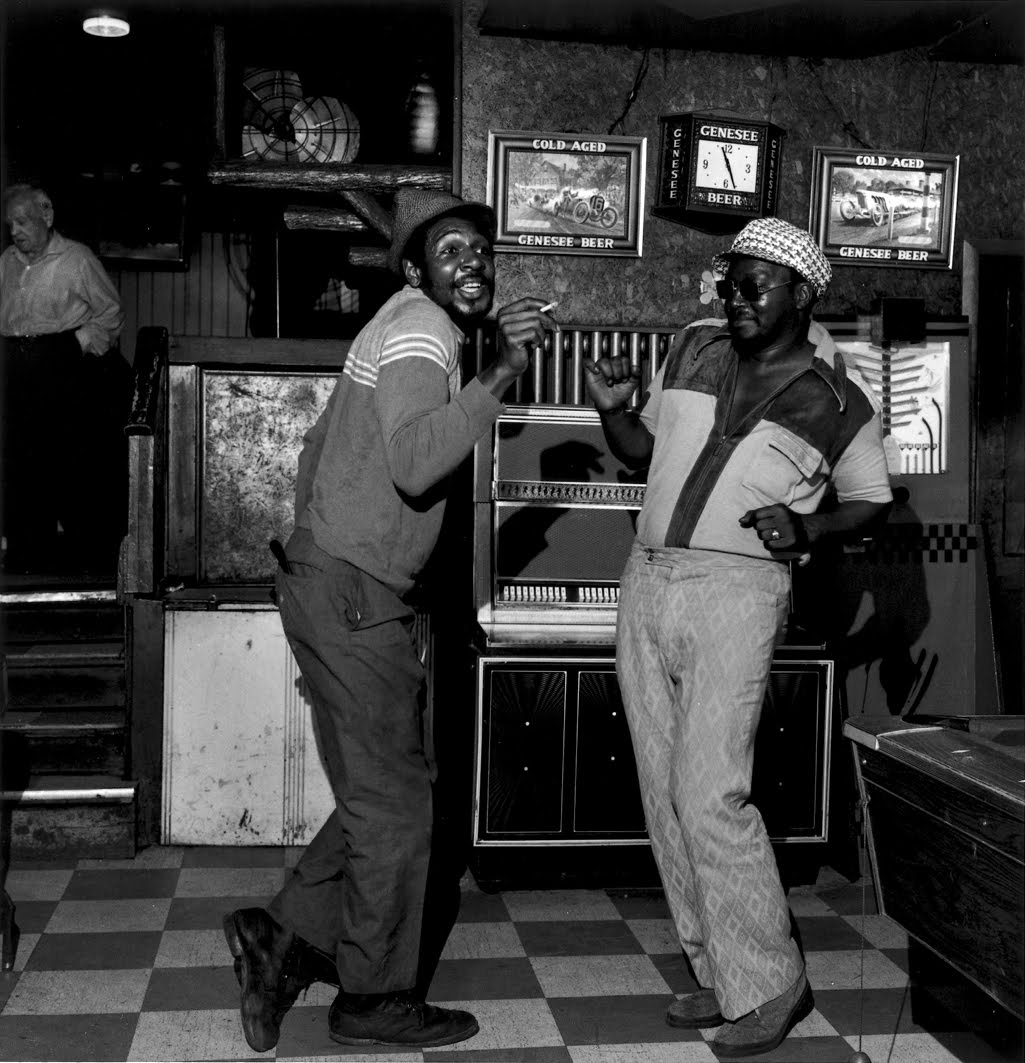

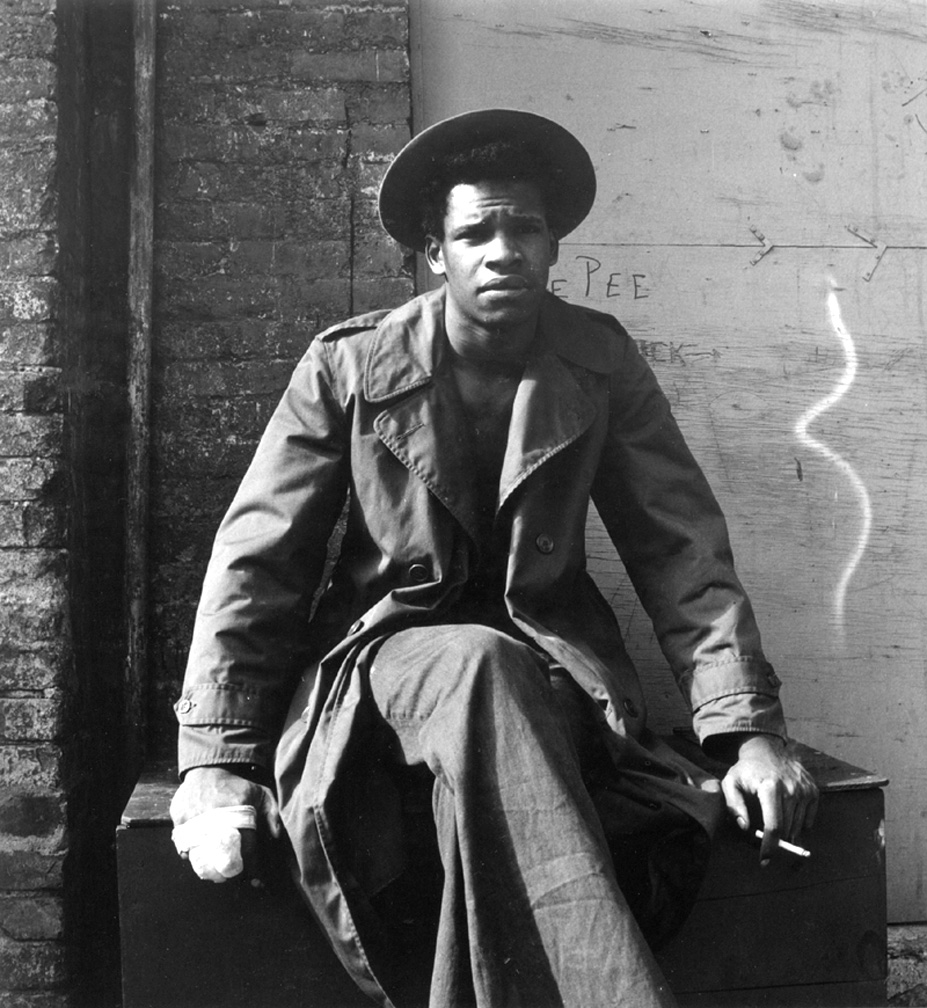

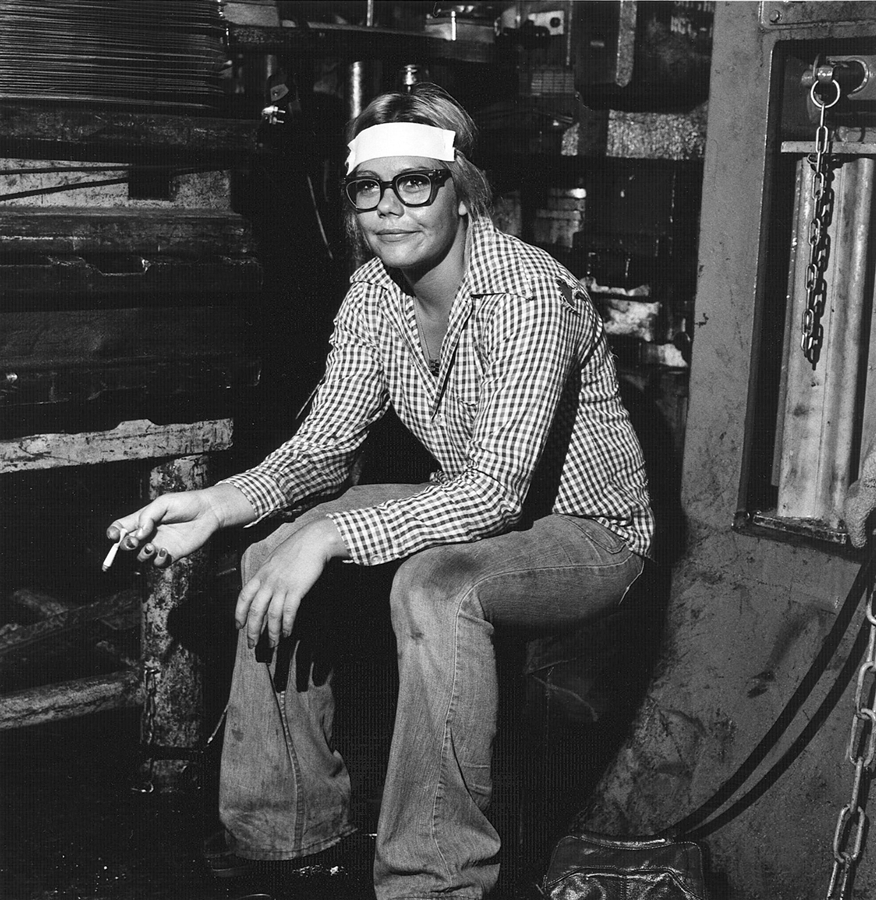

Rogovin photographed what he calls “the forgotten ones” in storefront churches, the neighborhoods of the Lower West Side and Buffalo’s East Side, and in former steel mills of Lackawanna and Buffalo.

Excerpt from The Forgotten Ones

It is like a movie set without actors. This Saturday morning in April 2008, Main Street in downtown Buffalo is all but deserted. Perhaps it comes alive when spring and summer eventually arrive in western New York, but now the street teeters between presence and absence. Light accents the architectural details and weathered tones of amber and vermillion on early twentieth-century edifices and reflects off the sleek white marble facades of banks and businesses.The eye is drawn up to the gold-domed bank, the replicas of the Statute of Liberty set 352 feet above the street on faux pyramids, and the massive, anachronistic 32-storied City Hall.

On street level, “for rent” or “for sale” signs poke out of first-floor windows of empty store fronts. Slicing through Main Street is a trolley line dotted with clean waiting areas for few passengers.There is no traffic. Perhaps some civic committee imagined Main Street as pedestrian space where people would gather. But this is not an Italian piazza or a Mexican zocalo. Human activity seems hidden within interior structures.

Mall Courtesy Rules” greet the would-be shopper and warn citizens. They cover a range of human behaviors, a litany of “NOs”: no loitering, littering, shouting, running, hanging over rails, horse play, soliciting, congregating, or sitting on floors. Near the bottom of the list are “no illegal drugs or weapons” and “no taking photographs or videos without written permission.” This is shut down and disciplined space. These same rules or a diluted version might be found in any well-lit and populated mall anywhere in America, but here they are stark because there is so little left to regulate and guard.This is begrudged space for people with little money. It does not speak for or about them.

For more than fifty years, Milton Rogovin’s photography has spoken for those who blur into the background of cityscapes. Rogovin photographed what he calls “the forgotten ones” in storefront churches, the neighborhoods of the Lower West Side and Buffalo’s East Side, and in former steel mills of Lackawanna and Buffalo. His black and white portraits of Native Americans, Yemeni families, Chileans, Appalachians miners, and other workers around the world are neither staged nor visually manipulated. Like Lewis Hine portraits, they suggest a quiet reciprocity—the Main Place Mall on Main Street is no one’s main place. Empty and gated spaces surround a handful of discount stores.What it does have in abundance are well-displayed rules and regulations. The “Ten Main Place empathetic eye of the photographer is evidenced in the subject’s self-presentation.

Milton Rogovin bears witness to the thwarted and silenced in the tradition of Lewis Hine and Tillie Olsen. Neither he nor his subjects “forget.”

Inspired by Bertolt Brecht’s “A Worker Reads History”, Rogovin composed “Working People”, a series that answers the poem’s questions about overlooked laboring humanity, Brecht’s “particulars,”who built and sustained the edifices of the powerful. Rogovin’s portraits, whether of a Chilean mother and child or a Scottish miner or a young woman in her doorway on the East Side of Buffalo, resonate not only because of his skillful eye, but also because of his capacity to evoke the inherent dignity of each person. His portraits demonstrate a mutuality between subject and photographer.

To preserve and ensure the availability of his body of work (Rogovin is now ninety-eight), Milton Rogovin’s negatives, contact sheets, and 1,300 master prints were deposited at the Library of Congress in 1999. In 2007, 20,000 pieces of correspondence were added to the collection. In the fall of 2008,Rogovin’s master collection of 3,500 photographs will be placed at the Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. Also, a recent collaborative biography by Melanie Anne Herzog, Milton Rogovin:The Making of a Social Documentary Photographer, traces Rogovin’s formation as a photographer and his distinct aesthetic.

Mark Rogovin comments on the Rogovin legacy and the desire of the family, including his sisters Ellen and Paula, to preserve and make available Milton Rogovin’s work:“My parents wanted people to ‘use’ the photographs. My sisters and I have begun to understand the value of these unique images—of poor and working people, of steel workers and miners, and we are making these photos available in a complex of ways.”

(Consult www.miltonrogovin.com for Rogovin images and resources intended for classroom and curricular development.)

To teach the city through the lives of people in their own neighborhoods, consider two of Rogovin’s books from which the portraits included in this essay are reproduced: Triptychs: Buffalo’s Lower West Side Revisited, with commentary and background by Robert Coles, Stephen Jay Gould, and Joanne Wypijewski, and Milton Rogovin:The Forgotten Ones, with Dave Isay, David Miller, and Harvey Wang. These photographs and oral histories emerge from a particular geography, the Lower West Side of Buffalo, and document a particular ethnic/racial mélange in a particular neighborhood over a span of twenty and then thirty years (see Joanne Wypijewski’s contextual history in Triptychs). But, because of the power of the images and Rogovin’s respect for the inherent dignity of his subjects, they transcend the specificity of place.

Viewing Rogovin’s images may help students imagine how similar portraits and commentary could emerge from Jersey City or Utica or Youngstown or Detroit. Teaching with photography, particularly through the juxtaposition of images, opens space for an inquiry about presentation and representation, appropriation and documentation, whether the subject is cities, nations, or neighborhoods. For example, place August Sander’s portraits of German workers taken in pre-war Germany during the 1920s and early 1930s next to Rogovin’s triptychs and quartets. How does each photographer present individuals in their own social backgrounds? How do the images transcend typology? Rogovin’s success lies in his (still under-theorized) aesthetics and sustained political commitment to engage a mutuality of seeing rather than a dominance of looking.

With Anne Rogovin—his wife, muse, and conversational ice-breaker— Milton Rogovin earned a space in a place that was not his. They were welcomed and protected in the rough Lower West Side because they were not in the judgment, assessment, or policing business. They were not hunters stalking the exotic. Individuals posed themselves and in the hands of the Rogovins were not reduced to (non)employment or “ghetto” types. The subjects viewed the Rogovins too; one described them in 1974 as “a little old man and a little old lady taking pictures. I thought they were undercover [laughs]. Ever since then I’ve been knowing Milton” (The Forgotten Ones 90).

At times we’d work well into the night, walking into Buffalo’s ghetto, up a flight of dark stairs, through a hallway stinking of urine. Milton and Anne seemed completely oblivious to any hint of danger.Milton would set up his shot, snap a few frames on his Rolliflex and the interview would begin.

Consider these photographs as catalysts for future work in the classroom and community. They challenge facile assumptions about street or staged photography. They offer a visual and aural alternative to the urban center as decay without obscuring or omitting the realities of struggle and the scarcity of living-wage jobs.They answer the negation of Main Place rules with the affirmation of earned existence. Rogovin comments on the Triptychs:

“In 1972 when I started taking these photographs, I was still practicing optometry. My office was a few blocks from the Lower West Side, and I had a number of patients who offered to introduce me to their friends and relatives who lived in the neighborhood. Because I was aware of the many problems in the area, I decided from the beginning not to ask too many questions. As a result I do not know the names or addresses of the people I photographed. But I made sure that each person would eventually get a free print.

When I returned to the Lower West Side, first in the 1980s and again in the early 1990s, my big problem was to locate the individuals and families I had originally photographed. The easiest way was to take a box of photographs to the corner where there was the most activity. People would gather around and I’d show them the pictures. They would tell me who had OD’d, or was in jail; who had moved away, or had split up; and where I could find the others who continued to live there.

Sometimes a person is missing in the second or third photograph of the triptychs, or they were not available for reasons I’ve suggested. In a few cases the individuals had died sometime after I took the second photograph, so you see a blank space where the third photograph would have been. These photographs have no captions. I hope you will look carefully at them and provide your own captions. (Triptychs 37)”

Milton Rogovin returned for the last time to the Lower West Side in 2000-2002. With the help of photographers and filmmakers, Harvey Wang, Dave Isay, and David Miller of Sound Portraits Productions and the indefatigable Anne (who died in July 2003), he re-photographed “the forgotten ones,” extending the triptychs to quartets. Dave Isay describes this experience of working with the Rogovins as “magnificent… watching this tiny white-haired man and his wife striding past drug dealers with a smile and a wave on one corner, embraced with a ‘whoop’ and a bear hug by a group of burly, tattooed domino players on the next. His subjects—from cops to housewives to hustlers—would take one look at Milton and Anne, back again ten years later and greet them like long-lost family” (The Forgotten Ones 12-13).

Milton Rogovin bears witness to the thwarted and silenced in the tradition of Lewis Hine and Tillie Olsen. Neither he nor his subjects “forget.” His photographs will endure because they invite new generations to remember too and to see ever more fully. His book’s dedication to Buffalo’s Forgotten Ones “for their dignity, courage, resilience, and trust” aptly describes the life work of the Rogovins as well. Dave Isay further elaborates on witnessing the Rogovins at work: At times we’d work well into the night, walking into Buffalo’s ghetto, up a flight of dark stairs, through a hallway stinking of urine. Milton and Anne seemed completely oblivious to any hint of danger.Milton would set up his shot, snap a few frames on his Rolliflex and the interview would begin. At some point we’d pull out the old portraits—from thirty years ago, twenty, ten. It’s difficult to describe the intensity of emotions these photographs would unleash in their subjects. Most would just stare at them and then begin to sob. Milton would let out his soft,wondrous giggle, shaking his head slowly at the whole scene. Then the tears would start rolling down Anne’s face. She’d tug at his shirt and whisper, “Rogovin! Rogovin! Can you believe this? Rogovin!” And now he’s crying too, wiping his eyes, patting her arm. “Okay, Annie. Okay.” Then they’d turn to us, wanting to make sure we’d see what they’d seen, understood the importance of that moment. We had. (The Forgotten Ones 13)

ASX CHANNEL: MILTON ROGOVIN

All images © copyright the photographer and/or publisher