, a sort of pulley system, to which he attached the shutter. The shutter was made of plywood with a little window cut through it. Depending on the tension of the dressmaker’s elastic the shutter flipped through the camera quickly or slowly, exposing the film for a shorter or longer period. It’s hard to believe that he could make such subtle, Impressionistic pictures with such a clumsy instrument.

Every time I visited him, Tichý always had hundreds of undeveloped rolls of film in his darkroom, hundreds of them hanging on a laundry line. The only window was blacked out with black fabric. A light bulb painted red provided the light. On a table was his homemade enlarger, and beside it was a shallow bowl with developer. A large pot for cooking was filled with fixer. A washbasin was used to rinse off the prints. He looked at his negatives first under the enlarger, then chose the shot and the crop. With scissors he cut a piece of photographic paper (or he often only tore it by hand). He then put the photo paper on the table into the light, and when he reckoned it had been exposed long enough, he took it away. He submerged the exposed paper in to the developer in the shallow bowl. He left it over night in fixer in a tub on the courtyard. He didn’t use tongs, working instead with his hands, which is why some of his photographs have a fingerprint in the upper right-hand corner (or even a whole handprint, if he forgot to let the paper go when exposing it). Once the photographs had been in the water bath long enough, he took them out, dried them on the laundry line, and pressed them in books. Lastly, he put the photos in a large box beside his bed, so that they would always be in easy reach. That completed the first phase of the printing process. Each print is unique. Very few negatives were printed more than once, and the prints of those are each considerably different in format, crop, and exposure.

I once asked Tichý what criteria he used to choose photographs for enlarging. He replied: I didn’t choose anything. I put it in the enlarger, and then moved it, and I printed whatever looked a bit similar to the world. That’s all. When I asked him what “similar to the world” meant, he replied: Everything that is, that is the world. If I could recognize something there, I printed it. He then continued working on the prints in the box. When he liked a photo, he took it out of the box, looked at it for a while, then took scissors and cut off part of it. He wasn’t too concerned about right angles, but he cared a great deal about the laws of composition. Sometimes on the back of a photograph he penciled a note about the color of the mount, for example, light ochre. Often he wrote down two or three colors. I need inspiration. Then I also see colors.

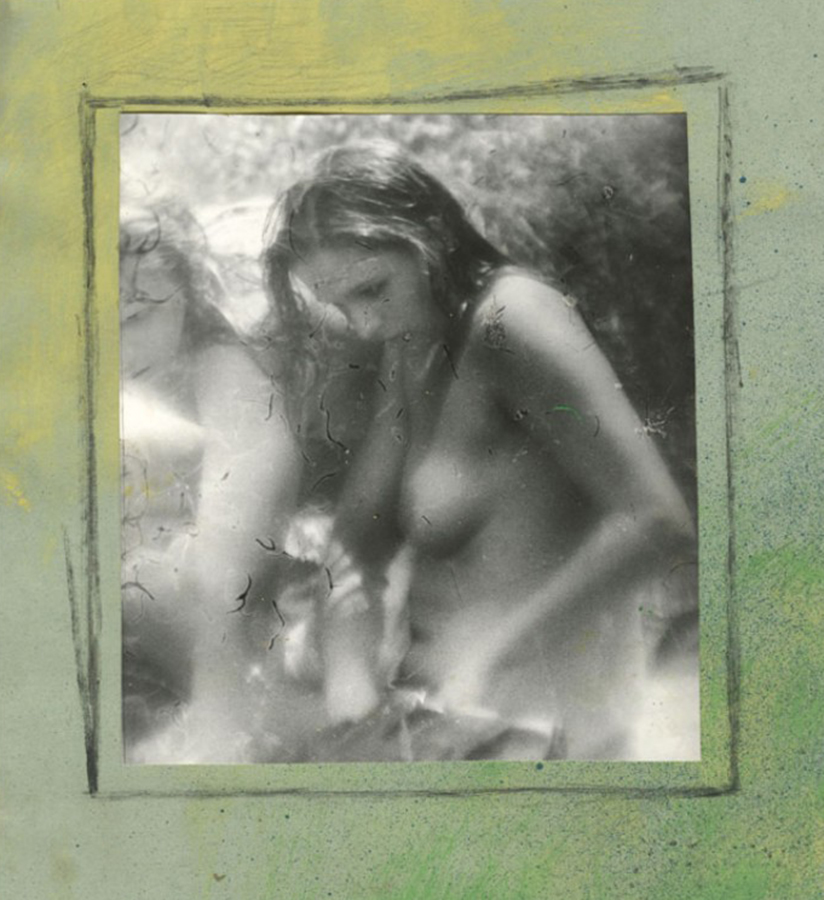

For more than forty years Tichý studied only the phenomenology of the female figure.

The framing of the photographs mattered a lot to Tichý. For two years I haven’t managed to frame a single picture, he complained. He put the photographs into passpartous that he also made himself. Out of a pile of paper he pulled a piece of paper whose color suited the photograph. Then he found a piece of cardboard and pasted the paper onto it. Professionally he pasted paper of the same weight to the back, so that the cardboard wouldn’t warp. (For this he used a page of newspaper with the TV program listings or a page out of book, a paper bag, a drawing, or even a photograph he no longer wanted. The backs of the pictures thus provide an intriguing glimpse at Tichy’s activity as a collector). Later he glued down the photograph or cut out a frame. Once a photograph was in the passpartous, he painted it with paint or colored it with colored pencils.

For more than forty years Tichý studied only the phenomenology of the female figure. That was his only motif. For Tichy the photographer, everyday small-town life changed into a day in the studio at the Academy. The poses of the models remain the same as when drawing a nude: they are reclining, standing, leaning, bending over, photographed from the front, from behind, he studies the back of the nude, the whole figure, the torso. There are some very detailed movement studies. Legs, in particular, are a topic he works on tirelessly. Art! What is art? Art is imagination, an idea. Schopenhauer: Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung. The world as will and idea/representation! An idea is a dream. When I take a photograph, I don’t think about anything. And I don’t take seriously anything that I feel or think. It’s like playing cards, a game! Movement is a central theme of his work: When you photograph, movement is the most important thing. And composition. Contrast makes the photograph. Darkness and light, that’s composition. Photography is painting with light!

He has repeatedly used pencil on his enlargements to emphasize unclear contours. Sometimes he has reworked and tinted whole parts. The transition to a drawing is fluid. I improve it a little. When I pointed out the stains from bromide, he replied: A mistake, a mistake. That’s what makes the poetry, gives it the painterly quality. Philosophy is something abstract, but photography is concrete, a perception. The eye, what you see. First of all, you have to have a bad camera! If you want to be famous, you have to do something so badly that no one else in the world does it as badly! Not so nicely, beautifully elaborate; no one is interested in that.

Tichy’s works are often on the borderline between drawing and photography, and each is unique.

It is astonishing how many mistakes and shortcomings Tichy’s works can bear: everything is underexposed or overexposed, out of focus, made from scratched negatives, developed on paper that is either cut by hand or even torn, with dust and dirt on everything, filth in the camera and in the darkroom, finger prints, bromide stains, places gnawed by rats and silverfish. The road the photographs take once they leave the darkroom is a dismal one. Their maturation begins by being thrown into a pile of dust for several years. The harsh post-production methods in Tichy’s studio are as follows: sitting on the photographs, sleeping on them, walking on them, cutting off the edges, improving the composition with a ball-point pen or colored pencils, folding them, using them under a table leg to keep the table from rocking, spilling coffee or rum on them, letting mice and silverfish feast on them, throwing them out of the window, forgetting about that, even when it begins to rain, then finding them again and saving them, sticking them onto a piece of cardboard, giving them a matt, and, finally, noting on the back the TV listings. The factor of the forbidden and the seized in the hunt for pictures corresponds to the neglectful handling of the photographic material.

Tichy’s works are often on the borderline between drawing and photography, and each is unique. In the same period as Arnulf Rainer and other artists, he developed the technique of painting over the photograph. The deliberate disdain for the photographic ideal of cleanliness is not reflected in his work as a shortcoming or brutalization, but as the intensification of sensuousness. Thanks to his rough handling of the material, the figures of women emerge from soft, Impressionistic light as if by a miracle. Their essence, their being, is not expressed in realism, in perfect depiction, but, on the contrary, in the negation of them. They present reality as illusion, as a mere semblance, beauty becomes a dream. For that, however, Tichý needs not only a bad camera, but also, indeed mainly, a different way of looking at the world and a miracle. Even the unattractive then becomes enchantingly beautiful. Imperfection creates poetry. Poor-quality lenses change the world. Scratches turn into unreal textures and a meta-base, and dust and spots from bromide are transformed into unique traces of time. To let time flow. To paint with light. Chance, says Tichý. It’s all just chance.

(According to an update note that has been posted to the official Miroslav Tichý website, Tichý has severed all ties with Roman Buxbaum and www.tichyocean.com)

Statement of Miroslav Tichy (PDF – translated into English)

ASX CHANNEL: Miroslav Tichý

For more of American Suburb X, become a fan on Facebook and follow ASX on Twitter.

For inquiries, please contact American Suburb X at: info@americansuburbx.com.

All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher