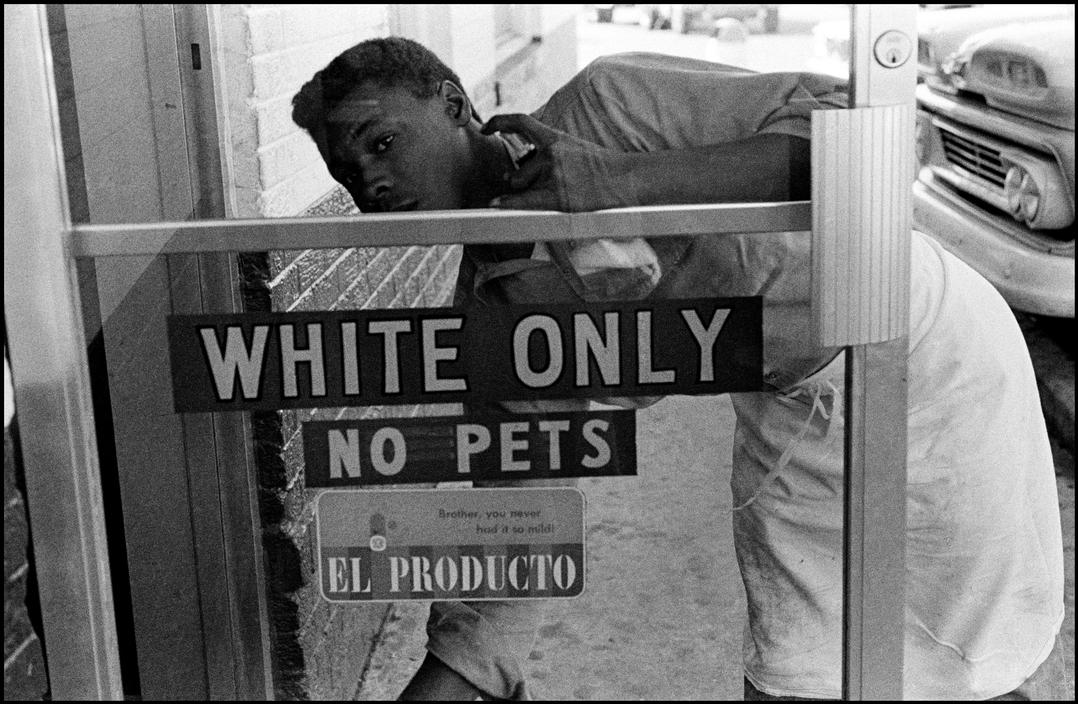

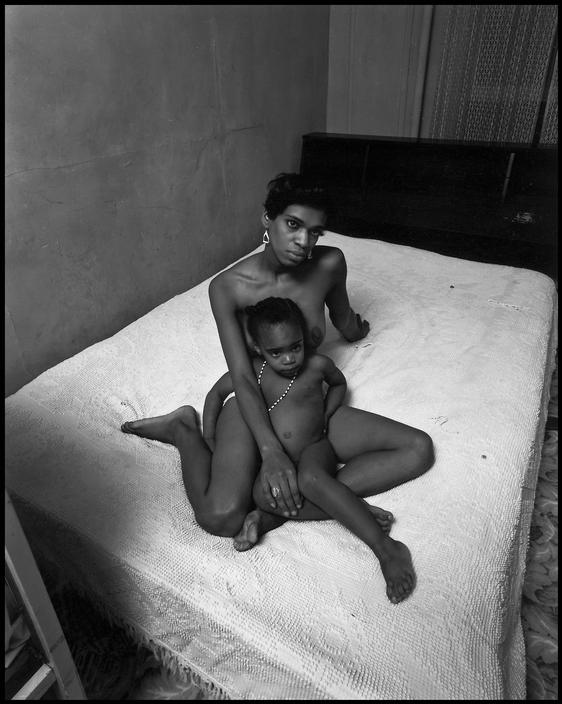

USA. Hampton, Virginia. 1962. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

“Look, I’m kind of an explorer. I’m entering a world and it takes time.”

A Magnum photographer, Bruce Davidson has been renowned since the late fifties for his photographs of gangs in Brooklyn, and subsequent projects including New York’s East 100th street, circus performers, civil rights marchers and the bad old days of the New York City subway, as well as a large, distinguished body of editorial work.

I went to visit Bruce Davidson on a painfully cold February morning. His wife, Emily, let me into their large Upper West Side apartment, which overflows with more than forty years of sculptures, art, prints of Davidson’s work and family photos. I asked Bruce questions about his life in photography and he showed me his darkroom and fifty years worth negatives and prints. The following is a slightly edited and condensed account of that conversation.

Owen Campbell: Early in your career you made a lot of studies of groups of people, the Yale football team, the gangs in Brooklyn, East 100th street – So my question is how do you as an outsider put yourself into the group in a way that gives you access?

Bruce Davidson: You have to take it a project at a time. With the football team, I was a student so I got an appointment with the coach. And I walked into his office because I wanted to get permission to photograph along the bench, where the players were waiting to get into the game. As soon as he saw me he lifted his eye up from his desk and said, “Son, you’re too small for Yale football.” I said I’m not here as an athlete I’m here as a photographer and I’d like to have permission to photograph in the locker room, whether it’s tense or they look beaten up, or whatever.

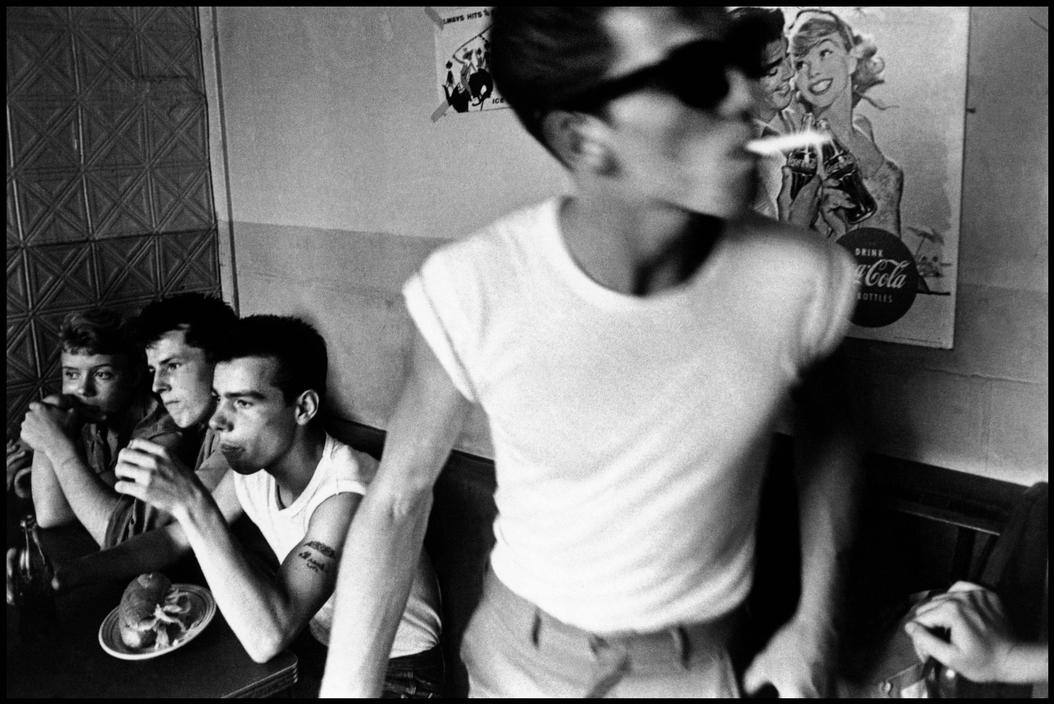

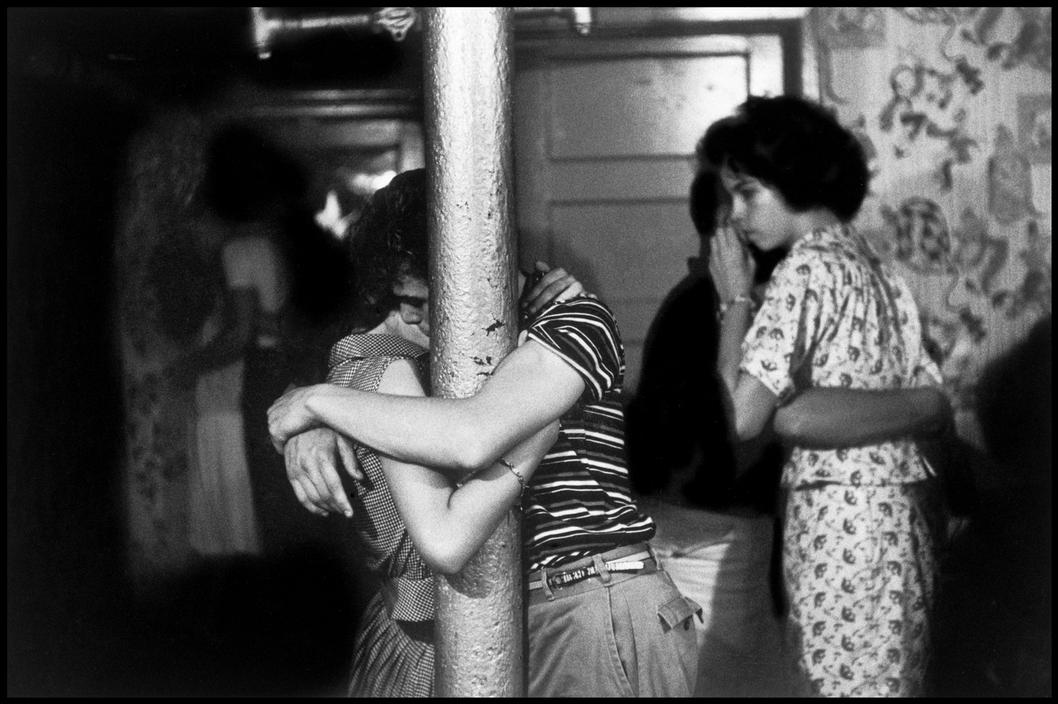

USA. New York City. 1959. Brooklyn Gang. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

USA. New York City. 1959. Brooklyn Gang. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

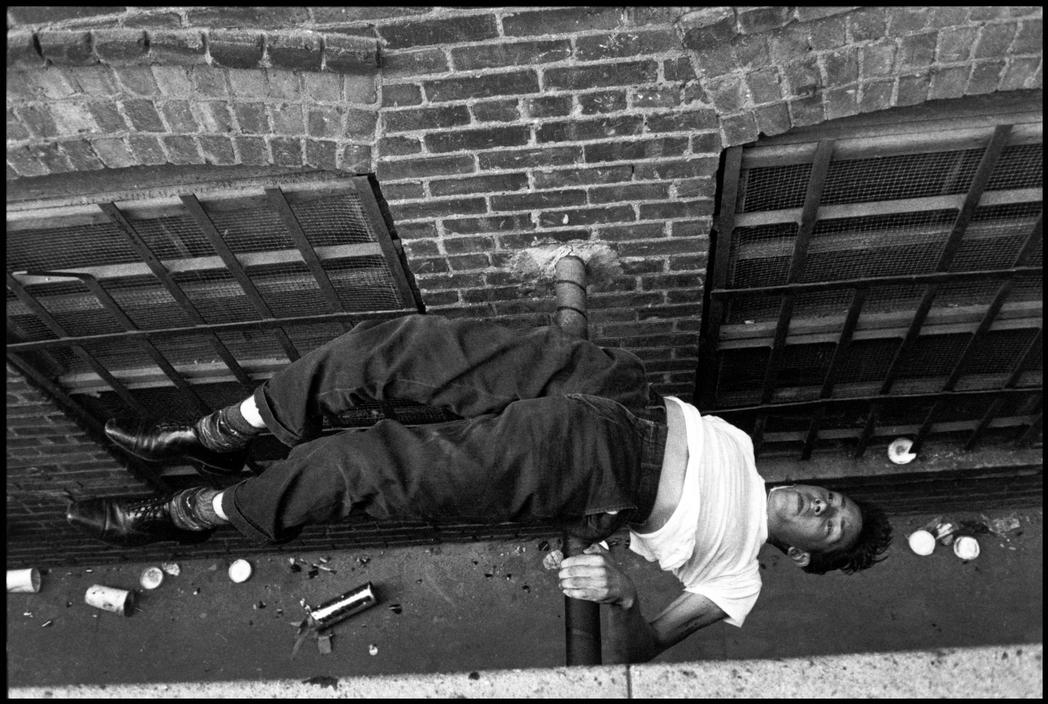

USA. New York City. 1959. Brooklyn Gang. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

“The problem is that, you’ve got to stay around for a while; you’ve got to earn your dues.”

I understood all that because I was a football player in high school, and scared to death that the coach might call me in. Anyway, [the football series] was about tension. I just hung out. I never saw a game because my back was always to the field but I could feel the wind blowing by me. But I didn’t know these people; I just knew their form.

OC: Would you say that’s true about most of the groups you photograph: you don’t know the people you just know the form?

BD: Look, I’m kind of an explorer. I’m entering a world and it takes time. Young kids, students, they want it too quickly. They should take one thing and really explore it, look at from different angles. With the Brooklyn gangs, I’d read about them, they’d made the front page of something, and I went there and offered to take pictures of their bandages for their lawyers. And the first pictures were made on Kodachrome so I just gave them the slide. That was the beginning; I was coming every once in a while, weekends, no agenda. They were always hanging out, sometimes in Prospect Park, sometimes just around the candy store. After a while I became them. I’m not violent, but I could feel their depression, their abandonment, that there’s nothing for them there. I didn’t know at the time how poor they really were. But years later, many years later, the leader of the gang called us here (at the apartment) and my wife, Emily, insisted on going with me to meet him, the leader of the gang, after forty years.

It turns out she spent the next ten years on Saturdays recording his life and produced a book. The book is interesting because it’s about that poverty, it’s about alcoholism, it’s about his life and drugs and crime and then the way back. And now he’s in his seventies and he’s a retired drug counselor. At one point he was treating some of the members of the gang who were seventy-five years old and still on heroin. Her book dovetails very beautifully into my innocence. He once described his mother to Emily, and she was quite a powerful woman, she had seven children, alcoholic husband and she was a drunk also, and as he described his mother, I said “there’s a picture of a woman in my contact sheet who looks like her,” and I printed it for him and he said, “There. That’s my mother.” There were a lot of things that were coming together, in the new book and the new experience. I wouldn’t have known that woman was the mother of the leader, but Emily found that out. So that is the way I work.

OC: When you take photographs of people who are from a different place, poverty, do you as a photographer feel a debt to that person who through their misfortune creates a good photograph?

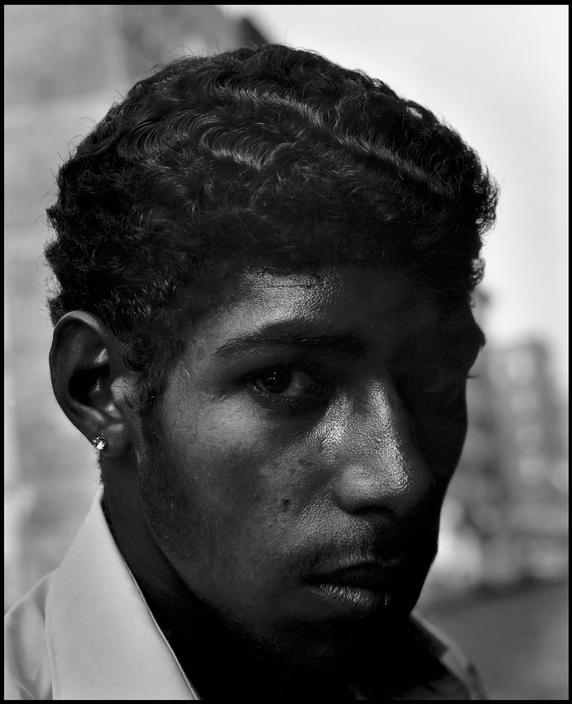

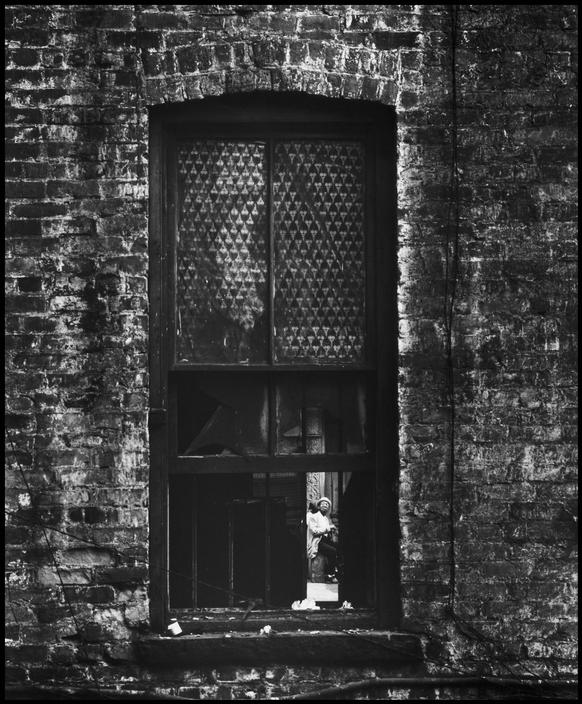

BD: The problem is that, you’ve got to stay around for a while; you’ve got to earn your dues. Poverty is kind of sexy, poverty is photographic, it’s what photographers look for. In the case of East 100th street, I had an entrée, the picture librarian at magnum photos, Sam Holmes, had a cousin who was a white minister living and raising his children in Spanish Harlem, so I was introduced to him. But he said he couldn’t give me permission to take pictures here, you have to appear in front of the citizens committee and they will either say yes or no. So I did, I presented myself and they said, “we have photographers coming through here all the time because we’re poor, and that’s very photogenic to them but they come and they go and we never see the pictures and we never see anything change.” I said I work a little differently, I work eye-to-eye, I have a large-format camera where I need quiet and things to settle down and I need to be there because I have this heavy camera and a tripod and a strobe, and I will give prints to people. They said they would try me out and I said, if you can find a family of ten, I’ll photograph them as an example of my work, and I did. It took three weeks because I’d arrive on a Sunday but there would only be eight. I had to come a couple of times before they really got all their family together. So that was really the beginning where I was really in the picture myself, with the cable release on the camera and the eye to eye relationship, and I would bring back prints and give the prints to the people. That took two years; it sustained me for two years. And that’s basically how I work; I just keep going back and back.

USA. New York City. 1966. East 100th Street. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

USA. New York City. 1966. East 100th Street. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

USA. New York City. 1966. East 100th Street. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

“I presented myself and they said, ‘we have photographers coming through here all the time because we’re poor, and that’s very photogenic to them but they come and they go and we never see the pictures and we never see anything change.'”

OC: But in a different scenario, like the subway, where you’re interactions are more fleeting and you’re also shooting with a strobe…?

Yes, because that would show people there was something going on. And when people would ask me what I was doing I would say I was doing a book on the subway, its about time someone did; because at that time the subway was full of graffiti, it wasn’t run very well and it was dangerous at night. That was an exploration in black and white to begin with, but then I transferred over to color because there was a dimension of meaning to look for color in a place that wasn’t colorful – but it was colorful because the graffiti gave a dimension of meaning that it wouldn’t have had if I’d just stuck to black and white. The black and white photographs are equally as good as the color ones, but they’re different.

OC: Do you find people were ever felt offended by the flash or invaded on the subway? There’s the photo of a very strong man with no shirt and a chain around his chest, and the way the photo is framed it seems he’s looming over you. It’s a very intimidating photo.

BD: You see you have to factor in the mood. These were people coming back from sunning themselves, they’re almost red-hot, there’s iridescence to their skin color. I always work very close, so I’m less than a meter away, half a meter from him with a wide-angle lens. And I might have said, “You got a great tan there, man” so the mood was right. Coming back from the beach, they had a few beers, they’re at ease.

I got his name, at least I think I did, but I lost track of him. Years later, I was reintroduced to him, I was showing slides at the 92nd street YMCA and he came up to me and said I’m the guy. I asked what he did now and he said, “I’m a bodybuilder and a trainer”. He suggested I could use a little of his expertise. I didn’t take him up on that but some day I might.

OC: Do you ever find that as you gained more of a reputation as a photographer that it changed the way your subjects presented themselves to you?

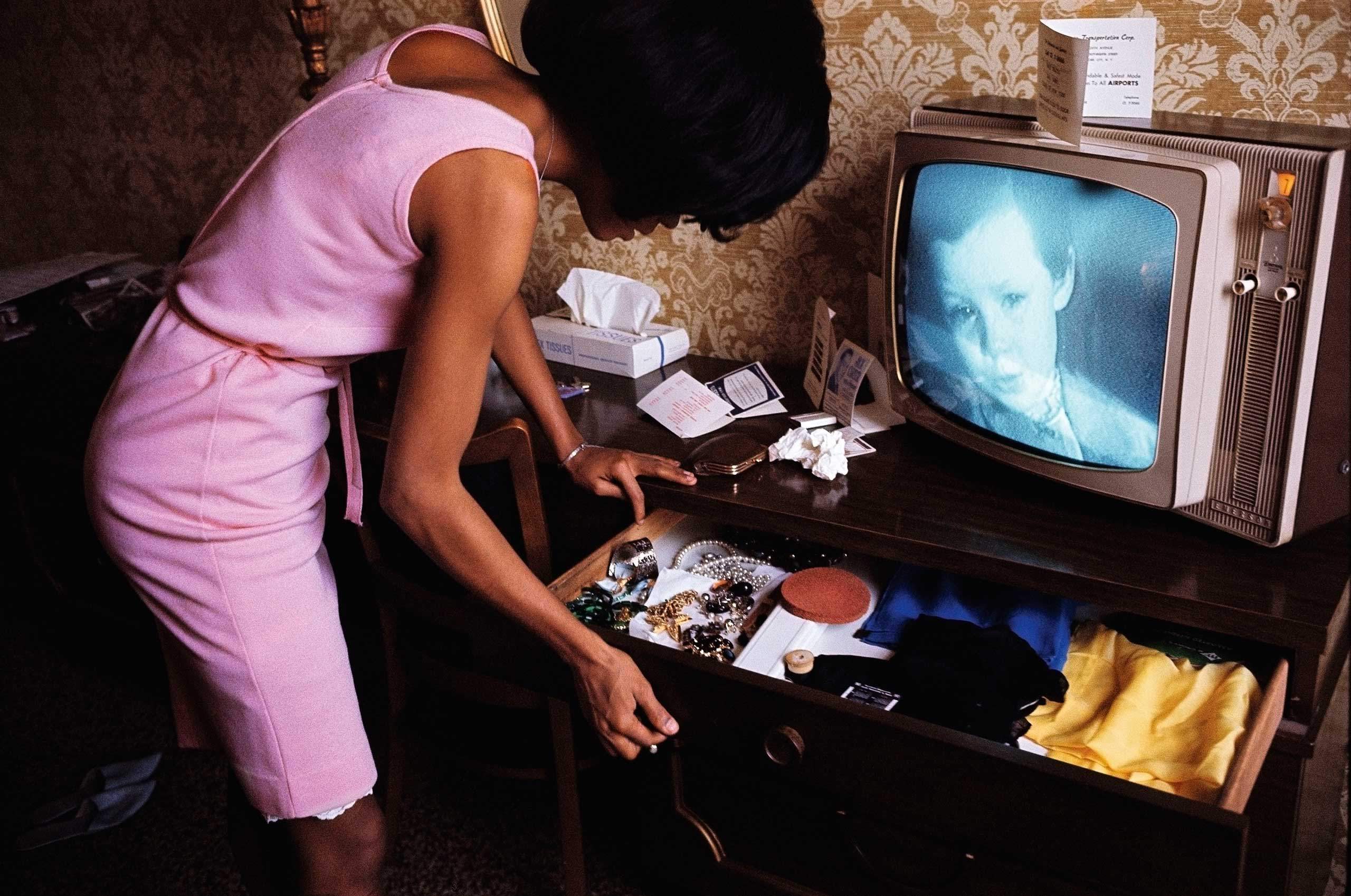

BD: Well it depends on who and what specifically. For a while I was photographing a lot of Hollywood movie stars, and there, at that time, actors would need to have that publicity, it would usually be written into their contracts, that they would need to spend so much time being interviewed and blah blah blah, Most of it was kind of interesting and fun to meet these people through my camera, up to a point. Later on it got a little bit annoying because there was hair and make-up and it wasn’t free anymore, there was more of a commercial feeling to it.

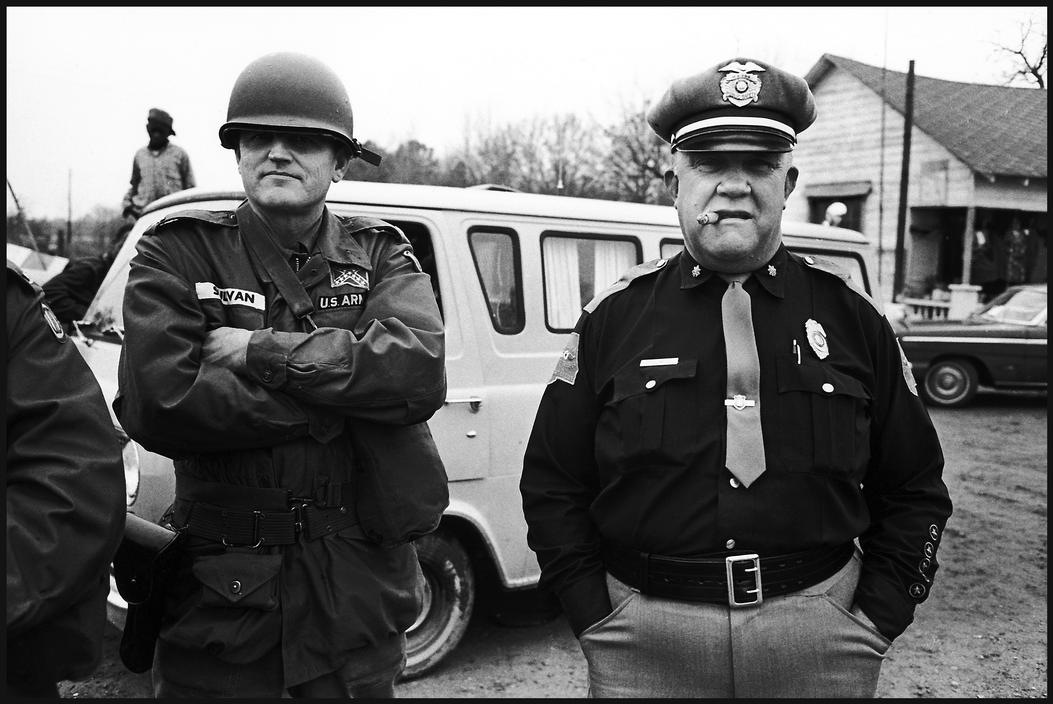

USA.Alabama.1965. The Police and the Army escort the Selma Freedom Marcher led by martin Luther King. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

USA. Birmingham, Alabama. 1963. Firemen turn their hoses on civil right protestors. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

“Because everything you do is political, you can’t avoid it.”

OC: You took famous photos of 1960’s the civil rights movement. Were you sent down there as a photojournalist?

BD: I was a white guy from the Midwest; I didn’t know anything about black culture. But I had applied to a Guggenheim fellowship to photograph youth in America and I received the grant. At the same time someone said to me that there was a group of college students protesting segregation laws and I thought, “Well, that would be interesting.” So I went down there. That was the freedom rides in 1961 and that made me aware of the plight of people that I really didn’t know, so I started photographing Birmingham in ’63 and the Selma march and a number of things over a period of five years that I encountered and sensitized me.

OC: Do you think it would be fair to say the pictures you created there were in themself a form of political activism?

BD: Oh they were. Because everything you do is political, you can’t avoid it. It’s not only political; it’s innocent, there has to be a kind of meaning and understanding of that, too. I wouldn’t say to myself, I’m going to be sensitized today, I just went down there to document and capture what was really going on. And those photographs still come alive.

I went back down twenty or thirty years later. I photographed in 1965 a woman in a sharecropper’s cabin holding a young child. Thirty years later I found that child and I photographed her. She was now an insurance agent, still living in the same area but no longer poor. I photographed almost everyone in her family, so that brought things back into focus. And that’s important for photographers to be able to do, too, to go back and be able to see what’s going on. There are photographers who do and I was one of them at that time.

OC: Earlier you did studies of groups of people, and later you seemed to be more interested in landscapes. Is that accurate and would you say there’s something within you that’s motivating that change?

BD: I think you could say all my work is a landscape, a landscape of understanding. I don’t differentiate, I don’t say this is a landscape, this is a portrait – it could be a portrait of the foothills that relate to the grid of Los Angeles. There could be both beauty and the city at the same time from the foothills. Do you know Los Angeles at all?

OC: Very little.

BD: That’s something I wanted to explore, because LA is in a bowl surrounded by the foothills of the San Gabriel mountains. The Hollywood sign interested me because it’s a cliché, everyone wants to get their sign taken in front of the Hollywood sign, but no one had ever explored the back of it, what the sign sees. What the sign sees is a desert and a real rough landscape. You can’t walk through it very well, I had an assistant and in order to get to the angle I needed we had to repel on a rope. It wasn’t real big, it was more like holding on to a rope while going down a steep hill but it was crumbly, so he would carry my stuff down and then he would coax me down.

OC: And you were in your seventies at this point?

BD: Oh yes, very much in my upper seventies, so that was a lot of fun. The total thing was a lot of fun.

I had this hotel that had a full kitchen and big closets and I decided to stay there because we could make a darkroom out of the closet. We brought rubberized black cloth and the whole bedroom closet became a darkroom, because I had to load and reload my film day after day. So that was fun because that was very primitive, shooting 4×5 Linhof. And the pictures that came out of that were strong. You call them landscapes but they’re cityscapes.

OC: What lead you to want to do this project?

BD: I wanted to do it for a long time. I knew that in my 1964 encounter with Los Angeles, which was an esquire assignment, that I hated the place. It was full of pollution; you had to have a car. I felt the people were almost like mannequins. I was a little bit angry myself at that time, it was a perfect fit: the anger that was implicit in Los Angeles and the anger within my own body and mind meshed and I took a really strong body of nasty pictures. When I gave them to esquire they rejected them, [the pictures] were too hip for Esquire at that time. It was more appropriate for the Beastie Boys, who actually did acquire some of that work.

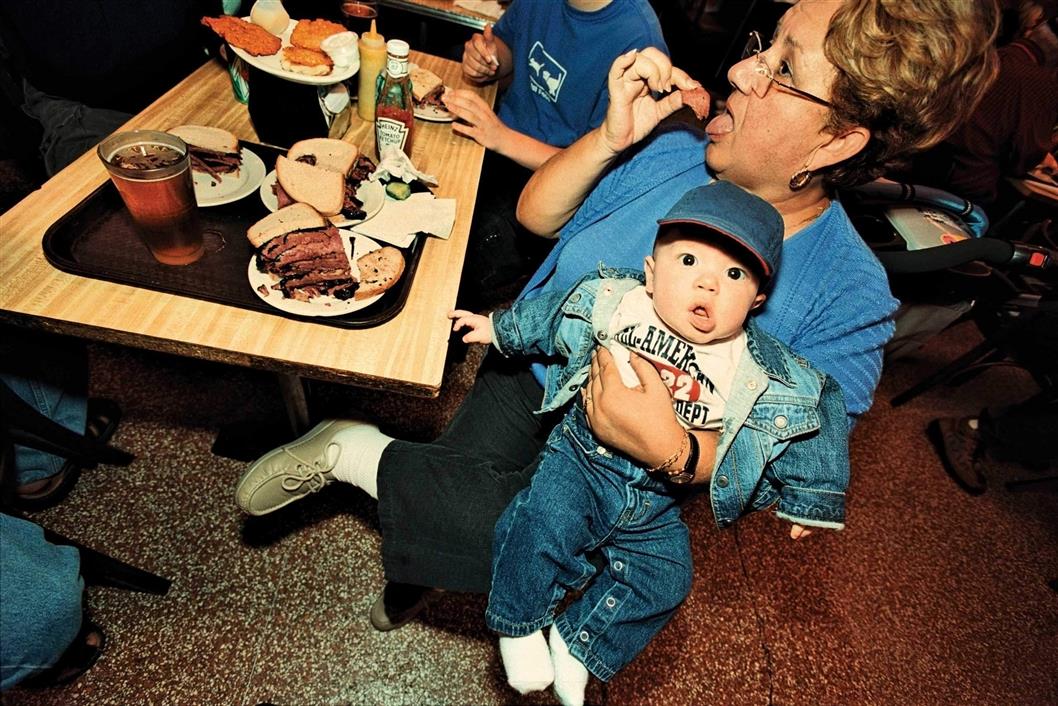

USA. New York City. 2004. Katz’s Delicatessen. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos/Steidl

USA. New York City. 1965. Diana Ross in a hotel room at the Apollo. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos/Steidl

Great Britain. Wales. 1965. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos/Steidl

OC: You’re feelings have maybe changed about LA?

BD: LA has cleaned up its act a lot and I’ve come to more of a peaceful place. I’ve come to a place where I can find beauty even in Los Angeles.

OC: You’ve taken a lot of photographs in New York City, which has been you home for many years. Is it different to take photos in a place that’s your home versus the photographs you take when you’re traveling, in Mexico, LA or India?

BD: Wherever I find my camera, it’s sacred to me that I observe and reflect, even in a personal way, with my subject. I think that I’ve been true to that, because those photographs sometimes come back to you, like that sharecropper woman. I felt I was true to that photograph and later on the child in the photograph grew and that photograph became a very historical document for her. It was taken just as the Voting Rights Act was adopted, and then she could get a good education, as could her children.

OC: You told me before that you don’t have an iPhone, so obviously you don’t take photos with one. But do you feel that those sorts of photos are less valuable?

BD: It’s different. Everyone has one of those phones and they’re taking pictures of everything. And I take pictures, too, of the same thing everyone else is taking pictures of, but mine are a little different. They come from a different place.

I go down the street when the weather gets nice, I might have a digital camera, but my approach would be the same.

OC: Most of the images I see in my daily life are on my phone. I guess that’s not a thing for you if you don’t use a smartphone.

BD: My true love is silver gelatin. My history in photography, which spans over fifty years, it is all basically silver gelatin. In my imagination there’s nothing more beautiful than a beautifully printed 11×14 print on good paper. Now the paper quality is diminished but we find a way of making it almost as good as it could have been with a lot of silver.

Up until recently I’ve printed most of all my work. Up until my Los Angeles photographs (2008-2013) I made the master set, and we have a very good custom printer who works off that for acquisitions. I don’t have time any more to make prints for sale; other people have to do that for me.

My motive is to go on, and going on I may even need new technology. I’m working in an area right now where there isn’t a black and white film sensitive enough. My digital camera is much more sensitive than my eye. Sometimes I take pictures in places where I can’t see and yet it prints beautifully. So things change, and that worries me because I still have a darkroom here. I haven’t printed in a long time, but I could. I’m set up. So I go back and forth, but my true heartthrob is black and white silver gelatin.

OC: What is the project you’re working on?

BD: I’m not sure if I should really talk about it at this point. It’s too new. It’s enough to say that I’m working with a digital camera and I’m very happy with the results I’m getting.

Published by Steidl

Edited by Bruce Davidson, Amina Lakhaney. Text by Bruce Davidson.

Owen Campbell is an an artist and writer from Wilkinsburg, PA.

FOLLOW on Twitter @OwynnKampbell

Bruce Davidson on Magnum Photos

EXPLORE ALL BRUCE DAVIDSON ON ASX

(All rights reserved. Text @ Owen Campbell. Images @ Bruce Davidson and courtesy @Magnum Photos.)