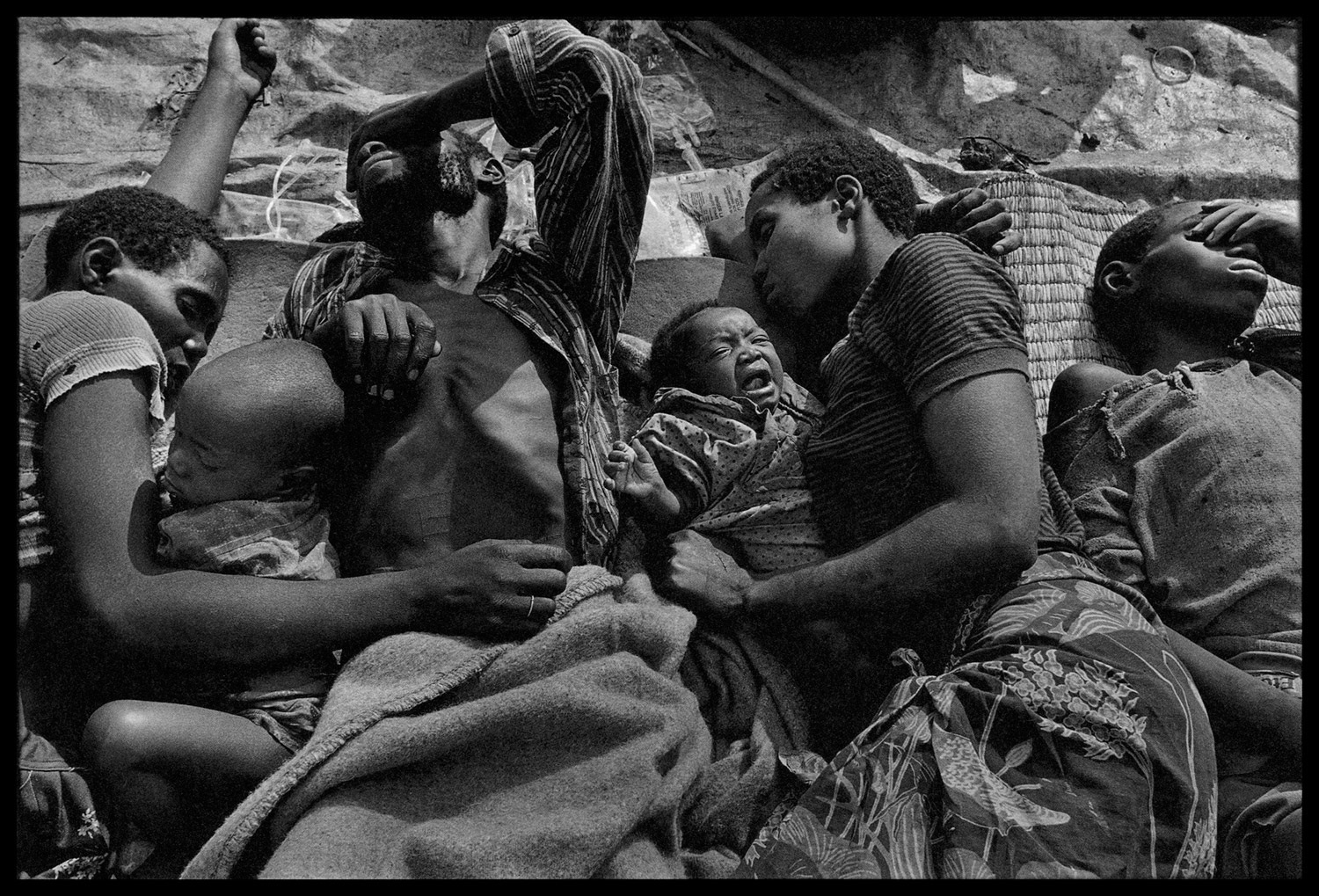

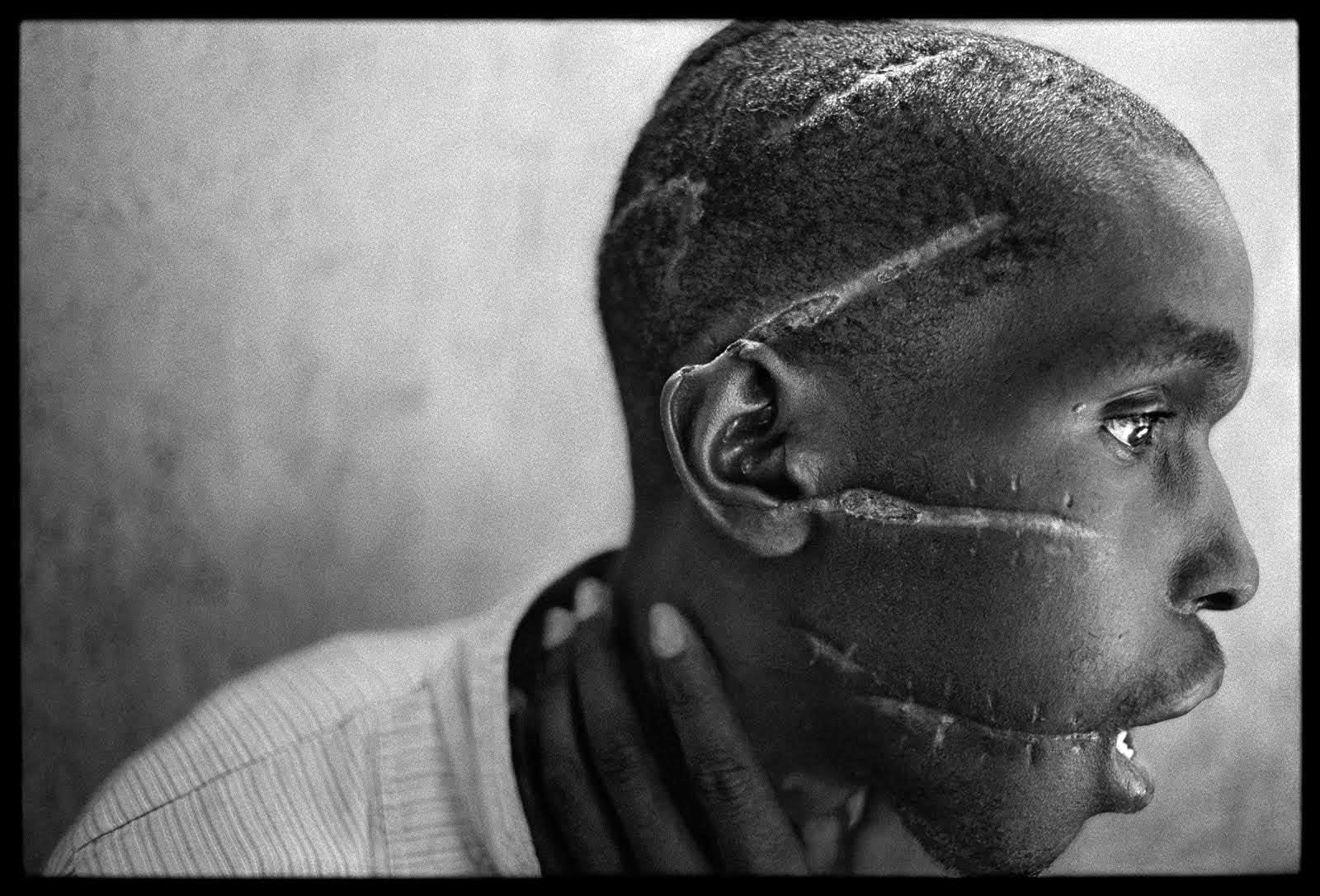

Rwanda, 1994

From its size to its content, Inferno feels like a cenotaph, a monument dedicated to the memory of the victims. These are not the victims of natural cataclysms, these are the victims of human greed for power, violence, stupidity, and of man’s destructive impulses.

By Bruno Chalifour, originally published in Afterimage, May 1, 2004

“Even in the age of television, still photography maintains a unique ability to grasp a moment out of the chaos of history and to preserve it and hold it up to the light. It puts a human face on events that might otherwise become clouded in political abstractions and statistics. It gives a voice to people who otherwise would not have one. If journalism is the first draft of history, then photography is all the more difficult, because in capturing a moment you don’t get a second chance.

Hundreds of years from now, when our descendants are trying to understand the time in which we are living, photography will be a crucial part of the record. In the present tense, photography is critical in helping create an atmosphere in which change is possible, not only possible but inevitable. It does this by making an appeal to people’s best instincts: generosity, the ability to distinguish between right and wrong, the willingness to identify with others, the refusal to accept the unacceptable. In the long run, photography enters our collective consciousness, and more important, our collective conscience. It becomes an archive of visual memory, so that we learn from the past and apply its lessons to the future.”

– James Nachtwey

These were the words that James Nachtwey pronounced as his receiving speech at Tel Aviv University last year when he shared the Dan David Prize ($1,000,000) in the “Present” category with documentary film-maker Frederick Wiseman. The very first sentence of this statement alludes to what may be the challenge and the strength of the still image in the twenty first century: how it diverges from other visual media with which it competes for exposure and attention, and how for over 150 years it has completely changed the way history has been recorded and the way it will be perceived. Photographers such as Natchwey, from Riis to Hine and many others, have provided the human collective memory and mind, with invaluable information for the future understanding of our times. Before photography, only the memory of those who could afford chroniclers would survive. Along with the advent of photography, the very focus of historians shifted; from L’Ecole des Annales to various schools in sociology and anthropology, scholars turned to vernacular culture, and the study of “how the other halves live” around the world. The least that can be noted here is an obvious synergy. However, and in spite of its accomplishments, documentary photography has been heavily stigmatized lately by postmodern doubts and well-deserved criticisms as well as by our culture of “infotainment” (or “entertainmation”). “The news that is fit to print” may not always be the one that is fit to analyze and remember. There have been many examples, from The New York Times to The Sunday Times (1)–only to quote two of the most prestigious daily news providers–of news and images worthy of world attention that competed for the front page with fashion shows … and lost. The immediacy of television and video images, and our too easily passive fascination for the moving image, have deprived photojournalists (as well as “pen” journalists) of their traditional audiences. Moreover the recent concentration of image banks and image distribution networks has resulted in the disappearance (de facto even if their names still survive in some few cases) of numerous photo agencies (Viva, Sygma, Sipa, Gamma, etc….) and the firing of scores of photographers. If the twentieth century saw a paradigmal shift, it is probably in the way that control moved from the word to the image. From the individual, to the corporate world, and even public spheres, everyone wants to control not only their own images but any image that could be used as evidence against any of their flaws or wrong doings. From Corbis to Getty or Hachette, a few private enterprises have made it their goal to hold the visual memory of the planet, and to control the distribution of visual information. In controlling the distribution of images they end up controlling their content. Only the ones that “fit” the definition of the content that is appropriate are distributed. The notion of “appropriate” can be greatly affected by what is “commercially correct.” And the market has its reasons that do not always follow reason.

Some fifty years ago, a group of five reporters, who had photographed on the same front during the Spanish Civil war and WW II decided to take control of their own destinies and productions. From this idea “Magnum” was born in 1947. It still survives and its members are still among the elite of the profession although a few of them have been expressing reservations about decisions taken in the recent past concerning either the work produced by some new members, or the recycling of the prestigious archives in exhibitions, books, postcards and posters–a strategy that allows some financial gain but that undercuts the celebrated in-depth approach of the agency, often showing images outside of the context in which they were taken or they were supposed to be shown. It is a truism to say that a photograph without a caption is to a new audience what a blind person without a dog can be in an unfamiliar space. Documentary photographs shown in sequences or series “make more sense” and can exist without accompanying text. Deprived of context, they rely on a caption that often fails them, especially in the context of purely commercial ventures, they just end up participating in a vast world of visual entertainment and lose impact, meaning, and relevance.

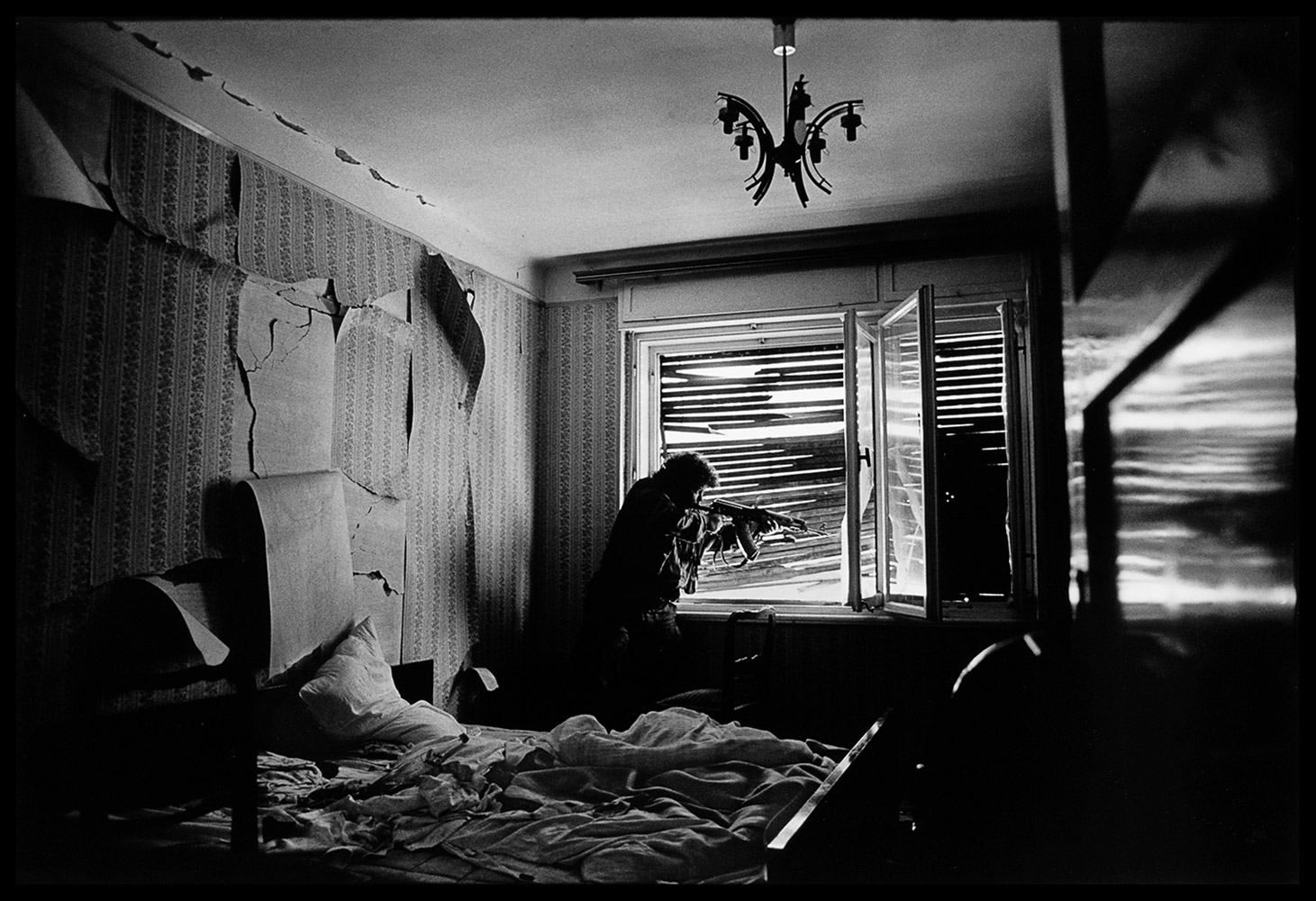

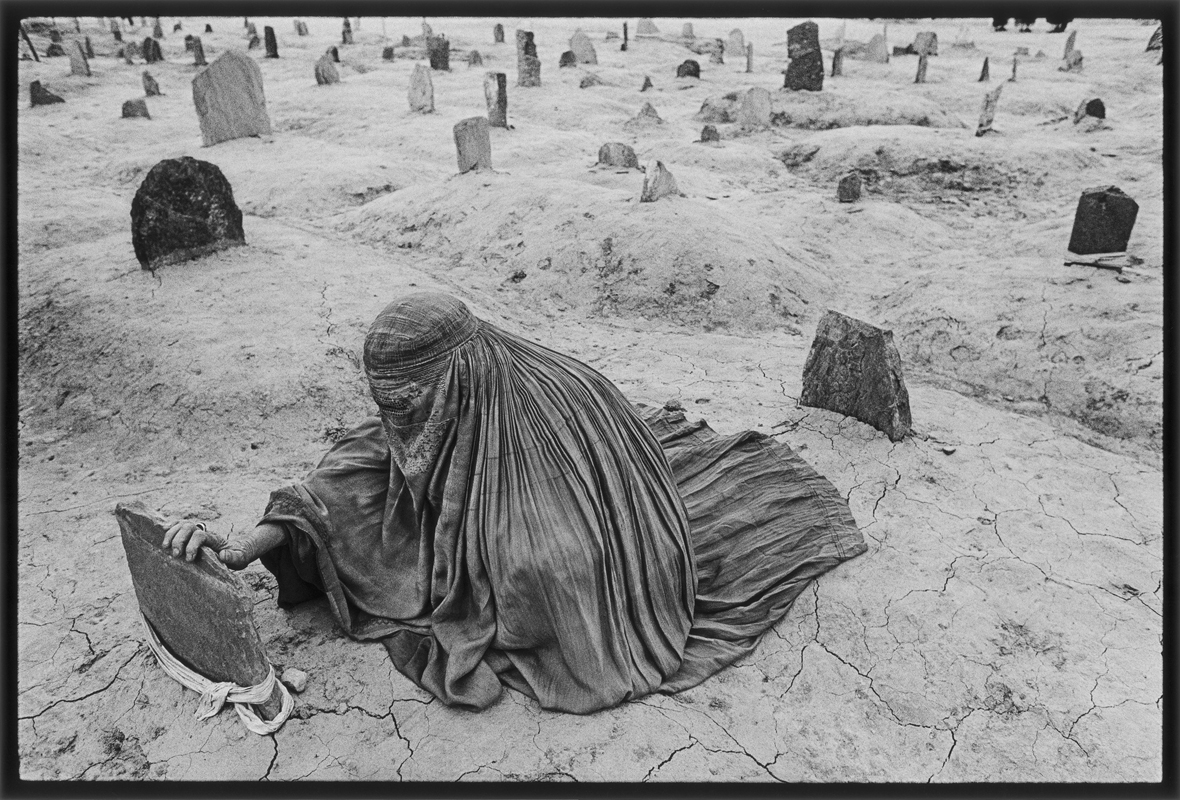

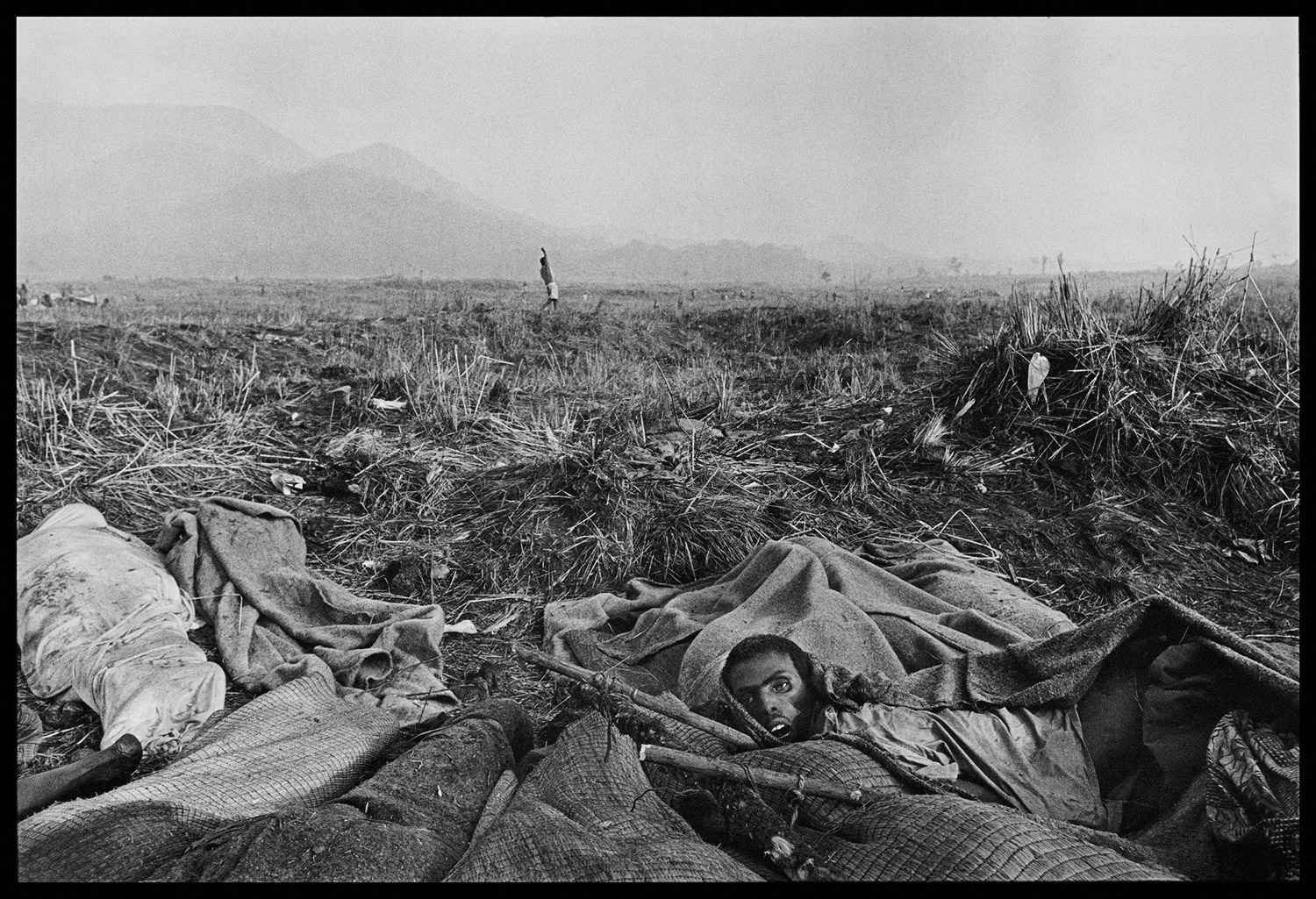

In the late 1990s, one man who had been a member of Magnum for a few years as well as a long-time war correspondent for Time magazine, decided to create a different stage for his work. For years he had been documenting conflicts around the globe, and the dire consequences that affect local populations. What “progress” in technology, and the use of the military to expand markets and control resources, have brought to war is the fact that since WW II, the number of civilian casualties has largely exceeded that of personnel dying in uniform. More than ever the ones declaring war are the last and least to participate in them. In the distant past, the warlords used to lead their troops to the battle-field, and stay there with them; now they see the impact of radio-active radio-guided missiles from their bunkers. Famine and lack of medicine are WMDs (weapons of mass destruction) that are far more efficient than the “real” ones; logically, they always affect civilian populations, and among them those who are the most vulnerable and the least involved in the conflict: children, elderly people, and women. After witnessing so much pain and injustice, in what looked very much like an effort to fight helplessness, and disgust, and protect himself against a cynicism that would have meant the end of his career as a respected war photographer, James Natchwey edited his black and white images for a very black book. Inferno, published in 1999, summarized ten years of photographic work around the world, from Romania to Somalia, India, Sudan, Bosnia, Rwanda, Zaire, Chechnya, and Kosovo: ten years of the worst of human nightmares prefaced by a quote from Dante’s Divine Comedy: Inferno.

Rwanda, 1994

Afghanistan, 1996

“I want my work to become a part of our visual history, to enter our collective memory and our collective conscience” – (James Nachtwey, Inferno, 471).

Published by Phaidon, the book is more than a traditional coffee-table book, it weighs as much as a coffee-table, a book difficult to toss away. With the past 5 years of conflict in Europe and the Middle East (former Yugoslavia, Chechnya, Israel, Afghanistan, and Iraq), the devastating civil wars in Africa, 9/11/2001 and the second war in Iraq, books presenting photographs of war have become a common sight in stores. The available technology (satellite communications, digital cameras) allows a fast distribution of images, almost in real time–which can easily be achieved with video and TV crews–however a book in the shape, size and content of Inferno is still possible. Why is it? Why were these images not published, or at least not given enough exposure, to the point that a book of this magnitude came to life? Why do a photographer and a publisher/distributor take the financial risk of publishing such a book? Is this book an attempt to counter the homogenization of the media, to make a statement? If a statement, what statement?

From its size to its content, Inferno feels like a cenotaph, a monument dedicated to the memory of the victims. These are not the victims of natural cataclysms, these are the victims of human greed for power, violence, stupidity, and of man’s destructive impulses. We are our own nightmare even if we pretend to ignore it, even if we close our eyes on the fact that some are paying a high price for our hyper-consumerist society. We pretend to export progress, ideals, benevolence, when in fact we export far more violence, destruction, and hatred. We pretend to be the champions of good while we generate evil (Brecht’s “beast”) and breed it. But we want to believe in myths that cannot explain how the “Freedom Fighters” of yore became the Talibans of today, how the ally we helped financially and militarily, turning a blind eye when he used chemical weapons against Kurdish populations, became the tyrant of “the axis of evil” In Inferno, Natchwey, rather than pointing at the perpetrators, shows the victims because he knows that while the perpetrators might be made accountable, such strategies only target a few scapegoats, whereas the participants in his photographs keep on suffering and dying. Inferno sounded like a cry; its impact was dubious, because of its cost and its lack of practical qualities. On a formal level, double-spreads are probably not the way to show photographs that they fragment, distracting the viewers’ attention. Although it can be argued that this fragmentation plays a role in the deestheticization of photographs depicting “the pain of others”, an answer to the common reproach that the esthetic value of such photographs can be obscene, can distract from their content. As Natchwey mentioned in his receiving speech in Tel Aviv, Inferno was meant as a historical document, as impracticable and a bulky as a WW I memorial. However, the statue that were molded in the 1920s did not stop Hitler or Mussolini, they did not prevent Guernica either. Going back to Guernica: without Picasso’s work who would know of that small Basque village? Didn’t Franco die in his bed?

The human psyche needs myths and legends to titillate its imagination, and define its identity. There is no better myth or legend than one that starts in tragedy, and ends with it. Human histories, from any corner of the planet, have been written with such tools. History can be nothing but dull, sometimes dumb facts. A thousand words, thence a photograph, cannot explain history but they can make a good story. While Nachtwey has embarked on his historical mission, others around him are working at giving it strength, building his myth. In the past five years, first with Inferno then with Christian Frei’s War Photographer (2), Natchwey’s legend has been growing, giving more weight to his statements because of their increased audience. In War Photographer, in a very sullen and solemn voice, Nachtwey reads a credo that he wrote in 1985:

“Is it possible to put an end to a form of human behavior which has existed throughout history by means of photography? The proportions of that notion seem ridiculously out of balance. Yet, that very idea has motivated me.

For me, the strength of photography lies in its ability to evoke a sense of humanity. If war is an attempt to negate humanity, then photography can be perceived as the opposite of war and if it is used well it can be a powerful ingredient in the antidote to war.

In a way, if an individual assumes the risk of placing himself in the middle of a war in order to communicate to the rest of the world what is happening, he is trying to negotiate for peace. Perhaps that is the reason why those in charge of perpetuating a war do not like to have photographers around.”

[In the field what you experience is extremely immediate. What you see is not an image on a page in a magazine 10,000 miles away with an advertising for Rollex watches on the next page. What you see is unmedicated pain, injustice, and misery.]

[This passage of the original text was not included in War Photographer.]

“It has occurred to me that if everyone could be there just once to see for themselves what white phosphorous does to the face of a child, or what unspeakable pain is caused by the impact of a single bullet, or how a jagged piece of shrapnel can rip someone’s leg off–if everyone could be there to see for themselves the fear and the grief, just one time, then they would understand that nothing is worth letting things get to the point where that happens to even one person, let alone thousands.

But everyone cannot be there, and that is why photographers go there, to show them, to reach out and grab them and make them stop what they are doing and pay attention to what is going on, to create pictures powerful enough to overcome the diluting effects of the mass media and shake people out of their indifference, to protest, and by the strength of that protest to make others protest.”

Nicaragua, 1984: Relic of civil war became a monument in a park. @ James Nachtwey

Whereas Inferno was entirely in black and white, which reinforced the solemnity of its tone and stance, 95% of War is in color, a sign of the times and of the market. The media want color.

With War: USA, Afghanistan, Iraq, a book and catalogue composed of the photographs by members of VII (the photo agency whose founders are all photographers, Nachtwey being one of them) the reader holds the physical heir of Inferno: same size, same weight. But in fact, a gap lies between the two. Whereas Inferno was entirely in black and white, which reinforced the solemnity of its tone and stance, 95% of War is in color, a sign of the times and of the market. The media want color. All the photographs were taken by members of VII (whose number now exceeds the original seven founders). All images are “fit to print” although the ones that Gary Knight took evoke a reality that was denied to the war in Iraq for some time (paradoxically, we seem to have better information, and a better idea of that war and its victims since it supposedly ended). After an extremely close encounter with the collapse of the Twin Towers, Nachtwey seems to have lost some of his philosophical detachment as expressed in these words ending his statement: “On September 11, history crystallized and I comprehended that I had actually been photographing different phases of the same story for over twenty years, the conflict between two worlds, between two value systems. Islam and the West.” In times of flag-waving, this ambiguous sentence will probably help the diffusion of the book and the health of the agency. However it seems strange that a man, a quasi-legend, described in Frei’s documentary as a lone philosopher and humanist, should suddenly fall for a Manichean description of the world, one that focuses on religious exceptions to turn them into bad generalization.

9/11 produced a very obvious change in the rhetoric used to describe the relationship of some with the Middle East. These have been times when some chose to make us jump a few centuries back and use the same arguments for a holy war as those they were denouncing. Both they and Nachtwey (on a very different level though) in his unfortunate statement advocate anti-humanistic approaches to the current situation, anti-humanistic because based on exclusion. One should not suspect the photographer of any violent intentions. The ambiguity of his statement remains and opens the doors to various interpretations, some of which could be seen as dangerous. “Humanism remains the last wall against barbarism,” wrote Edward Said in an essay published by Le Monde Diplomatique last year. There are risks in renouncing humanism and embracing a market strategy and its value system for which a human life only costs so much. The imagery in War has a tendency to evoke a well-known magazine by the rather “safe” distance it keeps with the events that it colorfully depicts. Once the book closed, what did we learn, what do we understand?

Footnotes:

1 — See Colin Jacobson’s book. Underexposed, (VisionOnPublishing, 2001) for more examples around the world.

2 — War Photographer, a 96-minutes’ documentary on Natchwey by Christian Frei (2001) has won several awards. The director followed Natchwey around the globe for a whole year. Some of the footing was shot with a digital minicam placed on top of Natchwey’s camera and allowing the audience to see exactly what the photographer saw as well as the exact moment when his index pressed the shutter-release.

(All rights reserved. Text @ Bruno Chalifour, Images @ James Nachtwey)